Federal Reserve Economic Data: Your trusted data source since 1991

Data in this graph are copyrighted. Please review the copyright information in the series notes before sharing.

NOTES

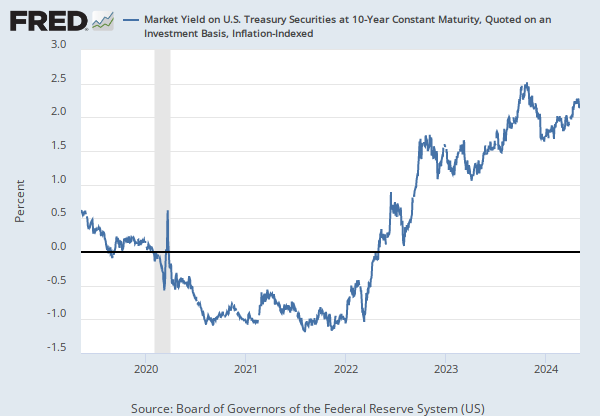

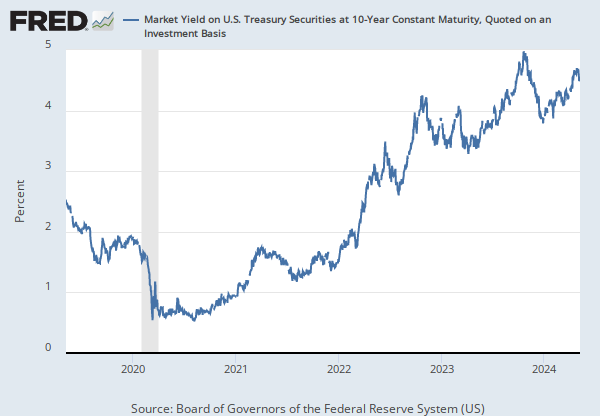

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

Release: H.15 Selected Interest Rates

Units: Percent, Not Seasonally Adjusted

Frequency: Daily

Notes:

For further information regarding treasury constant maturity data, please refer to the H.15 Statistical Release notes and Treasury Yield Curve Methodology.

Suggested Citation:

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Market Yield on U.S. Treasury Securities at 10-Year Constant Maturity, Quoted on an Investment Basis [DGS10], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS10, April 12, 2024.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

Release: H.15 Selected Interest Rates

Units: Percent, Not Seasonally Adjusted

Frequency: Daily, 7-Day

Notes:

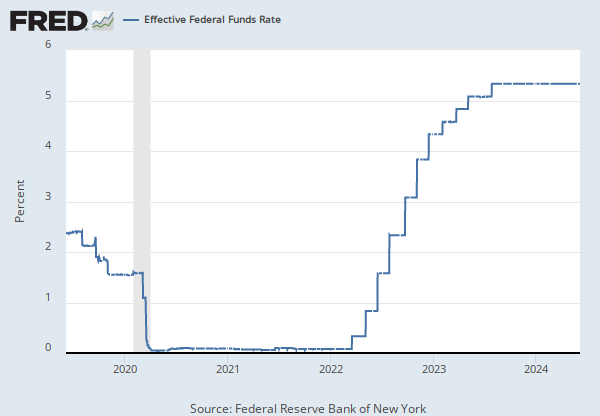

For additional historical federal funds rate data, please see Daily Federal Funds Rate from 1928-1954.

The federal funds rate is the interest rate at which depository institutions trade federal funds (balances held at Federal Reserve Banks) with each other overnight. When a depository institution has surplus balances in its reserve account, it lends to other banks in need of larger balances. In simpler terms, a bank with excess cash, which is often referred to as liquidity, will lend to another bank that needs to quickly raise liquidity. (1) The rate that the borrowing institution pays to the lending institution is determined between the two banks; the weighted average rate for all of these types of negotiations is called the effective federal funds rate.(2) The effective federal funds rate is essentially determined by the market but is influenced by the Federal Reserve through open market operations to reach the federal funds rate target.(2)

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets eight times a year to determine the federal funds target rate. As previously stated, this rate influences the effective federal funds rate through open market operations or by buying and selling of government bonds (government debt).(2) More specifically, the Federal Reserve decreases liquidity by selling government bonds, thereby raising the federal funds rate because banks have less liquidity to trade with other banks. Similarly, the Federal Reserve can increase liquidity by buying government bonds, decreasing the federal funds rate because banks have excess liquidity for trade. Whether the Federal Reserve wants to buy or sell bonds depends on the state of the economy. If the FOMC believes the economy is growing too fast and inflation pressures are inconsistent with the dual mandate of the Federal Reserve, the Committee may set a higher federal funds rate target to temper economic activity. In the opposing scenario, the FOMC may set a lower federal funds rate target to spur greater economic activity. Therefore, the FOMC must observe the current state of the economy to determine the best course of monetary policy that will maximize economic growth while adhering to the dual mandate set forth by Congress. In making its monetary policy decisions, the FOMC considers a wealth of economic data, such as: trends in prices and wages, employment, consumer spending and income, business investments, and foreign exchange markets.

The federal funds rate is the central interest rate in the U.S. financial market. It influences other interest rates such as the prime rate, which is the rate banks charge their customers with higher credit ratings. Additionally, the federal funds rate indirectly influences longer- term interest rates such as mortgages, loans, and savings, all of which are very important to consumer wealth and confidence.(2)

References

(1) Federal Reserve Bank of New York. "Federal funds." Fedpoints, August 2007.

(2) Monetary Policy, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Suggested Citation:

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Federal Funds Effective Rate [DFF], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DFF, April 12, 2024.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Release: Consumer Price Index

Units: Index 1982-1984=100, Seasonally Adjusted

Frequency: Monthly

Notes:

The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items (CPIAUCSL) is a price index of a basket of goods and services paid by urban consumers. Percent changes in the price index measure the inflation rate between any two time periods. The most common inflation metric is the percent change from one year ago. It can also represent the buying habits of urban consumers. This particular index includes roughly 88 percent of the total population, accounting for wage earners, clerical workers, technical workers, self-employed, short-term workers, unemployed, retirees, and those not in the labor force.

The CPIs are based on prices for food, clothing, shelter, and fuels; transportation fares; service fees (e.g., water and sewer service); and sales taxes. Prices are collected monthly from about 4,000 housing units and approximately 26,000 retail establishments across 87 urban areas. To calculate the index, price changes are averaged with weights representing their importance in the spending of the particular group. The index measures price changes (as a percent change) from a predetermined reference date. In addition to the original unadjusted index distributed, the Bureau of Labor Statistics also releases a seasonally adjusted index. The unadjusted series reflects all factors that may influence a change in prices. However, it can be very useful to look at the seasonally adjusted CPI, which removes the effects of seasonal changes, such as weather, school year, production cycles, and holidays.

The CPI can be used to recognize periods of inflation and deflation. Significant increases in the CPI within a short time frame might indicate a period of inflation, and significant decreases in CPI within a short time frame might indicate a period of deflation. However, because the CPI includes volatile food and oil prices, it might not be a reliable measure of inflationary and deflationary periods. For a more accurate detection, the core CPI (CPILFESL) is often used. When using the CPI, please note that it is not applicable to all consumers and should not be used to determine relative living costs. Additionally, the CPI is a statistical measure vulnerable to sampling error since it is based on a sample of prices and not the complete average.

For more information on the consumer price indexes, see:

Bureau of Economic Analysis. "CPI Detailed Report." 2013.

Handbook of Methods

Understanding the CPI: Frequently Asked Questions

Suggested Citation:

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average [CPIAUCSL], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAUCSL, April 12, 2024.

RELEASE TABLES

RELATED DATA AND CONTENT

Data Suggestions Based On Your Search

Content Suggestions

Other Formats

Market Yield on U.S. Treasury Securities at 10-Year Constant Maturity, Quoted on an Investment Basis

Annual, Not Seasonally Adjusted Monthly, Not Seasonally Adjusted Weekly, Not Seasonally AdjustedFederal Funds Effective Rate

Annual, Not Seasonally Adjusted Biweekly, Not Seasonally Adjusted Daily, Not Seasonally Adjusted Monthly, Not Seasonally Adjusted Weekly, Not Seasonally AdjustedConsumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average

Monthly, Not Seasonally Adjusted Semiannual, Not Seasonally Adjusted