‘I’ve just found the original rehearsal tapes,” says William Forsythe. “It is hilarious. We are all 12 years old.” The choreographer is talking about In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated, created for the Paris Opera Ballet in 1987 – the work that changed ballet for ever.

It began that night with two ballerinas in green leotards and black tights, insolently and insouciantly standing on an empty stage, weighing each other up. They pushed their elegant toes into the floor, and looked upwards at the two golden cherries that hung there – the somewhat elevated objects of the title. Then, with a slight shrug, one stalked off, leaving the stage to the other, who began to dance in a jolting crash of electronic sound.

It was thrilling, a high-voltage shock to the world of ballet that would spread far from the stage of the Opera Garnier. It wasn’t the first ballet that Forsythe had made for Paris Opera Ballet at the request of its then director Rudolf Nureyev – that was France/Dance, a little piece featuring famous Paris landmarks passing by on a conveyor belt and starring a young Sylvie Guillem.

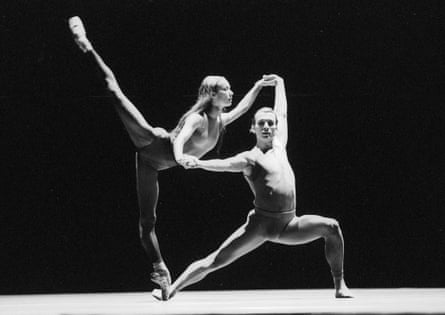

But In the Middle was the one that illuminated everything around it, that made its creator and dancers international names to be reckoned with. The first cast included Guillem, Laurent Hilaire, Isabelle Guérin and Manuel Legris, the stunning generation that Nureyev plucked from the corps de ballet and turned into stars. They were called his chou chou but Forsythe today describes them as wunderkinder – young dancers who could do anything asked of them.

They all looked sensational as they propelled themselves through the work’s off-centre balances, its pulsing, shifting symmetries and casual but charged encounters. “The whole atmosphere there was electric,” Forsythe remembers. “Nureyev had an idea about excellence and he imposed that idea. That generation was one of the finest to come out of the company.”

Such was the impact of In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated that it has become Forsythe’s most famous work, danced worldwide by companies from the Mariinsky to the São Paulo Companhia de Dança from Brazil. Now English National Ballet are giving their first performance of the work, as part of a bill called Modern Masters at Sadler’s Wells. It represents quite a challenge, but as Barry Douglas, one of the dancers says: “You see Sylvie Guillem on the DVD and think, ‘Oh my God, I would love to do this piece. It’s just so exciting.”

Ballet is all about history, or rather about the shifting allegiance of the present to the past. It is the only art form that, until very recently, was passed down “arm to arm, leg to leg” as the Russians say, with a dancer of one generation teaching a role to the next. Reverence for tradition is ingrained into its actual form.

But it is not preserved in aspic. The great classics such as Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty and Giselle have been adapted for different audiences. New choreographers have come along and rethought the uses of traditional steps. George Balanchine arrived in the US from Europe and developed his 20th‑century neoclassical style.

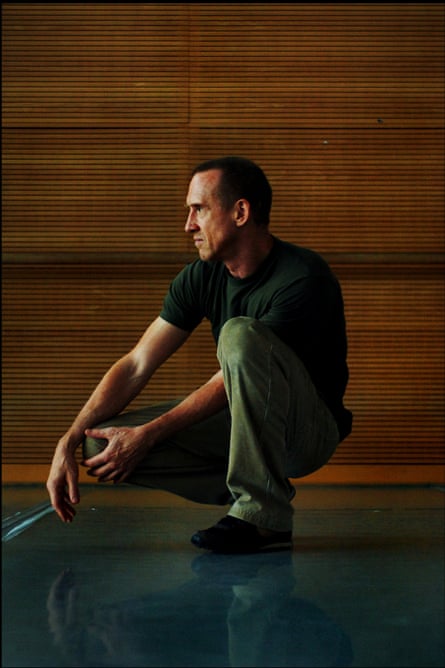

Nobody knows and understands more about this great tradition than Forsythe, a voracious student of dance history who has been known to lose evenings of his life to studying and analysing the performances of the past on YouTube.

Born in New York in 1949, he only started formal dance training in his late teens. But there was no stopping him; he trained in Florida and danced with the Joffrey Ballet, before joining John Cranko’s Stuttgart Ballet in 1973, where he began to choreograph in earnest. In 1984, he was appointed artistic director of Ballet Frankfurt, and promptly transformed it into one of the most dazzling dance companies in the world.

Throughout this progression, he was seen as the natural heir to Balanchine, a lineage that timing alone made seem inevitable. He told me recently, for example, that France/Dance, created in 1983, the year of Balanchine’s death, was “reflecting on the passing of Balanchine. I thought if he had seen Guillem it would have been a revelation to him. He would certainly have appreciated her gifts, and I was sad he wasn’t there to do so.”

But for all his technical brilliance, Forsythe was no Balanchine. His interests were always propelling him far away from elegant abstraction or traditional narrative. “I had to find my way around Balanchine, Petipa, Cranko, MacMillan, the whole crowd,” he once explained. “I realised I had to move on.” He is consequently the only choreographer who has ever been mentioned in the same sentence as the philosopher Michel Foucault, applying a similar critical intelligence to the nature of dance and its language, asking people not just to watch dance, but to analyse what they are watching and understand how dancers themselves think, how steps are forged, how spaces, shapes and scores are created. His entire career, as Ballet Frankfurt morphed into the smaller and even more experimental Forsythe Company in 2004, has been an exploration that has taken him far from his balletic origins. “No one ever participated in the big conversation by saying the same thing over and over again,” he says. “You have to see what is possible.”

Even in 1987 he was well on the road. In the Middle was always conceived as the central abstract act of a larger work called Impressing the Czar, which Forsythe mounted in Frankfurt a year later. “I was very economical in those days and I didn’t have much time to rehearse in Frankfurt, so I thought I could make part of it in Paris and bring it back.” The full-length piece explores the decline of western civilisation, with characters including Saint Sebastian and the Brothers Grimm and a conclusion that sees the entire cast dressed as schoolgirls flying around the stage in a bacchanalian celebration of the power of dance.

In this context, In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated – which, despite its fierce, modern appearance is structured as a very traditional theme and variations – seems to represent a classic order tilting towards change and disruption. Forsythe describes it as “extending and accelerating the traditional figures of ballet. By shifting the alignment of positions and the emphasis of transitions, the enchainments begin to tilt obliquely and receive an unexpected drive that makes them appear at odds with their origins.”

Such statements, while true, fail to communicate the visceral impact of the piece. It has an almost elemental energy as it sets its six women and three men prowling around the stage, like fierce creatures exploring an alien space. Where most dance faces the front of the stage, these nine face all directions, their solos and duets deliberately disrupting the focus. Balletic formality is jettisoned in favour of a wild, off‑kilter theatricality that rethought conventions even as it held them up to the sharp, bright light.

The mood is set by Thom Willems’ powerful, pounding score, written in a strict 4/4 time signature in the studio next door to where Forsythe was working with the Paris Opera Ballet dancers. It sends electronic shudders through the piece, adding to its impact. Guillem said, when the work was revived for the Royal Ballet in 1992, with her and Hilaire once again dancing the central duet:“I think of nothing while I am doing In the Middle, except the steps. They take a real physical power and violence to perform and that is all that is in my mind at that moment: line and power.”

Agnès Noltenius, who danced in the work with Frankfurt Ballet and is now coaching English National Ballet for their performances, takes a similarly pure approach. “Forsythe asked us to think about the geometric relationship between different parts of the body. He doesn’t want people to dance as one block, but to really articulate each part of the body.

“It is a different way of thinking about dance and what the body can achieve. It arrives at a point where you can see people can’t go any further. The body can’t do any more. That is what makes the piece so strong.”

The timing of the revival has particular relevance. At 65, Forsythe has stepped down from the running of his self-named company and will become associate choreographer back with Paris Opera Ballet, where he will create one new piece every year under the aegis of its new director Benjamin Millepied. He has also taken up a teaching post with the Glorya Kaufman School of Dance in southern California, returning to his American roots. Meanwhile Guillem, now 50, is embarking on her farewell tour in a bill of new contemporary creations.

There couldn’t be a better time to look back to that moment which they both began to suggest that ballet was a world of infinite possibility. As Noltenius says: “After this emblematic piece, classical ballet was not the same any more. For 25 years, people have been inspired by it. And they still are.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion