It sounds like every composer’s dream – a kind of music that eliminates the performer (and all the uncertainty and capriciousness that the performer represents). What is called Electronic Music, as developed in the broadcasting studios of Westdeutscher Rundfunk in Cologne, allows the composer himself to build his composition from pure sounds electronically prefabricated. The result, in the form of a tape, comes directly to the listener through the play-back mechanism of a tape-recorder.

The apparatus used to produce this music is less novel and less baffling than might be expected. In a studio smaller than an average living room one is shown two magnetophones (superior tape-recording machines very like those used by the BBC) and two tone-generators. The latter are instruments which produce notes of any desired frequency – and thus of any desired pitch. A frequency of 440 cycles a second, for instance, represents the note A above middle C on the piano.

With this basic apparatus and not much else, the composer first of all selects the frequencies he wants to use. These he records on tape. Then, by a process of recording, rerecording, and editing, he eventually arrives – helped usually by an engineering technician – at a composite assembly of sounds on a single tape, corresponding to his wishes as regards sequence, pitch, loudness, and tone-colour. He has, in fact, assembled his composition.

Weeks for minutes

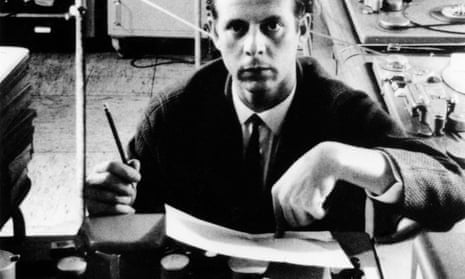

The director of the electronic music establishment in Cologne, Dr Herbert Eimert, is a man of 60. The other composers who have worked there – and “worked” means working in the studio, spending perhaps several weeks conceiving and constructing a piece lasting three or four minutes – are nearly all considerably younger. The most prominent is Karlheinz Stockhausen, aged 28, who has also won notice for his non-electric (but still very radical) compositions. Eimert, Stockhausen, and their fellow-workers have harnessed the technique of electronic music to the service of the “serialist” method of composition. Schoenberg’s twelve-note revolution they accept as history; their own starting-point is the music of Schoenberg’s disciple, Webern, in which every individual note is born of a complex of quasi-mathematical calculation. Eimert edits a periodical significantly called Die Reihe (row or ‘series’ in the musical sense). In the first number, obtainable from Universal Edition and giving excellent documentation on electronic music, he proclaims that serialism “extends rational control over all the elements of music.”

The possibilities of rational calculation are indeed enhanced by electronic music. The composer, no longer confined to tones and semitones, can sub-divide the octave as he likes (even down to twelfths of a tone). Loudness, hitherto expressed by mere approximations, is available in some 40 graded strength. Tone-colour, corresponding to that of various instruments or of no instruments at all, can be built up by harmonic combinations of the “pure” tones issuing from the tone-generator.

In a private house just outside Cologne I listened to Stockhausen expounding his vision and illustrating it with compositions by himself and others. Such compositions would probably seem wildly incomprehensible to the moderately sophisticated listener. This is not because the music is electronic, but because it is serial, without themes and without recapitulations. It is the opinion of Dr Werner Meyer-Eppler, scientific adviser to the Cologne project and head of the unique Institute for Phonetics and Communications Research at the University of Bonn, that the serialists who at present virtually monopolise electronic music have exploited only a little of its scope.

Cloistered relationship

Electronic music, which begins with sounds produced electronically in the studio, is to be differentiated from the Concrete Music of French radio engineers, who start with “real” sounds (a piano’s note, an engine whistle, and what not) and apply electronic treatment only to those. But both are types of music which exist only on a tape or disc. In abolishing the performer they abolish the performance. The social and psychological complexity which constitutes a public concert is replaced by the cloistered relationship between an individual and his loudspeaker.

Even in Germany, electronic music has barely touched the general musical public. But certain adventurous British composers, and even certain sober BBC officials are taking an interest in it. They have examined the first score of electronic music to be published (also by Universal Edition), Stockhausen’s Study No 2. Score, did I say? But it renounces normal notation. Along a time-base it plots, in the form of a graph, pitch, and loudness. It is not a score that anyone can play. It is a diagram from which a technician anywhere in the world could construct a tape which would produce a sound identical with Stockhausen’s original. O brave new world …

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion