Trending

This story is from October 25, 2021

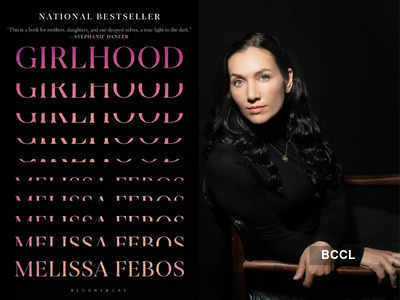

I didn’t derive any sexual pleasure from spitting; only psychological: Melissa Febos in 'Girlhood'

American writer, professor Melissa Febos' latest book 'Girlhood', a collection of essays was published in India in September 2021 by Bloomsbury. Here's an exclusive excerpt from it.

'Girlhood' by Melissa Febos

American writer, professor Melissa Febos is best known for her debut book 'Whip Smart', a memoir which was published in 2010. In her memoir, Melissa opened up about her unconventional job as a professional dominatrix, a work which she did while she was studying at The New School. The book was critically acclaimed and it was followed by the essay collections 'Abandon Me' in 2017 and more recently 'Girlhood', which was published in India in September 2021 by Bloomsbury.While 'Abandon Me' was a LAMBDA Literary Award finalist, her third book 'Girlhood' became an instant bestseller in the USA. As the title suggests, 'Girlhood' is about what it really means to be female and what it means to free oneself from others expectations. "It is in part by writing this book that I have corrected the story of my owngirlhood and found ways to recover myself. I have found company in the stories of other women, and the revelation of all our ordinariness has itself been curative. Writing has always been a way to reconcile my lived experience with the narratives available to describe it (or lack thereof). My hope is that these essays do some of that work for you, too," Melissa writes in the prologue of the book.

Read an exclusive excerpt from Melissa Febos' latest essay collection 'Girlhood' here:

KETTLE HOLES

“What do you like?” the men would ask. “Spitting,” I’d say. To even utter the word felt like the worst kind of cuss, and I trained myself not to flinch or look away or offer a compensatory smile after I said it. In the dungeon’s dim rooms, I unlearned my instinct for apology. I learned to hold a gaze. I learned the pleasure of cruelty.

It was not true cruelty, of course. My clients paid $75 an hour to enact their disempowerment. The sex industry is a service industry, and I served humiliation to order. But the pageant of it was the key. To spit in an unwilling face was inconceivable to me and still is. But at a man who had paid for it?

They knelt at my feet. They crawled naked across gleaming wood floors. They begged to touch me, begged for forgiveness. I refused. I leaned over their plaintive faces and gathered the wet in my mouth. I spat. Their hard flinch, eyes clenched. The shock of it radiated through my body, then settled, then swelled into something else.

“Do you hate men?” people sometimes asked.

“Not at all,” I answered.

“You must work out a lot of anger that way,” they suggested.

“I never felt angry in my sessions,” I told them. I often explained that the dominatrix’s most useful tool was a well-developed empathic sense. What I did not acknowledge to any curious stranger, or to myself, was that empathy and anger are not mutually exclusive.

We are all unreliable narrators of our own motives. And feeling something neither proves nor disproves its existence. Conscious feelings are no accurate map to the psychic imprint of our experiences; they are the messy catalog of emotions once and twice and thrice removed, often the symptoms of what we won’t let ourselves feel. They are not Jane Eyre’s locked-away Bertha Mason, but her cries that leak through the floorboards, the fire she sets while we sleep and the wet nightgown of its quenching.

I didn’t derive any sexual pleasure from spitting, I assured people. Only psychological. Now, this dichotomy seems flimsy at best. How is the pleasure of giving one’s spit to another’s hungry mouth not sexual? I needed to distinguish that desire from what I might feel with a lover. I wanted to divorce the pleasure of violence from that of sex. But that didn’t make it so.

It was the thrill of transgression, I said. Of occupying a male space of power. It was the exhilaration of doing the thing I would never do, was forbidden to do by my culture and by my conscience. I believed my own explanations, though now it is easy to poke holes in them.

I did not want to be angry. What did I have to be angry about? My clients sought catharsis through the reenactment of childhood traumas. They were hostages to their pasts, to the people who had disempowered them. I was no such hostage— I did not even want to consider it. I wanted only to be brave and curious and in control. I did not want my pleasure to be any kind of redemption. One can only redeem a thing that has already been lost or taken. I did not want to admit that someone had taken something from me.

His name was Alex, and he lived at the end of a long unpaved driveway off the same wooded road that my family did. It took ten minutes to walk between our homes, both of which sat on the bank of Deep Pond. Like many of the ponds on Cape Cod, ours formed some fifteen thousand years ago when a block of ice broke from a melting glacier and drove deep into the solidifying land of my future backyard. When the ice block melted, the deep depression filled with water and became what is called a kettle-hole lake.

Despite its small circumference, our pond plummeted fifty feet at its deepest point. My brother and I and all the children raised on the pond spent our summers getting wet, chasing one another through invented games, our happy screams garbled with water. I often swam out to the deepest point—not the center of the pond, but to its left—and trod water over this heart cavity. In summer, the sun warmed the surface to bath temperatures, but a few feet deeper it went cold. Face warm, arms flapping, I dangled my feet into that colder depth and shivered. Fifty feet was taller than any building in our town, was more than ten of me laid head to foot. It was a mystery big enough to hold a whole city. I could swim in it my whole life and never know what lay at its bottom.

An entry in my diary from age ten announces: “Today Alex came over and swam with us. I think he likes me.”

Alex was a grade ahead of me and a foot taller. He had a wide mouth, tapered brown eyes, and a laugh that brayed clouds in the chill of fall mornings at our bus stop. He wore the same shirt for four out of five school days, and I thought he was beautiful. I had known Alex for years, but that recorded swim is the first clear memory I have of him. A few months later, he spat on me for the first time.

When I turned eleven, I enrolled in the public middle school with all the other fifth-and sixth-graders in our town. The new bus stop was farther down the wooded road, where it ended at the perpendicular intersection of another. On that corner was a large house, owned by Robert Ballard, the oceanographer who discovered the wreck of the Titanic in 1985. Early in his career, Ballard had worked with the nearby Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and it was during his deep- sea dives off the coast of Massachusetts that his obsession with shipwrecks was born. Sometimes I studied that house—its many gleaming windows and ivy-choked tennis court—and thought about the difference between Ballard and my father, who was a captain in the merchant marines. One man carried his cargo across oceans; the other ventured deep inside them to discover his. I was drawn to the romance of each: to slice across the glittering surface, and also to plunge into the cold depths. A stone wall wrapped around Ballard’s yard. Here, we

waited for the school bus.

I read books as I walked to the bus stop. Reading ate time. Whole hours disappeared in stretches. It shortened the length of my father’s voyages, moved me closer to his returns with every page. I was a magician with a single power: to disappear the world. I emerged from whole afternoons of reading, my life a foggy half-dream

through which I drifted as my self bled back into me like steeping tea.

The start of fifth grade marked more change than the location of my bus stop. My parents had separated that summer.

My body, that once reliable vessel, began to transform. But what emerged from it was no happy magic, no abracadabra. It went kaboom. The new body was harder to disappear.

“I wish people didn’t change sometimes,” I wrote in my diary. By people, I meant my parents. I meant me. I meant the boy who swam across that lake toward my new body with its power to compel but not control.

Before puberty, I moved through the world and toward other people without hesitance or self-consciousness. I read hungrily and kept lists of all the words I wanted to look up in a notebook with a red velvet cover. I still have the notebook. “Ersatz,” it reads. “Entropy. Mnemonic. Morass. Corpulent. Hoary.” I was smart and strong and my power lay in these things alone. My parents loved me well and mirrored these strengths back to me.

Perhaps more so than other girls’, my early world was a safe one. My mother banned cable TV and sugar cereals, and made feminist corrections to my children’s books with a Sharpie. When he was home from sea, my father taught me how to throw a baseball and a punch, how to find the North Star, and start a fire. I was protected from the darker leagues of what it meant to be female. I think now of the Titanic—not the familiar tragedy of its wreck, the scream of ice against her starboard flank, the thunder of seawater gushing through her cracked hull. I think of the short miracle of her passage. The 375 miles she floated, immaculate, across the Atlantic.

My early passage was a miracle, too. Like the Titanic’s, it did not last.

Read an exclusive excerpt from Melissa Febos' latest essay collection 'Girlhood' here:

KETTLE HOLES

“What do you like?” the men would ask. “Spitting,” I’d say. To even utter the word felt like the worst kind of cuss, and I trained myself not to flinch or look away or offer a compensatory smile after I said it. In the dungeon’s dim rooms, I unlearned my instinct for apology. I learned to hold a gaze. I learned the pleasure of cruelty.

It was not true cruelty, of course. My clients paid $75 an hour to enact their disempowerment. The sex industry is a service industry, and I served humiliation to order. But the pageant of it was the key. To spit in an unwilling face was inconceivable to me and still is. But at a man who had paid for it?

They knelt at my feet. They crawled naked across gleaming wood floors. They begged to touch me, begged for forgiveness. I refused. I leaned over their plaintive faces and gathered the wet in my mouth. I spat. Their hard flinch, eyes clenched. The shock of it radiated through my body, then settled, then swelled into something else.

“Do you hate men?” people sometimes asked.

“Not at all,” I answered.

“You must work out a lot of anger that way,” they suggested.

“I never felt angry in my sessions,” I told them. I often explained that the dominatrix’s most useful tool was a well-developed empathic sense. What I did not acknowledge to any curious stranger, or to myself, was that empathy and anger are not mutually exclusive.

We are all unreliable narrators of our own motives. And feeling something neither proves nor disproves its existence. Conscious feelings are no accurate map to the psychic imprint of our experiences; they are the messy catalog of emotions once and twice and thrice removed, often the symptoms of what we won’t let ourselves feel. They are not Jane Eyre’s locked-away Bertha Mason, but her cries that leak through the floorboards, the fire she sets while we sleep and the wet nightgown of its quenching.

I didn’t derive any sexual pleasure from spitting, I assured people. Only psychological. Now, this dichotomy seems flimsy at best. How is the pleasure of giving one’s spit to another’s hungry mouth not sexual? I needed to distinguish that desire from what I might feel with a lover. I wanted to divorce the pleasure of violence from that of sex. But that didn’t make it so.

It was the thrill of transgression, I said. Of occupying a male space of power. It was the exhilaration of doing the thing I would never do, was forbidden to do by my culture and by my conscience. I believed my own explanations, though now it is easy to poke holes in them.

I did not want to be angry. What did I have to be angry about? My clients sought catharsis through the reenactment of childhood traumas. They were hostages to their pasts, to the people who had disempowered them. I was no such hostage— I did not even want to consider it. I wanted only to be brave and curious and in control. I did not want my pleasure to be any kind of redemption. One can only redeem a thing that has already been lost or taken. I did not want to admit that someone had taken something from me.

His name was Alex, and he lived at the end of a long unpaved driveway off the same wooded road that my family did. It took ten minutes to walk between our homes, both of which sat on the bank of Deep Pond. Like many of the ponds on Cape Cod, ours formed some fifteen thousand years ago when a block of ice broke from a melting glacier and drove deep into the solidifying land of my future backyard. When the ice block melted, the deep depression filled with water and became what is called a kettle-hole lake.

Despite its small circumference, our pond plummeted fifty feet at its deepest point. My brother and I and all the children raised on the pond spent our summers getting wet, chasing one another through invented games, our happy screams garbled with water. I often swam out to the deepest point—not the center of the pond, but to its left—and trod water over this heart cavity. In summer, the sun warmed the surface to bath temperatures, but a few feet deeper it went cold. Face warm, arms flapping, I dangled my feet into that colder depth and shivered. Fifty feet was taller than any building in our town, was more than ten of me laid head to foot. It was a mystery big enough to hold a whole city. I could swim in it my whole life and never know what lay at its bottom.

An entry in my diary from age ten announces: “Today Alex came over and swam with us. I think he likes me.”

Alex was a grade ahead of me and a foot taller. He had a wide mouth, tapered brown eyes, and a laugh that brayed clouds in the chill of fall mornings at our bus stop. He wore the same shirt for four out of five school days, and I thought he was beautiful. I had known Alex for years, but that recorded swim is the first clear memory I have of him. A few months later, he spat on me for the first time.

When I turned eleven, I enrolled in the public middle school with all the other fifth-and sixth-graders in our town. The new bus stop was farther down the wooded road, where it ended at the perpendicular intersection of another. On that corner was a large house, owned by Robert Ballard, the oceanographer who discovered the wreck of the Titanic in 1985. Early in his career, Ballard had worked with the nearby Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and it was during his deep- sea dives off the coast of Massachusetts that his obsession with shipwrecks was born. Sometimes I studied that house—its many gleaming windows and ivy-choked tennis court—and thought about the difference between Ballard and my father, who was a captain in the merchant marines. One man carried his cargo across oceans; the other ventured deep inside them to discover his. I was drawn to the romance of each: to slice across the glittering surface, and also to plunge into the cold depths. A stone wall wrapped around Ballard’s yard. Here, we

waited for the school bus.

I read books as I walked to the bus stop. Reading ate time. Whole hours disappeared in stretches. It shortened the length of my father’s voyages, moved me closer to his returns with every page. I was a magician with a single power: to disappear the world. I emerged from whole afternoons of reading, my life a foggy half-dream

through which I drifted as my self bled back into me like steeping tea.

The start of fifth grade marked more change than the location of my bus stop. My parents had separated that summer.

My body, that once reliable vessel, began to transform. But what emerged from it was no happy magic, no abracadabra. It went kaboom. The new body was harder to disappear.

“I wish people didn’t change sometimes,” I wrote in my diary. By people, I meant my parents. I meant me. I meant the boy who swam across that lake toward my new body with its power to compel but not control.

Before puberty, I moved through the world and toward other people without hesitance or self-consciousness. I read hungrily and kept lists of all the words I wanted to look up in a notebook with a red velvet cover. I still have the notebook. “Ersatz,” it reads. “Entropy. Mnemonic. Morass. Corpulent. Hoary.” I was smart and strong and my power lay in these things alone. My parents loved me well and mirrored these strengths back to me.

Perhaps more so than other girls’, my early world was a safe one. My mother banned cable TV and sugar cereals, and made feminist corrections to my children’s books with a Sharpie. When he was home from sea, my father taught me how to throw a baseball and a punch, how to find the North Star, and start a fire. I was protected from the darker leagues of what it meant to be female. I think now of the Titanic—not the familiar tragedy of its wreck, the scream of ice against her starboard flank, the thunder of seawater gushing through her cracked hull. I think of the short miracle of her passage. The 375 miles she floated, immaculate, across the Atlantic.

My early passage was a miracle, too. Like the Titanic’s, it did not last.

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA