But this example illustrates why the labor/capital distinction has become harder to draw in late capitalism. In one sense, calling athletes “laborers” makes sense because they’re paid to train and play games, which is a form of labor. But many professional athletes make a lot more money from endorsements and advertising than they do from playing. Are those athletes really “laborers” when most of their income derives from their image, rather than any specific work they perform? Is an athlete’s personal image really “labor” rather than “capital”? More fundamentally, would rich professional athletes tangibly benefit from a socialist revolution?

Just as it’s difficult to isolate “labor,” it’s also sometimes hard to locate the means of production with any precision. In Marx’s world, the means of production were concrete: industrial machines that laborers operated to make products. That’s still true in some industries, like manufacturing, but what about information-based industries? Picture a software developer. The “product” she makes is computer code. What are the “means of production” for computer code? The simplest answer is a computer, coupled with a programming language and a code editor. But most software developers probably have their own computers, and most programming languages and code editors are open-source. In that sense, software engineers own the “means of production” for the product they make – whereas an assembly-line worker doesn’t own the assembly line. Yet software developers are undoubtedly “laborers” under a traditional Marxist analysis.

None of this undermines Marx’s basic point that labor and capital have antagonistic interests. But the existence of the middle class, coupled with the transition of advanced economies from manufacturing-based to information-based industries, has made it more difficult to figure out who’s the capitalist and who’s the laborer. That necessarily inhibits the development of class consciousness.

A Politics of Personal Identity

These conditions have made it difficult for the American left to organize around class. Instead, throughout modern American history, most leftist political movements have centered on identity – race, ethnicity, gender, gender orientation, sexuality, etc. Of course, there have been some exceptions; Eugene Debs, the brief prominence of the Industrial Workers of the World in the ‘20s and ‘30s, and more recently, Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaign spring to mind.

But in terms of both numbers and influence, class-based leftist movements pale in comparison to identity-centric efforts like the civil rights movement, the women’s liberation movement, and the Black Lives Matter protests. Because Americans don’t strongly perceive themselves in terms of class, it’s difficult to organize class-based leftist political activity. This trend is especially stark in the twenty-first century. By far the biggest left-leaning political movement in America in the past few decades is the Black Lives Matter protests against racially-motivated police violence. The largest confluence of protests occurred in the summer of 2020 and involved around 20 million participants – making the protests one of the largest social movements in American history.[14] Other contemporary rallying points for the left include abortion and LGBTQ rights, which are identity-centric issues.

To give credit where it’s due, identity politics has produced some remarkable results. Although the Black Lives Matter protests haven’t achieved much tangible progress on police violence – police shootings per capita have actually increased since the protests began[15] – the movement galvanized a generation of Americans into leftist politics. And thanks to relentless activism by the LGBTQ community, in the past twenty years, Americans’ views on gay rights underwent an astonishing reversal; in 2004, 60% of Americans opposed gay marriage, while in 2019, 61% favored it.[16]

It’s also worth noting that approaches to leftist politics that emphasize only class, to the exclusion of other predicates of oppression, alienate potential supporters and ignore the manifold forms of structural violence that afflict society. For example, some socialists have tried to reframe police violence as a primarily class-based issue. But while police are more likely to kill poor people, class explains a mere 28% of the disproportionately high rate of police violence against Black people.[17] By the numbers, police violence is primarily a race issue.

For that reason, proponents of identity politics often accuse socialists of “class-reductionism.”[18] But while this is sometimes fair criticism, more often than not, the exact opposite is true – movements centered around one type of personal identity conceptualize every political struggle in terms of that identity, replacing “class-reductionism” with race- or gender- or sexuality- reductionism. That tendency both inhibits class consciousness and causes a fundamental misunderstanding of key political issues, to the strategic detriment of the left.

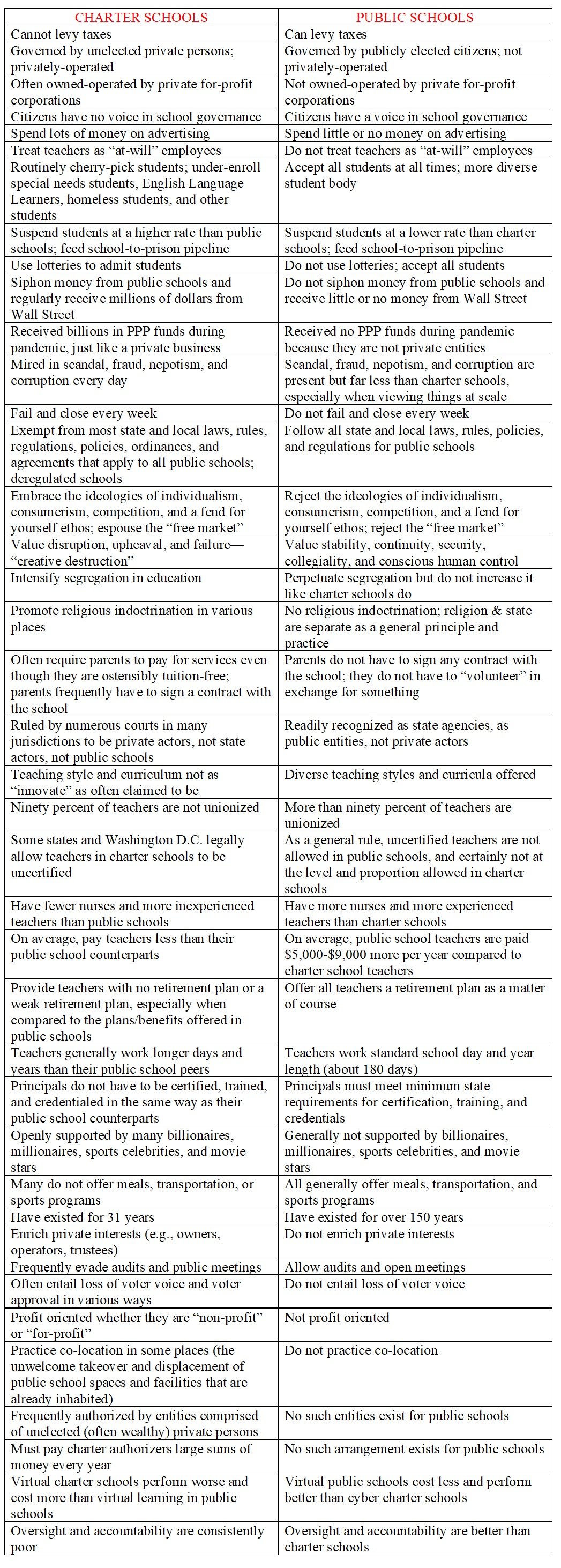

The “school-to-prison pipeline” is a case in point. The phrase refers to the tendency of some schools to apply harsh disciplinary policies and refer students who break the rules to law enforcement. This is pervasive at low-income, predominantly Black and Latinx schools, and was the subject of one of the most widely-read leftist books this century – Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. Following in Alexander’s footsteps, virtually every framing of the school-to-prison pipeline fixates on race-based disparities in school discipline and incarceration. Google “school-to-prison pipeline,” and you’ll find that one of the first results defines it as “practices and policies that disproportionately place students of color into the criminal justice system.”[19] Class doesn’t even get a mention.

But while there are doubtless real differences in the outcomes Black and white adolescents face in school and the justice system, the majority of those differences are attributable to class, not race. According to one comprehensive study, about a third of the discipline gap between Black and white students cannot be explained by poverty, disciplinary histories, and school district characteristics.[20] Obviously this indicates that a disturbing share of the gap in school discipline stems from pure racism, but don’t miss the forest for the trees: two-thirds of the gap is attributable to the material economic conditions of the students. Another study found that although Black men are significantly more likely to face incarceration than their white counterparts, a majority of that disparity (between 54 and 85%, depending on the definition of “incarceration”) is attributable to class.[21] In sum, most of the people who traverse the school-to-prison pipeline – and face subsequent terms of incarceration – do so because they’re poor, not because they’re Black.

The way we talk about these issues has strategic consequences. A poor white person hearing about the school-to-prison pipeline might decide that the issue isn’t important to him because it’s unlikely to affect his kids – an incorrect conclusion founded on an inaccurate framing of the issue. The school-to-prison pipeline is a class issue, but because leftist politics centers on personal identity, discourse on the school-to-prison pipeline doesn’t promote class consciousness.

Identity politics – or, more accurately, “identity-only politics” – also leaves oppressed groups vulnerable to divide-and-conquer tactics by the right, which further inhibit class consciousness. The artificial tension between Black people, gay and lesbian people, and trans people is a good example of these tactics. In the early 2010s, the National Organization for Marriage, an anti-gay advocacy group, circulated an astonishingly frank internal memo on how to use gay marriage as a wedge issue. An excerpt reads:

The strategic goal of this project is to drive a wedge between gays and Blacks – two key Democratic constituencies. Find, equip, energize, and connect African American spokespeople for marriage; develop a media campaign around their objections to gay marriage as a civil right; provoke the gay marriage base into responding by denouncing these spokesmen and women as bigots… Find attractive young Black Democrats to challenge white gay marriage advocates electorally.[22]

Later, when trans rights came to prominence in the cultural discourse, right-wing groups pivoted to manufacture another “wedge” between women plus gay and lesbian folks, on the one hand, and trans people on the other. In 2017, Meg Kilgannon, the executive director of Concerned Parents and Education, spoke at a summit hosted by the Family Research Council – a Christian rightist, anti-LGBT organization. Kilgannon laid out a strategy for opposing measures expanding trans rights in schools: portray trans rights as anti-feminist and anti-gay. This would be effective, Kilgannon argued, because “the LGBT alliance is actually fragile and the trans activists need the gay rights movement to help legitimize them.” But for many LGB activists, “gender identity on its own is just a bridge too far. If we separate the T from the alphabet soup we’ll have more success.”[23]

Wedge issues are an insidiously effective way to blunt the efficacy of identity-based leftist politics. Promulgating wedge issues pits oppressed groups against one another, which inhibits the members of those groups from perceiving themselves as part of a single economic class with united interests.

Of course, practitioners of identity politics are not to blame for this unfortunate reality. Most of those folks are sincere advocates for marginalized groups who simply use the most effective political strategies they can muster – and sometimes achieve real progress in their communities. But while leftist politics in America remains centered on personal identity, class consciousness is unlikely to develop.

Conclusion

This analysis of class consciousness in modern America gives rise to several strategic observations. First and foremost, the delicate balance of factors that has allowed the middle class to remain viable for almost a century may be deteriorating. Although factors of convergence have supported the existence of the middle class for the past century or so, those trends seem to be reversing. Near the end of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Piketty suggests that population and economic growth are slowing, inflation is slowly declining, and economic inequality is on the rise in the western world. If the forces of convergence turn into forces of divergence, the classes will slowly stratify, and a degree of class consciousness will probably develop on its own. Socialists should exploit this reality by advancing a class-centric analysis directed at members of the middle class suddenly cast into poverty by these economic trends.

By the same token, leftist generally should recognize that, given the competing substrata of the economy and the multifarious forms of oppression, neither class nor personal identity furnishes a comprehensive answer to all social ills. As discussed, class alone doesn’t provide a satisfactory explanation of police violence, and race alone doesn’t provide a satisfactory explanation of the school-to-prison pipeline. Instead, we should take an empirical approach to confronting specific problems.

Relatedly, leftists should spot wedge issues – which thrive in the areas where two oppressed groups believe their interests are in tension – and avoid schismatic arguments. Instead, leftist analysis should begin with the tangible interests that most oppressed people share. For instance, it is routine to point out that Black women face significant and unfair disparities in pay; women tend to be paid less than men and Black people tend to be paid less than white people, meaning that Black women face compound inequities in their salaries. But discussing pay disparity in terms of identity pits these groups against each other, implying that Black women have different interests from white women and Black men. A better way to frame the issue is to focus on an enemy common to all of those groups – employers, which have overly broad discretion to set their employees’ salaries – and the common problem that results, namely, that workers as a whole are paid too little and unfairly.

By framing issues in terms that take into account both identity and class, socialists can take advantage of rising economic inequality to promote class consciousness. And then, perhaps, we can prove that the revolution was merely deferred – not denied.

Sources

[1] Vladimir Lenin, “Letters from Afar: The First Letter,” Pravda, March 21, 2017, https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/lfafar/first.htm.

[2] Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man (New York: Routledge Classics, 2007), 21-51, available at https://www.cs.vu.nl/~eliens/download/marcuse-one-dimensional-man.pdf.

[3] Loren Balhorn, “The World Revolution that Wasn’t,” Jacobin, March 2, 2019, https://jacobin.com/2019/03/comintern-lenin-german-revolution-ussr-revolution.

[4] Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge: Bellknap Press, 2014), 13-15, 20-27, 69-85, 99-109, 377-393.

[5] Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy (Paris, 1847), available at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/poverty-philosophy/index.htm.

[6] Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York: HarperCollins, 1999), 349, 467.

[7] Jeffrey Wenger and Melanie Zaber, “Most Americans Consider Themselves Middle-Class. But Are They?”, Rand Corporation Blog, May 14, 2021, https://www.rand.org/blog/2021/05/most-americans-consider-themselves-middle-class-but.html.

[8] Heather J. Smith and Yueh J. Juo, “Relative Deprivation: How Subjective Experiences of Inequality Influence Social Behavior and Health,” Policy Insights from Social and Personality Psychology 1, no. 1 (October 1, 2014), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2372732214550165.

[9] “What Percent of Americans Own Stocks?”, FinancialSamurai, 2021, https://www.financialsamurai.com/what-percent-of-americans-own-stocks/.

[10] “Share of Households Owning Mutual Funds in the United States from 1980 to 2019,” Statistica, November 9, 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/246224/mutual-funds-owned-by-american-households/.

[11] Alicia Adamczyk, “25% of Americans Have No Retirement Savings,” CNBC, May 24, 2019, https://www.cnbc.com/2019/05/24/25-percent-of-us-adults-have-no-retirement-savings-fed-finds.html.

[12] Paul Vigna, “The Stock Market Is a Strong Election Day Predictor,” The Wall Street Journal, September 7, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-stock-market-is-a-strong-election-day-predictor-11599490800.

[13] Barry Eidlin, “Last Week’s Pro Athletes Strikes Could Become Much Bigger Than Sports,” Jacobin, August 30, 2020, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2020/08/sports-strikes-kenosha-racial-justice.

[14] Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui, and Jugal Patel, “Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History,” New York Timesx, July 3, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html.

[15] “National Trends,” Mapping Police Violence, last modified September 30, 2022, https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/nationaltrends.

[16] “Attitudes on Same-Sex Marriage,” Pew Research Center, May 14, 2019, https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/fact-sheet/changing-attitudes-on-gay-marriage/.

[17] 3P Staff, “Class and Racial Inequalities in Police Killings,” People’s Policy Project, June 23, 2020, https://www.peoplespolicyproject.org/project/class-and-racial-inequalities-in-police-killings/.

[18] Tatiana Cozzarelli, “Class Reductionism Is Real, and It’s Coming from the Jacobin Wing of the DSA,” LeftVoice, June 16, 2020, https://www.leftvoice.org/class-reductionism-is-real-and-its-coming-from-the-jacobin-wing-of-the-dsa/.

[19] “Who is Most Affected by the School to Prison Pipeline?”, American University School of Education Blog, February 24, 2021, https://soeonline.american.edu/blog/school-to-prison-pipeline/.

[20] Maithreyi Gopalan and Ashlyn Nelson, “Understanding the Racial Discipline Gap in Schools,” American Educational Research Association Vol. 5, No. 2 (April 23, 2019), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2332858419844613.

[21] Nathaniel Lewis, “Mass Incarceration,” People’s Policy Project, 2018, https://www.peoplespolicyproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/MassIncarcerationSummary.pdf.

[22] Brett LoGiurato, “Read The Leaked Anti-Gay Marriage Memo Whose Authors Wanted To ‘Drive A Wedge Between Gays And Blacks’”, Business Insider, May 27, 2012, https://www.businessinsider.com/nom-gay-marriage-memos-drive-a-wedge-between-gays-and-Blacks-2012-3.

[23] Hélène Barthélemy, “Christian Right Tips to Fight Transgender Rights: Separate the T from the LGB,” Southern Poverty Law Center, October 23, 2017, https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2017/10/23/christian-right-tips-fight-transgender-rights-separate-t-lgb.