Arthur Tudor is often overshadowed by his more famous family members. His younger brother, would go on to become the famed King Henry VIII of England, while his niece ruled as the iconic Elizabeth I. Yet, while Henry VIII's rule would mark a period of massive change and historical intrigue—his six wives; his split from the papacy and the start of the English Reformation—and Elizabeth's would mark a golden age for England, Arthur remains famous predominately because of his death.

However, it is only because of Arthur's premature passing that Henry VIII even became king in the first place, and in turn passed his crown (eventually) to Elizabeth. Indeed, by virtue of his death Arthur might well have become one of the most influential figures of English history you've never heard of.

In honor of the Starz's new coming-of-age Tudor drama, Becoming Elizabeth, we take a look at what happened to the lesser-known Tudor brother and how he unintentionally shaped the reigns of two of the country's most famous monarchs.

Who was Arthur, Prince of Wales?

Born in Winchester Castle in September 1486—a scant nine months after his parents's marriage—Arthur was the eldest of King Henry VII's four surviving children with Elizabeth of York. Named after the legendary king of Camelot, Arthur was engaged as a toddler to Catherine of Aragon, the youngest daughter of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, in order to create an alliance between England and Spain.

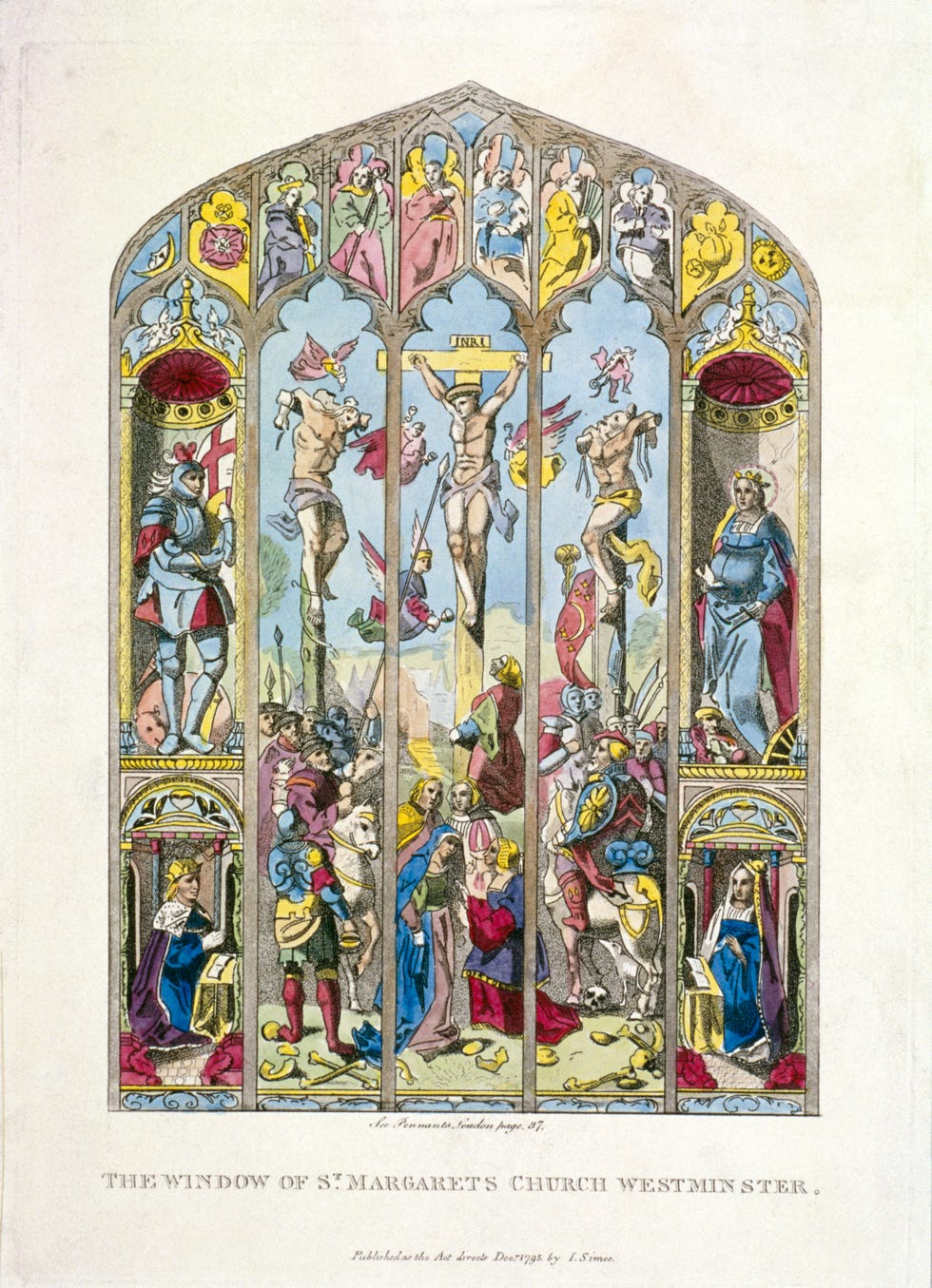

Though it would take several years to secure papal approval for the match, the couple exchanged letters in Latin for some time and finally met not long before their marriage in a lavish celebration at St. Paul's Cathedral in London, in November of 1501.

The state of Arthur's lifelong health has been debated by scholars over the years, with some contradictory evidence on both sides suggesting he may have been sickly as a child, or alternately, perfectly healthy and robust. Regardless of his childhood health, by the time he married Catherine at the age of 15, decline was not far off.

Though the couple was subjected to a bedding ceremony, in which the newlyweds were escorted to a shared bed on their wedding night by members of the court, and were seen to lay down together, Catherine would later insist that the marriage was never consummated, evidently due to to Arthur's infirmity. It was this purported lack of consummation that would ultimately lead to the approval for Catherine to marry Arthur's brother, Henry VIII; doubts over the story would play a significant role in kicking off the English Reformation.

After their wedding, Arthur and Catherine set up their household in Ludlow Castle, on the Welsh border. They lived there together for several months before, in the spring of 1502 both were taken ill with a well-known malady of the time, "sweating sickness." Catherine recovered from the illness; Arthur died of it on April 2, 1502 after a mere five months of marriage.

The English Sweat

Also known as "sweating sickness" and simply "the sweats", the so-called "English Sweat" which claimed Arthur, Price of Wales's life has remained a medical mystery for centuries.

Reaching epidemic proportions on no less than five occasions during the late 15th and early 16th centuries, sweating sickness was highly lethal. Physician John Caius, whose book about the illness remains the most famous account from the time period, noted that death could occur within 3 hours of the onset of symptoms, and that those who survived the first 24 hours would usually make a full recovery (though surviving did not, evidently, prevent the patients from contracting the disease again.)

Sweating sickness was confined almost exclusively to England during its outbreaks, ravaging the wealthy more often than the poor. And yet, for all of its virulence, the sweats seemed to disappear almost as suddenly as they appeared in the first place, with no known outbreaks after 1578.

While the disease's disappearance no doubt saved thousands of lives, it has also stymied modern medical investigators hoping to understand what claimed the life of Arthur and so many of his subjects.

Part of the trouble stems from sweating sickness's symptoms—fever, chills, aches, delirium, and, of course, intense sweating—which are common to a number of diseases including influenza, scarlet fever, and typhus, yet never seem to fit exactly in strength, duration, or combination with any known medical issue. The most common modern theory suggests that the outbreaks may have been a form of hantavirus, similar to the hantavirus pulmonary syndrome that struck the American southwest in the 1990s. Exactly why the virus, if that was indeed the cause, would disappear so suddenly is not known, but some scholars suggest that it could be a result of the virus evolving in a way that made it less deadly or less easily spread to humans.

Why was Arthur so important?

Henry VII (Arthur and Henry VIII's father) spent much of his reign planning out how to maintain the Tudor dynasty's hold on the throne; a goal in which Arthur played a pivotal role.

Not a wildly popular king, Henry VII did not win the throne until he was in his late 20s, having spent much of his life in France in an effort to protect him from Yorkish forces during the War of the Roses. His claim to the throne was also debated, coming down through his mother's side of the family (outside of the conventions of primogeniture). Nonetheless, by his late 20s, Henry VII had found himself the most viable of the potential heirs on the Lancastrian side of the War of the Roses and after defeating Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, he ascended to the throne.

With the crown in place, Henry VII hoped to seal his hold over England by uniting his house with that of his enemies from the war, the House of York. To do so, he married Elizabeth of York, the eldest child of King Edward IV, as seen in The White Princess.

As the heir of both the House of Tudor and the House of York, Arthur was a keystone in Henry VII's plan to maintain peace in the kingdom and prevent rival factions from rising against his claim to the throne. Upon Arthur's death, that mantle fell to Henry VII and Elizabeth's only remaining son, the future King Henry VIII.

How did Arthur's death change history?

Henry VIII's rule had a dramatic and long-lasting impact on European history, in large part because of his years-long quest to create a male Tudor heir to follow him on the throne. He began by marrying Catherine of Aragon, Arthur's widow; a marriage which was only allowed by the Catholic church when Catherine testified that she had never had sexual contact with Arthur.

While Henry VIII and Catherine were apparently happy for many years, the absence of a male heir weighed heavily on Henry VIII, who realized that in failing to provide a direct male heir, he might plunge the country into another civil war upon his death. He began to believe that Catherine might, in fact, have consummated her marriage to his brother and that their inability to have a surviving son together was God's punishment. Along with his infatuation with Anne Boleyn, this inspired Henry VIII to petition the church for a divorce. When the church refused, the irate Henry VIII set about breaking the country away from Catholicism altogether, ultimately forming the Church of England, with himself as the head, to grant his own divorce from Catherine.

If Arthur had not died when he did, he might well have left a male heir of his own, circumventing Henry VIII's claim to the crown. Had he died even a year later, it might have been more difficult for Catherine to argue her virginity, preventing her marriage to Henry VIII and ultimately, possibly, even the formation of the Church of England.

Likewise, it's unlikely that if Arthur had lived, the world would ever have seen the rule of Queen Elizabeth I, the daughter of Henry VIII and his second wife, Anne Boleyn. Nor would, upon Elizabeth I's death, James I have ascended the throne, functionally combining the royal houses of Scotland and England under a single crown.

However, it wasn't only in issues of politics and religion that Arthur's death influenced the world; it also may have changed medical history.

The death of Arthur deeply psychologically effected Henry VIII; he became obsessed with medical science in his adulthood, developing his own treatments and tinctures that he believed would help keep him healthy and free of the clutches of the dreaded sweating sickness. It was this interest that also led Henry to endow the first medical college in England, the Royal College of Physicians (then known as the King’s College of Physicians), which established standards of care and training in the previously unregulated medical field. In doing so, he likely impacted not only the development of medical treatments throughout England, but also the rest of Europe when English-trained doctors practiced abroad.

Lauren Hubbard is a freelance writer and Town & Country contributor who covers beauty, shopping, entertainment, travel, home decor, wine, and cocktails.