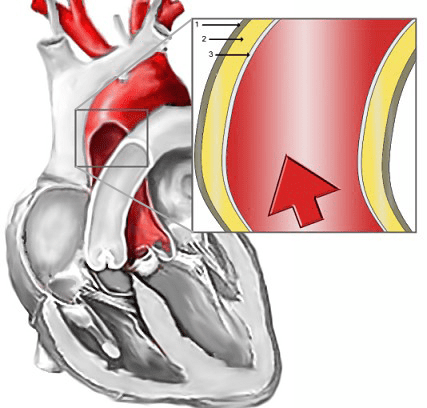

In November 1760, the King of Great Britain rose early as was his custom and drank his habitual cup of chocolate. He then went to use his commode on wheels, and minutes later was discovered slumped on the floor, dead. The next day his physician, Frank Nicholls, “opened the body” and found the king had died from an aortic dissection, a catastrophic event in which blood surges through a rent in the innermost layer of the aorta and dissects its way along the vessel wall.

Many patients with aortic dissection present with severe rending pain in the chest. Some die instantly. A few develop other symptoms depending on where the dissection had occurred. Frank Nicholls achieved fame by describing the condition in 1760, but Galen, Morgagni, and Vesalius had seen such cases earlier on. In 1802 the French physician J.P. Maunoir named the condition aortic dissection, and later Laennec called it dissecting aneurysm. By 1860 some eighty cases has been reported. Hypertension is the most frequent cause, but several other conditions, some inherited and some acquired, including the use of cocaine, may also cause it.

Surgical treatment became an option in 1945, when Michael DeBakey operated on the first case. Ironically, he himself developed aortic dissection at age ninety-seven and was operated for it in 2005. Since then noninvasive surgery has also become available, such as in the case of Jamie Dimon, chairman of JPMorgan, who on 3 March 2020, developed chest pain, sought medical help immediately, and had a small dissection in the wall of the aorta promptly repaired.

King George II did not fare as well. He had worn the crown of Great Britain since succeeding his father in 1727. Born and raised in Hanover, more Germanic than Britannic, he was a short irascible man with a strong German accent, a “choleric little sovereign.” As a young man he would shake his fist at his father’s courtiers and kick his coat and wig about in his rages, calling everybody thief, liar, rascal—a constant thorn in his father’s side and usually in conflict with him. In his youth he exhibited much courage, fighting under the Duke of Marlborough in several battles. During the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) he became the last monarch to lead an army into battle, fighting to defend Hanover against the French, and at one point having his horse run away and almost ending up in the enemy’s lines. He married a princess “remarkable for beauty, for cleverness, for learning, and for good temper,” who died from gangrene and sepsis after on operation for hernia. On her deathbed she entreated the king to remarry—but he famously replied that “he will have mistresses.”

Towards the end of his reign he had become hard of hearing and blind in one eye. He had never liked England, did not understand British ways, and only loved his native Hanover. But by maintaining in office Sir Robert Walpole, whom he had formerly hated, he kept England at peace for almost half a century. At Culloden in 1746 his troops suppressed the Jacobite insurrection of Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charles), putting an end to any chance of a Stuart restoration and leading to severe repression of their Scottish allies. He has always received bad press, but his preference for Hanover and lack of interest in English affairs allowed the country to develop freely and peacefully. He seems to have done better than his English-born grandson George III, whose actions helped spark the American Revolution.

References:

- William Thackeray, The Four Georges, Boston, Dana Estes and company, 1857

- Justin McCarthy. The Four Georges and William IV. Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1901.

Image credit:

- Aortic dissection – Aortendissektion (Scheme) by J. Heuser. Wikimedia.

- Histopathological image of dissecting aneurysm of thoracic aorta. Victoria blue & HE stain. Created by KGH. Wikimedia.

- Portrait of George II of Great Britain. John Shackleton. c.1755-1767. Buckingham Palace Royal collection. Accessed via Wikimedia.

Leave a Reply