Wilfred Burchett

Wilfred Burchett | |

|---|---|

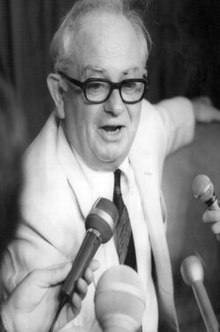

Burchett in the 1970s | |

| Born | Wilfred Graham Burchett 16 September 1911 |

| Died | 27 September 1983 (aged 72) |

| Resting place | Central Sofia Cemetery |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Spouses | Erna Lewy, née Hammer

(m. 1938; div. 1948)Vesselina (Vessa) Ossikovska

(m. 1949) |

| Children | 4 |

| Relatives | Stephanie Alexander (niece) |

Wilfred Graham Burchett (16 September 1911 – 27 September 1983) was an Australian journalist known for being the first western journalist to report from Hiroshima after the dropping of the atomic bomb, and for his reporting from "the other side" during the wars in Korea and Vietnam.

Burchett began his journalism at the start of the Second World War, during which he reported from China, Burma and Japan and covered the war in the Pacific. After the war he reported on the trials in Hungary, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and on Cambodia under Pol Pot. During the Korean war he investigated and supported claims by the North Korean government that the US had used germ warfare. He was the first western journalist to interview Yuri Gagarin after Gagarin's historic first flight into outer space (Vostok 1). He played a role in prompting the first significant Western relief to Cambodia after its liberation by Vietnam in 1979.

He was a politically engaged anti-imperialist who always placed himself amongst the people and events about whom he was reporting. His reporting antagonised both the US and Australian governments and he was effectively exiled from Australia for almost 20 years before the incoming Whitlam government granted him a new passport.

Early life[edit]

Burchett was born in Clifton Hill, Melbourne in 1911 to George Harold and Mary Jane Eveline Burchett (née Davey).[1][2] His father was a builder, a farmer, and a Methodist lay preacher with radical convictions who "imbued [Burchett] with a progressive approach to British India, the Soviet Union and republican China".[2][3] He spent his youth in the south Gippsland town of Poowong and then Ballarat, where Wilfred attended the Agricultural High School. Poverty forced him to drop out of school at fifteen and work at various odd jobs, including as a vacuum cleaner salesman and an agricultural labourer.[4] In his free time he studied foreign languages, mainly French and Russian.[2]

In 1937 Burchett left Australia for London by ship.[5] There he found work in a Jewish travel agency Palestine & Orient Lloyd Ltd which resettled Jews from Nazi Germany in British Palestine and the United States.[1] It was in this job that he met Erna Lewy, née Hammer, a Jewish refugee from Germany, and they married in 1938 in Hampstead.[1] He visited Germany in 1938 before returning to Australia with his wife in 1939.[2] After his return to Australia he wrote letters to newspapers warning against the danger of German and Japanese militarism.[2][5] After the declaration of war by England, he became sought after as "one of the last Australians to leave Germany before the war".[5]

Career as a journalist, 1940–1978[edit]

Second World War[edit]

Burchett began his career in journalism in 1940 when he obtained accreditation with the Australian Associated Press to report on the revolt against the Vichy French in the South Pacific colony of New Caledonia.[2] He recounted his experiences in his book Pacific Treasure Island: New Caledonia.[5] Historian Beverly Smith said that Pacific Treasure Island describes Burchett's view of "the way in which Australian culture and mores, as they emerged from the pioneers' experience, could develop in harmony with those of the liberated peoples in neighbouring Asia".[3]

Burchett next travelled to the then Chinese capital, Chongqing, becoming a correspondent for the London Daily Express and also writing for the Sydney Daily Telegraph. He was wounded while reporting on Britain's campaign in Burma.[2] He also covered the American advance in the Pacific under General Douglas MacArthur.[2]

Hiroshima[edit]

Burchett was in Okinawa when he heard on the radio that "the world’s first A-bomb had been dropped on a place called Hiroshima".[5] He was the first Western journalist to visit Hiroshima after the atom bomb was dropped, arriving alone by train from Tokyo on 2 September, the day of the formal surrender of Japan, after a thirty-hour train trip in breach of MacArthur's orders.[6] He was unarmed, and carrying rations for seven meals, a black umbrella and a Baby Hermes typewriter.[5][6] During his reporting, he ran into a press junket organized by Tex McCrary for promoting the United States Army Air Force and later referred to the group as "housetrained reporters" participating in a "cover-up".[7] His Morse code dispatch was printed on the front page of the Daily Express newspaper in London on 5 September 1945. Entitled "The Atomic Plague", and with the subtitle "I Write This as a Warning to the World", it began:

In Hiroshima, 30 days after the first atomic bomb destroyed the city and shook the world, people are still dying, mysteriously and horribly – people who were uninjured by the cataclysm – from an unknown something which I can only describe as atomic plague. Hiroshima does not look like a bombed city. It looks as if a monster steamroller had passed over it and squashed it out of existence. I write these facts as dispassionately as I can in the hope that they will act as a warning to the world.[5]

On this "scoop of the century", which had a worldwide impact,[6] Burchett's byline was incorrectly given as "by Peter Burchett".[8]

MacArthur had imposed restrictions on journalists' access to bombed cities, and had censored reports of the destruction caused by the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Civilian casualties were downplayed and the deadly lingering effects of radiation were dismissed.[6] The New York Times published a front-page story with the headline 'No radioactivity in Hiroshima ruin'.[9] Military censors suppressed a 25,000 word story about the bombing of Nagasaki submitted by George Weller of the Chicago Daily News.[6]

Burchett's report was the first in the Western media to mention the effects of radiation and nuclear fallout and was, therefore, a major embarrassment for the US military.[5] In response, US officials accused Burchett of being under the sway of Japanese propaganda.[6] Burchett lost his press accreditation and he was ordered to leave Japan, although this order was later withdrawn. In addition, his camera, containing photos of Hiroshima, was confiscated while he was documenting persistent illness at a Tokyo hospital. The film was sent to Washington and classified secret before being released in 1968.[10][11] US military encouraged the journalist William L. Laurence of The New York Times to write articles dismissing the reports of radiation sickness as part of Japanese efforts to undermine American morale. Laurence, who was also being paid by the US War Department, wrote the articles the US military wanted even though he was aware of the effects of radiation after observing the first atomic bomb test on 16 July 1945, and its effect on local residents and livestock.[6][12][13]

Burchett wrote about his experiences in his book, Shadows of Hiroshima.

Eastern Europe[edit]

After three years in Greece and Berlin working for the Daily Express, Burchett began reporting on Eastern Europe for The Times. He covered some of the post-war political trials in Hungary, including that of Cardinal Mindszenty in 1949, and of the communist László Rajk, who was convicted and executed the same year. Burchett described Rajk as a "Titoist spy" and a "tool of American and British intelligence".[14] Burchett praised the post-war Stalinist purges in Bulgaria: the "Bulgarian conspirators were the left arm of the Hungarian reactionary right arm".[This quote needs a citation]

In his autobiography, Burchett later admitted that he began to have doubts about the trials when one of the Bulgarians repudiated his signed confession.[15] Hungarian Tibor Méray accused Burchett of dishonesty regarding the trials and the subsequent Hungarian Revolution of 1956 which he opposed.[16]

Korean War, 1950–1953[edit]

Burchett returned to Australia in 1950 and campaigned against Robert Menzies’ bill to ban the Communist Party.[2] In 1951, Burchett travelled to the People's Republic of China as a foreign correspondent for the French communist newspaper L'Humanité. After six months in China he wrote China's Feet Unbound, which supported the new Chinese government of Mao Zedong. In July 1951, he and British journalist Alan Winnington[17] made their way to North Korea to cover the Panmunjom Peace Talks. While in Korea he reported from the Northern side for the French communist newspaper Ce soir and the American radical publication National Guardian.[2]

Burchett investigated and confirmed claims by the North Korean government that the US had used Germ warfare in the Korean War. During his investigation, he observed "clusters of flies and fleas on the snow-covered hillsides", which the North Korean military said were infected with bubonic plague. In his 1953 book about the Korean war, This Monstrous War, he wrote:

My main interest in the camps was to interview American airmen. The testimony of those who admitted to taking part in germ warfare has already been published. I talked to all of these airmen at length and on several occasions. I am convinced that the statements they made are accurate and were made of their own free will.[18]

The US military's Far Eastern Command (FEC) wanted to silence Burchett by "exfiltrating" him from North Korea but its request to the Australian government for permission, which included a $100,000 inducement (over $1,000,000 in 2022 dollars), was turned down. Instead, the FEC established a smear campaign against Burchett with the backing of the Australian government.[19] Australian journalist Denis Warner suggested Burchett had concocted the claim that the USA was engaging in germ warfare and pointed out the similarity of the allegations to a science fiction story by Jack London, a favourite author of Burchett's.[20] However, Burchett's former colleague and veteran anti-communist, Tibor Méray, confirmed Burchett's insect observation in his critical memoir On Burchett.[21] Burchett's finding was later supported by a 2010 report by al-Jazeera.[19]

Burchett visited several POW camps in North Korea, comparing one to a "luxury resort", a "holiday resort in Switzerland", which angered POWs who had been held under conditions that violated the Geneva Conventions.[22][23] Historian Gavan McCormack wrote that Burchett regretted this analogy, but said that the factual basis of the description was confirmed by POW Walker Mahurin.[24] Similarly, Tibor Méray reports a "Peace Fighter Camp" which had no fences.[25]

On 21 December 1951, Burchett achieved a major scoop by interviewing the most senior United Nations POW, US General William F. Dean and organising for photographs of Dean to be taken. The US had claimed that Dean had been killed by the North Koreans and had intended using his death as leverage in negotiations with the North Koreans. It was consequently angry that Burchett reported he was alive.[22] In his autobiography Dean entitled a chapter "My Friend Wilfred Burchett" and wrote "I like Burchett and am grateful to him". He expressed thanks for Burchett's "special kindness" in improving his conditions, communicating with his family, and giving him an "accurate" briefing on the state of the war.[23][26]

In his study of war correspondents, The First Casualty, Phillip Knightley wrote that "in Korea, the truth was that Burchett and Winnington were a better source of news than the UN information officers, and if the allied reporters did not see them they risked being beaten on stories".[27]

Moscow[edit]

In 1956, Burchett arrived in Moscow as a correspondent for the National Guardian newspaper, while also writing for the Daily Express, and, from 1960, for the Financial Times.[2] According to Robert Manne, Burchett received a monthly allowance from the Soviet authorities.[28][29] For the next six years he reported on Soviet advances in science and the rebuilding of the post-war Soviet economy. In one dispatch Burchett wrote:

"A new humanism is at work in the Soviet Union which makes that peddled in the West look shoddy, for it starts right down in the grass roots of Soviet society; its all-embracing sweep leaves behind no underprivileged".[4]

In 1961, Burchett was the first western journalist to interview Yuri Gagarin after his historic space flight. Describing Gagarin, Burchett wrote that "the first impression was of his good-natured personality; big smile -- a grin, really -- light step and an air of sunny friendliness ... His hands are incredibly hard; his eyes an almost luminous blue".[3]

China[edit]

In his 1946 book, Democracy with a Tommy Gun, Burchett wrote about his view of the coming crisis in Western imperialism in Asia. In particular he said that "the British Raj in India and the Kuomintang dictatorship (in China) represent decaying systems of government" and "immediately the war ended, subject people in the East began to rise" to take their "freedom and independence".[3]

Burchett eventually sided with China in the Sino-Soviet split. In 1963, he wrote to his father George that the Chinese were "one hundred per cent right", but asked George to keep his views confidential.[28]

In 1973, Burchett published China: The Quality of Life, with co-author Rewi Alley. In Robert Manne's view this was "a book of unconditional praise for Maoist China following the Great Leap Forward and the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution".[28]

In a 1983 interview, Burchett said he grew disillusioned with China over its position in Angola in which it was supporting the "same side as the CIA".[9]

Vietnam[edit]

In 1962, Burchett began writing on the war in Vietnam, from the North Vietnamese side.[2] Beginning in November 1963, Burchett spent six months in southern Vietnam with National Liberation Front guerrillas, staying in their fortified hamlets and travelling underground in their network of narrow tunnels.[30] When US President Kennedy increased funding for the war in Vietnam, Burchett wrote: "No peasants anywhere in the world had so many dollars per capita lavished on their extermination".[30] He described Ho Chi Minh as "the greatest man I’ve ever met, with all the modesty and simplicity that goes with human greatness".[9] He once described Saigon as "a seething cauldron in which hissed and bubbled a witches' brew of rival French and American imperialisms spiced with feudal warlordism and fascist despotism"[30] and decried the government of South Vietnam under Ngô Đình Diệm as "an Asian neo-fascism no less dangerous for world peace than...European fascism" was during the 1930s.[31]

During his time in Vietnam he had access to the North Vietnamese leadership and the South's National Liberation Front. He tried to help the British and US governments in obtaining the release of captured American airmen. In 1967, he had a significant interview with the North Vietnamese foreign minister, Nguyen Duy Trinh in which Nguyen provided the first indication that the North Vietnamese government was interested in peace talks.[19] He played a role in trying to organise informal talks during the 1968 peace talks in Paris.[2]

Bertrand Russell wrote that "If any one man is responsible for alerting Western opinion to the struggle of the people of Vietnam, it is Wilfred Burchett".[9]

Burchett published numerous books about Vietnam and the war.

Cambodia[edit]

In 1975 and 1976, Burchett sent a number of dispatches from Cambodia praising the new government of Pol Pot. In a 14 October 1976 article for The Guardian (UK), he wrote that "Cambodia has become a worker-peasant-soldier state", and, because its new constitution "guarantees that everyone has the right to work and a fair standard of living", it was, Burchett believed, "one of the most democratic and revolutionary constitutions in existence anywhere".[32] At the time, he believed his friend, former prince Norodom Sihanouk, was part of the leadership group.[33]

As relations between Cambodia and Vietnam deteriorated, and after Burchett visited refugee camps in 1978, he condemned the Khmer Rouge and they subsequently placed him on a death list.[34]

Burchett visited Phnom Penh in May 1979 and wrote in The Guardian about the desperate situation there. The Phnom Penh government drew up a list of required emergency relief which Burchett took to London, where he read it out at an all-party meeting in the House of Commons. He said that the governments in both Vietnam and Cambodia had assured him that relief would be welcome and that "a great many human beings are starving and need your help". The UK government did nothing in response to Burchett's request since the newly elected government of Margaret Thatcher had joined the US boycott of Vietnam and suspended all food aid to both Vietnam and Cambodia. However, Jim Howard, a technical officer for Oxfam was at the meeting and was moved to arrange for the first significant Western relief to Cambodia.[35]

Writing style[edit]

Greg Lockhart analysed Burchett's writing in an article in The Australian newspaper. Lockhart thought the "involved narrator" present in Burchett's writing was similar to that of Henry Lawson. He said Burchett's style fitted with the "politically engaged, social realist reportage -- the I narratives -- that swept progressive journalism in Europe and Asia in the '20s and '30s: George Orwell's Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), for instance". Lockhart said that Burchett's method of writing quickly and outside the structures of Western journalism was both a strength and a weakness of his work. Sinologist Michael Godley said that the camera verite method, which was in vogue in Beijing in 1951 when Burchett was there, may have influenced his style.[3]

Australian Government actions[edit]

Exile from Australia 1955–1972[edit]

In 1955, Burchett's British passport went missing, believed stolen, and the Australian Government refused to issue a replacement and asked the British to do the same.[36] He again requested an Australian passport in 1960 and 1965 but was denied both times. A further request in July 1968 was rejected by prime minister John Gorton.[1] For many years Burchett held a Vietnamese laissez-passer which grew so large due to the additional pages that needed to be added each time he travelled, that Burchett said he needed an attache case to carry it. While Burchett was attending a conference in Cuba, Fidel Castro learned about his passport problem, and issued him with a Cuban passport.[37] Matters came to a head in 1969 when Burchett was refused entry into Australia to attend his father's funeral. The following year his brother Clive died,[38] and Burchett flew to Brisbane in a privately chartered light plane as the Gorton government had threatened commercial airlines with steep penalties for flying Burchett into the country.[19] He was allowed entry, triggering a media sensation.[39] In 1972, an Australian passport was finally issued to Burchett by the incoming Whitlam government which said there was no evidence to justify its continued denial.[19][40] Writing in The Australian, Greg Lockhart described the previous governments' actions as "a remarkable breach of the human rights of an Australian citizen" in which it "simply exiled him for 17 years".[3]

Government attempts to prosecute Burchett[edit]

Conservative Australian governments between 1949 and 1970 tried to construct a case to prosecute Burchett but were unable to do so.

After Burchett reported from North Korea about the use of germ warfare by the Americans, the Australian government looked at charging him with treason. It sent ASIO agents to Japan and Korea to collect evidence but in early 1954, conceded it could not prosecute him.[19]

The last attempt was in 1970, when attorney-general Tom Hughes admitted to prime minister John Gorton, that the government had no evidence against him. Hughes said that a prosecution for treason under the Crimes Act "cannot be mounted unless the war is a proclaimed war and there is a proclaimed enemy", and the Australian government had not declared war in Korea and Vietnam.[3]

Australian Broadcasting Corporation[edit]

Around 1967, ABC journalist Tony Ferguson filmed an interview with Burchett in Phnom Penh. According to filmmaker David Bradbury, Ferguson said that the general manager of the ABC, Talbot Duckmanton, ordered its destruction. Bradbury's own 1981 documentary film on Burchett, Public Enemy Number One was never shown in full on Australian television because the ABC refused to buy it.[3]

ASIO[edit]

The Australian national security department, which became ASIO in 1949, opened a file on the whole Burchett family in the 1940s. Australian security was concerned by Burchett's father's interest in helping Jewish refugees in Melbourne, and his views on the Soviet Union and republican China. A document on Burchett's own file dated February 1944 noted:

"This man is a native of Poowong and his past life has been such that his activities are worth watching closely. He is an expert linguist and has travelled extensively. A comparatively young man who married a German Jewess with a grown family, he seldom misses an opportunity to speak and act against the interests of Britain and Australia".

Other documents on Burchett's file show ASIO was concerned by his scathing criticism of American imperialism.[3]

Yuri Krotkov and Jack Kane[edit]

Burchett first met Yuri Krotkov in Berlin after the second world war and they met again when Burchett moved to Moscow in 1957. Krotkov defected to Britain in the early 1960s. He had been a low-ranking KGB agent who the British passed on to the Americans.[19] In November 1969, Krotkov testified before the US Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security that Burchett had been his agent when he worked as a KGB controller. Others he named as agents and contacts included, implausibly, Jean-Paul Sartre and John Kenneth Galbraith.[41] He claimed that Burchett had proposed a "special relationship" with the Soviets at their first meeting in Berlin in 1947. Krotkov also said that Burchett had worked as an agent for both Vietnam and China and was a secret member of the Communist Party of Australia.[citation needed]

In September 1971, Democratic Labour Party leader Vince Gair accused Burchett, in the Senate, of being a KGB operative and tabled Krotkov's testimony. In November 1971, the DLP published details of Gair's speech in its pamphlet, Focus. In February 1973 Burchett filed a one-million-dollar libel suit against DLP senator Jack Kane, who was Focus's publisher.[1] In preparing his case, Kane received support from The Herald and Weekly Times, Philip Jones and Robert Menzies. Australia's military chiefs-of-staff appeared as witnesses for Kane. ASIO provided the names of Australian POWs whom Burchett had met in Korea and Kane put thirty of these on the stand. The former prisoners testified that Burchett had used threatening and insulting language against them and in some cases had been involved in their interrogations.[19][42] North Vietnamese defectors, Bui Cong Tuong and To Ming Trung, also testified at the trial, claiming that Burchett was so highly regarded in Hanoi he was known as "Comrade Soldier", a title he shared only with Lenin and Ho Chi Minh.[43]

The jury found Burchett had been defamed, but considered the Focus article a fair report of the 1971 Senate speech by Gair and therefore protected by parliamentary privilege. Costs were awarded against Burchett.[1] Burchett appealed and lost. In their 1976 judgement, the appeal court judges found that Kane's article was not a fair report of the Senate speech. The jury's verdict, however, they concluded, arose out of the failure of Burchett's lawyer to argue his client's case and was not an error of the court. It was also impractical to recall the international witnesses for a retrial.[44]

Historian Gavan McCormack has said in Burchett's defence that his only dealings with Australian POWs were "trivial incidents" in which he "helped" them.[45] With regard to other POWs, McCormack stated that their allegations were at variance with earlier statements which either explicitly cleared Burchett or blamed someone else.[46]

For his part, Tibor Méray alleged that Burchett was an undercover party member but not a KGB agent.[47]

Bukovsky archive[edit]

During his return visits to Moscow in the early 1990s, veteran dissident Vladimir Bukovsky was given access by the Russian government to classified documents from the archives of the CPSU Central Committee. Bukovsky secretly photocopied thousands of pages and in 1999 these were posted online. Among the documents were a memorandum dated 17 July 1957 and a decision dated 25 October 1957 concerning Burchett.[29][28]

The July memorandum was written by the chairman of the KGB and addressed to the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party. It mentioned that Burchett had agreed to work in Moscow on "condition" that he receive "a monetary subsidy, and also the opportunity of unpublicised collaboration in the Soviet press". The memorandum also contained a description of Burchett's background and a request for him to be paid "a one-time subsidy in the sum of 20,000 roubles and the establishment for him of a monthly subsidy in the sum of 4;000 roubles". On 25 October, the Central Committee accepted the KGB's request but reduced the monthly payment to 3;000 roubles.[28]

In 2013 Robert Manne used these documents to update "Agent of Influence: Reassessing Wilfred Burchett", his 2008 article in which he examined Burchett's relationship with a number of communist governments in Europe and Asia.[48] Manne concluded in 2013 that "Every detail in the KGB memorandum is consistent with the Washington testimony of Yuri Krotkov". Manne wrote that Krotkov "was not a liar and a perjurer, but a truth-teller".[28] Conversely, Tom Heenan, from the National Centre for Australian Studies, was not convinced by the evidence Manne quoted and wrote that, if the KGB had given money to Burchett, it had been shortchanged, since Burchett had moved away from Soviet Communism and towards the Chinese by the 1960s.[19]

Death and legacy[edit]

Burchett moved to Bulgaria in 1982 and died of cancer in Sofia the following year, aged 72.[1]

A documentary film entitled Public Enemy Number One by David Bradbury was released in 1981. The film showed how Burchett was criticised in Australia for his coverage of "the other side" in the Korean and Vietnam Wars, and posed the questions: "Can a democracy tolerate opinions it considers subversive to its national interest? How far can freedom of the press be extended in wartime?"[49]

In 1997, journalist Denis Warner wrote: "he will be remembered by many as one of the more remarkable agents of influence of the times, but by his Australian and other admirers as a folk hero".[50]

Nick Shimmin, co-editor of the book Rebel Journalism: The Writings of Wilfred Burchett said "When he saw injustice and hardship, he criticised those he believed responsible for it".[30]

In 2011 Vietnam celebrated Burchett's 100th birthday with an exhibition in the Ho Chi Minh Museum in Hanoi.[51]

Personal life[edit]

Burchett met and married his first wife Erna Lewy, a German Jewish refugee, in London and they married in 1938.[1] They had one son together.[2] They divorced in 1948, and Burchett married Vesselina (Vessa) Ossikovska, a Bulgarian communist, in December 1949 in Sofia.[1] They had a daughter and two sons.[1] His children were denied Australian citizenship at the request of Robert Menzies in 1955.[1] His son George was born in Hanoi, and grew up in Moscow and France. He lived in Hanoi and edited some of his father's writings and produced a documentary.[5]

Burchett was the uncle of chef and cookbook writer Stephanie Alexander.[52]

Bibliography[edit]

Autobiography[edit]

- Passport: An Autobiography (1969)

- At the Barricades: The Memoirs of a Rebel Journalist (1980)

- Memoirs of a Rebel Journalist : the Autobiography of Wilfred Burchett (2005) edited by Nick Shimmin and George Burchett, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, New South Wales. ISBN 0-86840-842-5

Drama[edit]

- The Changing Tide: a play based on the Hungarian spy trials (1951), World Unity Publications, Melbourne.

Works[edit]

- Pacific Treasure Island: New Caledonia: Voyage through its Land and Wealth the Story of its People and Past (1941), F.W. Cheshire Pty. Ltd., Melbourne; American reprint (1944), David McKay Co., Philadelphia.

- Bombs Over Burma (1944), F.W. Cheshire Pty. Ltd., Melbourne

- Democracy with a Tommygun (1946), Wadley & Ginn, London.

- Wingate Adventure (1944), F.W. Cheshire Pty. Ltd., Melbourne

- Warmongers Unmasked: Cold War in Germany (1950), World Unity Publications, Melbourne.

- People's Democracies (1951), World Unity Publications, Melbourne

- China's Feet Unbound (1952), World Unity Publications, Melbourne.

- This Monstrous War (1953) J. Waters, Melbourne

- (with Alan Winnington), Koje Unscreened, (1953), British-China Friendship Association.

- Mekong Upstream: A Visit to Laos and Cambodia, (1959), Seven Seas Publishers, Berlin, GDR, #306/60/59, 289p. + 2 maps

- Again Korea. New York: International Publishers. 1968. OCLC 601135697.

- (with Rewi Alley), China: The Quality of Life (1974). Pelican 1976, pbk edn.

- "The struggle for Korea's national rights". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 5 (2): 226–234. 1975. doi:10.1080/00472337508566940. ISSN 0047-2336.

- Southern Africa Stands Up: The Revolutions in Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia and South Africa (1978), Urizen Books, New York

- The China-Cambodia-Vietnam Triangle (1981), Zed Press, ISBN 0862320852, 256p.

- Shadows of Hiroshima (1983), Verso Publishers, London.

- Rebel Journalism: The Writings of Wilfred Burchett (2007) edited by Nick Shimmin and George Burchett, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-71826-4

Works on Vietnam[edit]

- North of the 17th Parallel (1957), Red River Publishing House - Hanoi.

- The Furtive War-The United States in Vietnam and Laos (1963), International Publishers - New York.

- My Visit to the Liberated Zones of South Vietnam (1964), Foreign Languages Publishing House - Hanoi.

- Vietnam: The Inside Story of a Guerrilla War (1965), International Publishers.

- Eyewitness in Vietnam (1965), published by The Daily Worker - London (UK).

- Vietnam North: A First-hand Report (1966), Lawrence & Wishart Publishers - London (UK).

- Vietnam Will Win! Why the People of South Vietnam have Already Defeated US Imperialism (1968), Monthly Review Press - New York.

- Second Indochina War : Cambodia and Laos Today (1970), Lorimer Publishing - London (UK).

- (with Prince Norodom Sihanouk), My War with the CIA: The Memoirs of Prince Norodom Sihanouk (1974) Pelican - London (UK).

- Grasshoppers and Elephants: Why Vietnam Fell (1977), Urizen Books Inc. - New York.

- Catapult to Freedom: The Survival of the Vietnamese People (1978), Quartet Publishers - London (UK).

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Heenan, Tom, "Burchett, Wilfred Graham (1911–1983)" Archived 28 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine in Australian Dictionary of Biography Online (206).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Callick, Rowan. "Wilfred Burchett". Melbourne Press Club. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lockhart, Greg (4 March 2008). "Red dog? A loaded question". The Australian. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ a b Morris, Stephen J. (1 November 1981). "A Scandalous Journalistic Career". Commentary Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Burchett, George; Shimmin, Nick, eds. (2007). Rebel journalism : the writings of Wilfred Burchett (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521718264. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Goodman, Amy; Goodman, David (4 August 2020). "Atomic Bombings at 75: Hiroshima Cover-up --- How Timesman Won a Pulitzer While on War Dept. Payroll". Consortiumnews. Consortium News. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Blume, Lesley M. M. (2020). Fallout : the Hiroshima cover-up and the reporter who revealed it to the world (First Simon & Schuster hardcover ed.). New York. p. 30. ISBN 9781982128517.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Burrell, Ian (13 October 2008). "Pilger's law: 'If it's been officially denied, then it's probably true'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

"The sub got his name wrong. Wilfred forgave him".

- ^ a b c d "The Outsiders: Wilfred Burchett". johnpilger.com. 1983. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Pilger, John (1989). Heroes (Rev. ed.). London: Pan. p. 529. ISBN 033031064X. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Goodman, Amy. The Exception to the Rulers, Verso - London, 2003 Chapter 16: Hiroshima Cover-up: How the War Department's Timesman Won a Pulitzer

- ^ Goodman, Amy and David, The Baltimore Sun, "The Hiroshima Cover-Up", 5 August 2005.

- ^ Goodman, Amy; Goodman, David (5 August 2005). "The Hiroshima cover-up". baltimoresun.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Burchett wrote a play "based on the Hungarian spy trials", entitled The Changing Tide, see Bibliography.

- ^ Wilfred Burchett, Memoirs of a Rebel Journalist : The Autobiography of Wilfred Burchett (2005), edited by Nick Shimmin and George Burchett, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, New South Wales. ISBN 0-86840-842-5, pp 323-24.

- ^ Méray 2008, pp. 113–127, pp. 146–147.

- ^ See "Alan Winnington, 1910–1983", A Compendium of Communist Biographies, Graham Stevenson's website. Archived 24 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Burchett 1953, pp. 241.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Heenan, Tom (4 September 2015). "Seventy years after Hiroshima, who was Australian war correspondent Wilfred Burchett?". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ Warner, Denis, Not Always on Horseback: An Australian Correspondent at War and Peace in Asia, 1961–1993; St Leonards: Allen and Unwin; 1997; pp. 196–197.

- ^ Méray 2008, pp. 73–76.

- ^ a b "Out in the Cold: Australia's involvement in the Korean War - Wilfred Burchett | Australian War Memorial". Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ a b Gavan McCormack, "Korea: Burchett's Thirty Years' War," in Ben Kiernan (ed.), 1986, p. 169.

- ^ Gavan McCormack, "Korea", in Ben Kiernan (ed.), 1986, p. 170.

- ^ Méray 2008, pp. 64–65.

- ^ William F Dean and William L Worden, General Dean's Story, The Viking Press, New York, 1954, pp. 239, 244.

- ^ Phillip Knightley, The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero and Myth-Maker from the Crimea to Kosovo, (revised edition), Prion, London, 2000, p. 388.

- ^ a b c d e f Manne, Robert (1 August 2013). "Wilfred Burchett and the KGB". The Monthly. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ a b Bukovsky Archives online, 25 October 1957, Request from KGB for regular financial assistance for Wilfred Burchett (5 pp) Archived 24 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. See also Russian Presidential Archives, File b2/128gs.

- ^ a b c d Doyle, Brendan (25 January 2008). "Wilfred Burchett: A one-man truth brigade". Green Left. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Burchett, Wilfred G. (1963). The Furtive War: The United States in Vietnam and Laos. New York: International Publishers. p. 104.

- ^ Joseph Poprzeczny (13 September 2008). "Books: On Burchett, by Tibor Méray". News Weekly. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ Norodom Sihanouk (with Wilfred Burchett), My War with the CIA, Penguin, 1974 reprint.

- ^ Ben Kiernan (ed.), Burchett: Reporting the Other Side of the World, 1939–1983, Quartet Books, London, 1986, pp. 265–267.

- ^ Pilger, John (1989). Heroes (Rev. ed.). London: Pan. pp. 399–400. ISBN 033031064X. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Kiernan, Ben, ed. (1986). Burchett. pp. 64–65.

- ^ Pilger, John (1983). "Wilfred Burchett". The Outsiders. Event occurs at 14:50. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Gorton, John (12 February 1970), Mr Wilfred Burchett: Correspondence, archived from the original on 24 August 2014

- ^ Ben Kiernan (ed.), Burchett, 1986, p. 72.

- ^ Ben Kiernan (ed.), Burchett, 1986, p. 74.

- ^ Ben Kiernan (ed.), Burchett, 1986, p. 296.

- ^ Denis Warner, Not Always on Horseback: An Australian Correspondent at War and Peace in Asia, 1961–1993, Allen and Unwin, St Leonards, 1997, pp. 189–193.

- ^ Denis Warner, Not Always on Horseback, 1997, pp. 142, 194.

- ^ Gavan McCormack, "Korea", in Kiernan (ed.), 1986, p. 198.

- ^ Gavan McCormack, "Korea", in Kiernan (ed.), 1986, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Gavan McCormack, "Korea", in Kiernan (ed.), 1986, pp. 190–194.

- ^ Tibor Méray, On Burchett, Callistemon Publications, Kallista, Victoria, Australia, 2008, pp. 92–93, 198, 202–203.

- ^ Robert Manne, "Agent of Influence: Reassessing Wilfred Burchett", The Monthly (Australia), June 2008 (No. 35).

- ^ Public Enemy Number One (1981) Archived 16 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine at Frontline Films

- ^ Denis Warner, Not Always on Horseback: An Australian Correspondent at War and Peace in Asia, 1961–1993, Allen and Unwin, St Leonards, 1997, p. 198.

- ^ "Hero, traitor, critic – Vietnam celebrates Burchett's centenary in pictures Archived 3 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Sydney Morning Herald, Lindsay Murdoch, 22 September 2011, p. 9.

- ^ Ridge, Veronica (26 May 2012). "Stirring passions". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 24 August 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- Heenan, Tom (2006), From Traveller to Traitor. The Life of Wilfred Burchett, Melbourne University Press - Melbourne, Victoria. ISBN 0-522-85229-7

- Heenan, Kiernan, Lockhart, Macintyre & McCormack (2008), Wilfred Burchett and Australia's Long Cold War

- Kane, Jack (1989), Exploding the Myths. The Political Memoirs of Jack Kane, Angus and Robertson - North Ryde, New South Wales. ISBN 0-207-16169-0

- Kiernan, Ben, editor (1986), Burchett: Reporting the Other Side of the World, 1939-1983, Quartet Books - London, England. ISBN 0-7043-2580-2

- McCormack, Gavan (1986), "Korea: Wilfred Burchett's Thirty Year's War", in Ben Kiernan, edited, Burchett (1986).

- Meray, Tibor (2008), On Burchett, Callistemon Publications - Kallista, Victoria. ISBN 978-0-646-47788-6

External links[edit]

- David Bradbury's 1980 documentary about Burchett Public Enemy Number One

- John Pilger interviewed Burchett as part of his 1983 series The Outsiders

- Radio National's "Media Report" discussing Memoirs of a Rebel Journalist (2007).

- Stuart Macintyre and Ben Kiernan, "Wilfred Burchett's Memoirs of a Rebel Journalist (2007) - Lessons from Hiroshima to Vietnam and Iraq"

- Wilfred Burchett's Memoirs of a Rebel Journalist (2007) - Lessons from Hiroshima to Vietnam and Iraq

- Vesselina Ossikovska-Burchett, 1919–2007, Occupation Magazine website

- Wilfred G. Burchett, People's Democracies (1951)

- Wilfred Burchett at IMDb

- 1911 births

- 1983 deaths

- 20th-century Australian journalists

- Australian communists

- Australian expatriates in the Soviet Union

- Australian expatriates in Vietnam

- Australian political journalists

- Australian reporters and correspondents

- Australian war correspondents

- Burials at Central Sofia Cemetery

- Journalists from Melbourne

- People educated at Ballarat High School

- War correspondents of the Korean War

- People from Clifton Hill, Victoria