“Wherever there’s people, there’s power,” says Fred Hampton (portrayed by Daniel Kaluuya) in the Oscar-tipped drama Judas and the Black Messiah, as he looks out at the refurbished Black Panther party office the community rebuilt on their behalf. It is not just an aphorism; it is a philosophy he lives by, having spent his life organizing within his community. The moment on film speaks to the greater movement: the people are his power. The synergy feeds, nourishes. He is a community revolutionary, receiving revolutionary love from his community.

Conceived partly by the Lucas Brothers and directed by Shaka King, Judas and the Black Messiah functions as an abridged biography of the Chicago civil rights leader Fred Hampton, told through the lens of the FBI informant and Black Panther party infiltrator William O’Neal Jr, played by Lakeith Stanfield. In the late 1960s, the party endured violent government suppression. Under the umbrella of Cointelpro, the FBI sought to prevent, neutralize and discredit a “Black Messiah” who had the potential to unify the masses. It was Hampton’s head which carried the thorny crown of equality and liberation, even prophesying his own murder for the revolution as the anti-capitalist leader murdered by a hegemonic power structure.

Intended to introduce the story of Fred Hampton to a wider audience, the film explores radical politics as an expression of love. King said of the film in a Sundance film festival Q&A: “There’s definitely a message here that demonstrates that the Black Panthers were motivated by love. Love of the people and love of each other.” When asked what he admired most about the Panthers, Kaluuya echoed their inclination toward love as inspiring to him as an actor. “They poured that love into their own community. I was really inspired by that. They would die for it. They would die to protect their own and to liberate their own,” said the British actor, recently nominated for a Golden Globe for his performance.

Born in 1948, Frederick Hampton was community justice-oriented from an early age. In elementary school, he was the captain of the Patrol Boys. In high school, he staged walkouts, protesting against racism, successfully advocated for the hiring of more black teachers and administrators and was recruited by NAACP for their suburban youth division. He continued his advocacy after his graduation into the summer of 1966 where he accompanied black children via bus to an unsegregated neighborhood where they could swim; the following year, he demonstrated for their own swimming pool, closer to the neighborhood. His efforts raised the money for the aquatic center but also resulted in his placement on the FBI’s Key Agitator List. He wouldn’t join the Black Panther party until the year after, in 1968.

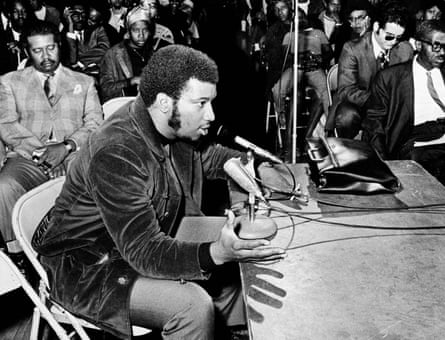

Atop his proven organizing success, Hampton was a passionate orator. Jeffrey Haas, co-founder of the People’s Law Office and author of The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther, detailed how Hampton mastered his childhood speech impediment to turn his voice into an asset. “[He] went to church with his parents and learned the cadence of the ministers at the churches,” he told the Guardian. “[He] also memorized the speeches of Dr King and Malcolm X, so that it wasn’t just an accident that his speeches had a really powerful effect, you know?

“He was like a modern-day rapper, talking quickly, a staccato between him and the other people,” said Haas, explaining how Hampton established himself as an equitable, trustworthy voice of the community. “Fred had the unique ability to speak to different audiences. He could talk to welfare mothers, to gang kids, to law students, to intellectuals, to young college students. He could bring people together.”

Haas, who met Hampton as a young lawyer and would eventually represent Hampton for the remainder of his life and in the civil suit after his death, described being enthralled by the activist’s oratory. “Fred came out and gave one of his famous speeches at the People’s church and my law partner Flint Taylor and I were there,” he said. “It was a tremendously influential speech for me to hear. I went there, thinking I was a lawyer for the movement but not necessarily of the movement. But by the time I left, and Fred had required us all to raise our right hand and say, ‘I am a revolutionary’ – words that stuck in my throat – by the end of that, I felt like I was just as committed as everyone else.”

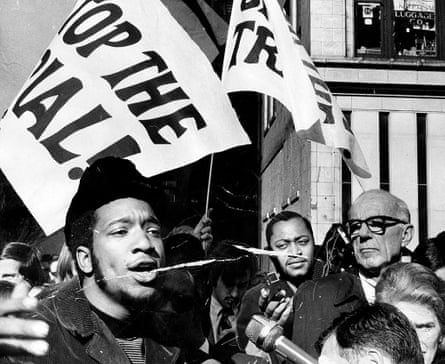

As chairman of the Chicago Black Panther party, Hampton harnessed his grassroots origins to coalesce the Black Panthers and the Puerto Rican Young Lords with the white Appalachian Young Patriots, for a union called the Rainbow Coalition. “He was able to break down these walls and bring people to the table, get them to listen to each other, respect each other and cooperate with each other … for the betterment of their overall community,” the Georgia State University professor Craig McPherson, who wrote his thesis on the civil rights figure, told the Guardian. However, it was perhaps this very act which intensified his threat level for the FBI. “[Because of the Rainbow Coalition], he represented a threat beyond just what the Panthers were,” Haas asserted.

Despite his incarceration for robbery (a spurious charge and conviction Haas believes involved collusion between the FBI and the Chicago district attorney), Hampton was still on the rise and had discussed joining the national ranks of the Black Panthers. “In the fall of 1969, Fred had gone out to the west coast and he was being considered for a position of national leadership in the Panther party,” Haas said.

Tragically, before he could do so, a 14-man police squad, operating with O’Neal’s map, equivocated testimony and an illegal search warrant, invaded Hampton’s apartment on 4 December 1969, at the behest of the Chicago district attorney, Edward Hanrahan. The officers fired into the apartment, killing Mark Clark, and continued firing, injuring several members of the party who had been unarmed. Hampton was also unarmed, having been drugged with a barbiturate by O’Neal the night prior, and did not wake during the gunfire. After firing about 100 shots into the apartment, the officers entered and fired two fatal shots into Hampton. “Almost everybody in Chicago has some sort of memory, even if it’s what their parents told them, how they remember that day. Because it really stood out in Chicago,” states Haas.

“… It was a shoot-in, and not a shoot-out. The community was outraged. It was the first time that some of the black politicians who had been very loyal to [Mayor] Daley actually spoke out against the police and against what had happened,” Haas continued. “His office saw this as a political opportunity to raid a Panther office and go in with guns blazing, [so] that he would get credit for it. The fact is, the black community, while they were divided around the Panthers … didn’t accept that a young black leader would be killed in his bed at four in the morning.” Haas noted the fear and anger of the black citizens: “It was frightening to people. If he could be killed in bed by the prosecutor, then who was safe?”

Chairman Fred Hampton was only 21 at the time of his violent death, a short lifespan which seems incongruent to his lengthy accomplishments. His assassination, by some, is attributed to his growing influence. Others suggest it was predicated on the strength and potential of his Rainbow Coalition. McPherson said, “They were seeing his successes and it scared the establishment. It scared white America. It scared the FBI, J Edgar Hoover. It scared them.”

“[The government] had nothing on him. They could not get anything on him … They were not going to get him through scandal, so the alternative they turned to was assassination,” McPherson deduced.

Publicly, the FBI denied their involvement but J Edgar Hoover, the then head of the agency, was heavily invested in the murder of Hampton, authorizing bonuses for Agent Roy Mitchell and O’Neal, as exposed in newly released documents. Though their political beliefs intuited Hoover’s probable culpability, it wasn’t until Cointelpro was made public that the conspiracy’s depth was made clear to the Black Panthers. Nevertheless, the subsequent civil case alleging conspiracy was fraught with obstruction, due to the secretive nature of the FBI. “In fact, there were two conspiracies,” Haas recounts. “One was to murder Fred and destroy the Panthers, the other one was to cover up what happened …”

Haas recalled the day he and his law partner Flint Taylor won the arduous trial years later. “I asked [Hampton’s mother] Iberia [after the court case], ‘What do you think?’ And she said, ‘They got away with murder,’” he said. Despite the apparent injustice, the assassinations of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark crucially shifted Chicago politics. It cast a poor light on Hanrahan from which he never recovered politically, and the handpicked successor to Mayor Daley would lose to Harold Washington, Chicago’s first black mayor.

Hampton’s accomplishments in activism are rarely discussed in the history books. He seems almost a hidden figure, a forgotten martyr canonized only by activists and scholars. While rappers like Kendrick Lamar and Jay-Z invoke his name in rhymes, his life is not taught. Even King, the director of the film, admitted knowing more about the circumstances regarding his death than his life. “He belongs in the grouping with Dr King, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, and I believe he should be getting more recognition,” McPherson declared, theorizing Hampton’s local activism didn’t provide a large enough stage. “Fred Hampton, in his 21 years, did not get to move beyond Chicago very much … He didn’t get a chance to have a lot of the exposure.”

Regardless, Haas insists Hampton deserves his recognition. “The story of Fred Hampton should be taught in the schools of Chicago. There should be some kind of memorial, a symbol of what happened on that day,” the civil rights lawyer expresses. “I think there should be public recognition and acknowledgment of what happened. And an apology from the city.” Indeed, where Hampton’s house once stood, there is a different housing development but no mention of the assassinated activists who lived and tragically died there. In 2006, there was discussion to rename the street after Hampton but nothing materialized following intense resistance from Chicago law enforcement. In fact, the only remaining public monument to his legacy remains the Fred Hampton Maywood Aquatic center. But the evanescence served as motivation for King to create Judas and the Black Messiah, calling the movie “an incredibly clever vessel to introduce a history that has been buried in this country to a very wide audience”.

Even without the movie, Haas declared his experience with Hampton and the Chicago Black Panther party “the most dramatic and life-changing thing that I had [experienced], being that close, seeing it that close,” and maintains Hampton’s experiences are just as salient as ever, from which one can draw parallels to the infiltration and espionage at Standing Rock, and of course, the Black Lives Matter movement. King also draws the thread between past and present treatment of political voices. “The history of this country and government in terms of repressing voices of dissent, history and present – [the government] still engages in these same practices today,” King said.

Hampton, though his life was tragically cut short, continues to spread his words of revolution and equality, 51 years after his murder, prescient in these uncertain times. “He lived as he spoke,” Haas said. “He’s a symbol of resistance, of rebellion, of making demands of the government.” McPherson echoed a similar sentiment about Hampton’s foreknowledge, saying: “We could use Fred Hampton today in America.”

Judas and the Black Messiah is released in cinemas and on HBO Max on 12 February and in the UK on 26 February