After President Joe Biden proposed his $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief plan, a group of 10 relatively moderate Senate Republicans decided to test his desire for bipartisanship by making a significantly lower counteroffer. The clique, led by Maine’s Susan Collins, produced a $618 billion proposal, with stingier checks to households, lower unemployment benefits, and no aid to state and local governments.

Democrats have dismissed the GOP’s bid as insufficient, and with Biden’s support, they’ve begun taking the steps necessary to pass relief legislation on a party-line vote, via the process known as budget reconciliation. “Republicans want to climb out of a 13-foot hole with a 6-foot ladder,” a senior aide in the Senate told CNN. “We don’t have time to wait for them to get serious about the problem.”

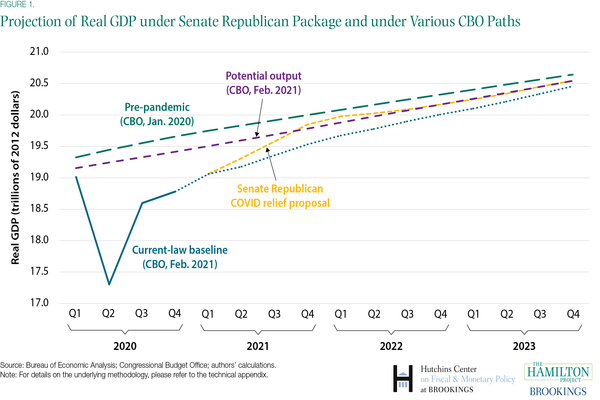

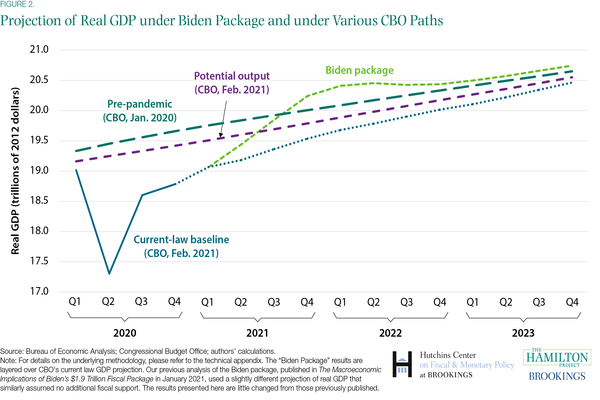

That assessment might be a tiny bit too harsh, but it is directionally correct. Under the GOP’s proposal, the United States would simply not return to the economic growth path it was on prior to the pandemic. Under Biden’s proposal, in contrast, it would. One plan is large enough to lift America fully out of its ditch; the other is not.

That finding comes from a new report this week by the Brookings Institution. The analysis concludes that if Congress were to settle for the GOP’s plan, the economy would remain 0.8 percent below its pre-COVID trend come the end of 2022.

Biden’s plan doesn’t fall short in this respect. According to the analysis, it would temporarily push the economy above the growth trajectory it was on before the economy went into hibernation last March, which would help make up for some of the lost activity.

One subtle but important point to keep in mind is that the aid package Democrats are crafting at the moment is not primarily designed to fill the coronavirus-shaped gap in our gross domestic product. Ditto for the Republican counteroffer. Rather, both bills are meant to provide Americans with relief as they continue to ride out the pandemic while vaccines are distributed—it’s meant to be a life jacket, not a whole repaired ship. You don’t have to look at an economic forecast to conclude that the GOP plan probably falls short on that front, given that its relatively scrooge-ish contours.

All that said, it would certainly be a good thing if the final relief legislation put us back on a path to full recovery. And the fact that the GOP plan undershoots that goal is a strong sign that it won’t help to all of those who need it, either. After all, if there’s a hole left over in the economy, that means some families are almost certainly trapped in it.

The Brookings analysis offers one finding that, on its face, seems favorable to the moderate-Republican plan. It suggests that their package would be large enough to return the country to its so-called “potential output“ by the end of 2021. In theory, this is supposed to be the economy’s speed limit—the fastest it can grow over the long term without causing inflation to spike and eat up the gains (economists call this “overheating”). The country can cruise above that line for a while, but not forever; at some point, the thinking goes, unemployment will fall so low that employers won’t be able to find many new workers to hire, and businesses will max out their capacity to produce more stuff. As a result, pouring more money into the economy will just make a trip to Target or Whole Foods more expensive.

Biden’s plan would lead the economy to overshoot its potential, according to the Brookings team. Inflation would consequently rise, making the government’s relief spending less effective. This has led some centrist critics, such as the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, to suggest that Biden’s plan may be too large, and that some of its aid dollars would likely add to the debt without significantly improving the economy. On Thursday, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers suggested, somewhat melodramatically, that “there is a chance that macroeconomic stimulus on a scale closer to World War II levels than normal recession levels will set off inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation, with consequences for the value of the dollar and financial stability.“ At least some conservative-leaning economists, like the University of Georgia’s Jeffrey Dorfman, have gone so far as to argue that the Republican plan may actually be good enough, since it could push us back to our so-called potential. The “it’s too big” brigade isn’t dominating the conversation by any means, but it’s piping up.

The problem with this line of thinking is that nobody actually knows what our “potential output“ really is. We’re talking about a threshold that exists in theory, but can’t be measured in real time. Economists try to estimate it based on how many Americans they think are capable of working, and how productive they can be. But even the most trusted experts often produce results that don’t pass the smell test. The Brookings team relies on estimates from the Congressional Budget Office, for instance, which believes that the economy was already firing above its potential in late 2019. That’s almost certainly not the case—the Federal Reserve cut interest rates that October because it was worried the economy was cooling, rather than overheating—and suggests they’re lowballing how much room we have to grow in the future.

Even if Democrats accidentally do go overboard, the consequences just aren’t worth losing sleep over. Worse comes to worst, inflation might jump a bit higher than Americans would like at some point down the line, and the Federal Reserve may have to raise interest rates a bit to nip it at the cost of some growth. (For now, the central bank’s leaders have said they would welcome somewhat higher inflation, which even before the crisis had been too low for years.) There’s no particular reason to think we’d see an out-of-control spiral of rising prices as Summers seems to fret, which is maybe why he barely tries to explain how it would happen.

Is it conceivable Biden’s plan is a little oversized, compared to what we strictly need from a macroeconomic perspective? Maybe. But as Powell has argued, the biggest danger to the economy right now is that we might do too little, not too much. The Biden plan doesn’t take that risk; the GOP plan most certainly does.

Update, Feb. 5, 2021: This post has been updated to dunk on Larry Summers.