Spirituality as Method in Anthropology and Sociology

It’s been there all along

The New Mindscape #T1–6.

Spirituality in the development of anthropology

In the history of anthropology, in the late 19th to early 20th centuries, when anthropology was becoming an academic discipline, it focused on studying the origin of humanity and “primitive” human beings.

Anthropology has rarely studied “spirituality” as such, but, broadly speaking, “spiritual” is often a catch-all term for all those ways of thinking, practices and ontologies excluded by modern Western rationality and materialism. Pre-modern, “savage”, “primitive” or non-Western cultures and cosmologies are full of “spiritual” ideas and practices. Anthropologists have been at the forefront of studying these cultures and cosmologies.

As European powers engaged in colonizing the rest of the world, they discovered many societies and cultures that were very different from the modern, industrial West. Thus, anthropology strived to build a holistic picture of humanity including the so-called primitive people, charting their cultures, lifestyles, ways of being, and so on.

One example was Lucien Levy-Bruhl, one of the early French anthropologists, who wrote several books on what he called the “primitive mentality” [1]. He made a dichotomy between the rational, modern mentality, and the primitive, non-rational (or perhaps, irrational or non-logical) mentality. The distinction was that the modern human being is rational, while the primitive human has a completely different mind, which he called “mystic participation.” He then tried to understand how mystic participation worked. While the assumption was that the modern mind tries to overcome mystic participation, it is still a condition of our minds. He tried to understand the mechanism of mystic participation, showing that it had its own logic, and wasn’t stupid or ridiculous, as most Europeans thought.

By the 1950s, anthropology was moving forward under anthropologists like Claude Levi-Strauss, who wrote the book The Savage Mind [2]. He built on Lévi-Bruhl’s dichotomy, but he made a difference. Although he contrasted the ‘savage mind’ with the ‘civilized mind,’ he believed that all humans have both of these mindsets. Then, he continued to study the systems of knowledge in the so-called primitive societies, showing that they were as complex and sophisticated as modern knowledge, but with a different logic. Therefore, under Levy-Bruhl, the non-rational, i.e the “spiritual” was broadly seen as backward and primitive, while under Levi-Strauss, it was reformulated as a different form of rationality, a universal structure of the human mind, which was positively valued since we all have it. This reflects the evolution of anthropology during the mid 20th century, as it started to question the racism of its origins and valorised the societies that it studied.

In contemporary anthropology, figures such as Philippe Descola, Lévi-Strauss’s disciple, ushered in the ‘ontological turn’ in anthropology. This means that anthropology is no longer just studying the beliefs or systems of representations of other cultures, but trying to understand how different cultures understand the way the world is made — that is, inquiring about the constituents of the world. Descola, for example, drew up a typology of four different types of ontologies, which include naturalism, animism, analogism and totemism [3]. In different societies and cultures around the world, we will find expressions or combinations of these four ontologies. According to this scheme, each of the four types of ontology has its own independent logic, which is as rational and plausible as the others, and they all have deep intellectual insights to offer.

This leads us into a period of ‘ontological pluralism’ in which non-Western and non-secular cultures and peoples become equal intellectual partners. The ways that the universe is understood differently are not beliefs to be described but ideas to be engaged intellectually and adopted when they can provide intellectual insights. A critical implication of the ontological turn in anthropology is that the ideas of different cultures can become sources of anthropological theory.

Another important figure in the ontological turn is Bruno Latour. Latour, perhaps, goes farther than any other in making a radical equivalency between different ontologies. Latour wrote a book and developed an intellectual agenda to show that “we have never been modern” [4]. This takes us back to Levi-Strauss’ idea that the non-modern has always been an integral part of our life. We have never been completely modern, and we should accept that.

Bruno Latour went so far as to claim that there is no division between science and religion. We have never been modern, and the division between science and religion is artificial. He said in his book Re-Assembling the Social, that we should take literally the claims of the old lady who claims that God is talking to her [5]. Latour thus proposes that we take these religious claims absolutely literally and see where they take us. This doesn’t mean that we believe in any and all religious claims — but we take them seriously, and see where they take us.

Now we take different cultures and ontologies very seriously, with respect. We learn from them and even take them as our intellectual equals, which has profound implications. The discipline of anthropology may not have fully taken the measure of that implication, which is that all of these cultures, except for the modern West, are non-secular. In other words, they have ontologies which are non-materialist, in which people deal with spiritual beings and powers. If we really want to take them seriously and overcome the inherent racism at the origins of anthropology, then we have to take the spiritual, non-secular ideas, and ontologies of these different societies seriously, by engaging them as equal intellectual partners.

If we simply say, “I can really respect those people who consider that trees or that animals have spirits,” it is nice to describe our respect. But it remains problematic if what we mean is, “I respect you because you are different, and because you are so different I will not learn from you”. Can we actually learn from them? Can we take their ideas seriously? I think there are very profound implications here, and this is one thing that I want to explore.

Spirituality in the development of sociology

Now let’s move on to the sociological tradition. The sociological tradition was built on the study of modern Western societies, as opposed to non-Western cultures. But I consider that the critical foundations of sociology are inseparable from spiritual methodologies, and I think the implications of this should be more clearly thought of in sociology.

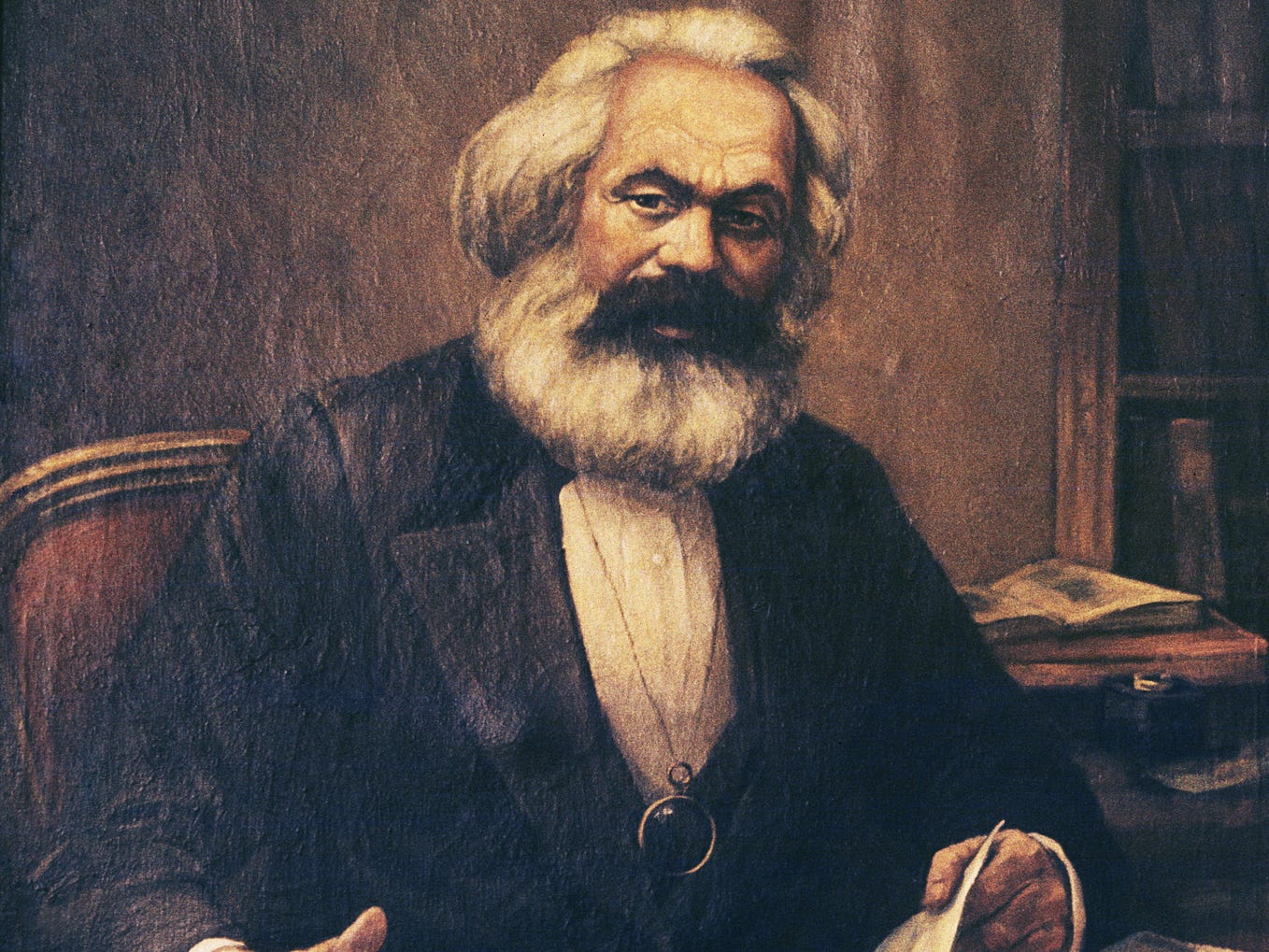

Let us look at some of the towering figures of sociology, starting with Karl Marx. Marxism is based on a critical analysis of the structures of society, and this analysis aims at creating the conditions for the liberation of humanity from oppression, leading to a communist future. Marxism claims to be materialist, but the vision that underlies the critique is actually spiritual. A world in which everybody is equal, loving, and compassionate to each other, free from oppression, injustice, and exploitation — this world has never existed in the material world. It is an imagination of an ideal, derived from religious visions of ‘heaven on earth’ and life in heaven. It is that spiritual yearning for an ideal world which motivates people to imagine a better world, to strive to build such a world. When you locate yourself within the imagination of that spiritual world, you can turn back and look at the material world today, and critique the injustice that exists in the structures of society. Thus, my argument is that Marxism is rooted in a spiritual yearning, and the Marxist critique of injustice and domination comes from situating oneself in a transcendental, spiritual location.

The Marxist would respond that Marxism is based on a materialist ontology, and denies the existence of any spiritual reality. But Marxism is not only a description — it prescribes a course of action, to build a just world. If you take a purely materialist approach, you cannot change anything because your consciousness can only reflect material reality as it is, rather than reality as it could be. The orthodox Marxist view is that consciousness is a reflection of the material world. According to Marx, the way the material world is organized is bad. It’s oppressive. Wherefrom, then, comes the desire to change the material world? Your imagination of a better world is not a material thing. It is, by definition, not a pure reflection of the material world. Your consciousness thinks of something different, not the same thing that is reflected in your mind. If you are motivated to do something to change it, that power of motivation does not come from the material world but from somewhere else. Then where does it come from? People have the motivation to improve their own personal life, yet they want to create a world that is better not just for themselves, but also better for everyone. Where does that vision come from? Where does the power to do something for that vision come from? That vision has no material existence. So actually, Marxism is about following something that does not exist and is immaterial. And yet, in following this immaterial thing, Marxists have been able to bring about huge changes in the material social world.

Now let’s consider another great founding figure of sociology, Max Weber. Weber wanted to conduct a comparative sociology of spirituality, religion, and social change. His famous work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, is a study of Protestant spirituality[6]. How does a certain form of Protestant spirituality lead people to act in a distinct way? For instance, Weber talked about the social implications of “this-worldly asceticism” and “other-worldly asceticism,” which are different forms of spirituality — different ways of working out the tensions between spiritual ideals and the reality of social life. Weber also looked at religion in China, India, etc. In each of the studies that he conducted, he examined how spiritual ideas and dispositions lead people to live their lives differently, thereby creating very different types of societies. He also talked about the routinization of charisma in religion, and how different forms of spirituality factor into different types of social authority. These questions touch on the relationships between spirituality, institutional religion, and social power. How to institutionalize? How do religions emerge out of this? How do they transform spirituality and so on? Weber’s work can be re-read as a study of spirituality and its relationships with society.

One of Weber’s overriding concern was the notion of disenchantment — the “iron cage” of modernity. Weber was very pessimistic about disenchantment: the world is becoming this iron cage, and there is nothing you could do about it. But the pessimism that exists in Weber is a kind of sense of disappointment. The iron cage is a negative metaphor. But why do you dislike the iron cage of modernity? Because there is something else that you really like, that you wish were not like an iron cage. What is the position from which you see the “iron cage” as something negative? It is from a transcendental, spiritual position — an imagined location in which humans are deeply connected to each other and to the world. Now, given that my argument is that we create the world out of our imagination, should we not enhance that imagination, in order to create a better world?

Now let’s consider the Durkheimian tradition, which I associate myself with more than any other tradition in sociology. Durkheim looked at the religious and sacred foundations of society in his book, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life [7]. For him, society comes into being via religious rituals. It doesn’t matter if the society considers itself religious or not — all societies, including modern societies, have this basic religious foundation. If we want to understand life in society, we have to understand religious life. Durkheim even wondered how the future of society would evolve. He talked about a future “religion of the human being” in which he saw the modern world becoming more and more cosmopolitan, and along with it there would be a new kind of religion — a religion of a cosmopolitan humanity. This part of Durkheim’s work has not been well developed or discussed. But in the Durkheimian sociological tradition, one cannot avoid thinking about the religious dimension of how society is constructing itself today.

Now let’s look at one of the more recent great figures of sociology: initially a philosopher, now considered one of the greatest social theorists, Michel Foucault. What is interesting here is that Foucault is perhaps one of the greatest theoreticians on spirituality. His discussion of spirituality grew out of his books on sexuality. He developed the notion of the “care of the self”, which is actually a study of Greek spirituality [8]. His later books, which have only recently been translated into English, are on the “hermeneutics of the subject” [9]. This is a very explicit and detailed study of Greek spirituality, in which Foucault defined spirituality as a form of knowledge in which knowing requires you to change yourself. And as we could see, toward the end of his life, Foucault was increasingly interested in this. He was not studying spirituality only as an external observer, but he also increasingly advocated practicing this kind of spirituality, which he saw, drawing on his study of the Greeks, as an aesthetic construction of your life. (For more on Foucault and spirituality, see my essay Why Western Philosophy Forgot about Greek Spirituality, and How Foucault Retrieved it.)

It’s important to look a little bit more into the spiritual undercurrents that underlie much of sociological theory. Now, there are also some implications here. Regarding critical sociology: what defines critical sociology is that it critically unpacks the possibly oppressive and unjust ways in which society has been constructed. But from which position can we take such a critical perspective? You can only take such a critical perspective from a position of an imaginary non-oppressive society — from the position of an imaginary human being who does not oppress nor dominate others. Who is this imaginary human being? This is a just, compassionate, loving human being who wants to create a better world. What are the sources of this justice, this love, and this compassion? Here is where I think we need to start asking ourselves spiritual questions: what is the source of the alternative to an unjust, dominating social structure?

Now we have two choices. Either we claim that human beings are only and always dominating and oppressive, in which case our critical analysis is disempowering, because we constantly assert that the contest for power is the only way in which human beings can behave. This means that our critique reinforces the structures of domination, because we are telling people that you cannot be other than a domineering, oppressive animal.

Choice number two is to say we have these dominating structures in society, but that as human beings we are capable of something different. What is the source of that capability? Is the source of that capability to be found in the dominating structure of society? Or is it somewhere else? This is a very fundamental question for critical sociology.

Conclusion

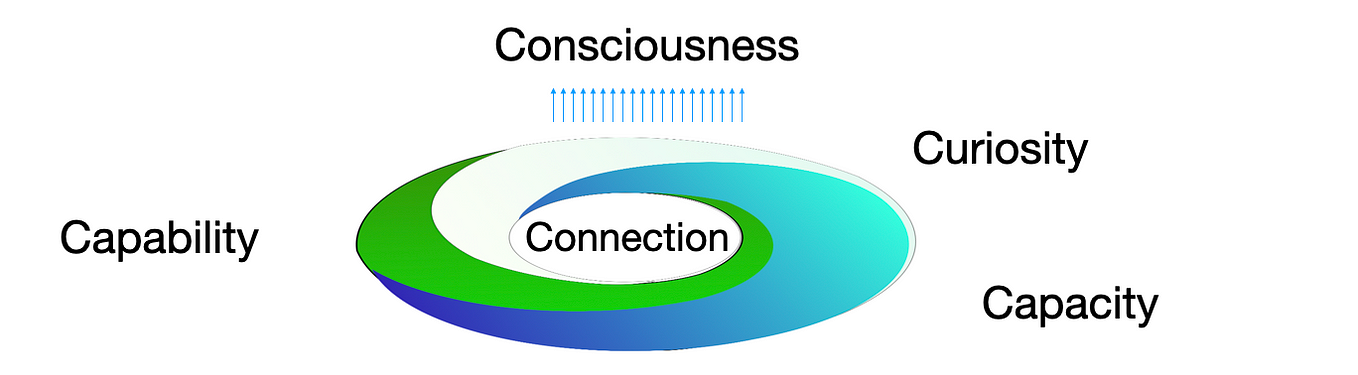

Taking a critical sociological and anthropological perspective, we see spirituality as something that is social. That means that it is something that is transformed by social life, and also the means by which we can transform social life. This is very different from individualistic understandings of spirituality. The other important thing though, is that spirituality can only be learned through a combination of theory and practice. As Foucault himself said, spirituality is knowledge that can only be gained through the transformation of the knower. That is why it is methodologically important that investigation of spirituality needs to include participant observation. For example, using an anthropological methodology, you need to participate and practice because only through the practice can you gain the knowledge.

This is an approach to spirituality which is rooted not only in sociological and anthropological theory, but also enriched and rooted in practice. How does that work? The New Mindscape is part of an exploration or experimentation of where that would go. Through this talk I have tried to sketch some of the elements to make a practically and socially engaged approach to spirituality, grounded in critical, anthropological, and sociological knowledge.

One could object from the above that the “spirituality” I speak of is vague, and even may introduce an unnecessary matter/spirit dualism. Perhaps. But modern dualism establishes a matter/spirit dichotomy in order to exclude one of the terms. It is thus necessary to retrieve the hidden or excluded term; and only then will it be possible to uncover new or forgotten connections that overcome the duality, and establish a new unity or synthesis.

This essay and the New Mindscape Medium series are brought to you by the University of Hong Kong’s Common Core Curriculum Course CCHU9014 Spirituality, Religion and Social Change, with the support of the Asian Religious Connections research cluster of the Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences.

References:

[1]Lucien Lévi-Bruhl, Primitive Mentality. Originally published in French in 1923, multiple English editions available.

[2] Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind. Originally published in French in 1962, multiple English editions available.

[3] Philippe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture. University of Chicago Press, 2013.

[4] Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern. Harvard University Press, 1993.

[5] Bruno Latour, Re-Assembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford University Press, 2007.

[6] Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Originally published in German in 1905; multiple English editions available.

[7] Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Originally published in French in 1912; multiple English editions available.

[8] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, vol. 3: The Care of the Self. Vintage Books, 1988.

[9] Michel Foucault, The Hermeneutics of the Subject: Lectures at the College de France, 1981–82. English edition: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005.