THE end of the eighteenth century was a period of disillusioned expansionists and so the colonies separated into new and distinct communities, with distinctive ideas and interests and even modes of speech. As they grew they strained more and more at the feeble and uncertain link of shipping that had joined them. Weak trading posts in the wilderness, like those of France in Canada, or trading establishments in great alien communities, like those of Britain in India, might well cling for bare existence to the nation which gave them support and a reason for their existence.

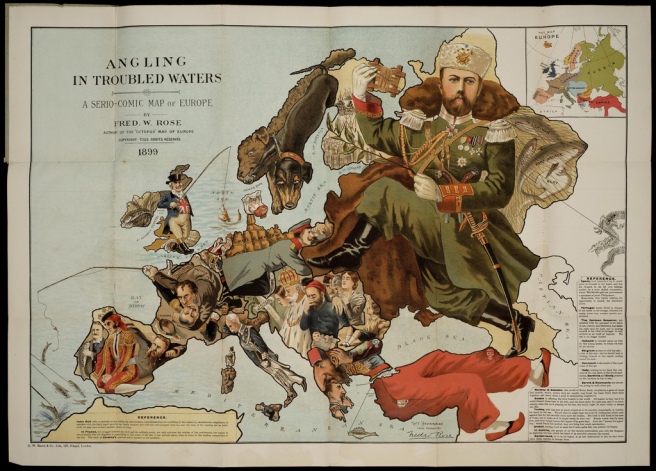

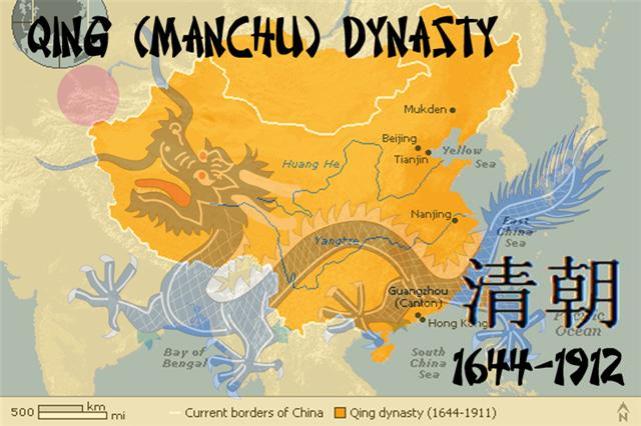

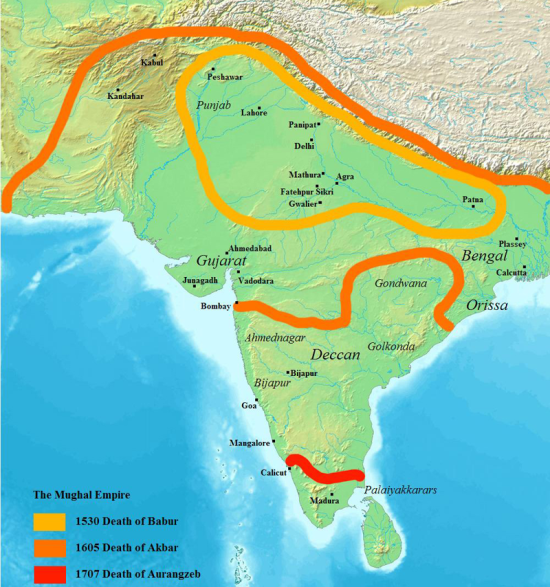

The sketchy great European “empires” outside of Europe that had figured so bravely in the maps of the middle 18th century, had shrunken to very small dimensions. Only the Russian sprawled as large as ever across Asia. The British Empire consisted of the lake regions of Canada, and a great  hinterland of wilderness in which the only settlements were the stations of the Hudson Bay Company, about a third of the Indian peninsula, under the rule of the East India Company, the coast districts of the Cape of Good Hope inhabited by blacks and rebellious Dutch settlers; a few trading stations on the coast of West Africa, and, on the other side of the world, a dump for convicts in Australia.

hinterland of wilderness in which the only settlements were the stations of the Hudson Bay Company, about a third of the Indian peninsula, under the rule of the East India Company, the coast districts of the Cape of Good Hope inhabited by blacks and rebellious Dutch settlers; a few trading stations on the coast of West Africa, and, on the other side of the world, a dump for convicts in Australia.

“A new consciousness seems to have come upon us – the consciousness of strength – and with it a new appetite, the yearning to show our strength … Ambition, interest, land hunger, pride, the mere joy of fighting, whatever it may be, we are animated by a new sensation. We are face to face with a strange destiny. The taste of Empire is in the mouth of the people even as the taste of blood in the jungle.”

Editorial, Washington Post, 1898

“God has not been preparing the English speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing but vain and idle self-admiration. No, He has made us adept in government that we may administer government among savage and senile peoples – He has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the redemption of the world.”

Senator Albert J. Beveridge, 1900

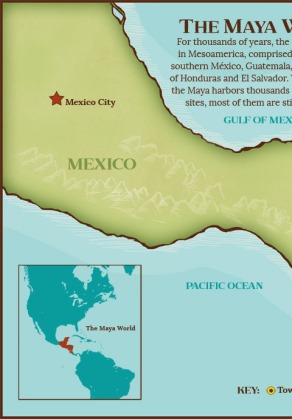

From the 1870’s through 1914, both the US and the major European powers embarked upon an unprecedented era of imperialist foreign policy. Such policies were evolutionary given the fact that the U.S. government had used the policies of Manifest Destiny to expand its empire for decades. During this period, “the taste of Empire” was ‘in the mouth of the people’. Thereafter, imperialism had three goals:

- to gain island possessions, most of which were already quite populated;

- to use the new territories not for settlement, but rather as naval bases, trading outposts, and commercial centers on major trade routes; and

- to think of the new territories as colonies rather than states-in-the-making.

By the end of the Spanish American War, the US had become a global colonial power. It now had an island empire stretching from the Caribbean to the Pacific – Puerto Rico, Philippines, Guam, Hawaii, Wake Island [annexed 1898], and Samoa [1899.]

Americans paid a high price for its new empire: making new enemies by fighting wars in Cuba and the Philippines that overturned popular rebellions, killing large numbers of the military and civilian populations, and over-riding the wishes of the majority populations; Americans occupied and annexed Hawaii and Samoa without consulting with the Hawaiians and Samoans. Americans were divided in regard to late 19th Century imperialist policies – while many supported these policies, many others were quite vocal in their opposition. Americans failed to define the relationship between political and economic liberty.

” The Philippines are ours forever…. and just beyond the Philippines are China’s illimitable markets.. The Pacific Ocean is our Ocean.”

Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana.

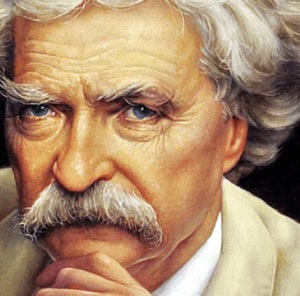

Mark Twain was neither an anarchist nor a radical. By 1900, at sixty-five, he was a world- acclaimed writer of funny-serious-American-to-the-bone stories. He watched the United States and other Western countries go about the world and wrote in the New York Herald as the century began:

“I bring you the stately matron named Christendom, returning bedraggled, besmirched, and dishonoured from pirate raids in Kiao-Chou, Manchuria, South Africa, and the Philippines, with her soul full of meanness, her pocket full of boodle, and her mouth full of pious hypocrisies.”

He commented on the Philippine war:

We have pacified some thousands of the islanders and buried them; destroyed their fields; burned their villages, and turned their widows and orphans out-of-doors; furnished heartbreak by exile to some dozens of disagreeable patriots; subjugated the remaining ten millions by Benevolent Assimilation, which is the pious new name of the musket; we have acquired property in the three hundred concubines and other slaves of our business partner, the Sultan of Sulu, and hoisted our protecting flag over that swag. And so, by these Providences of God — and the phrase is the government’s, not mine — we are a World Power.

In Greece, which had been a right-wing monarchy and dictatorship before the war, a popular left-wing National Liberation Front [the EAM] was put down by a British army of intervention immediately after the war and a right-wing dictatorship was restored. When opponents of the regime were jailed, and trade union leaders removed, a left-wing guerrilla movement began to grow against the regime. Great Britain said it could not handle the rebellion, and asked the United States to come in. As a State Department officer said later:

“Great Britain had ……. handed the job of world leadership . . . to the United States.”

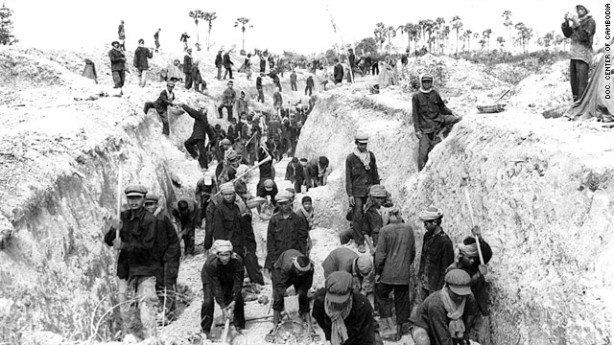

The Greek rebels were getting some aid from Yugoslavia, but no aid from the Soviet Union, which during the war had promised Churchill a free hand in Greece if he would give the Soviet Union its way in Rumania, Poland and Bulgaria. The Soviet Union, like the United States, did not seem to be willing to help revolutions it could not control. The US moved into the Greek civil war, not with soldiers, but with weapons and military advisers. 74,000 tons of military equipment were sent to the right-wing government in Athens, including artillery, dive bombers, and stocks of napalm. Two hundred and fifty army officers advised the Greek army in the field. forcibly removing thousands of Greeks from their homes in the countryside, to try to isolate the guerrillas, to remove the source of their support. With that aid, the rebellion was defeated by 1949. US economic and military aid continued to the Greek government. Investment capital from Esso, Dow Chemical, Chrysler, and other US corporations flowed into Greece. But illiteracy, poverty, and starvation remained widespread there, with the country in the hands of “a particularly brutal and backward military dictatorship.” In effect Greece became a warm up for Vietnam a few years later.

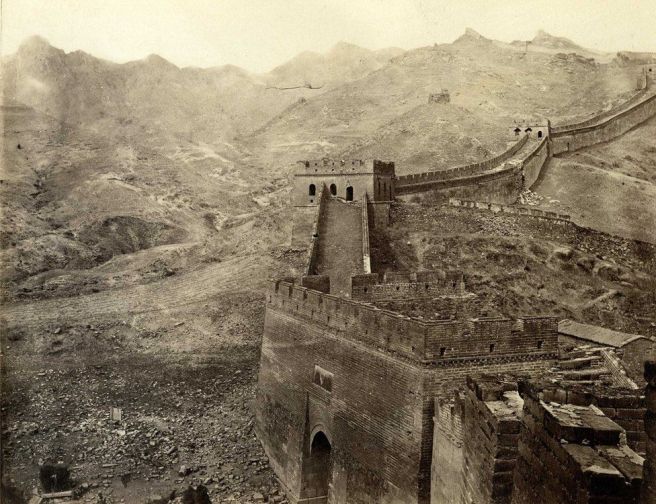

In China, a revolution was already under way when World War II ended, led by a Communist movement with enormous mass support. A Red Army, which had fought against the Japanese, now fought to oust the corrupt dictatorship of Chiang Kai-shek, which was supported by the U. S. In 1949, Chinese Communist forces moved into Peking, the civil war was over, and China was in the hands of a revolutionary movement, the closest thing, in the long history of that ancient country, to a people’s government, independent of outside control.

Korea, occupied by Japan for thirty-five years, was liberated from Japan after World War II and divided into North Korea, a socialist dictatorship, part of the Soviet sphere of influence, and South Korea, a right-wing dictatorship, in the American sphere. There had been threats back and forth between the two Koreas, and when North Korean armies moved southward across the 38th parallel in an invasion of South Korea, the United Nations, dominated by the United States, asked its members to help “repel the armed attack.” The U.S response was to reduce Korea, North and South, to a shambles, in three years of bombing and shelling.

Two weeks after presenting to the country the Truman Doctrine for Greece and Turkey, Truman issued Executive Order 9835, initiating a program to search out any “infiltration of disloyal persons” in the U.S. government. Some 6.6 million persons were investigated. Not a single case of espionage was uncovered, though about 500 persons were dismissed in dubious cases of “questionable loyalty.” All of this was conducted with secret evidence, prejudiced informers, and neither judge nor jury.

World events right after the war made it easier to build up public support for the anti-Communist crusade. In 1948, the Communist party in Czechoslovakia ousted non-Communists from the government and established their own rule. The Soviet Union that year blockaded Berlin forcing the US to airlift supplies into Berlin. In 1949, there was the Communist victory in China, and the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb. These were all portrayed as signs of a world Communist conspiracy. But just as disturbing to the American government, was the upsurge all over the world of colonial peoples demanding independence. Revolutionary movements were growing, in Indochina against the French; in Indonesia against the Dutch; in the Philippines, armed rebellion against the United States.

By 1962, based on a series of invented scares about Soviet military build-ups, a false ‘bomber gap’ and a false ‘missile gap,’ the US had overwhelming nuclear superiority. The Soviet Union was obviously behind but the US budget kept mounting, the hysteria kept growing, the profits of corporations getting defense contracts multiplied, and employment and wages moved ahead just enough to keep a substantial number of Americans dependent on war industries for their living. By 1970, the US military budget was $80 billion and the corporations involved in military production were making fortunes. Two-thirds of the $40 billion spent on weapons systems was going to twelve or fifteen giant industrial corporations, whose main reason for existence was to fulfil government military contracts. A Senate report showed that the one hundred largest defense contractors, who held 67.4 percent of the military contracts, employed more than two thousand former high-ranking officers of the military.

The Marshall Plan of 1948, which gave $16 billion in economic aid to Western European countries in four years, had an economic aim: to build up markets for American exports. George Marshall [a general, then Secretary of State] was quoted in an early 1948 State Department bulletin:

The Marshall Plan of 1948, which gave $16 billion in economic aid to Western European countries in four years, had an economic aim: to build up markets for American exports. George Marshall [a general, then Secretary of State] was quoted in an early 1948 State Department bulletin:

“It is idle to think that a Europe left to its own efforts . .. would remain open to American business in the same way that we have known it in the past.”

The Marshall Plan also had a political motive. The Communist parties of Italy and France were strong, and the US used aid to keep Communists out of the cabinets of those countries. When the Plan was beginning, Truman’s Secretary of State Dean Acheson said:

“These measures of relief and reconstruction have been only in part suggested by humanitarianism. Your Congress has authorized and your Government is carrying out, a policy of relief and reconstruction today chiefly as a matter of national self-interest.”

From 1952 on, foreign aid was more and more obviously designed to build up military power in non-Communist countries. In the next ten years, of the $50 billion in aid granted by the US to ninety countries, only $5 billion was for non-military economic development.

From military aid, it was a short step to military intervention. In Iran, in 1953, the CIA succeeded in overthrowing a government which nationalized ARAMCO. In Guatemala, in 1954, a legally elected government was overthrown by an invasion force of mercenaries trained by the CIA at military bases in Honduras and Nicaragua and supported by American fighter planes flown by American pilots. The invasion put into power Colonel Carlos Armas, who had at one time received military training at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The government that the U.S. overthrew was the most democratic Guatemala had ever had. What was most unsettling to American business interests was that the government had expropriated 234,000 acres of land owned by United Fruit, offering compensation that United Fruit called ‘unacceptable.’ Armas, in power, gave the land back to the company, abolished the tax on interest and dividends to foreign investors, eliminated the secret ballot, and jailed thousands of political critics.

The success of the coalition in creating a national anti-Communist consensus was shown by how certain important news publications cooperated with the Kennedy administration in deceiving the American public on the Cuban invasion. The New Republic was about to print an article on the CIA training of Cuban exiles, a few weeks before the invasion. Historian Arthur Schlesinger was given copies of the article in advance. He showed them to Kennedy, who asked that the article not be printed, and The New Republic self censored. By 1960, the fifteen-year effort since the end of World War II to break up the radical upsurge of the New Deal and wartime years seemed successful. The Communist party was in disarray, its leaders in jail, its membership shrunken, its influence in the trade union movement very small; the military budget was taking half of the national budget, but the public was happy.

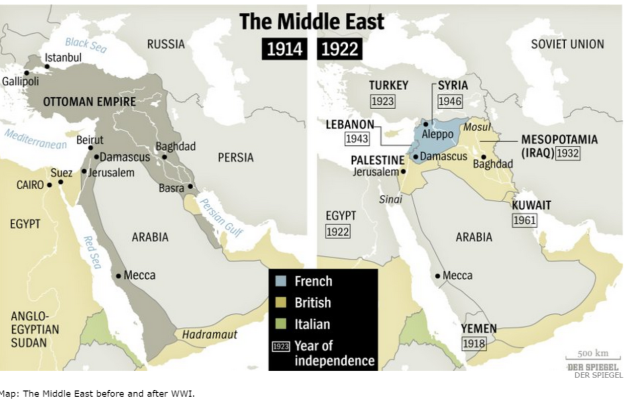

George Kennan, head of the State Department policy planning staff, wrote a paper in 1948 in which he noted that the United States has half the world’s wealth but only 6% of its population, and our primary goal in foreign policy must be, as he put it, to “maintain this disparity.” He was referring specifically to Asia, but the principle was general. And in order to do so, we must put aside all “vague and idealistic slogans” about democracy and human rights. Then, in the same paper, he and his staff went through the world and assigned to each part of the world in which the US would have unchallenged power. The Middle East obviously would provide the energy resources , pushing out Britain slowly over the years. Latin America we simply control. Southeast Asia provided resources and raw materials to the former colonial powers. Hence the support for French colonialism in recapturing its Indochinese colony.

The Cold War was a kind of a tacit compact between the United States and Russia; the US would be free to carry out violence, terror and atrocities with few limits in its own domains, and the Russians would be able to run their own dungeon without too much interference. So the Cold War in effect was a war of the US against the Third World, and of Russia against its domains in Eastern Europe. Each great power used the other’s threats as a pretext for repression and violence and destruction, the US against independent nationalism in the Third World, what was called ‘radical nationalism.’

“Radical means doesn’t follow orders. So, there’s this constant struggle against even a tiny place e.g. Grenada. If it has successful independent development, others might get the idea that they can follow, the rot will spread so you’ve got to stamp it out right at the source. It’s not a novel idea. Any mafia don will explain it to you.”

So, November 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, the Soviet Union soon collapsed. So what did the US do? The pretext for everything that had happened in the past was the monolithic and ruthless conspiracy’ attempting to take over the world, as John F Kennedy called it. Well, now the monolithic and ruthless conspiracy was gone, we do is exactly the same thing but with different pretexts.

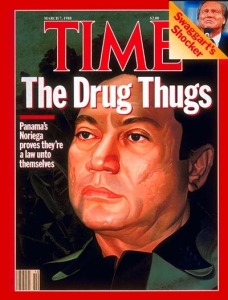

A couple of weeks after the Berlin Wall fell, the US invaded Panama, killing unknown numbers of people. The point of the invasion was to kidnap a a minor thug, who was brought to the United States, tried, sentenced for crimes that he had committed when he was on the CIA payroll. But for that we had to invade Panama and install a government of bankers and narco-traffickers. In early 1990, George Bush gave his new budget request. Turns out, it’s exactly the same as before. We still have to have a massive military force, and we have to maintain what they called the Defense Industrial Base.

A couple of weeks after the Berlin Wall fell, the US invaded Panama, killing unknown numbers of people. The point of the invasion was to kidnap a a minor thug, who was brought to the United States, tried, sentenced for crimes that he had committed when he was on the CIA payroll. But for that we had to invade Panama and install a government of bankers and narco-traffickers. In early 1990, George Bush gave his new budget request. Turns out, it’s exactly the same as before. We still have to have a massive military force, and we have to maintain what they called the Defense Industrial Base.

For centuries, governments owned and operated their own arms manufacturing companies, usually state monopolies. By the late 19th century the new complexity of modern warfare required industry to be devoted to the research and development of rapidly maturing technologies. Rifled, automatic firearms, artillery and gunboats, and later, mechanized armor, aircraft and missiles required specialized knowledge and technology to build. For this reason, governments increasingly began to integrate private firms into the war effort by contracting out weapons production to them. It was this relationship that marked the creation of the military–industrial complex [MIC].

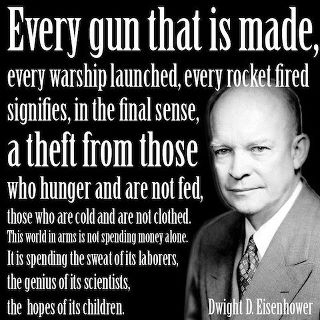

The MIC comprises the policy and financial relationships which exist between legislators, armed forces, and the arms industry that supports them. These relationships include political contributions, approval for military spending, lobbying to support bureaucracies, and oversight of the industry. The term is used to include the entire network of contracts and flows of money and resources among individuals as well as corporations and institutions of the defense contractors, The Pentagon, the Congress and executive branch. In his farewell speech, Eisenhower raised the issue of the Cold War and continued with a warning that:

“we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military–industrial complex.” He elaborated, “we recognize … the potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist … Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together.”

George Kennan wrote in his preface to The Pathology of Power;

“Were the Soviet Union to sink tomorrow under the waters of the ocean, the American military–industrial complex would have to remain, substantially unchanged, until some other adversary could be invented. Anything else would be an unacceptable shock to the American economy.”

The constant threat of conflict created an atmosphere that underpinned the need for sustained military procurement. In 1977, following the Vietnam war, Carter began his presidency with “a determination to break from America’s militarized past.” However, increased defense spending during and after his administration brought the MIC back into prominence.

According to SIPRI total world spending on military expenses in 2009 was $1.5 trillion. 46% of this total, roughly $712 billion was spent by the US. The military budget of the US for 2009 was $515 billion. Overall the United States government is spending about $1 trillion annually on defense related purposes. The industry tends to contribute heavily to incumbent members of Congress. In a 2012 story, Salon reported;

“Despite a decline in global arms sales in 2010 due to recessionary pressures, the U.S. increased its market share, accounting for 53% of the trade, on pace to deliver more than $46 billion in foreign arms sales.”

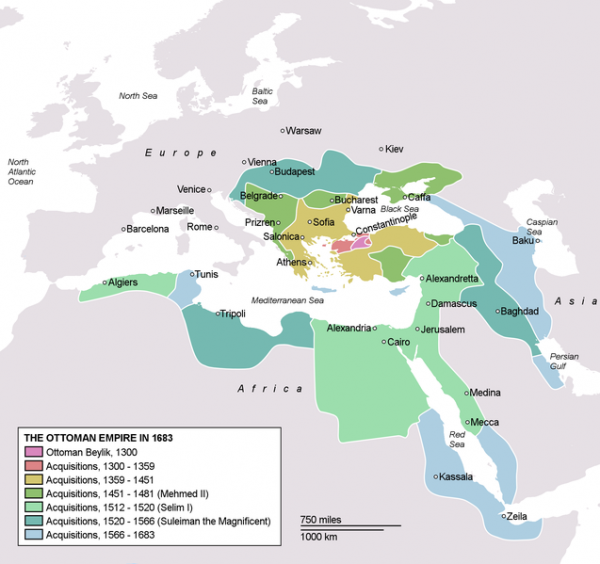

True power in the realm devolved to others, such as well-placed harem women and various segments of the military establishment. Among the soldier classes rising in importance were the elite Janissary guards. The Janissaries, in particular,were a volatile and unpredictable group. When the empire began running out of Moslem warriors, it formed the Janissaries, drawn in large measure from Christian boys “levied” from their eastern European villages. In an Ottoman protocol called the Collection, children were selected pro rata, systematically taken from their families, and raised as a special standing army. The abducted ones were nicknamed New Troops, Yen Ceri in Turkish, transliterated Janissary. From time to time, they would stage their own revolts.

True power in the realm devolved to others, such as well-placed harem women and various segments of the military establishment. Among the soldier classes rising in importance were the elite Janissary guards. The Janissaries, in particular,were a volatile and unpredictable group. When the empire began running out of Moslem warriors, it formed the Janissaries, drawn in large measure from Christian boys “levied” from their eastern European villages. In an Ottoman protocol called the Collection, children were selected pro rata, systematically taken from their families, and raised as a special standing army. The abducted ones were nicknamed New Troops, Yen Ceri in Turkish, transliterated Janissary. From time to time, they would stage their own revolts.

mosques, and Christian churches in the Mongol capital

mosques, and Christian churches in the Mongol capital

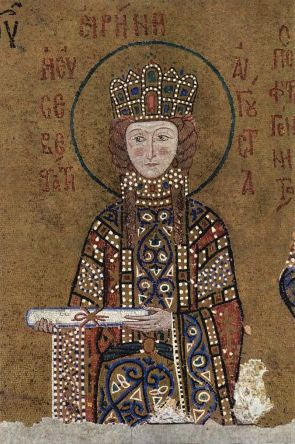

uncle was possibly general of Hellas at the end of the 8th century. She was brought to Constantinople by Emperor Constantine V and was married to his son

uncle was possibly general of Hellas at the end of the 8th century. She was brought to Constantinople by Emperor Constantine V and was married to his son

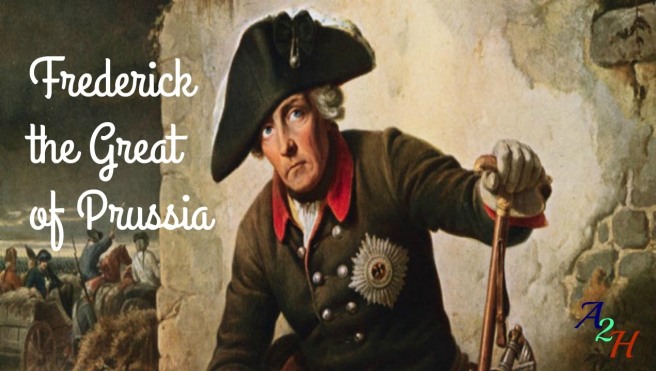

As Prussia became increasingly tied economically and politically with Poland, and the wars became more and more devastating to the borderlands, and as the policies and attitude of the King of Poland were more liberal towards the Prussian burghers and nobility than that of the Order, the rift between the Teutonic Knights and their subjects widened. At first, the estates opposed the Order passively, by denying requests for additional taxes and support in Order wars with Poland; by the 1440’s Prussian estates acted openly in defiance of the Teutonic Order, rebelling against the knights and siding with Poland militarily.

As Prussia became increasingly tied economically and politically with Poland, and the wars became more and more devastating to the borderlands, and as the policies and attitude of the King of Poland were more liberal towards the Prussian burghers and nobility than that of the Order, the rift between the Teutonic Knights and their subjects widened. At first, the estates opposed the Order passively, by denying requests for additional taxes and support in Order wars with Poland; by the 1440’s Prussian estates acted openly in defiance of the Teutonic Order, rebelling against the knights and siding with Poland militarily. Hohenzollern family, held as a fief of the Polish crown. In 1618 the Hohenzollern line died out and the duchy passed to a Hohenzollern cousin, the elector of Brandenburg. On the coast between Brandenburg and the elector’s new possession of ducal Prussia there lay another part of Prussia known as royal Prussia, it included the valuable harbor of Gdansk. Royal Prussia is fully integrated into the Polish kingdom. Ducal Prussia, by contrast, is largely German as a result of German settlers being brought there in the 13th century to till the soil and to control the pagan Prussians. This ethnic division, with a Polish region between two German ones, is one of the more disastrous accidents of history.

Hohenzollern family, held as a fief of the Polish crown. In 1618 the Hohenzollern line died out and the duchy passed to a Hohenzollern cousin, the elector of Brandenburg. On the coast between Brandenburg and the elector’s new possession of ducal Prussia there lay another part of Prussia known as royal Prussia, it included the valuable harbor of Gdansk. Royal Prussia is fully integrated into the Polish kingdom. Ducal Prussia, by contrast, is largely German as a result of German settlers being brought there in the 13th century to till the soil and to control the pagan Prussians. This ethnic division, with a Polish region between two German ones, is one of the more disastrous accidents of history. The isolation of the Germans in ducal Prussia was irrelevant while Europe still had a patchwork of allegiances, but by the 17th century there was a trend towards independent states. Inevitably political pressure built up between Brandenburg and ducal Prussia particularly after Brandenburg acquired another long stretch of Baltic coast [eastern Pomerania] in 1648. The elector Frederick William of Brandenburg succeeded, through a well judged blend of warfare and diplomacy, in severing the feudal link between his duchy and the Polish kingdom. Poland was forced to concede its loss of ducal Prussia in 1657 and the international community recognized Prussia as an independent duchy. This achievement enabled Frederick William’s son, Frederick III to achieve the crucial next step.

The isolation of the Germans in ducal Prussia was irrelevant while Europe still had a patchwork of allegiances, but by the 17th century there was a trend towards independent states. Inevitably political pressure built up between Brandenburg and ducal Prussia particularly after Brandenburg acquired another long stretch of Baltic coast [eastern Pomerania] in 1648. The elector Frederick William of Brandenburg succeeded, through a well judged blend of warfare and diplomacy, in severing the feudal link between his duchy and the Polish kingdom. Poland was forced to concede its loss of ducal Prussia in 1657 and the international community recognized Prussia as an independent duchy. This achievement enabled Frederick William’s son, Frederick III to achieve the crucial next step.