Wounded Healer: Rollo May's Psycho-Spiritual Odyssey

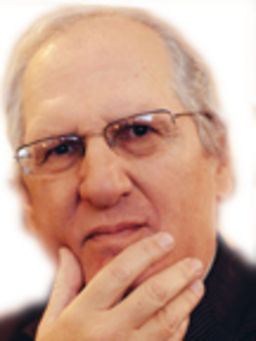

Part 1: A book review and conversation with biographer Robert Abzug.

Posted Jan 08, 2021

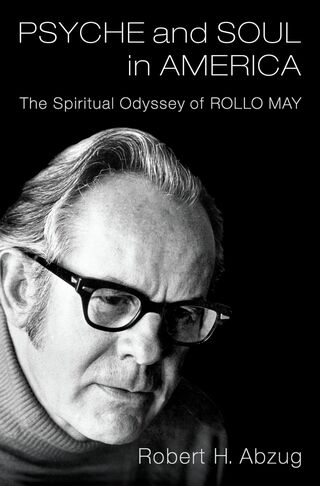

Historian Robert Abzug's brand new biography of famed existential psychologist Dr. Rollo May, Psyche and Soul in America: The Spiritual Odyssey of Rollo May, will be released on February 1, 2021, by Oxford University Press. The book is remarkable not only because it is the first major authorized biography written about May (1909-1994), has been several decades in the making, and is extremely well-informed and finely written, but also because of its unblinking revelations regarding Rollo's dark, deeply troubled personal life obscured till now for most of us by his impressive professional and public persona.

Throughout this thoroughly riveting book, Abzug carefully and empathically illuminates, scrutinizes, and exposes in intimate detail what Jung might have called May's "shadow." (See my prior post.) However, it is crucial to point out that May himself, several decades ago, while still very much alive, willingly and deliberately provided unimpeded access to these very private particulars regarding his personal and professional history, courageously demonstrating an extraordinary openness about, and admirable acceptance of, his own humanity, complexes, and imperfections. Indeed, as a former pupil and protégé of Rollo May (see my prior post), I personally learned a great deal about him that I never knew—not all of which is flattering, complimentary, or positive.

In this sense, the biography serves, on one hand, to radically deflate the one dimensional, idealized transference some of us projected upon Rollo--that of the wise, suave, erudite, enlightened, articulate, mellifluous-voiced, self-assured, charming, gifted, generous, caring, empathic, charismatic, accomplished, distinguished, consummate psychotherapist, teacher, lecturer, author, and brilliant public intellectual—while at the same time truly humanizing May by disclosing how he, like all of us to some extent, struggled mightily with his own tormenting emotional demons: painful and distressing feelings of loneliness, inferiority, anxiety, depression, jealousy, insecurity, unlovability, fear of intimacy, and dread of abandonment. These seemingly disparate traits or characteristics within the same person are always present in some measure, inextricably integral and intertwined parts of the human personality. Together, they constitute the whole person.

Sigmund Freud famously observed that we are all neurotic, suffered himself from clinically significant anxiety symptoms, and partly from his own neurotic conflicts and obsessions came psychoanalysis. C. G. Jung, who experienced during midlife a protracted and debilitating breakdown or "confrontation with the unconscious" which psychiatric historian Henri Ellenberger in hindsight called a "creative illness," noted that we all carry a compensatory shadow concealed behind our persona, and once quipped that, of course, we all have complexes--but the crucial question is whether we have complexes or they have us. (See my prior post.) Indeed, Abzug's sympathetic biography depicts May, the much-celebrated author of books such as The Meaning of Anxiety, Man's Search for Himself, Psychology and the Human Dilemma, Love and Will, Power and Innocence, Freedom and Destiny, The Courage to Create, The Discovery of Being, and The Cry for Myth, to have been a truly daimonic man--much like Freud and Jung, and other renowned "wounded healers" (see my prior post)--unrelentingly driven by his personal demons and "deep craving, a keen urge" and commitment to consciously come to terms with and eventually creatively employ what he learned from them to help himself, fellow human beings, and the world.

To paraphrase something May once said privately to me when referring, if I recall correctly, to our all-too-human frailties and faults, "The only difference between me and others is that I admit these feelings." As we know from the therapeutic process of "making the unconscious conscious," self-awareness is essential to such profound self-acceptance. Indeed, if truth be told, such acceptance--starting with what May's friend and colleague Carl Rogers called "unconditional acceptance" of the client by the therapist--is for me one of the essential secrets of real psychotherapy (see my prior post). Self-acceptance, certainly, but more specifically, acceptance of the "shadow" or what May called the daimonic in both ourselves, others, and nature, including our inherent human capacity for cruelty, hostility, evil and destructiveness; and acceptance of the daunting and tragic existential facts of life, like death, aloneness, loss, suffering, and absurdity; of existential reality exactly as it is; and of fate, i.e., those "givens" in life that we do not choose and cannot control. How we deal with our fate--for example, as in May's case, having been born into a fairly dysfunctional Mid-western family with an unstable borderline mother and very religious but irresponsible philandering father--ultimately determines our destiny. Paradoxically, we can either accept or rebelliously fight against fate or destiny; but even to effectively fight against it, we must first accept (rather than deny) it's reality. Ultimately, May appears to have embraced his difficult fate—including family dynamics and a near-fatal two-year bout with tuberculosis during midlife—as the driving force behind his creative destiny. This attitude of not only accepting but embracing one's fate, amor fati, as Friedrich Nietzsche phrased it, is a spiritual achievement of the highest order.

Our earliest fate influences, as May observed, the formation of one's personal myth: the inner narrative of how we make sense of and see ourselves, the world around us, and our place in it. Rollo's myth was, seemingly from the very beginning, that of the helper, the healer, the caretaker, the peacemaker, which was his self-perceived role in the family system. May's destiny was first to seek salvation, self-esteem, and sense of purpose and meaning in life first through conventional organized religion, believing this to be his messianic calling, attending theological seminary and briefly becoming a Congregational minister; and later, in midlife, taking a different but, for Rollo, closely related tack: choosing to study counseling and psychology, eventually becoming a clinical psychologist, psychoanalyst, preeminent exponent of existential therapy (see my prior post), prolific bestselling author, popular lecturer, philosopher, and psycho-spiritual minister to the rampant collective angst, confusion, alienation, anomie, loss of meaning, and disorientation of his day.

Over the lengthy course of Rollo's illustrious and epic career as a therapist, he not only provided psychological treatment to suffering multitudes, but, as is true of most fully committed clinicians, participated at different times in personal psychotherapy for his own problems with various practitioners, including--subsequent to his self-described brief "nervous breakdown" during his early 20s while living and teaching abroad—an Adlerian in Vienna, Rankian disciple Harry Bone, neo-Freudian analyst Erich Fromm and his wife Frieda Fromm-Reichman, psychoanalysts Alberta Szalita and Clara Thompson, and, much later, while in his 70s, senior Jungian analyst Joseph Henderson in San Francisco.

Nonetheless, as the persistently stormy course of May's "messy" psycho-spiritual odyssey--reminiscent of the tumultuous mythic voyage of the Greek hero Odysseus himself--demonstrates, psychotherapy does not nor cannot completely exorcise, eliminate or eradicate one's demons. Nor should it realistically try to. For, as I have elsewhere written (1996, p. 286}, "They have taken up permanent residence; turned into an integral part of us; molded our personality; made us who we are." But therapy can, as Rollo rightly contended, help us learn to accept and live more freely, responsibly, lovingly, compassionately, and creatively with them in a hard-won state of conscious awareness the Greek philosopher Aristotle termed eudaimonia. And to become more acutely sensitive, attuned or receptive to our own being and appreciative of archetypal and ultimate existential concerns like love, will, soul, spirit, purpose, freedom, destiny, responsibility, "beauty, God, [and] death" in the process. (See my prior post.)

Psychotherapy cannot cure life's insoluble or irresolvable problems, and clearly cannot undo or change the past. But it can help place such significant matters in a new and different perspective, a process C.G. Jung likened to the difference between being caught in the midst of a violent thunderstorm and becoming able to eventually view that storm from a more objective, comprehensive, loftier, insightful or detached stance: the daimonic maelstrom remains but we have changed, outgrown, accepted, or transcended it. This psycho-spiritual expansion of consciousness can also profoundly influence how we experience and perceive—and what we decide to do or don't do in--the present and future. It can liberate and encourage us to bravely become more authentically and assertively ourselves in the world. To find and fulfill our destiny.

As psychotherapists, "our task," wrote May in 1991, near the end of his life, "is not to 'cure' people... Our task is to be guide, friend, and interpreter to persons on their journeys through their private hells and purgatories" (p. 165). Sadly, this psycho-spiritual understanding of the real meaning, purpose, and value of psychotherapy is antithetical to most mainstream treatment approaches practiced today. (See my prior post.)

Nevertheless, this mature recognition of both the intrinsic limits and transformative power of psychotherapy (see my prior post) is, to me, perhaps May's—and this moving biography's—most powerful, enduring, and important contribution. Robert Abzug's highly readable, literate, insightful, sophisticated, and gripping portrait of one of clinical psychology's most intrepid and influential pioneers, activists, visionaries, champions, and legendary practitioners serves to remind us that despite our complexes, cravings for control, power, and recognition, and daimonic capacity for anger, rage, hatred, and destructiveness, we human beings are equally capable of creativity, kindness, caring, love, compassion, and of constructively contributing to society and benefitting our fellow beings. Both possibilities are present. The existential choice and responsibility regarding how we will express ourselves in the world remain ours. Or, as May himself put it, "constructiveness and destructiveness have the same source in human personality. The source is simply human potential" (in Diamond, 1996, pp. xxi). And, what ultimately determines our destiny is how we consciously choose to manage, direct, channel, and express these vital human passions and potentialities, i.e., primarily for evil or good, destructiveness or creativity. The key is learning to courageously confront, accept, and creatively cohabitate with rather than habitually repress, reject, run from, deny or suppress our psychological devils and demons.

What soon follows next in Part 2 is the start of my extended conversation with May's authorized biographer Professor Robert Abzug, whom I have had the pleasure to know for a number of years now, about his important and long-awaited new book. Enjoy! And Happy New Year!!

References

Abzug, R. (2021). Psyche and soul in America: The spiritual odyssey of Rollo May. New York: Oxford University Press.

Diamond, S. (1996). Anger, madness, and the daimonic: The psychological genesis of violence, evil, and creativity. Foreword by Rollo May. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press.

May, R. (1969). Love and will. New York: W.W. Norton.

May, R. (1985). My quest for beauty. Dallas, Tx: Saybrook Publishing.

May, R. (1991). The cry for myth. New York: W.W. Norton.