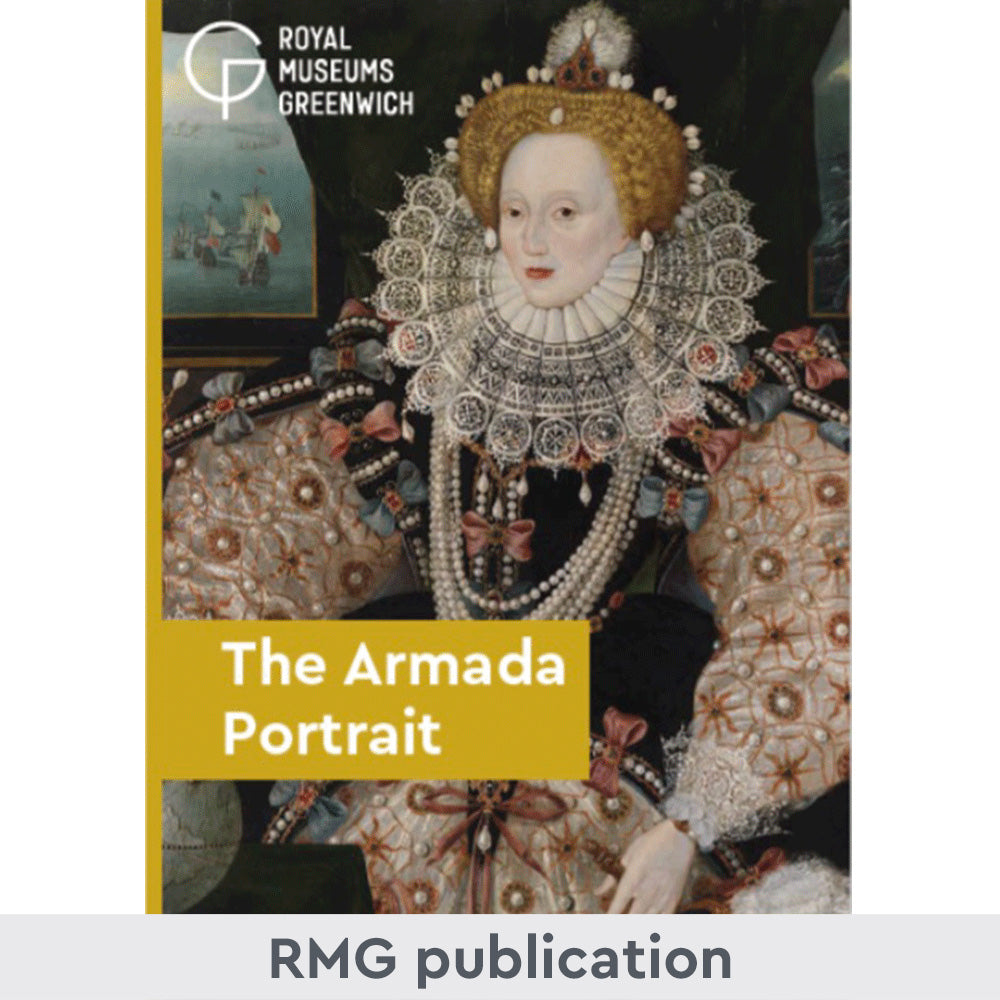

Elizabeth I and the Earl of Essex

Queen Elizabeth I's tempestuous relationship with Robert Devereux, the 2nd Earl of Essex, greatly influenced the latter part of her reign, and resulted in Essex's execution in 1601.

After the Armada, the war with Spain continued, problems in Ireland escalated and the death of Elizabeth's closest friends and advisers, including Dudley (1588), Walsingham (1590), Hatton (1591) and Cecil (1598), left the ageing Queen increasingly isolated.

The rise and fall of Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex

A number of the old guard were replaced by younger relatives, notably Dudley's stepson Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, and Robert Cecil, William Cecil's son.

Although Robert Dudley and William Cecil were often at loggerheads over military and religious policy, it was nothing compared to the rivalry and animosity that developed between their sons. The most serious division between the two camps was over foreign policy. Essex's competition for influence with the Queen, combined with his insatiable ambition, lead to a fall from grace that was as dramatic and rapid as his rise to favour.

The Earl of Essex in Ireland

With the death of Dudley, Elizabeth transferred some of her affection to his stepson, and Essex continued the courtier's role of currying favour with the Queen through flattery and flirtation, despite being 34 years her junior. Elizabeth indulged him and put him in charge of a number of important military operations. Essex was tall, handsome and hungry for martial success. He was also arrogant, ambitious and temperamental.

In April 1599 Essex was sent to Ireland as Lieutenant and Governor General, with an army of 17,000 men and explicit instructions to crush the Earl of Tyrone's rebellion and bring Ireland under control. Instead of following orders, Essex had a secret meeting with Tyrone, made a truce in Elizabeth's name and abandoned his post to return to London and explain his decision to the Queen.

Elizabeth was furious and had him put under house arrest while an inquiry into his behaviour was held. He was found guilty of disobedience and dereliction of duty, stripped of most of his positions, and banished from court as punishment. In August 1600 Essex was released and determined to regain his position as favourite and councillor. He wrote Elizabeth many pleading and outraged letters.

A bid for power: the Earl of Essex's rebellion

In September 1600, the Queen refused to renew the lease and patent on Essex’s farm (provitable control) of wines. Essex was livid and decided to make a bid for power. He and his supporters, mostly disaffected nobles and soldiers, planned to capture the Queen, rid the Council of the 'caterpillars of the Commonwealth' and proclaim James VI her successor.

In 8 February 1601 they marched into the City where they thought they would be joined by legions of delighted Londoners. The anticipated support did not materialise and the rebellion collapsed within the day. Essex and some of his co-conspirators were executed for treason on 25 February 1601. Elizabeth was shocked and devastated by his betrayal.

The end of Queen Elizabeth’s reign

The question of succession had been an issue for Queen Elizabeth's government from the moment she came to the throne. Her advancing age heightened these concerns but Elizabeth continued to ban discussion on the matter. Many felt that Elizabeth's cousin and godson, James VI of Scotland and Protestant son of Queen Mary I, had the best claim to the throne. Elizabeth refused to discuss it.

Robert Cecil, the dominant politician of Elizabeth's final years, took it upon himself to arrange for a smooth succession. He felt that James was the best candidate and began secret correspondence with him in March 1601.

Elizabeth was at Richmond Palace when her health began to fail in February 1603. As her condition deteriorated, Cecil sent James a draft proclamation, which he approved.

When did Elizabeth I die?

Surrounded by her Privy Councillors and bishops, Elizabeth died at the age of 69 in the early hours of 24 March 1603. According to the royal chaplain, Dr Henry Parry, it was a 'good death', as

‘hir Majestie departed this lyfe, mildly like a lambe, easily like a ripe apple from the tree...’

James I and the Stuart dynasty

Cecil staged a magnificent funeral for the last and most celebrated Tudor monarch on 28 April 1603. Throngs lined the streets to say their farewells and mourn their dead queen.

A few days later, James VI of Scotland rode from Edinburgh to London to take the English throne unchallenged, uniting the two crowns and ushering in the Stuart dynasty.

Using our collections for research

The collections at Royal Museums Greenwich offer a world-class resource for researching maritime history, astronomy and time.

Find out how you can use our collections for research