If you listen to the podcast Dolly Parton’s America, you may have noticed a weird little etymological moment in the latest episode, “Dolly Parton’s America.” In the course of the episode, the host, Jad Abumrad, visits a history class at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville called, well, Dolly Parton’s America. (Yes, Abumrad makes clear, they did receive permission from the professor, Lynn Sacco, to name their podcast after her class.) Where do you think the term redneck came from? If you’re like me, this episode made you question your priors.

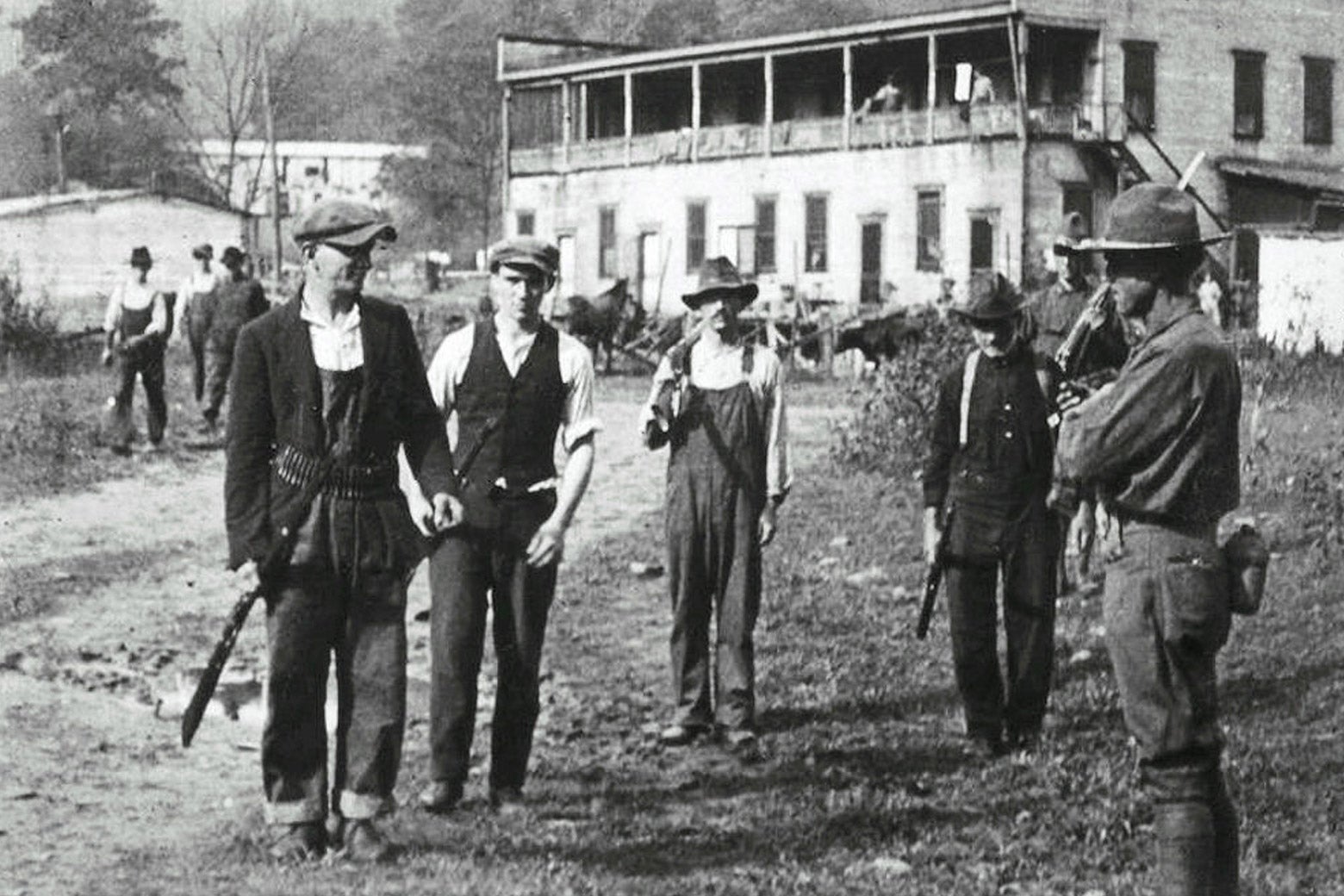

This episode is, in part, about external judgment of Appalachia and the South, and there is a discussion partway through with historian Elizabeth Catte, whose 2018 book, What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, is an instant classic on the topic. Starting around 27:30, Catte describes the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain, in West Virginia, in which 10,000 to 20,000 coal miners looking for the right to unionize clashed with company enforcers, and then with the National Guard, over a deadly week of fighting. “It was the largest uprising since the Civil War, and one of the most significant labor uprisings in American history,” Catte says.

Then, in the originally published version of the episode (WNYC has since added clarifying narration and posted an editor’s note on the show page in response to Slate’s inquiries), Abumrad seems to cut away from the interview, to a summarizing comment: “And the kicker is, the people marching that day wore red bandanas around their necks, which is why they were known as rednecks. That’s where the term came from.” In what seems to be a cutback to the interview, Catte says “Mm-hm, yes, yeah.” The producer, Shima Oliaee, exclaims, “I thought it was about sunburn!” And then Catte moves on to discuss the origins of the word hillbilly.

I, too, was confused to hear this new version of an old bit of folk wisdom, and went to check up on it. The Oxford English Dictionary finds derogatory usages for redneck—when defined as “a poorly educated white person working as an agricultural laborer or from a rural area in the southern United States, typically considered as holding bigoted or reactionary attitudes”—much earlier than 1921: 1891, 1904, 1913. What gives?

I emailed Catte to ask if she had heard the episode she appeared in and what she thought of the way the interview had been edited. She wrote that she hadn’t had a chance to listen. But, she wrote, “it was not my intention to claim the mine wars as the origin of the term, but instead to periodize its transformation from a more generic epithet to something specific to group identity and union membership, particularly among coal miners, which is built into the way that many folks in Appalachia today reclaim the term.”

Abumrad, for his part, replied to an email inquiry by acknowledging the error. “I might not have used the right words,” he wrote. “The etymology is older and more complex and disputed. My main point was simply that poor white southerners are often labeled with slurs that historically could be read to mean the opposite of what we think they mean.”

This history of disputation around the uses of the term is what’s most interesting here, and it’s also what resists a “just-so” story about the word’s origins. Catte pointed me to a 2006 article by historian Patrick Huber in the journal Western Folklore that she said formed the basis for her own interpretation. Huber’s argument—that redneck, in the 1910s through the 1930s, sometimes meant “Communist,” or at least “a miner who was a member of a labor union,” especially one on strike—made it clear that this usage was a strategic reclamation of a word that had been used as a slur. Some union organizers, Huber found, used red bandanas and the term redneck as a way to culturally integrate groups of white, black, and immigrant miners—who were often set against each other by owners eager to divide labor’s power—into a single identity. Because miners often wore red handkerchiefs to protect their faces and necks from coal dust, the bandana was a symbol of labor that was universal among ethnicities and races.

Here is part of a union song collected by industrial folklorist George Korson, which dates to 1927:

Red Necks, keep them scabs away,

Red Necks, fight them every day.

Now any old time you see a scab passin’ by,

Now don’t hesitate—blacken both of his eyes.

At the same time, in a derivation that Huber calls “ambiguous,” coal operators occasionally used redneck when meaning to invoke the term red to denigrate union members. In this bizarre turn of the screw, redneck, in some specific times and probably only a few places, actually functioned as an anti-Communist slur.

This podcast episode isn’t the first time the “red bandana” etymology of rednecks has popped up in media over the past couple of years, as the coasts and big cities have become very interested (again!) in what’s going on in Appalachia. In Fahrenheit 11/9, Michael Moore, in conversation with then–congressional candidate Richard Ojeda, notes that some strikers involved in the 2018 West Virginia teachers’ strike wore red bandanas, as well. “The bandanas have a special meaning, going back to the 1920s, when tens of thousands of coal miners went on strike, wearing red bandanas around their necks to identify themselves as pro-union, and thus popularizing the term redneck,” Moore says.

That “popularizing” does important work, but it seems Moore might have elided it in later public appearances. At a 2018 screening of the documentary at the Toronto International Film Festival, according to the Austin-American Statesman’s Charles Ealy, audience members received red bandanas upon entering the theater; Moore then asked them to tie them around their necks. “He said,” a skeptical Ealy reported, “that the term redneck derived from members of labor unions in the coal industry who wore red bandanas to signify their loyalty.”

Is it picking nits, to call left-leaning media on this mistake? The “other” origin story makes for such a fun factoid, and clearly it’s more encouraging to audiences who may be worried about Trump supporters to hear that redneck has its definite origin in union activity. But it is, as always, more complicated than that. The part of the story that describes people’s purposeful reclamation of a negative term, in service of unity and empowerment, should also be told.