Rebel in the Rye Is Phony Through and Through

Danny Strong’s directorial debut stars Nicholas Hoult as J.D. Salinger, in a film that misses the mark in trying to capture his unique talent.

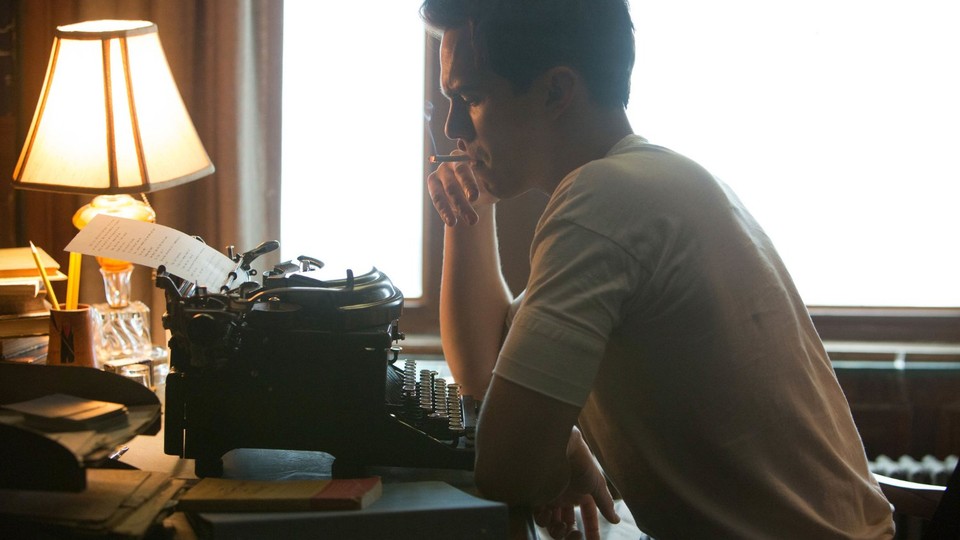

Jerry (Nicholas Hoult), the outspoken new student in Whit Burnett’s (Kevin Spacey) creative writing class at Columbia, isn’t your average writer. He speaks out of turn, offers haughty responses to constructive criticism, and refuses to kowtow to even the simplest notes on his work, lest it constrain his creativity. You see, Jerry is a young man blessed with extraordinary talent that will later catapult him to success. How do we know? Because his real name is J.D. Salinger, and the subject of the short story he’s writing is named Holden Caulfield.

The new film about Salinger’s career, Rebel in the Rye, is a work of searing mediocrity about an author who was horrified by the very idea of mediocrity, eventually sealing himself away from public life rather than subject his work to mainstream scrutiny. Written and directed by Danny Strong, the Hollywood scripter behind true-story movies like The Butler, Recount, and Game Change, Rebel in the Rye is immediately and passionately convinced of its hero’s genius before he’s written a line or uttered a word of dialogue. Strong seems to believe Salinger’s name, and his salty attitude, are enough to convince the audience of his talent. Why else would the director not devote a single moment in the film’s 105-minute running time to trying to understand what distinguished the young author from his contemporaries?

Rebel in the Rye offers a cursory glance at every stage of Salinger’s career, including his time at Columbia, his service in World War II, his emergence as a short-story writer for The New Yorker, the 1951 publication of The Catcher in the Rye and its overwhelming success, and his later retreat into total seclusion in New Hampshire. Based on J.D. Salinger: A Life by Kenneth Slawenski, the movie sticks to the formula of Strong’s other scripts, focusing on major moments in the life of a public figure rather than concentrating on any one period in history. In Rebel in the Rye, Strong leaves the work of establishing Salinger’s genius to the ensemble around him, who consistently and loudly praise how exceptional his work is.

Dramatizing the creative process, particularly that of a writer, is never easy to do on film. Strong’s concept, as much as I could understand it, is that Salinger’s youthful attitude ended up mirroring the startling rebelliousness of his most famous character, Holden Caulfield. That’s as close as Strong gets to showing how Salinger drew inspiration from the world around him, though there’s very little mention of any of his other works, particularly his short stories about the Glass family, beyond their titles.

But Salinger is hardly the most dynamic protagonist, and he’s certainly not interesting enough to come across as a generational talent. Strong takes the audience through some early aspects of the writer’s biography, like his romance with Eugene O’Neill’s daughter Oona (Zoey Deutch) and his early rejections from The New Yorker, but Hoult plays Salinger as a typically frustrated young man, trying to make a creative breakthrough and angry at how closed-off New York’s literary establishment seems. The film conveys his struggles in the most shallow ways possible. Writer’s block sees Salinger bitterly tossing his pencil across the room, while his announcement that he’s pursuing a career in writing is greeted with warnings from his father Sol (Victor Garber) that he’ll never amount to anything. When Salinger does make it, the film barely shifts in tone.

Where did Holden Caulfield come from? According to Strong, he was the personification of Salinger’s fight against literary heterodoxy, with the book’s grim outlook forged in the fires of World War II. The film lacks the budget to stage much of Salinger’s service in Europe, instead subjecting us to rote flashbacks of battlefield chaos and a scene where he rails at Burnett about the friends he lost overseas. The genesis of The Catcher in the Rye appears to be little more than Burnett encouraging Salinger to turn his Caulfield short story into a novel; once that decision is made, the rest is a dramatically inert inevitability.

Of course, Salinger encounters resistance from the stuffy publishing world—editor’s notes, suggestions of plot changes, horror at the novel’s frank language and then-unusual portrait of teenage disaffection. But the author stands his ground, telling his agent (Sarah Paulson, one of the movie’s many wasted talents), “I won’t do it, I won’t change a word! Holden would not approve!” Holden would certainly not approve of this film, one that crams an author’s mysterious and fascinating legacy into the most basic of biopic formulas. I can’t imagine many viewers will, either.