by Heather R. Darsie

On 15 October 1582, the Gregorian calendar was decreed via papal bull. Pope Gregory XIII, under the bull Inter gravissimas or Of Great Importance, corrected calculation of a year from 365.25 days in the Julian calendar to 365.2422 days in Gregorian. Also, the Julian calendar had 100 leap days over 400 years, whereas the proposed Gregorian would have only 97. Most centennial years would not have a leap year, unless the number could be divided evenly by four hundred. For example, the year 2000 could be divided evenly by 400, so it was a leap year. The last time a leap year occurred during a centennial year was 1600, when Elizabeth I was still Queen of England.

The Julian calendar had been in use since around 45 BC, replacing the much older Roman calendar. Unfortunately, given the state of the Reformation across much of Europe, the calendar was adopted slowly. The bull went into effect in the Papal Estates immediately, because that was the only area over which the Pope had control. People in the Papal Estates went to sleep on 4 October 1582 awakened on 15 October 1582. The new calendar changed the timing of Easter celebrations as well.

Pope Gregory XIII by Lavinia Fontana, c. 16th century, via Wikimedia Commons

Correction of the calendar was certainly decades, if not centuries, in the making. The date for Easter began to drift farther and farther away from what was recognized as the correct canonical date by the Catholic church. As early as the 8th century, the timing drift was noticeable.

No real collective effort was dedicated to correcting the calendar until 1545. Pope Paul III was given permission at the Council of Trent to correct the error. Pope Paul’s main duty was to correct the date of the vernal, or spring, equinox to what was established in 325 by the Council of Nicaea.

In the 1570s, it was sorted that the Julian calendar caused a drift of roughly three days every four hundred years. The first proposal for correcting the drifting dates was to omit ten leap days over forty years, thereby slowly correcting the Julian calendar.

Calendar printed by Aloysius Lilius from 1582 showing October, November, and December, via Wikimedia Commons.

France, Portugal, and Spain, still loyal to the Pope despite any internal struggles, adopted the new Gregorian calendar right away. Italy, of course, did as well. Portions of the Holy Roman Empire, a large part of which is now Germany, adopted the new calendar in 1582 as well. Most of the Protestant areas within the Holy Roman Empire did not, which certainly made for interesting record-keeping discrepancies!

Elizabeth I, initially in favor of a new calendar, quietly let the idea slip by. A royal commission had recommended to Elizabeth that ten days be dropped from the calendar. It likely seemed too close to the new Catholic-endorsed calendar. The Gregorian calendar was not adopted in England/Great Britain until 1752. September of 1752 was shortened by eleven days, with people going to bed on 2 September only to wake up on 14 September.

The adoption of the Gregorian calendar in Catholic territories is the reason why sometimes one sees “old” and “new” dates for events happening in the Elizabethan period and beyond.

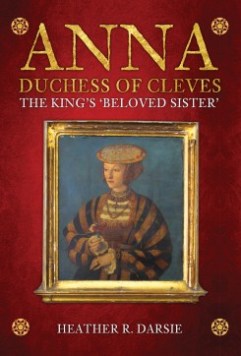

Love learning about the Early Modern period? Are you interested in Tudor history or Women’s history? Then check out my book, Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s ‘Beloved Sister’, a new biography about Anna of Cleves told from the German perspective!

You Might Also Like

Here it was only adopted in the eighteenth century. The loss of eleven days pay set off protests.

LikeLike