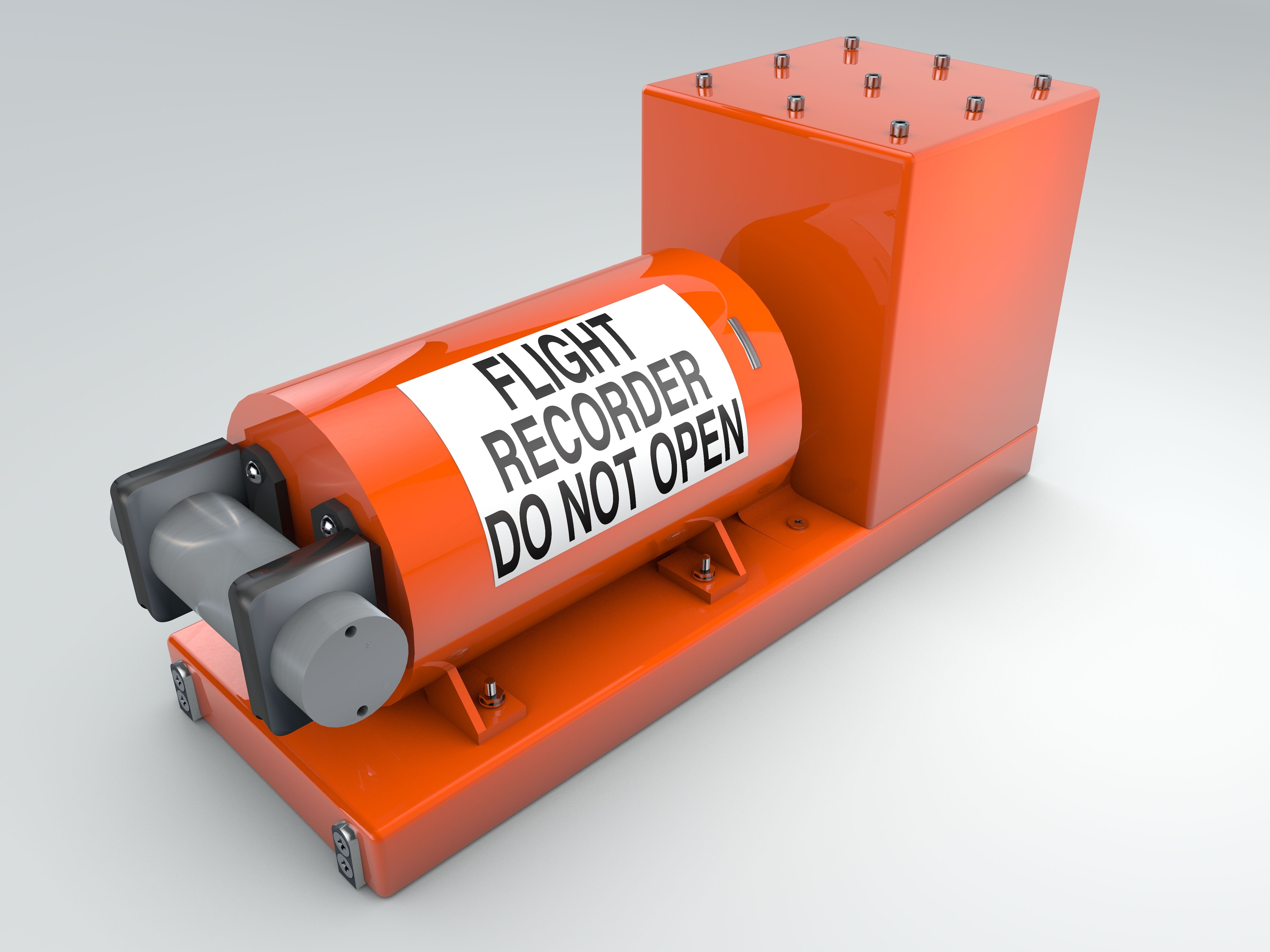

Aircraft flight data recorders are used by investigators to help determine the cause of air crashes. These so-called black boxes record flight data and cockpit voices and are retrieved after accidents, with the data hopefully helping establish what happened to the aircraft. To be useful, they need to survive – and they are built to do this in several ways.

The black box

“Black box” recording and storage equipment are compulsory on all commercial and corporate flights. The black box is actually two separate pieces of equipment - a cockpit voice recorder (CVR) and a flight data recorder (FDR). These record and store all audio, flight control info, and other data throughout the flight. The flight data recorder will record data for at least the flight duration (25 hours under European regulations), whereas the voice recorder should record for at least the last two hours.

The term “black box” was first used by the British during World War Two and referred to the secret development of radar and electronic navigational aids in British aircraft. Commercial use began later, with various designs being developed, and use in commercial aircraft was mandated from the late 1960s.

Love aviation history? Discover more of our stories here

Designed to survive

The critical part of the black box is the crash-survivable memory and data storage. Earlier recorders used analog tape, but digital solid-state memory is used today. This is contained in a cylindrical housing engineered to survive extreme impact, heat, and pressure and protect the memory inside. Design and survival methods, guidance, and specifications are contained in ICAO documentation and implemented by most country regulators.

Specific designs features include:

- A solid aluminum shell immediately around the memory units.

- A thick layer of high-temperature insulation (usually dry silica).

- A thick stainless steel or titanium outer shell.

- Heat-resistant and bright-colored external paint.

Units are designed and well-tested to withstand force extremes of around 3,400G, temperatures of 2000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,100 degrees Celsius), and survive the pressure equivalent of submerging at 20,000 feet for 30 days. Note that there could be differences in these requirements between the different country regulators. Black boxes are usually located near or in the aircraft’s tail section. This is typically the part of the aircraft to suffer the least damage in a crash. Most flight recorders will contain a battery to facilitate continued recording even if the aircraft power fails.

Get all the latest aviation news right here on Simple Flying

Easy to locate

Survival is not the only important aspect – it is also essential to be able to locate the black box. Bright red or orange coloring helps make it stand out on the ground. It does not emit any form of signal when on the ground – it is assumed that the crash site has been tracked in any case. The external housing may be badly damaged, but the design should have protected the critical contents (as can be seen from the picture below of the actual recorder recovered from the crash of West Air Sweden flight 294 in 2016).

If located in water, most black boxes are equipped with a locator beacon that emits an ultrasonic ping to help searchers find it. This should work for up to 30 days and at extreme depths (up to 20,000 feet). There has, of course, been discussion about updating black boxes with more modern technology available today. In particular, the possibility of transmitting real-time data from the aircraft. The technology for this is available, but changes will be expensive and take time (especially for safety-critical areas).

As it is, the reliability and survivability of the black box is excellent. There are very few cases of devices being unrecoverable (apart from underwater instances where they can’t be detected) or the data being unusable.

Feel free to discuss more about black box design, survivability, or specific cases of recovery in the comments section.