I had never read a bodybuilding magazine before I started working at one. It was December 1992, I was a broke-ass graduate student, and out of pure luck landed a part-time copyediting job at Muscle & Fitness.

I knew a few of the biggest names—Arnold and Franco and Lou Ferrigno—but had no sense of the history of the iron game, and how for the past century it had influenced our notion of what a guy could look like.

My ignorance prevented me from understanding that I had arrived at a key moment.

Once I realized how much there was to know, I was hooked. I now have a shelf full of books covering the rich, strange, and often hilarious history of the pursuit of muscle.

Even better, I have friends who’ve seen more and know more, and were happy to share their insights.

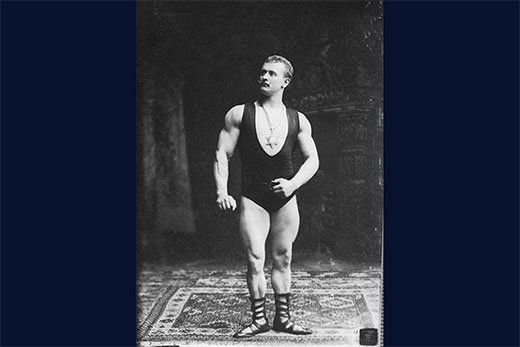

Eugen Sandow

In the beginning, there was Sandow.

Born Friedrich Muller in Prussia in 1867, he hit the strongman circuit in his late teens, saw a world of previously unimagined opportunities, changed his name, and obliterated the idea that massive strength required a massive belly.

This dude had abs long before anyone thought to call them that.

To say he’s the father of modern bodybuilding actually diminishes just how amazing Sandow was. He toured in a Ziegfeld production. He trained the king of England.

Related Video:

When he staged the first bodybuilding contest in 1891, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the guy who created Sherlock Holmes, was one of the judges. After his stage performances in New York, wealthy women paid for the chance to go backstage and feel his muscles.

But he was, first and foremost, phenomenally strong.

In 1893, at the height of his fame, he agreed to a physical examination by Dr. Dudley Sargent of Harvard, himself a pioneer in exercise science. Sargent measured Sandow at a somewhat ordinary 5-foot-8, 180 pounds. (Like many bodybuilders since, Sandow claimed to be both taller and heavier than he was.)

Perhaps to make up for being smaller than advertised, he knelt down and asked the 175-pound Sargent to step onto his open palm. With little apparent effort, he stood up, keeping his arm straight, and set Sargent down on a table.

Related: What and When You Should Eat to Build Muscle

Sargent declared him “the perfect man” (the anecdote is from a book called Houdini, Tarzan, and the Perfect Man, by John F. Kasson), and to this day Sandow’s image is used on the Mr. Olympia trophy.

Charles Atlas

Sandow at his peak was one of the most famous people in the English-speaking world. Nobody capitalized more on the standard he set than Angelo Siciliano, who, like Sandow, invented a manlier name to advance his career.

Atlas claimed to be a former 97-pound weakling.

After getting sand kicked in his face, he remade his body, using his Dynamic Tension system, and became so big and intimidating that no bully dared mess with him again.

It’s a story every guy growing up in the second half of the twentieth century knew by heart, thanks to the full-page ads in the back of our comic books.

Was any of it true? Nobody knows, and nobody cares. It was the original fitness infomercial, and for generations of skinny boys it was their only hope of a more muscular future.

Related: The Workout All Skinny Guys Have Been Waiting For

Siciliano was a well-known weightlifter by 1922, when he won the title of “America’s most perfectly developed man” and changed his name. That year he went into business selling a routine of body-weight exercises combined with health and lifestyle advice.

Neither the exercises nor the advice were thought to be original at the time, but Atlas, thanks to his charisma and the marketing chops of his business partners, made it his own.

Although he died in 1972, his course is still available at dynamictension.com.

John Grimek

The 1936 Olympics are best known for Jesse Owens showing up his host, Adolf Hitler, by winning four gold medals. John Grimek, America’s heavyweight weightlifting champion, was barely a footnote, finishing a distant ninth.

Grimek had no real love for Olympic weightlifting, and little interest in training for it. He also had no interest in gaining the kind of bulk that would’ve made him a world champion—at 195 pounds, he was usually the lightest heavyweight—and when he dieted down to the next-lowest weight class he lost too much strength.

Related: The 6 New Bodybuilding Rules Every Man Should Memorize

What he was good at, and what he apparently loved, was the slower lifts, and the muscle he gained from doing them.

As a bodybuilder he was undefeated, winning six titles between 1939 and 1949.

When he won Mr. America for the second straight time, in 1941 (a day after competing in weightlifting), “he stood so far ahead of the others that a rule was adopted preventing previous winners from entering the contest,” according to John Fair in Muscletown, USA: Bob Hoffman and the Manly Culture of York Barbell.

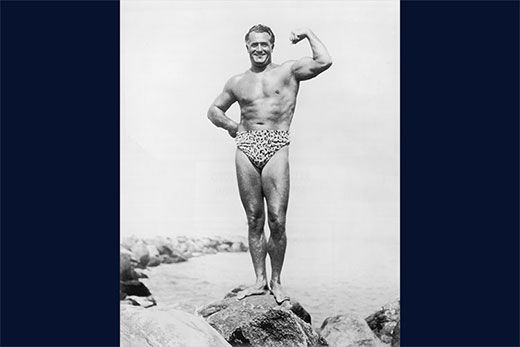

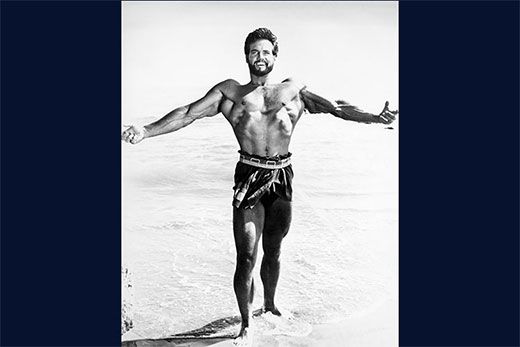

Steve Reeves

Reeves finished behind Grimek in the 1941 Mr. America and the 1949 Mr. Universe, but became far better known, and much more influential.

I don’t think it’s controversial to say he was the greatest bodybuilder of the pre-steroid era.

For one thing, at 6-foot-1, he was taller than most, with smaller bone structure.

For another, he looked like a movie star long before he became one.

Related: Is Cardio Necessary For Super-Low Body Fat?

But that’s not to say he wasn’t strong AF. Various reports say that he could deadlift 400 pounds while holding the bar with just his fingertips, and that he once did a barbell clean with 225 pounds from his knees.

He also knew how to push himself.

According to Grimek, Reeves took a year off lifting before the 1950 Mr. Universe, and won the contest after just seven weeks of training. Without steroids.

Larry Scott

History barely remembers the bitter rivalry between the two great muscle entrepreneurs of the second half of the twentieth century.

Bob Hoffman of York Barbell had the initial advantage. He was the dominant voice of Olympic weightlifting, and some of the greatest lifters in American history were his employees. He also published Strength & Health magazine, which celebrated strength and athleticism above all else.

His rival, Canadian-born Joe Weider, saw the greater potential of bodybuilding, and the potential of exercises like the squat and bench press to build those muscles.

At his height, Weider controlled both the means and the ends of bodybuilding. He published magazines like Muscle & Fitness and Flex, and used them to promote the Mr. Olympia contest, which he and his brother Ben created in 1965.

Enter Larry Scott, who won the first two Mr. Olympia titles.

At 5-foot-7, Scott weighed just over 200 pounds, with 20-inch arms that looked even bigger on his relatively narrow frame.

Perhaps most important, he was among the first champion bodybuilders known to use the newly available anabolic steroids.

Since steroids preferentially pack muscle onto the upper torso—the lats, traps, pecs, deltoids, and upper arms—he was able to overcome his genetic limitations to produce a physique that helped change what we think a well-developed body should look like.

Related: How to Tell If Someone Is Using Steroids

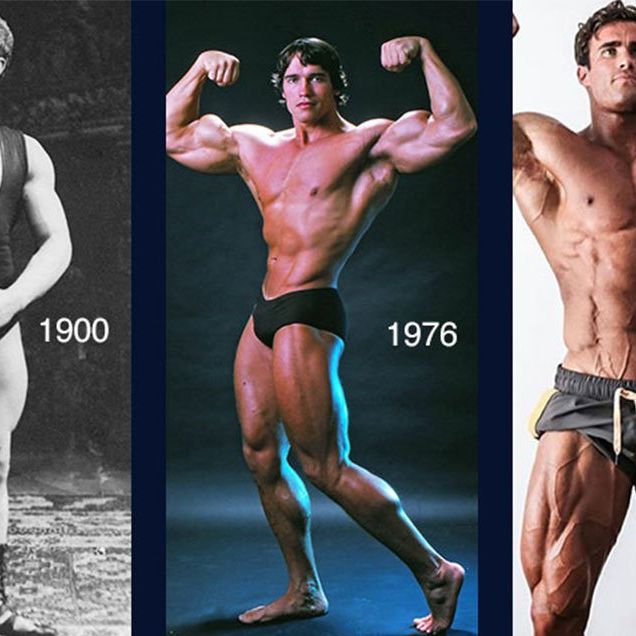

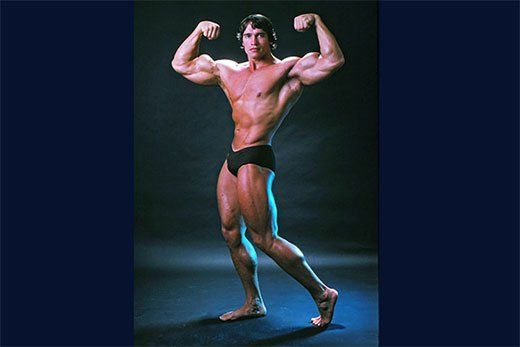

Arnold Schwarzenegger

Arnold wasn’t the biggest or best-conditioned bodybuilder of the late 1960s. Sergio Oliva, a Cuban émigré, was bigger, and guys like Bill Pearl looked leaner and sharper.

But Arnold was the first one that people I knew talked about.

I can remember kids at school describing him in a talk-show appearance. “He looks big and strong when he’s flexing,” someone opined. “But when he sits down, his muscles all sag and he just looks deformed.”

It’s easy to look back at pictures of Schwarzenegger and recognize the features that set him apart, and the skillful ways he displayed them. But his greatest feat was being Arnold.

“Arnold took bodybuilding out of the sideshow category by sheer force of his personality,” says TC Luoma, editor-in-chief of t-nation.com. “His charisma and his never-before-seen physique even appealed to the average guy whose only experience with weights was with a Nautilus machine.”

Once we’d seen that physique, and gotten a sense of the showman who built it, it changed our perception of both muscularity and masculinity.

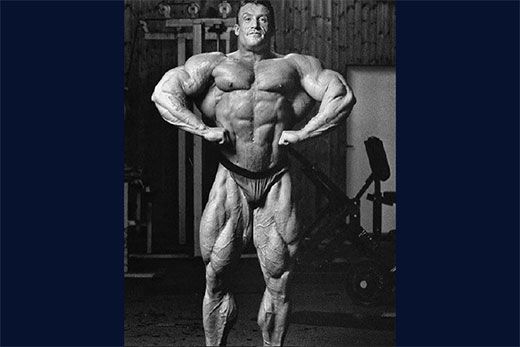

Dorian Yates

Arnold was 6-foot-2, 235 pounds at his peak. That gave him a body-mass index of 30.2, which means the most iconic bodybuilder in history, a guy known as an enthusiastic steroid user, was slighter than Dwayne “the Rock” Johnson, a former pro wrestler.

The fact actors and athletes could look like bodybuilders meant that bodybuilders themselves had to look like something else. By the 1990s, Luoma says, “contests were largely won by whoever dared to make the greatest amount of anabolic steroids.”

And not just steroids.

By the early ’90s bodybuilders were adding insulin and human growth hormone to the mix, giving them “that superhuman ballooned look,” says Bryan Krahn, a writer and physique coach.

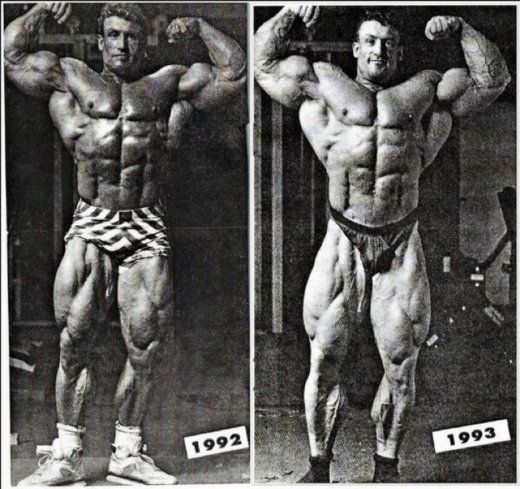

If you want an example of how much the standards changed, and how quickly, consider these photos of Dorian Yates, who won Mr. Olympia six straight times, beginning in 1992.

Between the ’92 and ’93 contests, he went from 241 to 257 pounds, which looked like much more than 16 pounds on a guy who’s listed as 5-foot-10. (For what it’s worth, I’m 5-10, and on the one time I saw him at the Weider offices, I thought he was a couple inches shorter than me.)

The difference from one year to the next was paradigm-changing.

To compete with Yates, bodybuilders had to be impossibly huge and impossibly lean.

The polypharmacy required for that look produced a body count of top-level competitors who died in their 20s or 30s, and several others who survived but eventually required kidney transplants.

Yates, fortunately, is not just alive, but also apparently healthy and still in good shape.

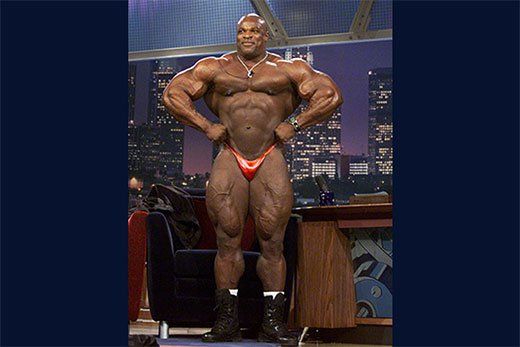

Ronnie Coleman

Way back in the 1930s, John Grimek resisted gaining the 20 to 30 pounds he would’ve needed to be an Olympic weightlifting champion. He liked his waistline just the way it was.

Seventy years later, the pursuit of freaky mass led to an epidemic of “GH gut” (growth hormone gut) among top bodybuilders, including eight-time Mr. Olympia Ronnie Coleman.

A police officer in Arlington, Texas, Coleman was by all accounts one of the most genetically gifted individuals in the history of the sport. Whether he was ever truly “natural”—as he claimed he was at the beginning of his bodybuilding career—is open to debate.

Related: Does It Matter How Fast You Lift?

When he started serious training in 1989, he was 5-11, 215. By 1990, when he entered his first amateur contest, he was up to 230. He reportedly competed at 297 in the early 2000s.

That kind of mass, with no visible body fat, should’ve been impossible. He had muscles in places where the rest of us don’t even have places.

Coleman, along with his contemporaries and their successors, “passed from somewhat freakish to otherworldly freakish,” Luoma says. “Their bodies, too, began to resemble each other. Whereas bodybuilders in Arnold’s day were often known for having a body part that was more developed or particularly aesthetic, this new genre all looked the same.”

That opened the door for something different.

Calum von Moger and Steve Cook

Von Moger (shown above) is a 25-year-old Australian who invites comparisons to Schwarzenegger.

Cook (shown below) is a 31-year-old former college football player who invites comparisons to Steve Reeves, aiming for the smallest possible waist and equal circumference of the neck, upper arms, and calves.

Both are popular on social media, and neither has expressed any interest in gaining the kind of size it would take to compete with the mass monsters for the major bodybuilding titles. It’s their physiques that lifters today are more likely to aspire to.

“I don’t know any sane person who wants to look like” the top pro bodybuilders, Krahn says.

“They’re too big, too bloated, and chicks don’t dig it. Even the juice monkeys I know want to look ‘aesthetic,’ which is code for a Steve Cook physique—someone with muscle and abs and good teeth and hair who likely gets laid a lot. Hell, I’m old and married, and I want to look like Steve Cook.”

The Future Of Physiques

Luoma thinks today’s young and ambitious gym rats are less inspired by any individual and more influenced by CrossFit, MMA, and even superhero movies.

“All three represent something that the bodybuilders don’t have: functionality,” he says.

If he’s right, it means the world of muscle is returning to its roots, when circus strongmen like Eugen Sandow drew crowds by lifting heavy things, or when John Grimek competed in weightlifting and bodybuilding on consecutive days, or when Steve Reeves’ contemporaries—the stars of the Muscle Beach scene in the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s—dazzled audiences with acrobatic displays that simultaneously showed off their strength, agility, athleticism, and, yes, amazing physiques.

Bodybuilding eventually became a static pursuit, with the goal of looking good in still pictures rather than showing what those overbuilt bodies could do.

But today, it appears, muscles are back on the move.

Lou Schuler is an award-winning journalist and contributing editor to Men’s Health. Check out his new book Strong: Nine Workout Programs for Women to Burn Fat, Boost Metabolism, and Build Strength for Life, with coauthor Alwyn Cosgrove.