The first I heard about Amadeus was a characteristically vivid telephone call from the legendarily foul-mouthed director John Dexter (at that time head of productions at the Metropolitan Opera in New York). “Callow? What d’you know about Mozart?” “Well, er, I …” “You’d better find out, hadn’t you, because you’re about to fucking well play Mozart in Peter fucking Shaffer’s new play, aren’t you?” An hour later it was in my hands, in my bedsit in Hampstead.

I read the play with some surprise. I was not taken aback by the story of Mozart’s alleged poisoning at the hands of Antonio Salieri (which I knew from Rimsky-Korsakov’s operatic setting of Pushkin’s play on the same theme), nor by the scatological language; what amazed me was what I took to be the crudeness of the dramaturgy. Mozart appeared to be defined by his giggle; the emperor Joseph II – the most powerful monarch of the second half of the 18th century – simply repeated his catchphrase (“Well, there it is!”); and Mozart’s wife, Constanze, used words such as “delish”.

I was just 30, had only been acting for seven years, mostly on the fringe, and I had highfalutin ideas about what constituted good playwriting. This was not it. Even the central idea – that the God-fearing, diligent and honourable Salieri felt mocked by the extraordinary talent with which the botty-slapping, shit-shanking Mozart had been so undeservedly endowed, and took it upon himself to take revenge on the young genius on behalf of mediocrities everywhere – seemed contrived and inflated. When I finished reading the play, I threw it across the room. “How very disappointing,” I thought. I would obviously have to turn it down.

And then I remembered a scene quite near the beginning of the play, when Mozart had just arrived at court and Salieri graciously welcomed him with a little tune in his honour. After the court have retired and the two composers are left together, Mozart plays the march from memory: “That doesn’t really work, does it? Did you try … ?” and within 30 seconds, he has turned the anodyne jingle into “Non più andrai” from The Marriage of Figaro. I realised that the script contained the essence of the play in a single perfect theatrical gesture, and longed to play the scene.

Shaffer’s plays – especially The Royal Hunt of the Sun and Equus – had made a huge impact on me: the ideas were riveting, but it was the theatricality of the presentation that was so overwhelming. In Royal Hunt, he gave us the extraordinary image of Robert Stephens as the sun-god Atahualpa surrounded by great golden petals; in Equus, the naked boy had ridden a steed for which an actor wore a horse’s head and hooves forged from steel. Dexter had directed both productions and now the old team was reuniting. I stilled my doubts and went along to the Savoy Grill in central London to meet Shaffer and Dexter.

Their relationship was one of pretty rough banter. For some reason, Dexter addressed the writer as Ruby; Shaffer, while remaining courteous and deferential, would flick away his insults with slightly narrowed eyes and a telling barb. It was like being in an undiscovered play by Sheridan. Shaffer took to calling Dexter “Rose”. “Rose?” snarled Dexter. “Yes,” he said, pleasantly, “as in Rose, thou art sick.” Dexter grunted appreciatively. He was full of plans: who should design the play, when it should be done, how we should approach the music, the terms on which we’d offer the production to the National Theatre, if we did. Somehow, inexplicably, I had became part of the “we” who were doing the offering, though neither Dexter nor Shaffer had ever seen me act.

The big question, of course, was who should play Salieri. Great names were mentioned and shot down: Plummer, McCowen, Olivier. “Paul Scofield would be wonderful,” said Shaffer, clearly not for the first time. “Wouldn’t he?” He turned to me, pointedly. All through the conversation he had been catching my eye meaningfully, as if to say, “You see?” I said: “Oh yes – such gravitas.” “It’s the fucking gravitas that’s the problem,” said Dexter. “We’ll have to knock that out of her.” Eventually he needed to go, and Shaffer and I were left alone. Shaffer turned to me and said: “It’s been like this for years. But it’s getting worse.”

All this was deeply surprising to me. I had only met Dexter once, for a kipper breakfast at the Savoy when he offered me a part in another play, which never happened. Despite his not having seen me act, my playing this dazzling role in the latest play by the most commercially successful playwright in the English language seemed to be a fait accompli. After Dexter left, Shaffer relaxed considerably. Clearly he had been having a hard time of it with him. And Shaffer needed someone to talk to. At that moment we became friends for life. From time to time I would bump into him in a foyer or at a restaurant and his despair and frustration were unconcealed. “I shall go mad, my dear, quite, quite mad,” he said. “John won’t commit to anything. He says we’ll put it off for a couple of years. Well, we won’t. I know my plays: they have their moment.” And then one day he let me know that Dexter and he had sundered their long partnership; Shaffer, the most urbane of men, had uncharacteristically thrown himself on the floor, screaming with rage, he told me, because Dexter had demanded a percentage of the returns from the play whenever and wherever it was done.

Enter Peter Hall, who had convinced Shaffer without too much difficulty that the play should be done at the National Theatre, and that he should direct it. The somewhat Wagnerian atmosphere changed to something more in keeping with Mozart’s 18th century: it was all charm, courteous exchanges and assurances. And, miraculously, I was still playing Mozart, even though Hall too had never seen me act. The cast was soon announced – Scofield, gravitas and all, Felicity Kendal, with whom I had previously acted, and a peerless gang of players from the National’s Olivier Theatre company.

Hall’s style, though there was no question who was in charge, was much more collegiate than Dexter’s. In fact, I was astonished at how flexible the process was: Shaffer seemed open to any suggestion, the text was infinitely malleable. This pleased me – I was a veteran of the fringe, where we always made plays like that. Shaffer would bring me presents every day of a delicious new line or a startling new scene. I thrashed about trying to fill, with some sort of lived life, the outline of the part Shaffer had so vividly sketched. Felicity and I had a glorious time romping around, though I was worried I was close to burlesque. “You gave a very brave performance,” Hall had said to me after the read-through, “but I have to believe at all times that you wrote the overture to Figaro.” I wrestled with this inspired piece of directing; finally I think I got it.

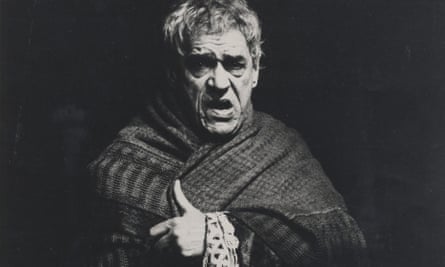

Scofield, noble and charismatic in a rumpled sort of way, effortlessly dominated the rehearsal room. He was not especially happy, and went about his secret work on the part, with occasional volcanic eruptions when we glimpsed the majesty of what he might be about to deliver. And that unique voice, that mighty diapason, a series of organ stops covering more octaves than seemed humanly possible, would occasionally be deployed. (Once, alarmingly, he roared at me after I had irritatingly suggested that the scene needed a new line: “Not from me, baby,” he shouted, “you monster.”) But for the most part he seemed to be waiting.

However flexible the text might be, at the core of the play were certain theatrical gestures in which Shaffer’s innate genius for communicating with an audience was plain to see. Salieri’s sudden transformation from ancient dying lunatic to elegant young court musician, Mozart being haunted on his deathbed by his jealous rival, above all Mozart’s rewriting of Salieri’s pedestrian march – all of these were there from the start, and they were never going to change. But it was hard to judge whether the play was really working. It seemed somehow lightweight, thin, despite all the fine language, melodrama and music.

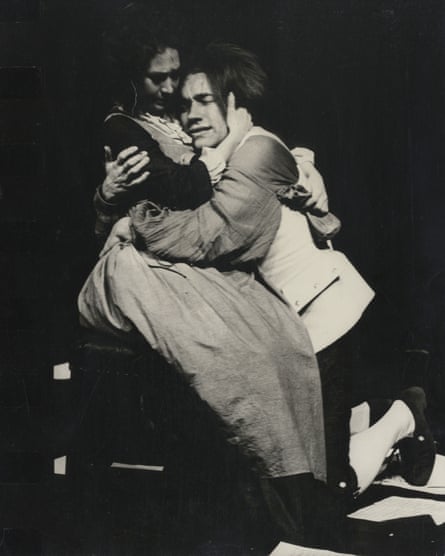

Scofield didn’t attend the technical rehearsals: “My feet are killing me,” he confided in me. The dress rehearsals were fine, efficient and energised, but a bit mechanical. So the first preview knocked us sideways. We hadn’t reckoned on the audience’s hunger for the piece. Perhaps Scofield had. I had seen him physically expand as he came on stage for the dress rehearsals, but now, in front of an audience, he had become some sort of an animal, a panther or a tiger, prowling around in absolute contact with the audience, whose longing for him was almost embarrassing: positively carnal. It felt as if they had been aching for a very long time for the sort of full-blooded theatricality the play so brilliantly purveyed. They totally submitted to Scofield’s sublime embodiment of embittered mediocrity, they wept for Mozart’s piteous demise, they took it on the chin when Scofield addressed his last words to them with a kind of terrible complicity, which mingled intimacy with contempt: “Mediocrities everywhere, now and to come: I absolve you all.” And the audience’s response was the same at every performance over the next two years at the National Theatre, except for the night Margaret Thatcher came, when the entire audience looked at her. She came backstage. “Mozart wasn’t like that,” she said to Hall. “I think you’ll find, prime minister, that he was,” Hall replied. “I don’t think you heard me,” she said. “He wasn’t like that.”

The reviews were, to put it mildly, mixed. The bad ones, and some were very bad, created an aura of controversy around what was otherwise an unassailable hit – the combination of Shaffer, Scofield and Mozart had guaranteed that. But in the end, what made it extraordinary – what has made it extraordinary whenever it has been revived – is the visceral theatrical instinct of its author. He received his knighthood late in the day; critics never admitted him to the league of Pinter or Stoppard. But audiences raced to the theatre to see what he had wrought. He was a supreme storyteller who perfectly inhabited his medium. The film of Amadeus – by far the most satisfactory of all attempts to make movies of his work – is a sumptuous experience, whose worldwide success transformed Mozart from a composer respected by the general public into one deeply loved by them, but if you want to taste the essence of Shaffer, go and see the play.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion