Abstract

Yalom (1980) identified three forms of isolation: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and existential. This chapter focuses primarily on existential isolation, both as an existential reality and as a subjective experience. Existential isolation refers to the inherent unbridgeable gap between any two beings and the impossibility of knowing with certainty how anyone else experiences the world. The chapter begins with discussion of existential isolation as an existential reality and how awareness of it can be threatening to a species that relies upon shared social validation for meaning and psychological security. The chapter then examines the consequences and potential benefits of confronting existential isolation, considers how existential isolation relates to other existential concerns, and reviews empirical research on the topic. The chapter concludes with a discussion of ways in which psychotherapy could help clients develop resources to manage the anxiety associated with awareness of existential isolation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Existential isolation

- Identity

- Meaning

- Freedom

- Death

- Terror management theory

- Meaning maintenance

- Existential loneliness

1 Introduction

Therapists and mental health workers have recognized the prevalence of social disconnection for a long time, and the consequences of disconnection are well documented (e.g., Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). Chapters “Isolation, Loneliness and Mental Health” and “Social Prescribing: A Review of the Literature” will primarily focus on the most commonly researched form of isolation, loneliness. While some researchers might dispute the degree to which loneliness constitutes an existential concern, it is recognized as a universal experience (McGraw, 1995; Perlman, 2004). Moreover, affiliation, social connection, and belongingness constitute key sources of meaning that are threatened by loneliness (Van Tilburg et al., 2019), and loneliness has been found to be associated with lower perceived meaning (Hicks et al., 2010).

Nevertheless, isolation is rarely discussed in an existential context, especially among empirical psychologists. Unlike other existential concerns (e.g., death, meaning), research on existential isolation has remained relatively sparse. Yet recent efforts have begun to investigate the subjective experience and awareness of existential isolation and compare its consequences to those of other forms of isolation (e.g., Helm, Greenberg, et al., 2019a; Pinel et al., 2017).

The present chapter will focus on existential isolation, both as an existential reality and as a subjective experience. This chapter will start with a discussion of the definition of existential isolation as described by Yalom’s (1980) Existential Psychotherapy. It will consider how awareness of existential isolation can be threatening to a species that relies upon shared social validation for meaning and psychological security. The chapter then examines the consequences and potential benefits of confronting existential isolation. The chapter then considers how existential isolation relates to other existential concerns, reviews empirical research on the topic, and concludes with a discussion of potential ways in which psychotherapy could help alleviate existential isolation in those negatively affected by it.

2 Existential Isolation

Existential psychotherapist Irvin Yalom (1980) describes three types of isolation: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and existential. Intrapersonal isolation “is a process whereby one partitions off parts of oneself” (p. 354). In severe cases, this process can refer to clinical disorders (e.g., dissociative disorders) but can also refer to any fragmentation of the self, such as instances in which a person suppresses their own thoughts or desires, mistrusts their own judgments, or knowingly acts inauthentically.

Yalom (1980) notes that interpersonal isolation, “generally experienced as loneliness, refers to an isolation from other individuals” (p 353). Interpersonal (i.e., between person) isolation is most frequently conceptualized as social isolation or as loneliness. Social isolation (e.g., Child & Lawton, 2017) is understood as an objective lack of relationships or contact with others (i.e., one is physically separated from others). Though, as Yalom argues, interpersonal isolation is most often experienced as loneliness, which refers to the subjective and distressing feeling associated with dissatisfaction with one’s social contacts (e.g., Peplau & Perlman, 1982), it should be noted that interpersonal isolation can also be experienced positively as in solitude, which often is viewed as a restorative experience and a venue for creative or religious experiences (see Coplan & Bowker, 2014; Mansfield et al., 2019).

The third type of isolation is existential isolation, which “refers to an unbridgeable gulf between oneself and any other being. It refers, too, to an isolation even more fundamental—a separation between the individual and the world” (Yalom, 1980, p. 355). When a person becomes aware of their existential isolation, they may feel as if no one understands their perceptions, that they are alone in their subjective experience (Pinel et al., 2017). Yet if interpersonal isolation refers to “between person” separation, then wouldn’t existential isolation fall into this category? Indeed, in Yalom’s extended discussion of existential isolation, he refers to it as a “vale of loneliness” (p. 356) and suggests interpersonal and existential isolation are so closely related that the boundaries between them are semipermeable. Moreover, the subjective experience of the two forms of isolation “may feel the same and masquerade for one another” (p. 355).

Thus, what makes existential isolation unique? Yalom (1980) proposes that existential isolation does not ultimately stem from interpersonal relationships but rather exists as an existential reality (i.e., it flows from the givens of existence). In other words, all humans across time and space must contend with existential isolation (e.g., Sullivan et al., 2012). Insofar that humans can only experience the world through their personal sensory organs and cannot read another’s mind, no matter how close two individuals get, there always exists “an unbridgeable gulf” between people preventing them from truly knowing firsthand the experience of another (Mueller, 1912). Becker (1971) describes awareness of existential isolation as emerging out of developmental processes; as we develop a theory of mind, we realize that “we come into contact with people only with our exteriors—physically and externally; yet each of us walks around with a great wealth of interior life, a private and secret self” (p. 28).

This awareness of one’s inherent isolation is particularly problematic for a species that continuously relies upon abstract symbolic representations of the world (e.g., Becker, 1971; Berger & Luckmann, 1966; Rank, 1945). From an existential perspective, there is no inherent meaning or purpose to life, and thus humans invest in socially constructed and maintained symbolic conceptions of reality that imbues life with meaning, order, and permanence (Becker, 1971; Greenberg et al., 1986; Kierkegaard, 1981). These symbolic organizations can range from microlevel (e.g., feeling confident in one’s basic conceptions and interpretations of reality) to macrolevel (e.g., abstract symbolic belief systems such as national or religious identity) conceptions (e.g., Arndt et al., 2013). Importantly, because these abstract representations are ultimately fictions, their validity depends upon social validation and agreement.

Many theories across disciplines underscore the importance of socially shared and constructed bases of psychological processes (e.g., Asch, 1952; Barrett, 2017; Becker, 1971; Cooley, 1964; Echterhoff et al., 2009; Festinger, 1954; Mead, 1934). For example, Festinger’s (1954) theory of social comparison asserts that the validity of our personal beliefs depends upon shared belief by similar others. Similarly, research on reflected appraisals argues that people learn about themselves most directly from others rather than from introspection or self-observation (Vazire, 2010). Becker (1971), and later terror management theory (Greenberg et al., 1986; Routledge & Vess, 2019), argues that socially shared belief systems ultimately address core fundamental human concerns (e.g., How did I get here? What is the meaning and purpose of my life?).

Awareness of one’s existential isolation threatens to thwart the protective nature of these symbolic constructions of reality. Existential isolation is the awareness that one is ultimately alone in their interpretation of reality (i.e., one can never truly know with certainty the subjective experiences of another), thus undermining the protective function of socially constructed symbolic conceptions (Pinel et al., 2004). For example, imagine a devout Christian is listening to a lecture from a Buddhist monk on the cycles of reincarnation and finds herself intrigued and comforted by these notions. Meanwhile, other members of her congregation are reacting with horror and disbelief. The listener realizes she is having very different reactions than those around her and, even more concerning, having reactions that may be at odds with her current belief system. She becomes aware her perceptions may not be shared by those around her, and if the doctrine of another religion is more comforting than her own, which should she believe? In essence, awareness of her existential isolation (i.e., uniqueness of experience) threatened the foundation of her socially constructed beliefs. A wide variety of research finds that when people’s sense of shared reality is undermined, it can leave them feeling uncertain and vulnerable (e.g., Asch, 1951; Echterhoff et al., 2009).

3 Confronting Existential Isolation

“We are all lonely ships on a dark sea. We see the lights of other ships—ships that we cannot reach but whose presence and similar situation affords us much solace. But if we can break out of our windowless monad, we become aware of the others who face the same lonely dread. Our sense of isolation gives way to a compassion for the others, and we are no longer quite so frightened. An invisible bond unites individuals who participate in the same experience—whether it be a life experience shared in time or place (e.g., attending the same school) or simply as a member of an audience at some event.”

- Irvin Yalom, Existential Psychotherapy

Confronting existential concerns is not an easy or comfortable task (Heidegger, 1927; Kierkegaard, 1981). Like existential threats more broadly, awareness of one’s existential isolation induces the potential for negative affect, whether consciously or unconsciously (Sullivan et al., 2012). Yalom (1980) writes, “The experience of existential isolation produces a highly uncomfortable subjective state and…is not tolerated by the individual for long. Unconscious defenses ‘work on it’ and quickly bury it—outside the purview of conscious experience” (p. 362). Thus, similar to proximal defenses in terror management theory that serve to push death thoughts out of conscious awareness (see Burke et al., 2010, for a review), defense processes operate to bury awareness of isolation.

The primary mechanism of isolation denial is relational in nature (Fromm, 1963; Yalom, 1980), which can include relationships with one’s work (e.g., becoming a workaholic), orgiastic states (e.g., engaging in religious or sexual states), or conformity (e.g., merging or fusing with a group, investing in interpersonal relationships). Work on identity fusion (e.g., Swann et al., 2012), which occurs when people experience a visceral feeling of oneness with a group, is an example of extreme isolation denial tendencies. The act of “fusion [with another person, group, cause, country, or project] eliminates isolation in a radical fashion—by eliminating self-awareness” (Yalom, 1980, p. 380).

Though Yalom (1980) cautions that while no relationship can eliminate isolation entirely (though fusion may give the impression one has), aloneness can be shared in such a way that “love compensates for the pain of isolation” (p. 363). Echoing sentiments expressed by Martin Buber (1970), Yalom argues that mature, authentic relationships marked by empathy, perspective taking, and reciprocity best serve to assuage one’s existential isolation. Through even a brief relational encounter, the self is altered because it internalizes the encounter; “it becomes an internal reference point, an omnipresent reminder of both the possibility and reward of a true encounter” (Yalom, 1980, p. 396). If the relational encounter is positive and authentic, the internalized experience serves as a tempering of existential anxiety (Yalom, 1980). While relationships can perhaps bridge the existential gulf momentarily, and may facilitate growth, it is ultimately incumbent upon the individual to bear the pangs of existential stress “resolutely” (Camus, 1955; Heidegger, 1927; Hobson, 1974; Kierkegaard, 1981; Yalom, 1980). Through engaged and directed confrontation with one’s existential isolation, one may develop a tolerance to be able to cope with one’s situation.

Other thinkers have also argued that confronting existential isolation can be a process toward growth though the meaning of growth is often poorly articulated (see Ettema et al., 2010, for a review). Generally, a confrontation with existential isolation is thought to have the potential to foster three types of growth. These are personal growth, in which an individual’s potential might be actualized (e.g., Mayers et al., 2005; Park, 2006); interpersonal growth, where one’s relationships deepen and feelings of intimacy are heightened (e.g., Lindenauer, 1970; May & Yalom, 2000); or spiritual growth, where one relates to himself or herself in a more transcendent mode (e.g., Collins, 1989). By acknowledging that one is existentially isolated, a person may also discover their internal resources and strength in the face of this fact. The development of such resilience may be an important first step in living with existential isolation in an adaptive manner. It has also been suggested that acceptance of one’s existential predicament can lead to increased empathy and perspective taking toward others who are in the same situation.

One potential problem with this perspective is that it benefits those who already have adequate resources in place to confront their existential anxiety—a rich get richer, poor get poorer dilemma. Individuals who are already able to relate to others in secure and mature ways are most able to confront and tolerate their isolation. In contrast, those without these resources struggle to find safety and security (e.g., Plusnin et al., 2018).

4 Existential Isolation in the Day-to-Day

Individuals are often isolated from others and from parts of themselves, but underlying these splits is an even more basic isolation that belongs to existence—an isolation that persists despite the most gratifying engagement with other individuals and despite consummate self-knowledge and integration.

- Irvin Yalom, Existential Psychotherapy

As we have argued so far, and as Yalom articulates in the quote above, existential isolation is an ever-present concern, persisting despite our interpersonal connections and irrespective of level of self-knowledge. Experiences with existential threats are part of the normal range of experience of the average person within a given culture (e.g., Sullivan et al., 2012; Tillich, 2000). Thus, confronting existential concerns is not necessarily pathological or the result of a neurotic condition. However, the average person, at least in Western cultures, is not likely to be aware of, or to be able to understand when, existential concerns are influencing thoughts, emotions, and behavior.

Factors that May Contribute to Keeping Existential Isolation Out of Consciousness

Social psychological research has identified a variety of cognitive biases that may combat awareness of existential isolation. For example, confirmation bias is the tendency to interpret and attend to information that supports one’s own position and to ignore information that does not support one’s attitudes (Landau et al., 2004; Nickerson, 1998). Research on the false consensus effect (Ross et al., 1977) suggests that people typically overestimate the number of other people who share their beliefs and attitudes. In both cases, these projective heuristics lead to the sense that one’s subjective beliefs are accurate and shared by others, thus reducing the likelihood that one will become aware of their existential isolation. An American conservative watching Fox News and an American liberal watching CNN are both likely to feel like their views are shared much more than they really are.

Other work suggests that as we develop close and intimate relationships, we naturally tend to assume the other person shares our internal perspectives. For example, work with people in satisfying and stable relationships reveals that they tend to perceive similarities with their partners even when these similarities are not evident in reality (e.g., Murray et al., 2002). These egocentric assumptions help the individual to feel understood and satisfied in their relationship, but ultimately, these assumptions are distortions and serve a protective function against isolation awareness. Other research suggests that people will even change their own views to coincide with others in uncertain situations (Asch, 1951; Echterhoff et al., 2009), thus perhaps ignoring their own intuitions to avoid confronting their fundamental isolation.

Anxiety buffers may also contribute to keeping awareness of existential isolation at bay. Theories of psychological defense (e.g., terror management theory, anxiety buffer disruption theory, meaning maintenance model; see Hart, 2014) propose that humans are motivated to protect themselves from potentially anxiety-evoking threats by investing themselves in a variety of buffers including close relationships, self-esteem, and cultural worldviews. From these perspectives, anxiety buffers function to allow us to operate with relative psychological equanimity in the face of existential concerns (e.g., inevitable death, inherent isolation). Research has found that strong anxiety buffers ameliorate anxiety and are associated with better health. For example, research has found that high self-esteem (either dispositionally or experimentally elevated) attenuates the threat of death (e.g., Greenberg et al., 1992; Harmon-Jones et al., 1997) and is associated with greater mental and physical health (e.g., Kernis, 2005). Along these lines, it is reasonable to expect strong anxiety buffers to also mitigate the threat of existential isolation.

Factors that May Contribute to a Greater Propensity to Experience Existential Isolation

In contrast to the various mechanisms and processes that serve to keep existential out of focal awareness, other factors may contribute to a greater propensity to experience fundamental isolation. Aside from the more straightforward proposition that weak anxiety buffers (e.g., low self-esteem, weak interpersonal relationships, doubting one’s cultural worldviews) would therefore contribute to elevated existential isolation, cultural factors are also likely important.

Researchers have identified a range of dimensions upon which cultures vary. One commonly researched dimension is individualism-collectivism (Triandis, 1995). Individualist societies (e.g., the United States) tend to value the individual over the group, and people tend to prioritize their personal goals over the goals of others. Collectivist societies (e.g., Japan) tend to value in-groups (e.g., family, organization) over individual needs. In individualistic cultures, people tend to think of themselves as discrete and tend to use others as a source of social comparison to confirm their uniqueness (Cross et al., 2011; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). In collectivist cultures, people tend to think of themselves in relational terms (e.g., friend, coworker) and tend to use others as a way to determine if they are fulfilling their relational obligations (Cross et al., 2011). A society’s level of individualism may influence the degree to which its members are likely to experience existential isolation. Insofar that individualistic people see themselves as distinct from others and place greater value on their personal experiences and goals while downplaying the perspectives of others, they should be more likely to become aware of their fundamental disconnection from others. In contrast, members of collectivistic cultures, who are constantly aware of the needs and perspectives of others, should be less likely to become aware of their fundamental disconnectedness (Pinel et al., 2020).

5 Relating Existential Isolation to Other Existential Concerns

Many thinkers have argued that existential concerns are interrelated and awareness of one may activate another (e.g., Pyszczynski et al., 1990; Tillich, 2000; Yalom, 1980).

Death

Yalom (1980) argues awareness of one’s own death ultimately leads an individual toward a confrontation with their fundamental isolation and writes, “Each of us enters existence alone and must depart from it alone” (p. 9). Though a person may be surrounded by family and friends, though others may die at the same time or for the same cause, “at the most fundamental level dying is the most lonely human experience” (Yalom, 1980, p. 356). By this reasoning, contemplating one’s inevitable death leads one to a realization of their inherent isolation. In the reverse direction, death is arguably the highest order, or most distal source, of existential threat (Pyszczynski et al., 1990; Tillich, 2000). Without the threat of nonbeing, other existential threats would lose their impact. Thus, any confrontation with existential isolation should ultimately lead one toward death-related concerns.

Meaning

An existential framework suggests that humans live in an inherently meaningless and absurd world. Yet humans strive to create and maintain systems of meaning, which provide buttresses against existential angst. A confrontation with meaninglessness leads the individual to feel as though the world is chaotic and human endeavors are pointless (e.g., Kierkegaard, 1981; Tillich, 2000). Awareness of one’s existential isolation may undermine one’s sense of meaning (Kuperus, 2018). Given that systems of meaning are ultimately substantiated by confidence in social validation, awareness that one can never truly have their subjective feelings validated by another leaves the structures of meaning on insecure foundations. In this sense, the threats of existential isolation and meaninglessness may have a bidirectional relationship.

Freedom

The existential concern of freedom refers to the ability to choose one’s path at any moment (e.g., Sartre, 2001), leading humans to cope with the responsibility of self-creation. Awareness of authorship implies that others are therefore not responsible for one’s actions, and thus, one must contend with the isolation of self-creation (e.g., Yalom, 1980). In other words, awareness of choice (and the corresponding responsibility) leaves the individual vulnerable to existential isolation because the individual is alone in having to make and live with their choices.

Identity

The concern of identity refers to the inability to have full knowledge of oneself and arises through the courage to be part of groups or through affirmation processes. These processes reflect differences in personal and social identity (e.g., Castano et al., 2004). Personal identity refers to identification with the self, restricted to one’s body and being. Social identity, in contrast, extends beyond the self and refers to identification with a group or community. Social identity theorists (e.g., Hogg & Mahajan, 2018; Tajfel, 1978) argue that social groups in part function to assuage existential concerns. Yet as discussed, effectively merging with a social group may be thwarted by awareness of one’s inherent separateness from others. Moreover, Yalom (1980) discusses a primary consequence of self-awareness, and inward focus is an awareness of one’s existential isolation. Insofar that the problem of identity illuminates inward focus and requires an individual to self-create, it should also activate a potential for awareness of one’s existential isolation.

6 Empirical Research on Existential Isolation

Assessment Measures

There has been very little research focusing on existential isolation compared to other existential concerns (i.e., death, meaning) though recently, researchers have begun to study this experience empirically. Until recently, most papers considering existential isolation focused on qualitative experiences of patients in palliative care or with psychological disorders (e.g., Ettema et al., 2010; Kazanjian & Choi, 2013; Mayers et al., 2002; Mayers & Svartberg, 2001). There have been two prominent exceptions to this trend. Mayers and colleagues (Mayers et al., 2002) developed an Existential Loneliness Questionnaire (ELQ) to assess the experience among women with HIV, and Pinel and colleagues (Pinel et al., 2017) developed a trait Existential Isolation Scale (EIS), which measures the degree to which individuals regularly feel as though others do not or cannot understand their subjective perceptions and experiences. This scale has also been adapted to assess state or in-the-moment experiences of existential isolation.

The ELQ has multiple items that specifically reference HIV diagnoses and was found to correlate very highly with general loneliness, depression, and purpose in life in a sample of women with HIV, suggesting the questionnaire may assess a construct that overlaps with other constructs, at least in clinical samples. The EIS scores showed small to moderate correlations with general loneliness, demonstrate stability over time, and showed adequate concurrent and discriminant validity with related constructs. The majority of the research highlighted below focuses on work utilizing the Pinel et al. (2017) scale.

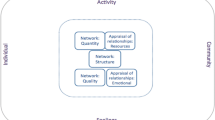

Correlates of Existential Isolation

Empirical work has examined the extent to which awareness of existential isolation relates to a variety of social psychological phenomenon in an attempt to underscore the utility of assessing isolation in an existential sense rather than only interpersonally. One such body of research has found that existential isolation is indeed associated with a weakened anxiety buffer (Helm et al., 2019b). As reviewed above, humans have various anxiety buffers (i.e., cultural worldviews, self-esteem) in place that buffer against potential anxiety-inducing threats (for a review, see Burke et al., 2010). Terror management research has found that when these anxiety buffers are threatened, they no longer prevent our consciousness from contemplating death, and death thoughts become more accessible in consciousness.

Emerging work, however, has begun to focus on baseline death-thought accessibility, which is conceptualized to be indicative of a weak or fragmented anxiety buffer (e.g., Hayes et al., 2010). Researchers reasoned that if existential isolation threatened the foundations of our anxiety buffers (i.e., undermined the social validation of these symbolic conceptions), then it would be associated with elevated death thoughts. Indeed, existential isolation was found to be associated with elevated death-thought accessibility and that reminding participants of their existential isolation increased death thoughts compared to control primes (Helm et al., 2019b). Moreover, this work found that existential isolation was associated with less importance of one’s national identity and lower self-esteem. Importantly, the relationship between existential isolation and death thoughts could not be explained by loneliness though the relationship between loneliness and death thoughts could be explained by their mutual relationship to existential isolation.

Other work has examined how existential isolation may relate to attachment orientations. Guided by research that found loneliness to be associated with insecure attachment (e.g., Hazan & Shaver, 1987), researchers proposed that individuals who have a history of relationships with unavailable, rejecting, and inconsistently attentive attachment figures should be high in existential isolation. Consistent with these propositions, researchers found existential isolation to predict both attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety (Helm et al., 2020a) though existential isolation was more related to attachment avoidance than to attachment anxiety. Interestingly, those with secure attachment consistently reported low existential isolation, mirroring Yalom’s (1980) assertion that mature relationships may buffer existential isolation.

In similar research focusing on how existential isolation may impact community relationships, Pinel et al. (2020) found participants with higher existential isolation were less likely to endorse humanitarian values (e.g., “one should be kind to all people”) and prosocial behaviors (e.g., “I donate to local causes”). Complementing the finding above that existential isolation predicts less identification with one’s group, these works suggests that those who are most aware of their existential isolation may also feel less integrated with, and supportive of, their local communities.

Other work (Park & Pinel, 2020) examined how existential isolation may vary culturally. In a study conducted in South Korea, they found average levels of existential isolation to be lower than those found in the United States. Moreover, existential isolation was negatively correlated with collectivism, such that the greater one’s collectivist values, the lower their reported existential isolation. In a different series of studies conducted in the United States (Helm et al., 2018), existential isolation was found to be higher among men than women, and this difference was explained by differences in communal value endorsement, mirroring the cross-cultural findings. These studies complement research that finds self-reported loneliness to be lower in more collectivist cultures (e.g., Heu et al., 2019).

Given that feelings of existential isolation are conceptualized as the sense that others do not, or cannot, understand one’s subjective experiences, it makes sense that individuals with nonnormative experiences may report elevated levels of existential isolation (e.g., Kazanjian & Choi, 2013; Mayers & Svartberg, 2001). Yawger and colleagues (Yawger et al., 2020) found that individuals with minority identities (e.g., non-White, nonheterosexual, heavy weightFootnote 1) reported higher existential isolation than their majority identity counterparts (i.e., White, heterosexual, non-heavy weight). In other work examining individuals with nonnormative experiences, Helm and colleagues (Helm et al., 2020b) found that student veterans reported higher existential isolation than did other undergraduate students. Moreover, student veterans who interacted with other veterans at least occasionally reported lower existential isolation than those who rarely interacted with other veterans. These studies suggest that interacting with, or thinking about, individuals with a common identity or shared experience may serve to temper feelings of existential isolation.

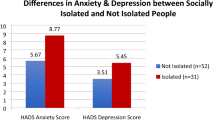

Previous qualitative and conceptual studies on existential isolation have found it to be inherently connected to death awareness, especially among those in end-of-life care (e.g., Bolmsjö et al., 2019). Recent research has also begun to examine the empirical relationship between existential isolation and mental health. Multiple studies have found existential isolation (though some utilizing an indirect assessment) to be correlated with depression (Kretschmer & Storm, 2017; Mayers et al., 2002), stress, and anxiety (Constantino et al., 2019). In another study, Helm and colleagues (Helm et al., 2020a) compared the effects of existential isolation and loneliness on depression and suicide ideation and found them to have independent and unique effects. This study also found existential isolation and loneliness interacted to predict depression, such that individuals who had both elevated existential isolation and loneliness reported an average depression that qualified for mild clinical depression. Thus, individuals who are experiencing multiple types of isolation may be the most prone to mental health concerns.

Taken together, these preliminary research findings suggest there are important antecedents and consequences to the experience of existential isolation. Helm and colleagues (Helm et al., 2019a) recently articulated a state trait existential isolation model, which focuses on how high existential isolation can be a temporary state triggered by a specific situation; it may be context dependent, and it can be experienced consistently over time as a trait. Situations or events that may elicit elevated state existential isolation are likely those where an individual is aware she or he is having a different experience or reaction than others (either from another person or a group). Though this model is theoretical and has not been fully tested, Helm and colleagues (Helm et al., 2019b) found asking participants to write about an existentially isolating event increased state existential isolation. More broadly, it seems likely that the trait form of high existential isolation, because of its chronic nature, is most likely to impact mental health negatively.

7 Implications for Psychotherapy and the Treatment of Existential Isolation

Given the association between existential isolation and poorer mental health and negative affect, it is worth exploring psychotherapy’s utility in alleviating the pangs of existential isolation and its effects on psychological well-being. We can approach existential isolation treatment from two directions. First, we can address existential isolation directly by reducing a client’s propensity to become aware of existential isolation through authentic relationships. Second, we can address existential isolation indirectly by attending to its aftereffects and specifically anxiety and the erosion of meaning.

Yalom (1980) argues that psychopathology can stem from avoiding existential isolation because it can lead to problematic defense mechanisms. One individual might avoid the terror of existential isolation by attempting to fuse with another, losing their sense of self by dominance or subservience to another in a dependent relationship. Another might blindly conform to their in-group and vilify out-groups, denigrating the “other.” Still another might engage in compulsive sexual relationships to heal their sense of aloneness.

The psychotherapist can help the client become aware of maladaptive patterns of behavior stemming from avoidance of existential isolation and assist the client in developing more productive patterns of behavior associated with approaching their existential isolation. Along these lines, Yalom (1980) argues perhaps the most important element of therapy, transcending the therapist’s theoretical orientation, is the therapeutic alliance between the therapist and patient.

Though there is disagreement about precisely defining the therapeutic alliance, it refers to the bond between the client and therapist and a sense of collaboration, warmth, and support (e.g., De Re et al., 2012). Almost 40 years of psychotherapy research has found the therapeutic alliance to be an important aspect of successful treatment, a consistent predictor of therapy outcomes, and one of the core mechanisms in the change process (De Re et al., 2012; Kuutmann & Hilsenroth, 2012). There are many recommendations for the therapist who wants to cultivate authentic relationships with clients. Kaiser (1965) emphasizes the importance of honest communication and a dispositional interest in people, sensitivity to duplicity, and the absence of theoretical views or neuroses that interfere with communication. Sequin (1965) describes a “psychotherapeutic eros” or genuine, nonreciprocal caring for the client’s well-being and growth as essential for authentic connection. Similarly, Rogers (1951, 1980) suggests bringing an attitude of unconditional positive regard, empathy, and authenticity to every client session (see also Norcross, 2010).

Each of these recommendations emphasizes fostering authentic encounters by relating to the client in a genuine, caring fashion. Yalom (1980) maintains that authentic relationships allow the therapist to “enter the patient’s world and experience it as the patient experiences it” (p. 409). Thus, the therapeutic alliance may directly reduce existential isolation via an authentic encounter within the therapy room. Though the therapist-client relationship is temporary, the client can realize from this experience that such genuine connections are possible and enriching. This realization can motivate a client to seek and establish similar authentic connections with others.

Yalom (1980) argued that group therapy sessions can also be valuable for clients to practice recognizing their own and others’ patterns of maladaptive responding to existential isolation (e.g., inauthentic relating) and sharing these perceptions with each other. These group relationships can also improve the quality of future relationships by serving as “dress rehearsals” for new modes of relating.

Drawing from empirical research cited earlier, support groups organized around specific social identities may be particularly useful in directly reducing existential isolation. Though it is impossible to truly bridge the existential gap between human beings, group meetings among individuals who share an identity or experience can help validate their experiences and give the impression that others can understand their experiences. For example, consider the treatment of addiction. Uncomfortable awareness of existential isolation could lead to substance use as a means to alleviate the negative feelings associated with it. Group therapy can serve as a venue for addicts to recognize and discuss their maladaptive patterns of behavior in response to existential angst (Kelly et al., 2020; Rogers & Cobia, 2008). This venue would presumably be additionally helpful for those feeling the pangs of existential isolation because others attending the group have had similar experiences, thus reducing their sense of existential isolation. As quoted above, “an invisible bond unites individuals who participate in the same experience,” and group therapy sessions provide such an experience.

A key issue that drives maladaptive behaviors associated with existential isolation is that people often opt for inauthentic relationships to manage the anxiety and negative affect associated with it, yet these relationships are likely to be ineffective long-term solutions (Kassel, 2010). Cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) focus on modifying unhelpful cognitions and behaviors. Given that clients may have such distorted beliefs about the utility of engaging in inauthentic relationships, a program for altering patterns of thought and behavior that supports more authentic modes of relating may be helpful.

The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP; Barlow et al., 2018; Farchione et al., 2012) is an emotion-focused CBT developed to treat the entire range of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. UP combines the key features of many CBT modalities, including changing maladaptive cognitive evaluations, emotion-based action tendencies, discouraging emotion avoidance, and promoting emotion exposure. In particular, UP emphasizes understanding the nature of emotions (i.e., associated bodily sensations, cognitions, behaviors), the adaptive function of emotions (e.g., anxiety teaches us to be careful), and recognizing and changing maladaptive responses to these emotions. From the perspective of UP, a client’s instinctive reaction to engage in inauthentic relationships to avoid the anxiety of existential isolation might be a maladaptive “emotionally driven behavior.” In addition, the client may have maladaptive beliefs that support this behavior, such as “my partner and I are one; I can lose myself in my partner.” This belief is false because there is no way to eliminate existential isolation no matter how close you become to someone. Therefore, part of the work from a UP standpoint is the identification of these problematic patterns of thought and behavior, understanding the nature and universality of the anxiety associated with existential isolation, and practicing an approach orientation toward these feelings while attempting to relate to other people in a new and authentic way.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 2006; Hayes et al., 2011) is another popular, approach-oriented CBT. ACT focuses on cultivating psychological flexibility through mindful acceptance of emotions and connection with one’s values and taking committed action to live a meaningful life despite emotional difficulties. Like UP, ACT can teach individuals to accept the anxiety associated with existential isolation while simultaneously helping them to respond to it in a more adaptive way. For instance, a client could cultivate mindful acceptance of their anxious response to existential isolation while at the same time choosing to connect with their values (e.g., authenticity) and practice courage and vulnerability as they open up to others in a genuine way.

Both UP and ACT serve to address existential isolation in both direct and indirect ways. As mentioned, UP and ACT facilitate movement away from inauthentic relationships toward authentic relationships. Specifically, beyond the authentic connection possible through a good therapeutic alliance, these cognitive behavioral approaches involve guidance, support, and homework that assists clients in building authentic relationships outside the therapy room, thus providing opportunity to reduce existential in the real world.

Perhaps less obvious, ACT also addresses existential isolation indirectly by addressing the erosion of meaning possibly stemming from existential isolation (Hayes et al., 2011). As mentioned, existential isolation is problematic in that it undermines the social validation that supports one’s worldview. ACT explicitly focuses on connecting a client to their values and fosters their commitment to taking action to live a meaningful life, which can also strengthen a client’s perceived meaning in life and faith in their worldview.

8 Concluding Remarks

Existential isolation is an inherent component of the human condition. It is impossible to know with certainty that anyone else experiences the way you perceive the world or truly understands your subjective experiences. Awareness of one’s existential isolation can threaten the symbolic foundation of our systems of meaning and psychological security. A confrontation with one’s isolation often leads to defensive behaviors aimed at pushing it out of conscious awareness, but many theorists contend that confrontation can ultimately lead to growth. Empirical studies have found that existential isolation relates to a variety of mental health concerns (e.g., depression, suicide ideation), cultural factors (e.g., collectivism), and interpersonal factors (e.g., insecure attachment style, minority status). Treatment considerations should focus on the healing aspects of the therapeutic alliance and the insights offered by recent cognitive behavioral therapies.

Notes

- 1.

Heavy weight status was characterized by individuals with a body mass index (BMI) above 25 (calculated by participant’s height and weight), and those with non-heavy weight status had a BMI at 25 or below (Centers for Disease Control, 2016).

References

Arndt, J., Landau, M. J., Vail, K. E., III, & Vess, M. (2013). An edifice for enduring personal value: A terror management perspective on the human quest for multilevel meaning. American Psychological Association.

Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In H. Guetzkow (Ed.), Groups, leadership, and men: Research in human relations (pp. 177–190). Carnegie Press.

Asch, S. E. (1952). Social psychology. Prentice Hall.

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Sauer-Zavala, S., Latin, H. M., Ellard, K. K., Bullis, J. R., … Cassiello-Robbins, C. (2018). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders. Therapist guide. Oxford University Press.

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made. Macmillan.

Becker, E. (1971). The birth and death of meaning. Free Press.

Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Anchor Books.

Bolmsjö, I., Tengland, P., & Rämgård, M. (2019). Existential loneliness: An attempt at an analysis of the concept and the phenomenon. Nursing Ethics, 26, 1310–1325.

Buber, M. (1970). In W. Kauffman (Ed.), I and thou. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Burke, B. L., Martens, A., & Faucher, E. H. (2010). Two decades of terror management theory: A meta-analysis of mortality salience research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14, 155–195.

Camus, A. (1955). The myth of Sisyphus. The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, 88–91.

Castano, E., Yzerbyt, V., & Paladino, M. (2004). Transcending oneself through social identification. In J. Greenberg, S. L. Koole, & T. Pyszczynski (Eds.), Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 305–319). Guilford Press.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Defining adult overweight and obesity. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html

Child, S. T., & Lawton, L. (2017). Loneliness and social isolation among young and late middle-age adults: Associations with personal networks and social participation. Aging and Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1399345

Collins, W. E. (1989). A sermon from hell: Toward a theology of loneliness. Journal of Religion and Health, 28, 70–79.

Constantino, M. J., Sommer, R. K., Goodwin, B. J., Coyne, A. E., & Pinel, E. C. (2019). Existential isolation as a correlate of clinical distress, beliefs about psychotherapy, and experiences with mental health treatment. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. Advance online publication.

Cooley, C. H. (1964). Human nature and the social order. Schocken Books. (Original work published 1902)..

Coplan, R. J., & Bowker, J. C. (2014). All alone: Multiple perspectives on the study of solitude. In R. J. Coplan & J. C. Bowker (Eds.), The handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone (pp. 3–13). Wiley & Sons.

Cross, S. E., Hardin, E. E., & Gercek-Swing, B. (2011). The what, how, why, and where of self-construal. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 142–179.

De Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., Horvath, A. O., Symonds, D., & Wampold, B. E. (2012). Therapist effects in the therapeutic alliance-outcome relationship: A restricted-maximum likelihood meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 642–649.

Echterhoff, G., Higgins, E. T., & Levine, J. M. (2009). Shared reality: Experiencing commonality with others inner states about the world. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 496–521.

Ettema, E. J., Derksen, L. D., & van Leeuwen, E. (2010). Existential loneliness and end-of-life care: A systematic review. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics, 31, 141–169.

Farchione, T. J., Fairholme, C. P., Ellard, K. K., Boisseau, C. L., Thompson-Hollands, J., Carl, J. R., … Barlow, D. H. (2012). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 43(3), 666–678.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140.

Fromm, E. (1963). Art of loving. Bantam Books.

Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of the need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Public self and private self (pp. 189–212). Springer-Verlag.

Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., Rosenblatt, A., Burling, J., Lyon, D., & Pinel, E. (1992). Assessing the terror management analysis of self-esteem: Converging evidence of an anxiety-buffering function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 913–922.

Harmon-Jones, E., Simon, L., Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & McGregor, H. (1997). Terror management theory and self-esteem: Evidence that increased self-esteem reduces mortality salience effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 24–36.

Hart, J. (2014). Toward an integrative theory of psychological defense. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9, 19–39.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25.

Hayes, J., Schimel, J., Arndt, J., & Faucher, E. H. (2010). A theoretical and empirical review of the death-thought accessibility concept in terror management research. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 699–739.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change. Guilford Press.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. R. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 511–524.

Heidegger, M. (1927). In J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson (Eds.), Being and time. Harper.

Helm, P. J., Rothschild, L., Greenberg, J., & Croft, A. (2018). Explaining sex differences in existential isolation research. Personality and Individual Differences, 134, 283–288.

Helm, P. J., Greenberg, J., Park, Y. C., & Pinel, E. C. (2019a). Feeling alone in your subjectivity: Introducing the state trait existential isolation model (STEIM). Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology, 3, 146–157.

Helm, P. J., Lifshin, U., Chau, R., & Greenberg, J. (2019b). Existential isolation and death thought accessibility. Journal of Research in Personality, 82, 1–14.

Helm, P. J., Jimenez, T., Bultmann, M., Lifshin, U., Arndt, J., & Greenberg, J. (2020a). Existential isolation, loneliness, and attachment in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 159, 1–8.

Helm, P. J., Marchant, D., Arndt, J., & Greenberg, J. (2020b). Experiences of existential isolation amongst student veterans. Manuscript in Preparation.

Heu, L. C., van Zomeren, M., & Hansen, N. (2019). Lonely alone or lonely together? A cultural-psychological examination of individualism-collectivism and loneliness in five European countries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45, 780–793.

Hicks, J. A., Schlegel, R. J., & King, L. A. (2010). Social threats, happiness, and the dynamics of meaning in life judgments. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 1305–1317.

Hobson, R. (1974). Loneliness. Journal of analytic. Psychology, 19, 71–89.

Hogg, M. A., & Mahajan, N. (2018). Domains of self-uncertainty and their relationship to group identification. Journal of Theoretical Social Psychology, 2, 67–75.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 227–237.

Kaiser, H. (1965). Effective psychotherapy: The contribution of Hellmuth Kaiser (L. Fierman). : Free Press.

Kassel, J. D. (2010). Substance abuse and emotion. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12067-000

Kazanjian, C., & Choi, S. (2013). Encountering the displaced child: Applying Clark Moustakas’ concept of existential loneliness to displaced youth. Journal of Global Responsibility, 4, 157–167.

Kelly, J. F., Abry, A., Ferri, M., & Humphreys, K. (2020). Alcoholics anonymous and 12-step facilitation treatments for alcohol use disorder: A distillation of a 2020 Cochrane review for clinicians and policy makers. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 55, 641–651.

Kernis, M. H. (2005). Measuring self-esteem in context: The importance of stability of self-esteem in psychological functioning. Journal of Personality, 73, 1569–1605.

Kierkegaard, S. (1981). In R. Thomte (Ed.), The concept of anxiety. Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1844)..

Kretschmer, M., & Storm, L. (2017). The relationships of the five existential concerns with depression and existential thinking. International Journal of Existential Psychology & Psychotherapy, 7, 1–20.

Kuperus, G. (2018). Beyond the dread of death: Existentialism’s embrace of the meaninglessness of life. Chapter 3. In R. E. Menzies, R. G. Menzies, & L. Iverach (Eds.), Curing the dread of death: Theory, research and practice (pp. 41–56). Australian Academic Press.

Kuutmann, K., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (2012). Exploring in-session focus on the patient-therapist relationship: Patient characteristics, process and outcome. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 19, 187–202.

Landau, M. J., Johns, M., Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Martens, A., Goldenberg, J. L., & Solomon, S. (2004). A function of form: Terror management and structuring the social world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 190–210.

Lindenauer, G. G. (1970). Loneliness. Journal of emotional. Education, 10, 87–100.

Mansfield, L., Daykin, N., Meads, C., Tomlinson, A., Gray, K., Lane, J., & Victor, C. (2019). A conceptual review of loneliness across the adult life course (16+ years). What Works Wellbeing.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253.

May, R., & Yalom, I. (2000). Existential psychotherapy. In R. J. Corsini & D. Wedding (Eds.), Current psychotherapies (6th ed., pp. 273–302). Wadsworth.

Mayers, A. M., & Svartberg, M. (2001). Existential loneliness: A review of the concept, its psychological precipitants and psychotherapeutic implications for HIV-infected women. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 74, 539–553.

Mayers, A. M., Khoo, S., & Svartberg, M. (2002). The existential loneliness questionnaire: Background, development, and preliminary findings. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 1183–1193.

Mayers, A. M., Naples, N. A., & Nilsen, R. D. (2005). Existential issues and coping: A qualitative study of low-income women with HIV. Psychology and Health, 20, 93–113.

McGraw, J. G. (1995). Loneliness, its nature and forms: An existential perspective. Man and World, 28, 43–64.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. University of Chicago Press.

Mueller, J. (1912). Elements of physiology. In B. Rand (Ed.), The classical psychologists: Selections illustrating psychology from Anaxagoras to Wundt (pp. 530–544). Constable & Co. Limited. (Original work published 1834).

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., Bellavia, G., Griffin, D. W., & Dolderman, D. (2002). Kindred spirits? The benefits of egocentrism in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 563–581.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2, 175–220.

Norcross, J. C. (2010). The therapeutic alliance. Chapter 4. In B. L. Duncan, S. D. Miller, B. E. Wampold, & M. A. Hubble (Eds.), The heart and soul of change (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association.

Park, J. L. (2006). Our existential predicament: Loneliness, depression, anxiety, & death (5th ed.). Existential Book.

Park, Y. C., & Pinel, E. (2020). Existential isolation and cultural orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 159, 109891.

Peplau, L. A., & Perlman, D. (Eds.). (1982). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research, and therapy. Wiley.

Perlman, D. (2004). European and Canadian studies of loneliness among seniors. Canadian Journal on Aging, 23, 181–188.

Pinel, E. C., Long, A. E., Landau, M., & Pyszczynski, T. (2004). I-sharing, the problem of existential isolation, and their implications for interpersonal and intergroup phenomena. In J. Greenberg, S. Koole, & T. Pyszczynski (Eds.), Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 352–368). Guilford Press.

Pinel, E. C., Long, A. E., Murdoch, E. Q., & Helm, P. J. (2017). A prisoner of one’s own mind: Identifying and understanding existential isolation. Personality and Individual Differences., 105, 54–63.

Pinel, E. C., Johnson, L. C., Long, A. E., & Helm, P. J. (2020). Existential isolation’s contribution to humanitarianism, sense of community. In And a predilection to do good. Manuscript Under Review.

Plusnin, N., Pepping, C. A., & Kashima, E. S. (2018). The role of close relationships in terror management: A systematic review and research agenda. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22, 307–346.

Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., & Hamilton, J. (1990). A terror management analysis of self-awareness and anxiety: The hierarchy of terror. Anxiety Research, 2, 177–195.

Rank, O. (1945). In J. Taft (Ed.), Will therapy and truth and reality. Alfred A. Knopf.

Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centered therapy. Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, C. (1980). A way of being. Houghton Mifflin.

Rogers, M. A., & Cobia, D. (2008). An existential approach: An alternative to the AA model of recovery. The Alabama Counseling Association Journal, 34, 59–76.

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The false consensus effect: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 279–301.

Routledge, C., & Vess, M. (2019). Handbook of terror management theory. Academic Press.

Sartre, J. (2001). In H. E. Barnes (Ed.), Being and nothingness. Kensington Publishing. (Original work published 1943).

Sequin, C. (1965). Love and psychotherapy. Libra.

Sullivan, D., Landau, M. J., & Kay, A. C. (2012). Toward a comprehensive understanding of existential threat: Insights from Paul Tillich. Social Cognition, 30, 734–757.

Swann, W. B., Jetten, J., Gómez, Á., Whitehouse, H., & Bastian, B. (2012). When group membership gets personal: A theory of identity fusion. Psychological Review, 119, 441–456.

Tajfel, H. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press.

Tillich, P. (2000). The courage to be. Yale University Press. (Original work published 1952).

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Westview.

Van Tilburg, W. A. P., Igou, E. R., Maher, P. J., & Lennon, J. (2019). Various forms of existential distress are associated with aggressive tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences, 144, 111–119.

Vazire, S. (2010). Who knows what about a person? The self-other knowledge asymmetry (SOKA) model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 281–300.

Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

Yawger, G. C., Helm, P. J., Pinel, E. C., Long, A. E., & Scharnetzki, L. (2020). Feeling out of (existential) place: On the cost of non-normative group membership. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Helm, P.J., Chau, R.F., Greenberg, J. (2022). Existential Isolation: Theory, Empirical Findings, and Clinical Considerations. In: Menzies, R.G., Menzies, R.E., Dingle, G.A. (eds) Existential Concerns and Cognitive-Behavioral Procedures. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06932-1_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06932-1_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-06931-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-06932-1

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)