You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Marriage of the Century - A Burgundian Timeline

- Thread starter BlueFlowwer

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 57 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 47 - Edmund the Grouch-back Chapter 48 - Keeping up with the Stewarts Chapter 49 - I'm rather lost at the moment Chapter 50 - We resume events in Burgundy in 1517 Chapter 51 - The Grand Duchy of Brabant - 1505- 1512 Author's update. Regarding the ethics of rewriting chapters Edits update regarding rewamping Final chapter updatePhilip the possible biromantic practical Duke of Burgundy  And he's still bethroted to Catherine of Navarre, so shenanigans all around!

And he's still bethroted to Catherine of Navarre, so shenanigans all around!

Burgundian Kings of Navarre....I like itPhilip the possible biromantic practical Duke of BurgundyAnd he's still bethroted to Catherine of Navarre, so shenanigans all around!

Why not let him marry La Beltraneja..and the french lose.Oh, I have plans for Francis Phoebus in this TL....

*EVIL CACKLE*

Well his only know male lover is Charles, and they were extremely discreet. If it were anything physical it might be quiet during their youth, perhaps at rare alone times.

Given Philip's a duke he's rarely alone, so they are extremely subtle.

Given Philip's a duke he's rarely alone, so they are extremely subtle.

Chapter 15. The Mad War.

Chapter 15. The Mad War.

Anne of France’s regency would be turbulent. Despite her efforts, she faced a coalition of rebels who’s long grievances with the crown erupted in 1485. Ironically one of the leading causes was Philip of Burgundy’s actions in January: A marriage happened.

The estates in Luxembourg had long been twisted around by the dukes of Burgundy and the kings of France. Philip’s father, Charles the Bold, had been duke of Luxembourg since 1467 and after his death left Philip with the duchy. However, due to the events at Nancy, the ducal control of the region was weak. Now with Philip almost at age in 1483 and the King of France dead and a regency for Charles VIII, the Estates at Luxembourg faced a more uncertain future. The death of Peter II, Count of St Pol in 1482 had left the region in the hands of his oldest daughter, Marie of Luxembourg, as a wealthy heiress to her father’s lands. The Estates of Luxembourg sent a delegation to the General Estates in winter 1483 to propose a ducal marriage for Marie. While she was to low a match for Philip himself, his younger brother John was a more suitable bridegroom. The fact that John was even younger than Marie, being six years old, was not a hinderance in the Estates or Philips eyes.

The Estates took the considerations seriously. A match between John and Marie would assure that the county of Brienne, St Pol, Marle and Soissons would once more part of the duchy. It would also leave Philip’s younger brother with his own estates. Marie’s first husband, her uncle Jaques of Savoy had died from a fever two months earlier in 1483. Marie now needed a husband to protect her inheritance and John needed a wealthy wife. Thus under the summer of 1484 a treaty was worked out. Marie would marry John and the Luxembourg title would once more be Burgundian. John would respect his wife’s inheritance and if the marriage was childless the Luxembourg lands would pass to the next heir.

The marriage took place in autumn, the pair had been married by proxy in July. Philip and John left Brussels in September, leaving the duchy in the safe hands of their mother. The ducal entourage included Olivier de La Marche and Guillaume de Baume among others, as well around 700 horsemen and 400 archers, making it a sizable entourage. The brothers arrived in Soissons in October and the pair was married at the cathedral three days later. The new countess was twelve years old and John almost just seven. The young age of the couple meant that the marriage was not consummated until years later. Marie herself was a short and slim girl, blonde haired with thin brows and watery blue eyes.

Compared to her husband, the difference was stark. However, the marriage seemed harmonious at least. John was too young to appreciate his new wife however and Philip had to focus on his duchy. Marie would be left in the care of dowager duchess Margaret until John grew old enough to be a proper husband.

Margaret of York and Marie of Luxembourg, unknown Italian artist

Philip remained in Luxembourg until autumn 1485 with John and Marie. The time was spent meeting with the estates, traveling through various cities and consolidating the ducal (and Marie’s) rule. The terms with the estates went in a very similar fashion to The Great Privilege that had been presented to Burgundy in 1477. The regional courts right would be upheld, the delegates would have their say in the duke’s actions in war, and Philip promised to protect his wife’s inheritance. One change was made to the original marriage treaty; if Marie died without heirs then her estates would fall to the John himself. After much discussion, these changes were accepted, and the ducal couple left for Flanders. John was sworn in as Count of St Pol and Marle, Brienne and Sossions, jure uxoris.

The regents of France took the Burgundian marriage as a provocation, as some of Marie’s inheritance had originally been French fiefs. At Christmas 1485 a delegation arrived from Paris to Antwerp, the message carried a threatening tone to the sixteen-year-old Duke. Philip and Margaret were not willing to declare open war against France, but either one had forgotten the turmoil that the late Louis XI had caused, so a subtler tactic was in order.

Louis of Orléans had tried to seize the regency in 1484, but he had been rejected by the States General of Tours. In return he left for Brittany and the court of Francis II. The Breton heiress was Anne, Francis only living child, at that time seven years old. Louis of Orléans was still married to his sterile and unloved Joan of Valois, but he sent an request for annulment to Pope Innocent VIII (yes, that was his real name).

Louis claimed that his marriage had been illegitimate because it had been forced upon him by the king. His intention for the annulment was to become free and marry Anne of Brittany. Joan of Valois was the sister of Anne of France, causing quite a lot of friction between Louis and his sister-in law.

Philip and Margaret had not forgotten about the favour Louis did them when dealing with the Tudor attempted invasion. Ergo, it was time to repay him. A Burgundian delegation also arrived in Rome, adding voice and strength for the annulment. Richard III of England also sent a letter to the Pope, knowing that a weakened Valois would work in England’s favour. Plus he too had some payback towards Anne.

The annulment was however not granted at that time, but Louis continued to push for it.

Pope Innocent VIII

Louis returned to Paris and tried to have the regency again, resulting in him being arrested and imprisoned in Orléans. Things calmed down momentarily. In spring 1486 the marriage between Charles VIII of France and Isabella of Burgundy finally took place, the bride having turned fifteen as the Treaty of Arras had specified. The relationship between the newlyweds had bloomed ever since they had meet in Paris five years earlier. The young king had come to love his intelligent and pretty bride and she enjoyed the company of her affably fiancé. The marriage in Notre Dame Cathedral was a splendid affair, and for the time, peace reigned.

Duke Philip sent emissaries to the wedding, giving his sister valuable presents. Isabella in return petitioned her husband to keep good tone with Burgundy and it seemed to have paid off, Charles sent joyful greetings to his brother-in law and once more confirmed the match between Philip and his cousin, Catherine of Navarre. Isabella’s estates that she had brought with her was finally put in her control as well.

Marriage of Charles VIII of France and Isabella of Burgundy

However, revived hostilities occurred in France in autumn of 1486. Pope Innocent VIII had, after almost two years of petitions from Louis of Orléans, granted the annulment that Orléans had long desired. The marriage between his and Joan of Valois was declared null and void in September of 1486. The poor Joan left Orléans in shame and returned to Paris. Louis left once more for Brittany, making his suit for Anne of Brittany again. The nine-year-old heiress was still a valuable prize. But Francis II had other plans for his duchy.

The marriage proposed by Edward IV, former king of England, had vanished with the king’s death. The princesses had been declared bastards by Richard III after the failed Tudor invasion, seeing how his nieces could be used against him. The rumours about Eleanor Talbot had been more spread after Edward’s death and it would result in the Titulus Regulus that had been introduced to the english parliament. Elizabeth of York had been shipped off to Portugal after the arrival of Joanna of Portugal, she had been married to Manuel, duke of Beja in 1484. Anne had been placed in a nunnery to take holy orders and Catherine had been married off to Thomas Howard, the son of the Duke of Norfolk, one of Richard III’s staunchest supporters.

Richard had after 1484 suggested another english bride for Francis, his niece Elizabeth de La Poole, the daughter of Elizabeth of York, duchess of Suffolk. The duke of Brittany had accepted the match and Elizabeth arrived in Nantes in March 1485. The marriage of Elizabeth and Francis was nothing surprising, the new duchess did not leave a great impact personally. However, she had success in the primary duty of a consort: the succession. In 1486, two months after Louis arrived in Brittany, Elizabeth gave birth to a son. The infant, named Jean (for the old Montfort dukes), was immediately named Count of Montford and given the titles at his christening.

Louis of Orléans still wanted to marry Anne of Brittany, knowing that she still stood a chance of inheriting her father’s duchy. Child mortality was a risky business after all.

Francis felt much safer with a son and he thus allowed the marriage between Anne and Louis, even if the girl was not yet ten years old. Anne of Brittany was now duchess of Orléans at her tender age.

With the marriage between Orléans and Brittany, the threat towards Anne of France and the regency became crystal clear. Francis raised his standards along with Louis and the conflict turned from manipulations to force of arms. The Duke of Angouleme, the Prince of Orange and Alain d’Albret joined the cause against the regents.

By 1487 two factions had formed, the Orléans party and the Bourbon party. The Orléans had backers: the king of England and Maximilian of Austria, who had no reason for helping the king of France. Richard III sent a force of 6, 000 men to Brittany, with around thousand archers. They were commanded by Richard Ratcliffe, a able military commander. Burgundy also provided funds, even if it was discreet. The French royal troops had swiss and Italian mercenaries in their service. The commander of the French army was Louis la Trémoille.

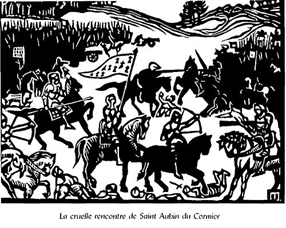

The Battle of Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier in June would decide the outcome of the tension between the Crown and the Orléans-Brittany party. The forces were evenly matched, both amounted to 15,000 each.

The battle initially went in favour of the royal forces, the Orléans party being fragmented and having a hard time to fight efficiently, but the tide turned after Jacques Galliota was killed by the Prince of Orange’s forces. It would be the english longbows that decided the outcome, the sky was said to have been black with falling arrows. The Breton forces would use their cavalry very efficiently, breaking the royal line. The losses to the forces would be hard, around 9,000 men is said to have died, when the Orléans party lost less than 2000 men.

The final blow was when Louis La Trémoille died. The commander had, in a effort to regain the command of the panicked royal forces come within reach of the english archers. Richard III had given Ratcliffe a clear objective in the battle when the english army had left for Brittany: Kill the commanders. Ratcliffe spotted his opponent and immediately ordered several rains of arrows at him. The tactic paid off, Trémoille and several of his captains died in the dense hail.

With the commander and several other officers’ dead the battle was quickly won.

It had been a devastating victory for the Orléans party. However, the regency of Charles VIII ended not much later, leaving the new king with a weakened political power. For Charles one joy occurred in 1487; Isabella of Burgundy was pregnant.

The result of the victory resulted in the Treaty of Verger in 1488. The duke’s strengthened their autonomy against the crown, the crown would also remove their forces on the ducal territories. Anne of France and Peter, duke of Bourbon would leave the court and return to Bourbon. The marriage of Anne of Brittany and Louis of Orléans was recognized by the king.

Charles VIII of France got one good thing out of 1488. Isabella of Burgundy gave birth to a son, named Charles (the king refused to name the baby Louis) on 5th July. The birth of a new Dauphin would be the only victory that year. Four more royal children would be born; Jean in 1490, a stillborn daughter in 1492, princess Anne in 1495 and princess Philippa in 1498.

Anne of France’s regency would be turbulent. Despite her efforts, she faced a coalition of rebels who’s long grievances with the crown erupted in 1485. Ironically one of the leading causes was Philip of Burgundy’s actions in January: A marriage happened.

The estates in Luxembourg had long been twisted around by the dukes of Burgundy and the kings of France. Philip’s father, Charles the Bold, had been duke of Luxembourg since 1467 and after his death left Philip with the duchy. However, due to the events at Nancy, the ducal control of the region was weak. Now with Philip almost at age in 1483 and the King of France dead and a regency for Charles VIII, the Estates at Luxembourg faced a more uncertain future. The death of Peter II, Count of St Pol in 1482 had left the region in the hands of his oldest daughter, Marie of Luxembourg, as a wealthy heiress to her father’s lands. The Estates of Luxembourg sent a delegation to the General Estates in winter 1483 to propose a ducal marriage for Marie. While she was to low a match for Philip himself, his younger brother John was a more suitable bridegroom. The fact that John was even younger than Marie, being six years old, was not a hinderance in the Estates or Philips eyes.

The Estates took the considerations seriously. A match between John and Marie would assure that the county of Brienne, St Pol, Marle and Soissons would once more part of the duchy. It would also leave Philip’s younger brother with his own estates. Marie’s first husband, her uncle Jaques of Savoy had died from a fever two months earlier in 1483. Marie now needed a husband to protect her inheritance and John needed a wealthy wife. Thus under the summer of 1484 a treaty was worked out. Marie would marry John and the Luxembourg title would once more be Burgundian. John would respect his wife’s inheritance and if the marriage was childless the Luxembourg lands would pass to the next heir.

The marriage took place in autumn, the pair had been married by proxy in July. Philip and John left Brussels in September, leaving the duchy in the safe hands of their mother. The ducal entourage included Olivier de La Marche and Guillaume de Baume among others, as well around 700 horsemen and 400 archers, making it a sizable entourage. The brothers arrived in Soissons in October and the pair was married at the cathedral three days later. The new countess was twelve years old and John almost just seven. The young age of the couple meant that the marriage was not consummated until years later. Marie herself was a short and slim girl, blonde haired with thin brows and watery blue eyes.

Compared to her husband, the difference was stark. However, the marriage seemed harmonious at least. John was too young to appreciate his new wife however and Philip had to focus on his duchy. Marie would be left in the care of dowager duchess Margaret until John grew old enough to be a proper husband.

Margaret of York and Marie of Luxembourg, unknown Italian artist

Philip remained in Luxembourg until autumn 1485 with John and Marie. The time was spent meeting with the estates, traveling through various cities and consolidating the ducal (and Marie’s) rule. The terms with the estates went in a very similar fashion to The Great Privilege that had been presented to Burgundy in 1477. The regional courts right would be upheld, the delegates would have their say in the duke’s actions in war, and Philip promised to protect his wife’s inheritance. One change was made to the original marriage treaty; if Marie died without heirs then her estates would fall to the John himself. After much discussion, these changes were accepted, and the ducal couple left for Flanders. John was sworn in as Count of St Pol and Marle, Brienne and Sossions, jure uxoris.

The regents of France took the Burgundian marriage as a provocation, as some of Marie’s inheritance had originally been French fiefs. At Christmas 1485 a delegation arrived from Paris to Antwerp, the message carried a threatening tone to the sixteen-year-old Duke. Philip and Margaret were not willing to declare open war against France, but either one had forgotten the turmoil that the late Louis XI had caused, so a subtler tactic was in order.

Louis of Orléans had tried to seize the regency in 1484, but he had been rejected by the States General of Tours. In return he left for Brittany and the court of Francis II. The Breton heiress was Anne, Francis only living child, at that time seven years old. Louis of Orléans was still married to his sterile and unloved Joan of Valois, but he sent an request for annulment to Pope Innocent VIII (yes, that was his real name).

Louis claimed that his marriage had been illegitimate because it had been forced upon him by the king. His intention for the annulment was to become free and marry Anne of Brittany. Joan of Valois was the sister of Anne of France, causing quite a lot of friction between Louis and his sister-in law.

Philip and Margaret had not forgotten about the favour Louis did them when dealing with the Tudor attempted invasion. Ergo, it was time to repay him. A Burgundian delegation also arrived in Rome, adding voice and strength for the annulment. Richard III of England also sent a letter to the Pope, knowing that a weakened Valois would work in England’s favour. Plus he too had some payback towards Anne.

The annulment was however not granted at that time, but Louis continued to push for it.

Pope Innocent VIII

Louis returned to Paris and tried to have the regency again, resulting in him being arrested and imprisoned in Orléans. Things calmed down momentarily. In spring 1486 the marriage between Charles VIII of France and Isabella of Burgundy finally took place, the bride having turned fifteen as the Treaty of Arras had specified. The relationship between the newlyweds had bloomed ever since they had meet in Paris five years earlier. The young king had come to love his intelligent and pretty bride and she enjoyed the company of her affably fiancé. The marriage in Notre Dame Cathedral was a splendid affair, and for the time, peace reigned.

Duke Philip sent emissaries to the wedding, giving his sister valuable presents. Isabella in return petitioned her husband to keep good tone with Burgundy and it seemed to have paid off, Charles sent joyful greetings to his brother-in law and once more confirmed the match between Philip and his cousin, Catherine of Navarre. Isabella’s estates that she had brought with her was finally put in her control as well.

Marriage of Charles VIII of France and Isabella of Burgundy

However, revived hostilities occurred in France in autumn of 1486. Pope Innocent VIII had, after almost two years of petitions from Louis of Orléans, granted the annulment that Orléans had long desired. The marriage between his and Joan of Valois was declared null and void in September of 1486. The poor Joan left Orléans in shame and returned to Paris. Louis left once more for Brittany, making his suit for Anne of Brittany again. The nine-year-old heiress was still a valuable prize. But Francis II had other plans for his duchy.

The marriage proposed by Edward IV, former king of England, had vanished with the king’s death. The princesses had been declared bastards by Richard III after the failed Tudor invasion, seeing how his nieces could be used against him. The rumours about Eleanor Talbot had been more spread after Edward’s death and it would result in the Titulus Regulus that had been introduced to the english parliament. Elizabeth of York had been shipped off to Portugal after the arrival of Joanna of Portugal, she had been married to Manuel, duke of Beja in 1484. Anne had been placed in a nunnery to take holy orders and Catherine had been married off to Thomas Howard, the son of the Duke of Norfolk, one of Richard III’s staunchest supporters.

Richard had after 1484 suggested another english bride for Francis, his niece Elizabeth de La Poole, the daughter of Elizabeth of York, duchess of Suffolk. The duke of Brittany had accepted the match and Elizabeth arrived in Nantes in March 1485. The marriage of Elizabeth and Francis was nothing surprising, the new duchess did not leave a great impact personally. However, she had success in the primary duty of a consort: the succession. In 1486, two months after Louis arrived in Brittany, Elizabeth gave birth to a son. The infant, named Jean (for the old Montfort dukes), was immediately named Count of Montford and given the titles at his christening.

Louis of Orléans still wanted to marry Anne of Brittany, knowing that she still stood a chance of inheriting her father’s duchy. Child mortality was a risky business after all.

Francis felt much safer with a son and he thus allowed the marriage between Anne and Louis, even if the girl was not yet ten years old. Anne of Brittany was now duchess of Orléans at her tender age.

With the marriage between Orléans and Brittany, the threat towards Anne of France and the regency became crystal clear. Francis raised his standards along with Louis and the conflict turned from manipulations to force of arms. The Duke of Angouleme, the Prince of Orange and Alain d’Albret joined the cause against the regents.

By 1487 two factions had formed, the Orléans party and the Bourbon party. The Orléans had backers: the king of England and Maximilian of Austria, who had no reason for helping the king of France. Richard III sent a force of 6, 000 men to Brittany, with around thousand archers. They were commanded by Richard Ratcliffe, a able military commander. Burgundy also provided funds, even if it was discreet. The French royal troops had swiss and Italian mercenaries in their service. The commander of the French army was Louis la Trémoille.

The Battle of Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier in June would decide the outcome of the tension between the Crown and the Orléans-Brittany party. The forces were evenly matched, both amounted to 15,000 each.

The battle initially went in favour of the royal forces, the Orléans party being fragmented and having a hard time to fight efficiently, but the tide turned after Jacques Galliota was killed by the Prince of Orange’s forces. It would be the english longbows that decided the outcome, the sky was said to have been black with falling arrows. The Breton forces would use their cavalry very efficiently, breaking the royal line. The losses to the forces would be hard, around 9,000 men is said to have died, when the Orléans party lost less than 2000 men.

The final blow was when Louis La Trémoille died. The commander had, in a effort to regain the command of the panicked royal forces come within reach of the english archers. Richard III had given Ratcliffe a clear objective in the battle when the english army had left for Brittany: Kill the commanders. Ratcliffe spotted his opponent and immediately ordered several rains of arrows at him. The tactic paid off, Trémoille and several of his captains died in the dense hail.

With the commander and several other officers’ dead the battle was quickly won.

It had been a devastating victory for the Orléans party. However, the regency of Charles VIII ended not much later, leaving the new king with a weakened political power. For Charles one joy occurred in 1487; Isabella of Burgundy was pregnant.

The result of the victory resulted in the Treaty of Verger in 1488. The duke’s strengthened their autonomy against the crown, the crown would also remove their forces on the ducal territories. Anne of France and Peter, duke of Bourbon would leave the court and return to Bourbon. The marriage of Anne of Brittany and Louis of Orléans was recognized by the king.

Charles VIII of France got one good thing out of 1488. Isabella of Burgundy gave birth to a son, named Charles (the king refused to name the baby Louis) on 5th July. The birth of a new Dauphin would be the only victory that year. Four more royal children would be born; Jean in 1490, a stillborn daughter in 1492, princess Anne in 1495 and princess Philippa in 1498.

Last edited:

Looks like it’s time for Burgundy and Louis and other French dukes to align in a new League of Public Wheal

Last edited:

And Richard got payback for the attempted Tudor rebellion.

Not so happy now are you Anne?

Not so happy now are you Anne?

Now I’m certain on massiv who’s Duchy is but is there any way Louis can make his territory in orleans and his wife’s in Brittany’s contiguous? So that there’s no separation.

Well if baby Jean dies or has no issue, Anne is the next heirress. A Orléans and Brittany duchy would be cool.

Maybe not so likely but Orléans would have to fight to get it where both territories to connect which would be fun to see  I used this map as a reference.

I used this map as a reference.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duchy_of_Bar

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duchy_of_Bar

Next chapter is about Catherine of Navarre and Burgundy. And then the real fun starts!

Nice chapter. But...

Do you mean "autonomy"? Anatomy is to do with your body.

e duke’s strengthened their anatomy against the

Do you mean "autonomy"? Anatomy is to do with your body.

Nice chapter. But...

Do you mean "autonomy"? Anatomy is to do with your body.

Thanks, I edited it now.

I would really be happy to read that.Next chapter is about Catherine of Navarre and Burgundy. And then the real fun starts!

Chapter 16. Burgundy 1485-91.

Chapter 16. Burgundy 1485-91.

While Charles VIII was not happy over the outcome, Philip of Burgundy certainly was. The hard years of 1477-80 had been repaid in kind. The duke could concentrate on consolidate his various realms without worrying about French meddling. The regency had ended on his seventeenth birthday in 1486 and the duke could exercise his power properly. His house was in order, his brother John had turned eleven years old, showing himself to be an athletic and promising youngster, little Margaret, now nine, a charming girl. His sister-in law Marie blossomed into a bright young lady, enjoying the company of the dowager duchess. Now it was time for Philip to get a proper duchess of his own and in spring of 1486, Catherine of Navarre left Pamplona, biding farwell to her brother and mother, Magdalena of France for the last time.

The King of Navarre, Francis Phoebus, had been betrothed to the second daughter of Isabella and Ferdinand, infanta Ana of Castile. However, the arrangements for the match would drag along for many years, as either side had different terms for the match. The king’s marriage in 1491, however, would blindside pretty much everyone and become the final nail in the coffin of Navarre’s independence.

-Source: Phoebus the Dim – The last king of Navarre, Margaret Elijah Watson.

Catherine of Navarre arrived in Amiens in July 1486. Her travel had taken her trough France, from Bordeaux, Poitiers, Orléans and into Paris. Catherine and her entourage stopped to rest for over a week and to bring the greetings of Navarre for the new king. The promised dowry from France was also entrusted to her, being a big sum of 170, 000 crowns. Catherine also meet her sister-in law Isabella and Anne of France. All three ladies spend a pleasant time together, seeming to get well along. After Paris, the Navarre company left for Amiens.

Catherine arrived in late evening in Amiens on 4th July. She was received by the burghers of the city and Philippe Crevecoeur, the ducal governor of Picardy. Similar to her mother-in law’s arrival in 1468, the citizen of Amiens stood outside their houses holding lit torches. The burgers gifted Catherine with a purse of 15 marks and Philippe presented a her with a ruby and emerald brooch from Duke Philip, who had just left Arras the same evening. Catherine and her people were given the townhouse of the bishop of Arras, Jean Jouffroy, to rest after the journey. The next evening, she got two visitors, the dowager duchess Margaret and countess Marie. Their first meeting, as court etiquette demanded, included kneeling in silence in solemn respect. Afterwards the ladies dined in private. Margaret seemed very pleased with Catherine, both her manners and charm.

At the time of her marriage the eighteen-year-old Catherine was a charming young woman, being around 5,7 feet tall with golden brown hair and grey-brown eyes. She had a creamy complexion and thin arched brows with a straight nose.

Catherine of Navarre, duchess of Burgundy, made in 1488

Two days later Philip arrived in Amiens. Catherine was acclaimed the duchess of Burgundy by the bishops of Arras and the members of the Estates who had arrived with the Duke. The marriage was celebrated the day afterwards, the ceremony taking place in the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Amiens (Notre-Dame d’Amiens) Compared to the private wedding of Charles the Bold and Margaret of York, this was a full blow spectacle. As the previous one had been Charles’s third marriage it was understandably.

Notre-Dame d’Amiens

The city set was set to greet its new duchess with the same glorious splendour as her mother-in law had gotten years earlier. The spectacles of biblical stories, the music from the best Flemish composers, the fireworks in the night sky and tournament between the greatest (and most glittering) knights of the duchy; all in total to showcase the splendour of the duchy to the world. Bishops and churchmen leading great processions at evening, holding candles and swinging thuribles waving burning incense. Richly dressed merchants from every kingdom in Europe had gathered in the city, showing off their wealth and of the duke.

A fashionable lady, Catherine arrived at the cathedral on horseback (a beautiful white mare given by Philip) clad in a richly decorated gown of cloth of gold, and a short-sleeved overrobe of blue velvet embroidered with gold. Her hair was loose and a small net with pearls was attached. The charming duchess had a joyful demeanour, a fresh breath of air after troublesome years. The marriage had gotten off to a great start and the ten whole days was spent in celebration and festivities by all in Amiens; the new duchess had been received with love by her husband and her new subjects.

After the wedding feasts the everyday work of the low countries began anew. Most members of Catherine’s entourage left, a handful remained, her six ladies among others. Philip left Amiens to travel to Aachen, both for religious reasons and business. Catherine chose to accompany her husband. The point of the trip to Aachen was to meet up with Maximilian of Austria, who was to be elected king of the romans in the cathedral. Philip had ambitions for his duchy and Maximilian was in need (as he often was) of money. Margaret of York were as usual left to manage the duchy in his absence.

One notable item Philip took with him to Aachen was a coronet owned by his mother Margaret. It had been given by Charles the Bold at the wedding, the coronet itself trimmed with pearls, precious stones and enamelled white roses. The presentation of the dowager’s crown to one of the oldest cathedrals in Europe, constructed by Charlemagne, by the king of Romans’ brother-in law carried strong implications. Aachen was the traditional crowning place of the Holy Roman Emperors and the old emperor, Frederick III, was ailing. The ascension of Maximilian became imminent, as the king of the romans was the title of the imperial successor.

Crown of Margaret of York, Aachen Cathedral

The main reason for the meeting between Philip and the Maximilian was to secure the future election of Maximilian as Holy Roman Emperor. Philip brought a considerable amount of money and valuables with him to Aachen for that purpose.

The marriage of Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy had since leaving Burgundy in 1478 flourished. Both spouses enjoyed riding and hunting, Mary with falcons, and they grew more in love as the years passed. Mary spent much of her time in the marriage in her husband’s Austrian lands, frequently governing them in his absences. A contemporary of Mary described her as “the queen of the romans is a prudent and wise woman, much endeavoured with virtue and charity towards the lowest of her subjects”. Her marriage to Maximilian had yielded four living children: Frederick of Austria b 1478, Eleanor of Austria b 1479, Charles of Austria b 1486 and Margaret of Austria b 1490.

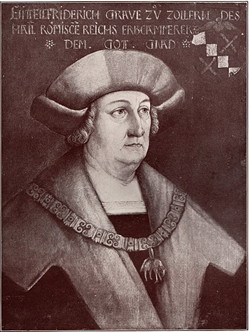

The leading man for the Hapsburg meeting was Eitel Friedrich II, Count of Hohenzollern, one of Maximilian’s most trusted men. He accompanied Maximilian to Aachen, being in charge of his entourage. Philip and Catherine arrived in Aachen in the first week of september, when the trees had just started to turn golden. For Catherine, the old city of Aachen was a beautiful sight, even if it’s charm were utterly different compared to Pamplona. The Duke and Duchess were greeted at Aachen by Johann Beissel, mayor of the city, who had offered the Aachen Town Hall as residence during their stay. Catherine, who was more exchausted than her husband by the journey (Philip being used to long travels) retreated with her ladies to her chambers, while her husband got the entourage and the packings settled in, afterwards spent the rest of the evening discussing matters of state with Johann.

The Hapsburg delegation arrived seven days later. The duke and duchess of Burgundy both witnessed Maximilian becoming elected as King of the Romans. The first point of the meeting was greetings and congratulations by both sides, Philip for his new marriage and Maximilian for his election. Philip gave gift for his brother-in law and baby Charles of Austria (having been born right before Maximilian left for Aachen. Philip and Catherine also became godparents for the little boy (Wolfgang Von Graben stood in for the Duke). Maximilian in turn gave Philip a bejewelled sword and a richly harnessed stallion as a wedding present.

Eitel Friedrich II, Count of Hohenzollern

Philip also got several letters from his sister Mary, one addressed to dowager duchess Margaret.

The meeting at Aachen went on for more than two weeks. The money and valuables given by Philip was counted and handed over to Eitel Friderich, as funds for the future election of Maximilian. Its total sum was unknown, but it’s believed that it was around 60 to 80,000 crowns. In return Philip got what he had longed for; The promise of a royal title. The Duke of Burgundy would become the King of Lotharingia, a lifelong dream for Charles the Bold.

More practical matters were also as hand. The renewal of the Burgundian-Hapsburg alliance and matters of trade between realms were discussed. But the core reason for the meeting had been finished and after the two weeks had passed, several days was spent hunting and jousting, to the delight of the people of Aachen. In the last days of September 1486, the ducal couple left Aachen to return to Namur in the low countries.

After a pleasant autumn journey, Philip and Catherine entered Namur in October, to a extreme cheer by the population. Catherine would stay until October in the city, Philip left for the Amsterdam in Holland a few days later, resuming his usual travels.

The Duke and duchess would not see each other again until shortly before Christmas, celebrated at the ducal palace of Malines.

Once Philip had returned to Namur, the dowager duchess Margaret arrived in the city. She would keep Catherine company during that autumn, introducing her to the cities in Brabant and Ghent with her. The company of Margaret was invaluable for Catherine, as she was still a stranger to many of her people. Perhaps Margaret remembered her own first year in Burgundy, being new to a large realm and a husband who spent much of his time on the roads? Margaret of York was also accompanied by her youngest daughter, Margaret, who adored Catherine and her fashionable clothing (no surprise as she was nine years old).

The count and countess of St Pol would arrive at Malines as well a week before Christmas, gathering the entire family at the palace. The Christmas was one of the happiest times the ducal family could remember in a long while. And Catherine of Navarre, found that she had gotten a home in her new land, and a husband she grew to love. The Christmas at Malines gave additional joy to the Duke and Duchess, a baby was announced after the new year celebrations in 1487.

On the 15th of June, at the palace of Ten Waele in Ghent, Catherine gave birth to a son, named Charles. The birth of an heir caused great joy in the cities and bonfires was lit in many places. The infant was christened with great splendour in the church of St Nicholas in the city seven days later. The baby was given the title of Count of Somme in lieu to replace the former titles of Count of Charolais as had formerly been given to the heir of the duchy. Margaret of York carried her grandson, wrapped in crimson cloth of gold trimmed with ermine. The corporation of Ghent presented a purse with 30, 000 crowns, Margaret gave the baby a gold lily, his uncle John a helmet and a sword.

Catherine’s churching six weeks later took place in St Michael’s Church. The church had been under it’s final reconstructions since 1440 and Duke Philip had provided a large fund for the buildings and had even commissioned altarpieces for the interior.

However, few families were spared the high child mortality at that time and three months after his birth, the little Count of Somme died in his cradle at Ten Waele on the 16th of September, much to his parent’s grief.

Charles would be buried in the church of St Michael, in a new chapel founded by his father. The distraught duke and duchess would spend the autumn and winter together in Malines, holding a subdued court.

Church of St Michael in Ghent, where Catherine was churched and Charles, Count of Somme were buried.

Catherine would have her second child in the 20th of June in Malines 1488. The baby was a girl, named Margaret, in honour of the Dowager Duchess. Her birth was greeted with happiness, despite her gender, and Philip and Catherine grew even closer. Philip is believed to have said “Now I have three Margarets to cherish in my court”. Her parents left Malines in September, continuing their travels once more. From Malines the voyage went to Breda, to Hauge in Holland, Middleburg and Bruges in November. The duke and duchess would spend much time together in their years of marriage, more than Charles and Margaret had. The closeness proved to be fruitful. Catherine gave birth to a second daughter in January 4th of 1490 in Cassel, called Magdalena, after her maternal grandmother. The duchess proved to be a popular lady with her subjects, and she acted both as her husband’s advisor and a representative to the cities. Catherine hosted many ambassadors to the low countries after 1487, performed charity on a large scale and kept herself well updated on every corner of the duchy. Aside from that she regularly visited her daughters, Margaret and Magdalena, both in the care of dowager duchess Margaret at the ducal palace in Malines. Both girls thrived under their grandmother’s attention. Catherine was as well determined to provide a brother for her little girls.

Catherine’s final pregnancy ended in summer of 1491. The joy of the birth of a healthy and strong son, Philip in 19th July, in Bruges, was followed by enormous sorrow as the Duchess herself perished five days later from a ruptured placenta after the agonising birth.

Duke Philip took his beloved wife’s death hard. The happiness during the five years of marriage had been genuine and solid, the sudden loss of Catherine tore everything asunder like tissue paper. Philip withdraw from the court for a whole month, staying in his apartment, refusing to meet all but a few visitors. For the ever active Duke, who had since 1486 keep a close hands of state affairs, the isolation was telling. John, Count of St Pol, took up the reins in his brother’s absence and the funeral of Catherine was arranged by countess Marie and dowager duchess Margaret.

The late duchess was buried in the Church of Our Lady, in the same chapel as Charles the Bold lay.

Tomb of Catherine of Navarre, duchess of Burgundy

The funeral ceremony for Catherine was elaborate, long winding processions in black clothing processed through the street, the city draped in black cloth, mourners tossing flowers at the carriage. In 1502, Pierre de Beckere of Brussels created a magnificent bronze monument for the tomb.

The death of the duchess led to the Estates assembling in Ypres at late September. The birth of Philip, count of Somme, had secured the ducal sucession somewhat, but as seen with the late baby Charles four years earlier, misfortune could strike at any time.

Duke Philip had to remarry and preferably soon. The Estates did grant the duke’s wish for a year of mourning and six months later, as respect to the late duchess’s memory, the search begain anew for the next duchess.

@kasumigenx ask and ye shall recive!

While Charles VIII was not happy over the outcome, Philip of Burgundy certainly was. The hard years of 1477-80 had been repaid in kind. The duke could concentrate on consolidate his various realms without worrying about French meddling. The regency had ended on his seventeenth birthday in 1486 and the duke could exercise his power properly. His house was in order, his brother John had turned eleven years old, showing himself to be an athletic and promising youngster, little Margaret, now nine, a charming girl. His sister-in law Marie blossomed into a bright young lady, enjoying the company of the dowager duchess. Now it was time for Philip to get a proper duchess of his own and in spring of 1486, Catherine of Navarre left Pamplona, biding farwell to her brother and mother, Magdalena of France for the last time.

The King of Navarre, Francis Phoebus, had been betrothed to the second daughter of Isabella and Ferdinand, infanta Ana of Castile. However, the arrangements for the match would drag along for many years, as either side had different terms for the match. The king’s marriage in 1491, however, would blindside pretty much everyone and become the final nail in the coffin of Navarre’s independence.

-Source: Phoebus the Dim – The last king of Navarre, Margaret Elijah Watson.

Catherine of Navarre arrived in Amiens in July 1486. Her travel had taken her trough France, from Bordeaux, Poitiers, Orléans and into Paris. Catherine and her entourage stopped to rest for over a week and to bring the greetings of Navarre for the new king. The promised dowry from France was also entrusted to her, being a big sum of 170, 000 crowns. Catherine also meet her sister-in law Isabella and Anne of France. All three ladies spend a pleasant time together, seeming to get well along. After Paris, the Navarre company left for Amiens.

Catherine arrived in late evening in Amiens on 4th July. She was received by the burghers of the city and Philippe Crevecoeur, the ducal governor of Picardy. Similar to her mother-in law’s arrival in 1468, the citizen of Amiens stood outside their houses holding lit torches. The burgers gifted Catherine with a purse of 15 marks and Philippe presented a her with a ruby and emerald brooch from Duke Philip, who had just left Arras the same evening. Catherine and her people were given the townhouse of the bishop of Arras, Jean Jouffroy, to rest after the journey. The next evening, she got two visitors, the dowager duchess Margaret and countess Marie. Their first meeting, as court etiquette demanded, included kneeling in silence in solemn respect. Afterwards the ladies dined in private. Margaret seemed very pleased with Catherine, both her manners and charm.

At the time of her marriage the eighteen-year-old Catherine was a charming young woman, being around 5,7 feet tall with golden brown hair and grey-brown eyes. She had a creamy complexion and thin arched brows with a straight nose.

Catherine of Navarre, duchess of Burgundy, made in 1488

Two days later Philip arrived in Amiens. Catherine was acclaimed the duchess of Burgundy by the bishops of Arras and the members of the Estates who had arrived with the Duke. The marriage was celebrated the day afterwards, the ceremony taking place in the Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Amiens (Notre-Dame d’Amiens) Compared to the private wedding of Charles the Bold and Margaret of York, this was a full blow spectacle. As the previous one had been Charles’s third marriage it was understandably.

Notre-Dame d’Amiens

The city set was set to greet its new duchess with the same glorious splendour as her mother-in law had gotten years earlier. The spectacles of biblical stories, the music from the best Flemish composers, the fireworks in the night sky and tournament between the greatest (and most glittering) knights of the duchy; all in total to showcase the splendour of the duchy to the world. Bishops and churchmen leading great processions at evening, holding candles and swinging thuribles waving burning incense. Richly dressed merchants from every kingdom in Europe had gathered in the city, showing off their wealth and of the duke.

A fashionable lady, Catherine arrived at the cathedral on horseback (a beautiful white mare given by Philip) clad in a richly decorated gown of cloth of gold, and a short-sleeved overrobe of blue velvet embroidered with gold. Her hair was loose and a small net with pearls was attached. The charming duchess had a joyful demeanour, a fresh breath of air after troublesome years. The marriage had gotten off to a great start and the ten whole days was spent in celebration and festivities by all in Amiens; the new duchess had been received with love by her husband and her new subjects.

After the wedding feasts the everyday work of the low countries began anew. Most members of Catherine’s entourage left, a handful remained, her six ladies among others. Philip left Amiens to travel to Aachen, both for religious reasons and business. Catherine chose to accompany her husband. The point of the trip to Aachen was to meet up with Maximilian of Austria, who was to be elected king of the romans in the cathedral. Philip had ambitions for his duchy and Maximilian was in need (as he often was) of money. Margaret of York were as usual left to manage the duchy in his absence.

One notable item Philip took with him to Aachen was a coronet owned by his mother Margaret. It had been given by Charles the Bold at the wedding, the coronet itself trimmed with pearls, precious stones and enamelled white roses. The presentation of the dowager’s crown to one of the oldest cathedrals in Europe, constructed by Charlemagne, by the king of Romans’ brother-in law carried strong implications. Aachen was the traditional crowning place of the Holy Roman Emperors and the old emperor, Frederick III, was ailing. The ascension of Maximilian became imminent, as the king of the romans was the title of the imperial successor.

Crown of Margaret of York, Aachen Cathedral

The main reason for the meeting between Philip and the Maximilian was to secure the future election of Maximilian as Holy Roman Emperor. Philip brought a considerable amount of money and valuables with him to Aachen for that purpose.

The marriage of Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy had since leaving Burgundy in 1478 flourished. Both spouses enjoyed riding and hunting, Mary with falcons, and they grew more in love as the years passed. Mary spent much of her time in the marriage in her husband’s Austrian lands, frequently governing them in his absences. A contemporary of Mary described her as “the queen of the romans is a prudent and wise woman, much endeavoured with virtue and charity towards the lowest of her subjects”. Her marriage to Maximilian had yielded four living children: Frederick of Austria b 1478, Eleanor of Austria b 1479, Charles of Austria b 1486 and Margaret of Austria b 1490.

The leading man for the Hapsburg meeting was Eitel Friedrich II, Count of Hohenzollern, one of Maximilian’s most trusted men. He accompanied Maximilian to Aachen, being in charge of his entourage. Philip and Catherine arrived in Aachen in the first week of september, when the trees had just started to turn golden. For Catherine, the old city of Aachen was a beautiful sight, even if it’s charm were utterly different compared to Pamplona. The Duke and Duchess were greeted at Aachen by Johann Beissel, mayor of the city, who had offered the Aachen Town Hall as residence during their stay. Catherine, who was more exchausted than her husband by the journey (Philip being used to long travels) retreated with her ladies to her chambers, while her husband got the entourage and the packings settled in, afterwards spent the rest of the evening discussing matters of state with Johann.

The Hapsburg delegation arrived seven days later. The duke and duchess of Burgundy both witnessed Maximilian becoming elected as King of the Romans. The first point of the meeting was greetings and congratulations by both sides, Philip for his new marriage and Maximilian for his election. Philip gave gift for his brother-in law and baby Charles of Austria (having been born right before Maximilian left for Aachen. Philip and Catherine also became godparents for the little boy (Wolfgang Von Graben stood in for the Duke). Maximilian in turn gave Philip a bejewelled sword and a richly harnessed stallion as a wedding present.

Eitel Friedrich II, Count of Hohenzollern

Philip also got several letters from his sister Mary, one addressed to dowager duchess Margaret.

The meeting at Aachen went on for more than two weeks. The money and valuables given by Philip was counted and handed over to Eitel Friderich, as funds for the future election of Maximilian. Its total sum was unknown, but it’s believed that it was around 60 to 80,000 crowns. In return Philip got what he had longed for; The promise of a royal title. The Duke of Burgundy would become the King of Lotharingia, a lifelong dream for Charles the Bold.

More practical matters were also as hand. The renewal of the Burgundian-Hapsburg alliance and matters of trade between realms were discussed. But the core reason for the meeting had been finished and after the two weeks had passed, several days was spent hunting and jousting, to the delight of the people of Aachen. In the last days of September 1486, the ducal couple left Aachen to return to Namur in the low countries.

After a pleasant autumn journey, Philip and Catherine entered Namur in October, to a extreme cheer by the population. Catherine would stay until October in the city, Philip left for the Amsterdam in Holland a few days later, resuming his usual travels.

The Duke and duchess would not see each other again until shortly before Christmas, celebrated at the ducal palace of Malines.

Once Philip had returned to Namur, the dowager duchess Margaret arrived in the city. She would keep Catherine company during that autumn, introducing her to the cities in Brabant and Ghent with her. The company of Margaret was invaluable for Catherine, as she was still a stranger to many of her people. Perhaps Margaret remembered her own first year in Burgundy, being new to a large realm and a husband who spent much of his time on the roads? Margaret of York was also accompanied by her youngest daughter, Margaret, who adored Catherine and her fashionable clothing (no surprise as she was nine years old).

The count and countess of St Pol would arrive at Malines as well a week before Christmas, gathering the entire family at the palace. The Christmas was one of the happiest times the ducal family could remember in a long while. And Catherine of Navarre, found that she had gotten a home in her new land, and a husband she grew to love. The Christmas at Malines gave additional joy to the Duke and Duchess, a baby was announced after the new year celebrations in 1487.

On the 15th of June, at the palace of Ten Waele in Ghent, Catherine gave birth to a son, named Charles. The birth of an heir caused great joy in the cities and bonfires was lit in many places. The infant was christened with great splendour in the church of St Nicholas in the city seven days later. The baby was given the title of Count of Somme in lieu to replace the former titles of Count of Charolais as had formerly been given to the heir of the duchy. Margaret of York carried her grandson, wrapped in crimson cloth of gold trimmed with ermine. The corporation of Ghent presented a purse with 30, 000 crowns, Margaret gave the baby a gold lily, his uncle John a helmet and a sword.

Catherine’s churching six weeks later took place in St Michael’s Church. The church had been under it’s final reconstructions since 1440 and Duke Philip had provided a large fund for the buildings and had even commissioned altarpieces for the interior.

However, few families were spared the high child mortality at that time and three months after his birth, the little Count of Somme died in his cradle at Ten Waele on the 16th of September, much to his parent’s grief.

Charles would be buried in the church of St Michael, in a new chapel founded by his father. The distraught duke and duchess would spend the autumn and winter together in Malines, holding a subdued court.

Church of St Michael in Ghent, where Catherine was churched and Charles, Count of Somme were buried.

Catherine would have her second child in the 20th of June in Malines 1488. The baby was a girl, named Margaret, in honour of the Dowager Duchess. Her birth was greeted with happiness, despite her gender, and Philip and Catherine grew even closer. Philip is believed to have said “Now I have three Margarets to cherish in my court”. Her parents left Malines in September, continuing their travels once more. From Malines the voyage went to Breda, to Hauge in Holland, Middleburg and Bruges in November. The duke and duchess would spend much time together in their years of marriage, more than Charles and Margaret had. The closeness proved to be fruitful. Catherine gave birth to a second daughter in January 4th of 1490 in Cassel, called Magdalena, after her maternal grandmother. The duchess proved to be a popular lady with her subjects, and she acted both as her husband’s advisor and a representative to the cities. Catherine hosted many ambassadors to the low countries after 1487, performed charity on a large scale and kept herself well updated on every corner of the duchy. Aside from that she regularly visited her daughters, Margaret and Magdalena, both in the care of dowager duchess Margaret at the ducal palace in Malines. Both girls thrived under their grandmother’s attention. Catherine was as well determined to provide a brother for her little girls.

Catherine’s final pregnancy ended in summer of 1491. The joy of the birth of a healthy and strong son, Philip in 19th July, in Bruges, was followed by enormous sorrow as the Duchess herself perished five days later from a ruptured placenta after the agonising birth.

Duke Philip took his beloved wife’s death hard. The happiness during the five years of marriage had been genuine and solid, the sudden loss of Catherine tore everything asunder like tissue paper. Philip withdraw from the court for a whole month, staying in his apartment, refusing to meet all but a few visitors. For the ever active Duke, who had since 1486 keep a close hands of state affairs, the isolation was telling. John, Count of St Pol, took up the reins in his brother’s absence and the funeral of Catherine was arranged by countess Marie and dowager duchess Margaret.

The late duchess was buried in the Church of Our Lady, in the same chapel as Charles the Bold lay.

Tomb of Catherine of Navarre, duchess of Burgundy

The funeral ceremony for Catherine was elaborate, long winding processions in black clothing processed through the street, the city draped in black cloth, mourners tossing flowers at the carriage. In 1502, Pierre de Beckere of Brussels created a magnificent bronze monument for the tomb.

The death of the duchess led to the Estates assembling in Ypres at late September. The birth of Philip, count of Somme, had secured the ducal sucession somewhat, but as seen with the late baby Charles four years earlier, misfortune could strike at any time.

Duke Philip had to remarry and preferably soon. The Estates did grant the duke’s wish for a year of mourning and six months later, as respect to the late duchess’s memory, the search begain anew for the next duchess.

@kasumigenx ask and ye shall recive!

Last edited:

Well, Philip does not have it yet, but it might come one day. Catherine of Navarre did kind of loose however.

Threadmarks

View all 57 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 47 - Edmund the Grouch-back Chapter 48 - Keeping up with the Stewarts Chapter 49 - I'm rather lost at the moment Chapter 50 - We resume events in Burgundy in 1517 Chapter 51 - The Grand Duchy of Brabant - 1505- 1512 Author's update. Regarding the ethics of rewriting chapters Edits update regarding rewamping Final chapter update

Share: