You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Marriage of the Century - A Burgundian Timeline

- Thread starter BlueFlowwer

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 57 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 47 - Edmund the Grouch-back Chapter 48 - Keeping up with the Stewarts Chapter 49 - I'm rather lost at the moment Chapter 50 - We resume events in Burgundy in 1517 Chapter 51 - The Grand Duchy of Brabant - 1505- 1512 Author's update. Regarding the ethics of rewriting chapters Edits update regarding rewamping Final chapter updateI think it is possible for Poland to have the complete Suzerainty of the Ethnic Polish duchies in Silesia in exchange for recognizing Habsburg rule in Bohemia, from partial earlier into complete suzerainty.Well, if Vladislaus still had no son or child Max has good chances to being able to take at least Bohemia...

Plus here instead of the troubles with Burgundy he will have a lot of money as dowry for Mary and will be able to use them for reinforce his rule over Austria (and if Mary died around 1490 he can always remarry to Bianca Maria Sforza and receive also her dowry)

Last edited:

Chapter 8. Her hands on the reins.

Chapter 8. Her hands on the reins.

The years of 1477-81 would be hard for Burgundy. Foreign enemies posed a danger, as well as internal ones. Charles of Burgundy had not been a gentle ruler to his people and with this tyrant gone, the Burgundian subjects began to erupt in frustration and rage. Three ducal armies had been destroyed since 1475 and the harsh taxation, the abuse of ducal officials and the suppression of regional rights added righteous fury to the people’s fire.

Margaret of York’s first action after hearing about the disaster of Nancy was to put the castle of Ten Waele under heavy guard. Mary and her young children’s survival were to be safeguarded. With Philip, now duke in his own right, soon to be eight years old, a regency was necessary until he came of age. Isabella and John, her other children, needed to survive as well. All three were placed under an armed household, in the youngest twos case, a nursery. Philip already had a minor household himself.

The dowager duchess second act was to send for the Estates General to converge in Ghent as soon as possible. An army of messengers were dispatched all over the duchy; promising lesser taxations, a more open government and a gentler hand in ruling.

Despite the strife that opened after Nancy, some checks and balances remained to prevent total chaos. Charles the Bold had two thriving sons, even if they were young. The danger of Mary’s future husband becoming the ruler of Burgundy was gone. Margaret herself proved a force in her own right, the cities and councils were well acquainted with their duchess and she had proven herself more trustworthy and open than her husband. Her actions, already starting the week after Charles’s death also went a long way to assure many.

The Great Privilege, drafted a week after the news of Nancy broke, was a political move that settled the biggest issues. When the Estates General assembled later in January at Ghent the charter presented several things: The reminder of the 500, 000 crowns that Charles had been promised was renounced, the Estates would be allowed to gather at any location, the regional courts rights were strengthened to prevent the central court at Malines (much hated by the people), and a Grand council made up by delegates by the Estates would make up the regency with the duchess. Margaret however demanded custody of her children, both her sons and Isabella.

Margaret had several supporters that rallied around her. Anthony, Count of La Roche, Charles’s bastard brother, Philippe de Crévecoeur, the ducal governor of Picardy and Charles Biche, the late Duke’s chamberlain stayed and threw their support for her. Other ducal administrators consisted of Chancellor Hugonet, Lord Humbercourt and Lord Ravenstein. These three men were not popular, particularly the first two. The people hated Humbercourt for his cruelty and oppression of cities and Hugonet had been chief enforcer of Charles’s harsh taxation. Another ducal official in Ghent became the target of the people’s rage: Jan Van Melle, a corrupt tax collector who had enriched himself.

However, the biggest danger to Burgundy was France. Louis XI had immediately sprung into action after hearing about Nancy. French forces invaded the county of Burgundy, the palatinate of Burgundy, Macon and Charolais. All these places were far away from Ghent. The duchess was unable to aid with all her effort focusing on keeping the Flemish from erupting. While Louis could not claim all of Burgundy’s fief as Philip of Burgundy and little John prevented the claim that the Burgundian lands were forfeit to the French crown, he had no intentions of doing nothing. Louis focused on these regions, as well as supporting René of Lorraine, for his claim to Lorraine and Bar. In February the regions were overrun with French forces, and Margaret was unable to help them. Some French forces attacked Hainault and Luxemburg as well.

Burgundy at the time of Charles the Bold's death.

Margaret did gain a certain goodwill with the Estates from the Great Privilege and the french invasions did rally a larger amount of the Burgundian people to a unity. The burning of their villages did surprisingly not endear the victims to Louis forces and the loss of farms and supplies in winter made the delegates of Hainault and Luxemburg, especially, to fiercely support their dowager duchess.

Margaret also reached out to various allies; ambassadors were dispatched to England, to Emperor Frederick III and even to Portugal, at the court of king Alfonso VI. The Portuguese crown prince John got a second son with his wife Eleanor of Viseu in April 14th 1477, a infante named Peter, named for the late duke of Coimbra, during the war with Castile and Aragon.

The marriage of Maximilian of Austria and Mary of Burgundy would be an alliance against France. Margaret also offered her daughter’s hand to the Prince of Wales, in exchange for an army to protect Burgundy. Louis did send a delegation to the dowager as well, with a proposal of marriage between Isabella of Burgundy and Charles, dauphin of France. In return Louis offered his niece Catherine of Navarre’s hand to Philip of Burgundy. Margaret turned that down, hoping for her brother’s support against France.

Catherine of Navarre

The turbulence in Ghent continued well until March. The Great Privilege had been accepted by the Estates, but the anger towards certain ducal officials did not subside. Margaret might be held in higher esteem and no one was willing to attack the pregnant dowager duchess, but the same could not be said for others. Humbercourt, Hugonet and Jan Van Melle, as well as Guillaume de Clugny, the papal Pronotary soon found themselves as targets. All four men were arrested early in March and Melle’s house plundered by its wealth. Despite Margaret’s attempts of creating a proper trial, the men were sentenced to death and beheaded in public in late March.

The bloodletting seemed to have calmed down the Flemish people, as their most hated officials had faced justice. In April, a week after his eight birthday, Philip of Burgundy was sworn in as Duke of Flanders at the St Nicholas Church. The public appearance of the young duke and the pregnant Margaret seemed to win a lot of the Flemish over, especially Philip who displayed a maturity and dignity far above his years.

One other notable ally of Margaret would be Jehan van Dadizele. Jehan was the lieutenant general of Flanders and an important member of the Flemish nobility. He had been one of the negotiators when the Estates received the Great Privilege and defended the Flemish rights. A trusted and able man of Flanders, he requested a meeting with the dowager duchess, the great council and duke Philip. The meeting took place in mid-April and he offered the ducal family his council in exchange for the rights of Flanders to be upheld.

Margaret accepted him as advisor and Jehan gave the young Philip his pledge, in return Philip swore to upheld the rights as his liege lord. Jehan would be a prominent member of Philip’s regency, keeping order in Flanders, much to public relief.

Note: Jehan was otl murdered in 1481, probably on the orders of archduke Maximilian, who tried to circumvent the Flemish rights, something that backfired on him. Here he survives and becomes a councillor to Philip and Margaret, so the Flemish situation is much better.

In April 1477 Maximilian began the slow journey towards the Low Countries. Margaret and the emperor had managed to settle the marriage arrangement between him and Mary. Despite Mary no longer being the heiress of the Low Countries, she was still a desirable bride. And a rich one, Margaret had promised a dowry of 150, 000 crowns as well gold plate, jewellery and other valuable possessions. In return the Hapsburg would provide military resources to Burgundy’s defence. The prestige of Mary’s imperial marriage was important.

The Estates General had been hard pressed by the delegates of Hainault, among others, to raise a force strong enough to repel the French invaders in february. The estates agreed to raise a force of 50,000 men, around 13,000 had been levied in March. The new force attacked the French at Hainault and after spring, the area had been freed of invaders. Louis XI directed the remaining men to move back to Luxemburg. However, the French army had not been freed of trouble either. Dysentery had spread among the men and even in France, there were increased voices that his attack on Burgundy was unfunded. He had no rights to any fief belonging to the late Duke since Charles the Bold had male heirs at his death. One prominent action was Pope Sixtus IV sending an embassy to Paris to protest his invasion. The threat of excommunication was included. In result Louis had to withdraw from Luxemburg in summer of 1477. Despite that the military continued in the county of Burgundy, Charolais and Macon for a long while.

Margaret was able to depart Ghent in late May. She moved to her dower town of Binche in Hainault, despite being six months pregnant. Her three children came with her on the journey while Mary remained in Ghent.

In Binche Margaret accomplished several goals; she met with the Hainault council as well as the leading officials in her dower town and Philip was sworn in as Count of Hainault in the neighbouring city of Mons in mid-June. The presence of the young duke and their beloved dowager provided a huge rally and the province of Hainault finally kicked the French out in July. When she arrived in Binche Margaret had also organised an impressive and solemn service in the late duke’s memory. The ceremony took place at night with a long procession of torchbearers winding through the city, who had been clad in black velvet.

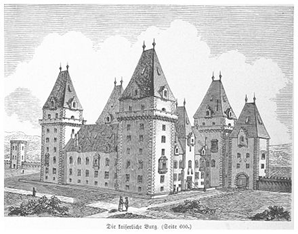

The Town Hall where Philip was sworn in as Count of Hainault

The dowager had paid for twenty pauper’s mourning clothes who took part in the ceremony. She and the children travelled with the train, little John carried by a nurse, Philip on horseback. Margaret and Isabella sat in an open carriage, both in black fur-lined gowns.

However, in the early days of July Margaret could no longer be as active as she used to be. She stayed in Mons and on the 5th of July she gave birth to her late husband’s final child: A daughter named Margaret.

By July Margaret was able to receive the French army at Hainaults surrender. Several captains had been taken prisoners by the Burgundians and weapons and pieces of artillery fell into their hands as well. In exchange for his war captains, Louis freed the Count of Chimay and Olivier de La Marche who had been taken ransom after Nancy. La Marche was a important courtier and he would remain one of the dowager’s most trusted men.

Margaret stayed at Mons with her children and baby Margaret until late September when she and her family moved to Malines (modern day Mechelen). The four ducal children needed a safe home for the foreseeable future, particularly John and the girls. Malines was a excellent choice for residence. Brabant was a more loyal region to the ducal rulers, rather than Flanders and Malines itself was centrally placed among Margaret’s dower towns. The city was guarded by walls and moats, making it easily defended. It had a reputation for being clean and livestock was not allowed to wander free. The ports were busy with traffic and the large population could sustain the industrial and commercial prosperity. Lacemaking provided work for the women of the city, as well as carpet weaving. Manufacturers of glass, pottery and leatherworks domineered the industry. Malines also had a reputation for metal crafts and armouries and bellmakers.

It was a ideal place for a ducal residence, but one problem remained. Malines did not have a ducal palace. Margaret solved that by purchasing the property of the bishop of Tournai. She also brought the seven adjourning houses and their land. The city of Malines welcomed their ducal family and she received around 3, 000 florins to bear up the expenses. Isabella, John and baby Margaret finally had a proper home. Philip would not stay in Malines at much as his siblings, until 1485 he travelled with his mother.

Mary of Burgundy and Maximilian of Austria

Margaret left her three youngest children in Malines and returned to Ghent in October. She and Philip had to attend the marriage of Archduke Maximilian and Mary. The young Austrian man had arrived in Ghent at late September. His journey had been very slow, most likely to levy the men and weapons that had been the terms for his marriage. Mary had remained in Ghent and had meet with the estates to aid in any further trouble. She had also gathered her dowry for the marriage. Around 40,000 crowns, almost half one third of the promised 150,000 had been collected when her groom arrived. To add to that, many gold and silver plates, jewellery and valuable tapestries were also included.

Maximilian entered Ghent escorted by 700 horsemen and around 11, 000 men. The army itself was Maximillian’s gift to Burgundy and one of the terms for the wedding. The duchess and young Philip received the army when they arrived in October.

The arrival of a imperial army both gladdened and worried the Flemish cities. They did not want further war with France and was weary of Hapsburg politics in the duchy. However, a army, that they did not have to be even more taxed for, would help. Maximilian’s charming manner did cause some suspicions about him trying to influence Philip.

Furthermore, his annunciation that he would stay until spring in Flanders did not sit well with the people. The archduke would try to rule Burgundy with german and Austrian interests, it was said among the street. Duke Philip was still very young. Mary and Maximilian married in St Bavo’s Cathedral in October. The logistics of the travel back home to Vienna demanded a longer stay, but Maximilian did not stay until spring. He would find his attempts to insert himself in the council, or in Philip’s circle hard to do and Mary had successfully gathered further 30, 000 crowns by new year of 1477. The archduke and his bride left Ghent in the second week of January, to reach Vienna and the Austrian heartlands in mid-May.

In Vienna Mary’s first child was born on the 3th of September. A son named Charles. The remainder of the dowry would be paid over the course of the next two years. Her second child, named Eleanor for Maximilian’s mother, was born in 1479, on November 10th.

Hofburg Castle in Vienna. This remained the seat of the Hapsburgs and Charles of Austria was born here in September 1478.

"Margaret and Mary would never see each other again, but they would keep in close contacts through diplomats and letters. Margaret’s education of Mary and her firm hand in crisis set a example for her step-daughter that would remain prominent for the remainder of her life"

-Source: Empress Mary of Burgundy, Stephan Kolner.

With her stepdaughter having left for Austria, Margaret and Philip would remain in Flanders until spring. They left for Hesdins in March to be closer to the Somme. The imperial marriage had enraged Louis XI of France and after Christmas he targeted the Somme towns, a region that had long been twisted by the dukes of Burgundy and France. At Hesdins, Margaret sent a delegation to London to try to get her brother, Edward IV of England to act. She also took around 5,000 men to repel the French invaders. The delegates of Picardy and Artois also backed their duke and around 2, 500 additional men joined the fighting.

The ducal embassy to England met with difficulties in their negotiations. Margaret had offered her son Philip’s hand to Mary of York, Edward’s second daughter. The old idea of a marriage between Isabella of Burgundy and Edward, prince of Wales also resurged. Edward was enthusiastic about a double marriage between England and Burgundy, but his sister was hesitant. To make things even worse, Edward seemed to have little to no intention of paying a dowry for Mary. He was still very attached to his French pension from the Treaty of Picquigny. In exchange for Mary he offered a invasion of France in return for a Burgundian pensions, something that Margaret doubted would occur.

Edward, Prince of Wales.

Finally, after two months of negotiations, an agreement was made. Isabella of Burgundy was betrothed to her cousin, the Prince of Wales. The marriage would take place at her 15th birthday in 1486. She would bring a dowry of 120, 000 crowns and in return the Burgundians could raise 10, 000 archers from England.

Margaret was able to gather 3, 000 ones before summer and they joined forces with the men at Somme. By autumn the French had been repelled from Somme, much to people’s relief.

After the victory Philip was sworn in as Count as Artois and Picardy at St Omer. The nine year old Duke had by now learned his first practical lessons in governance and military tactics.

Philip of Burgundy in 1478. One of the few portraits that had survived of his childhood

The young duke is seen wearing the Order of the Golden Fleece around his neck, a order started by his grandfather Philip the Good in 1430. Unknown artist.

The losses in the Somme had taught Louis XI a lesson; The county of Burgundy would become his sole prize. He focused his effort once more on that region and Charolais and Macon as well. The duchy of Lorraine had become Duke René’s once more, so any Burgundian influence was permanently lost there.

Louis efforts of winning over the estates of Burgundy was in full swing by 1479. He offered generous conditions towards the councils. Lenient taxations, a less corrupt government and privileges to the merchant community. Already in Charles the Bold’s time there had been a drift in that region towards France, so the plan had a good chance of succeeding. Despite that there was still a large community staying loyal to the ducal rulers and they protested heavily against the invasions. The Estates General were not able to defend the county efficiently, due to Lorraine blocking the way for reinforcements. Louis also sent emissaries to the Grand Council, once again bringing up a match between Isabella of Burgundy and Charles, the dauphin as a peace treaty.

The council had mixed receptions to that treaty. On one hand it would resolve the problems with France, but on the other, the county of Burgundy belonged rightfully to Duke Philip. The terms were also more favourable to France, being just losses for the duchy. The dauphin was also still betrothed to Elizabeth of York, the oldest daughter of Edward IV. And Isabella of Burgundy was the future princess of Wales.

The Flemish cities reacted positively to the French proposal. To sweeten the deal with Burgundy further, Louis offered his niece Catherine of Navarre to Duke Philip, even promising an impressive dowry for her. Margaret however was not convinced and refused the offer. In the summer of 1479 negotiations had reached a standstill. Louis decided to press the dowager further, sending two letters bearing his terms for a treaty. One was for Margaret and the other was to the Estates in Flanders.

Louis terms for peace contained the following:

Isabella of Burgundy would be betrothed to the Dauphin, and be raised in France until the wedding (Louis wanted the marriage to take place when she turned 13).

Her dowry would be the County of Burgundy, The Palatine of Burgundy, Charolais and Macon.

Philip would be betrothed to Catherine of Navarre, Louis’s niece. The king of France would provide a good dowry for her.

Margaret’s full dower lands would be restored to her.

Louis renounced all French claims to the other Burgundian fiefs, acknowledging Philip’s inheritance.

Margaret initially turned the treaty down, not wanting to give her daughter to the French. She was determined to regain the Burgundy regions. Unfortunately, this time the dowager played straight into Louis hands.

After hearing her rejection, Louis send a delegation to Ghent, demanding to know why the dowager duchess was not open to negotiations. Perhaps the letter sent to her had been lost? The estates in Flanders sent representatives to Margaret to get to the mystery. Under pressure the dowager was forced to show that she had received the letter from Louis, causing the Flemish cities to erupt in anger. Now it looked like Margaret had been dishonest with the Estates, not wanting to negotiate out of stubborn pride.

This caused a uproar against the dowager and the Grand Council. Calls to end the war was shouted in the streets of Ghent and Brussels. The Flemish called for the custody of Philip to be removed from the dowager as well. Facing enormous pressure by the people, Margaret and the Grand Council were forced into open negotiations with the King of France.

In October the Treaty of Arras was struck between Burgundy and France. Louis terms was agreed upon, with a few small changes, the marriage would take place at Isabella’s 15th birthday, not the 13th. Isabella would also keep a few Burgundians in her household, among those a couple of ladies chosen by her mother. The future dauphine would leave for France in 1480, not at once as Louis had desired. However, those changes were not of great importance to him. He succeeded in his goals at last.

Once the treaty of Arras had been made by both parties, the anger towards the dowager lessened. Jehan van Dadizele, the lieutenant General of Flanders had been once of the chief negotatiors with France and he reassured the the Flemish people that the dowager would keep her word. Duke Philip would stay with his mother.

Isabella of Burgundy in 1481, the painting was made by Jean Hey. A miniature portrait was sent to her mother Margaret the same year.

Margaret spent Christmas and the early spring with her daughters’ constant company. Preparations for her journey to France included an updated trousseau with clothing, gold and silver plates, tapestries and other possessions. Records for the dowager’s expenses shows cloth of gold and silver being ordered, fine Rennes linen, scarlet, purple and green velvets and blue and pink silks, along with the payments for tailors and shoemakers.

As a bibliophile Margaret also ensured that her daughter would leave with plenty of literature of different genres. The introduction of the printing press earlier would ensure that Margaret lived in a court of living authors. A few of the books given to Isabella came from her mother.

-Les Chroniques de Flandre, a book about the history of Flanders. Perhaps a reminder to her daughter of her heritage.

-La Somme le Roi, a sermon from a famous theologian Father Laurent du Bois, popular at court.

-Vie de St Colette, a religious work about St Colette.

-Recueil des Histories de Troie, (Collection of the stories of Troy), a copy of the book Margaret had gotten by William Caxton, who had introduced the printing press in England. Margaret had been his patron.

-Le Livre de la Cité des Dames, (The book of the city of ladies), the classic work of Christine de Pizan.

Margaret also employed a jewelsmith to make a collection of jewelry for her daughter. Necklaces of gold with rubies and diamond rings, as well as collar of white roses with pearls was included in her belongings.

Isabella showed a tendency of clinginess to her mother and oldest brother during these preparations, perhaps anxiety for the separation. Leaving her little siblings, John and Margaret was especially hard. Isabella had doted on them ever since they were born and in the nursery of Malines. The reputation of Louis XI as a father in law seemed to scare her. To Isabella, growing up with her duchy nearly constantly at war with France, the king had taken the form of a giant spider or a demon with horns and three eyes. Her inquiries about the dauphin got better results. Charles was described as a intelligent boy with charm.

Charles VIII of France

It was said that the miniature picture of Isabella that Charles received left the prince with positive feelings towards his fiancé.

In late March Isabella left with her mother and the entourage towards France. She was accompanied to Reims, where the royal delegates meet them at the cathedral. John II, duke of Bourbon, Anne of France, the eldest daughter of Louis XI and the bishop of Reims. Her arrival was celebrated as a alliance of peace by the French people. Isabella was handed over before the cathedral and publicly acclaimed as the Dauphine of France. The betrothal was blessed by the bishop of Reims inside the cathedral.

Isabella and Margaret spent three days together in Reims, to make sure that all the belongings got transferred and to let the Burgundians rest before the journey home. Margaret learned too her relief that Isabella’s education as dauphine would be handled by Anne of France, a capable and tall woman, who seemed kind to the little princess. After the three days the dowager duchess returned to Burgundy with her people.

Unlike with her stepdaughter, Margaret would see her daughter again and she would receive letters from Anne of France and Isabella. But nevertheless, the loss of her oldest girl would sting for a long while.

Anne of France, duchess of Bourbon. Louis daughter and the caretaker to Isabella of Burgundy.

The years of 1477-81 would be hard for Burgundy. Foreign enemies posed a danger, as well as internal ones. Charles of Burgundy had not been a gentle ruler to his people and with this tyrant gone, the Burgundian subjects began to erupt in frustration and rage. Three ducal armies had been destroyed since 1475 and the harsh taxation, the abuse of ducal officials and the suppression of regional rights added righteous fury to the people’s fire.

Margaret of York’s first action after hearing about the disaster of Nancy was to put the castle of Ten Waele under heavy guard. Mary and her young children’s survival were to be safeguarded. With Philip, now duke in his own right, soon to be eight years old, a regency was necessary until he came of age. Isabella and John, her other children, needed to survive as well. All three were placed under an armed household, in the youngest twos case, a nursery. Philip already had a minor household himself.

The dowager duchess second act was to send for the Estates General to converge in Ghent as soon as possible. An army of messengers were dispatched all over the duchy; promising lesser taxations, a more open government and a gentler hand in ruling.

Despite the strife that opened after Nancy, some checks and balances remained to prevent total chaos. Charles the Bold had two thriving sons, even if they were young. The danger of Mary’s future husband becoming the ruler of Burgundy was gone. Margaret herself proved a force in her own right, the cities and councils were well acquainted with their duchess and she had proven herself more trustworthy and open than her husband. Her actions, already starting the week after Charles’s death also went a long way to assure many.

The Great Privilege, drafted a week after the news of Nancy broke, was a political move that settled the biggest issues. When the Estates General assembled later in January at Ghent the charter presented several things: The reminder of the 500, 000 crowns that Charles had been promised was renounced, the Estates would be allowed to gather at any location, the regional courts rights were strengthened to prevent the central court at Malines (much hated by the people), and a Grand council made up by delegates by the Estates would make up the regency with the duchess. Margaret however demanded custody of her children, both her sons and Isabella.

Margaret had several supporters that rallied around her. Anthony, Count of La Roche, Charles’s bastard brother, Philippe de Crévecoeur, the ducal governor of Picardy and Charles Biche, the late Duke’s chamberlain stayed and threw their support for her. Other ducal administrators consisted of Chancellor Hugonet, Lord Humbercourt and Lord Ravenstein. These three men were not popular, particularly the first two. The people hated Humbercourt for his cruelty and oppression of cities and Hugonet had been chief enforcer of Charles’s harsh taxation. Another ducal official in Ghent became the target of the people’s rage: Jan Van Melle, a corrupt tax collector who had enriched himself.

However, the biggest danger to Burgundy was France. Louis XI had immediately sprung into action after hearing about Nancy. French forces invaded the county of Burgundy, the palatinate of Burgundy, Macon and Charolais. All these places were far away from Ghent. The duchess was unable to aid with all her effort focusing on keeping the Flemish from erupting. While Louis could not claim all of Burgundy’s fief as Philip of Burgundy and little John prevented the claim that the Burgundian lands were forfeit to the French crown, he had no intentions of doing nothing. Louis focused on these regions, as well as supporting René of Lorraine, for his claim to Lorraine and Bar. In February the regions were overrun with French forces, and Margaret was unable to help them. Some French forces attacked Hainault and Luxemburg as well.

Burgundy at the time of Charles the Bold's death.

Margaret did gain a certain goodwill with the Estates from the Great Privilege and the french invasions did rally a larger amount of the Burgundian people to a unity. The burning of their villages did surprisingly not endear the victims to Louis forces and the loss of farms and supplies in winter made the delegates of Hainault and Luxemburg, especially, to fiercely support their dowager duchess.

Margaret also reached out to various allies; ambassadors were dispatched to England, to Emperor Frederick III and even to Portugal, at the court of king Alfonso VI. The Portuguese crown prince John got a second son with his wife Eleanor of Viseu in April 14th 1477, a infante named Peter, named for the late duke of Coimbra, during the war with Castile and Aragon.

The marriage of Maximilian of Austria and Mary of Burgundy would be an alliance against France. Margaret also offered her daughter’s hand to the Prince of Wales, in exchange for an army to protect Burgundy. Louis did send a delegation to the dowager as well, with a proposal of marriage between Isabella of Burgundy and Charles, dauphin of France. In return Louis offered his niece Catherine of Navarre’s hand to Philip of Burgundy. Margaret turned that down, hoping for her brother’s support against France.

Catherine of Navarre

The turbulence in Ghent continued well until March. The Great Privilege had been accepted by the Estates, but the anger towards certain ducal officials did not subside. Margaret might be held in higher esteem and no one was willing to attack the pregnant dowager duchess, but the same could not be said for others. Humbercourt, Hugonet and Jan Van Melle, as well as Guillaume de Clugny, the papal Pronotary soon found themselves as targets. All four men were arrested early in March and Melle’s house plundered by its wealth. Despite Margaret’s attempts of creating a proper trial, the men were sentenced to death and beheaded in public in late March.

The bloodletting seemed to have calmed down the Flemish people, as their most hated officials had faced justice. In April, a week after his eight birthday, Philip of Burgundy was sworn in as Duke of Flanders at the St Nicholas Church. The public appearance of the young duke and the pregnant Margaret seemed to win a lot of the Flemish over, especially Philip who displayed a maturity and dignity far above his years.

One other notable ally of Margaret would be Jehan van Dadizele. Jehan was the lieutenant general of Flanders and an important member of the Flemish nobility. He had been one of the negotiators when the Estates received the Great Privilege and defended the Flemish rights. A trusted and able man of Flanders, he requested a meeting with the dowager duchess, the great council and duke Philip. The meeting took place in mid-April and he offered the ducal family his council in exchange for the rights of Flanders to be upheld.

Margaret accepted him as advisor and Jehan gave the young Philip his pledge, in return Philip swore to upheld the rights as his liege lord. Jehan would be a prominent member of Philip’s regency, keeping order in Flanders, much to public relief.

Note: Jehan was otl murdered in 1481, probably on the orders of archduke Maximilian, who tried to circumvent the Flemish rights, something that backfired on him. Here he survives and becomes a councillor to Philip and Margaret, so the Flemish situation is much better.

In April 1477 Maximilian began the slow journey towards the Low Countries. Margaret and the emperor had managed to settle the marriage arrangement between him and Mary. Despite Mary no longer being the heiress of the Low Countries, she was still a desirable bride. And a rich one, Margaret had promised a dowry of 150, 000 crowns as well gold plate, jewellery and other valuable possessions. In return the Hapsburg would provide military resources to Burgundy’s defence. The prestige of Mary’s imperial marriage was important.

The Estates General had been hard pressed by the delegates of Hainault, among others, to raise a force strong enough to repel the French invaders in february. The estates agreed to raise a force of 50,000 men, around 13,000 had been levied in March. The new force attacked the French at Hainault and after spring, the area had been freed of invaders. Louis XI directed the remaining men to move back to Luxemburg. However, the French army had not been freed of trouble either. Dysentery had spread among the men and even in France, there were increased voices that his attack on Burgundy was unfunded. He had no rights to any fief belonging to the late Duke since Charles the Bold had male heirs at his death. One prominent action was Pope Sixtus IV sending an embassy to Paris to protest his invasion. The threat of excommunication was included. In result Louis had to withdraw from Luxemburg in summer of 1477. Despite that the military continued in the county of Burgundy, Charolais and Macon for a long while.

Margaret was able to depart Ghent in late May. She moved to her dower town of Binche in Hainault, despite being six months pregnant. Her three children came with her on the journey while Mary remained in Ghent.

In Binche Margaret accomplished several goals; she met with the Hainault council as well as the leading officials in her dower town and Philip was sworn in as Count of Hainault in the neighbouring city of Mons in mid-June. The presence of the young duke and their beloved dowager provided a huge rally and the province of Hainault finally kicked the French out in July. When she arrived in Binche Margaret had also organised an impressive and solemn service in the late duke’s memory. The ceremony took place at night with a long procession of torchbearers winding through the city, who had been clad in black velvet.

The Town Hall where Philip was sworn in as Count of Hainault

The dowager had paid for twenty pauper’s mourning clothes who took part in the ceremony. She and the children travelled with the train, little John carried by a nurse, Philip on horseback. Margaret and Isabella sat in an open carriage, both in black fur-lined gowns.

However, in the early days of July Margaret could no longer be as active as she used to be. She stayed in Mons and on the 5th of July she gave birth to her late husband’s final child: A daughter named Margaret.

By July Margaret was able to receive the French army at Hainaults surrender. Several captains had been taken prisoners by the Burgundians and weapons and pieces of artillery fell into their hands as well. In exchange for his war captains, Louis freed the Count of Chimay and Olivier de La Marche who had been taken ransom after Nancy. La Marche was a important courtier and he would remain one of the dowager’s most trusted men.

Margaret stayed at Mons with her children and baby Margaret until late September when she and her family moved to Malines (modern day Mechelen). The four ducal children needed a safe home for the foreseeable future, particularly John and the girls. Malines was a excellent choice for residence. Brabant was a more loyal region to the ducal rulers, rather than Flanders and Malines itself was centrally placed among Margaret’s dower towns. The city was guarded by walls and moats, making it easily defended. It had a reputation for being clean and livestock was not allowed to wander free. The ports were busy with traffic and the large population could sustain the industrial and commercial prosperity. Lacemaking provided work for the women of the city, as well as carpet weaving. Manufacturers of glass, pottery and leatherworks domineered the industry. Malines also had a reputation for metal crafts and armouries and bellmakers.

It was a ideal place for a ducal residence, but one problem remained. Malines did not have a ducal palace. Margaret solved that by purchasing the property of the bishop of Tournai. She also brought the seven adjourning houses and their land. The city of Malines welcomed their ducal family and she received around 3, 000 florins to bear up the expenses. Isabella, John and baby Margaret finally had a proper home. Philip would not stay in Malines at much as his siblings, until 1485 he travelled with his mother.

Mary of Burgundy and Maximilian of Austria

Margaret left her three youngest children in Malines and returned to Ghent in October. She and Philip had to attend the marriage of Archduke Maximilian and Mary. The young Austrian man had arrived in Ghent at late September. His journey had been very slow, most likely to levy the men and weapons that had been the terms for his marriage. Mary had remained in Ghent and had meet with the estates to aid in any further trouble. She had also gathered her dowry for the marriage. Around 40,000 crowns, almost half one third of the promised 150,000 had been collected when her groom arrived. To add to that, many gold and silver plates, jewellery and valuable tapestries were also included.

Maximilian entered Ghent escorted by 700 horsemen and around 11, 000 men. The army itself was Maximillian’s gift to Burgundy and one of the terms for the wedding. The duchess and young Philip received the army when they arrived in October.

The arrival of a imperial army both gladdened and worried the Flemish cities. They did not want further war with France and was weary of Hapsburg politics in the duchy. However, a army, that they did not have to be even more taxed for, would help. Maximilian’s charming manner did cause some suspicions about him trying to influence Philip.

Furthermore, his annunciation that he would stay until spring in Flanders did not sit well with the people. The archduke would try to rule Burgundy with german and Austrian interests, it was said among the street. Duke Philip was still very young. Mary and Maximilian married in St Bavo’s Cathedral in October. The logistics of the travel back home to Vienna demanded a longer stay, but Maximilian did not stay until spring. He would find his attempts to insert himself in the council, or in Philip’s circle hard to do and Mary had successfully gathered further 30, 000 crowns by new year of 1477. The archduke and his bride left Ghent in the second week of January, to reach Vienna and the Austrian heartlands in mid-May.

In Vienna Mary’s first child was born on the 3th of September. A son named Charles. The remainder of the dowry would be paid over the course of the next two years. Her second child, named Eleanor for Maximilian’s mother, was born in 1479, on November 10th.

Hofburg Castle in Vienna. This remained the seat of the Hapsburgs and Charles of Austria was born here in September 1478.

"Margaret and Mary would never see each other again, but they would keep in close contacts through diplomats and letters. Margaret’s education of Mary and her firm hand in crisis set a example for her step-daughter that would remain prominent for the remainder of her life"

-Source: Empress Mary of Burgundy, Stephan Kolner.

With her stepdaughter having left for Austria, Margaret and Philip would remain in Flanders until spring. They left for Hesdins in March to be closer to the Somme. The imperial marriage had enraged Louis XI of France and after Christmas he targeted the Somme towns, a region that had long been twisted by the dukes of Burgundy and France. At Hesdins, Margaret sent a delegation to London to try to get her brother, Edward IV of England to act. She also took around 5,000 men to repel the French invaders. The delegates of Picardy and Artois also backed their duke and around 2, 500 additional men joined the fighting.

The ducal embassy to England met with difficulties in their negotiations. Margaret had offered her son Philip’s hand to Mary of York, Edward’s second daughter. The old idea of a marriage between Isabella of Burgundy and Edward, prince of Wales also resurged. Edward was enthusiastic about a double marriage between England and Burgundy, but his sister was hesitant. To make things even worse, Edward seemed to have little to no intention of paying a dowry for Mary. He was still very attached to his French pension from the Treaty of Picquigny. In exchange for Mary he offered a invasion of France in return for a Burgundian pensions, something that Margaret doubted would occur.

Edward, Prince of Wales.

Finally, after two months of negotiations, an agreement was made. Isabella of Burgundy was betrothed to her cousin, the Prince of Wales. The marriage would take place at her 15th birthday in 1486. She would bring a dowry of 120, 000 crowns and in return the Burgundians could raise 10, 000 archers from England.

Margaret was able to gather 3, 000 ones before summer and they joined forces with the men at Somme. By autumn the French had been repelled from Somme, much to people’s relief.

After the victory Philip was sworn in as Count as Artois and Picardy at St Omer. The nine year old Duke had by now learned his first practical lessons in governance and military tactics.

Philip of Burgundy in 1478. One of the few portraits that had survived of his childhood

The young duke is seen wearing the Order of the Golden Fleece around his neck, a order started by his grandfather Philip the Good in 1430. Unknown artist.

The losses in the Somme had taught Louis XI a lesson; The county of Burgundy would become his sole prize. He focused his effort once more on that region and Charolais and Macon as well. The duchy of Lorraine had become Duke René’s once more, so any Burgundian influence was permanently lost there.

Louis efforts of winning over the estates of Burgundy was in full swing by 1479. He offered generous conditions towards the councils. Lenient taxations, a less corrupt government and privileges to the merchant community. Already in Charles the Bold’s time there had been a drift in that region towards France, so the plan had a good chance of succeeding. Despite that there was still a large community staying loyal to the ducal rulers and they protested heavily against the invasions. The Estates General were not able to defend the county efficiently, due to Lorraine blocking the way for reinforcements. Louis also sent emissaries to the Grand Council, once again bringing up a match between Isabella of Burgundy and Charles, the dauphin as a peace treaty.

The council had mixed receptions to that treaty. On one hand it would resolve the problems with France, but on the other, the county of Burgundy belonged rightfully to Duke Philip. The terms were also more favourable to France, being just losses for the duchy. The dauphin was also still betrothed to Elizabeth of York, the oldest daughter of Edward IV. And Isabella of Burgundy was the future princess of Wales.

The Flemish cities reacted positively to the French proposal. To sweeten the deal with Burgundy further, Louis offered his niece Catherine of Navarre to Duke Philip, even promising an impressive dowry for her. Margaret however was not convinced and refused the offer. In the summer of 1479 negotiations had reached a standstill. Louis decided to press the dowager further, sending two letters bearing his terms for a treaty. One was for Margaret and the other was to the Estates in Flanders.

Louis terms for peace contained the following:

Isabella of Burgundy would be betrothed to the Dauphin, and be raised in France until the wedding (Louis wanted the marriage to take place when she turned 13).

Her dowry would be the County of Burgundy, The Palatine of Burgundy, Charolais and Macon.

Philip would be betrothed to Catherine of Navarre, Louis’s niece. The king of France would provide a good dowry for her.

Margaret’s full dower lands would be restored to her.

Louis renounced all French claims to the other Burgundian fiefs, acknowledging Philip’s inheritance.

Margaret initially turned the treaty down, not wanting to give her daughter to the French. She was determined to regain the Burgundy regions. Unfortunately, this time the dowager played straight into Louis hands.

After hearing her rejection, Louis send a delegation to Ghent, demanding to know why the dowager duchess was not open to negotiations. Perhaps the letter sent to her had been lost? The estates in Flanders sent representatives to Margaret to get to the mystery. Under pressure the dowager was forced to show that she had received the letter from Louis, causing the Flemish cities to erupt in anger. Now it looked like Margaret had been dishonest with the Estates, not wanting to negotiate out of stubborn pride.

This caused a uproar against the dowager and the Grand Council. Calls to end the war was shouted in the streets of Ghent and Brussels. The Flemish called for the custody of Philip to be removed from the dowager as well. Facing enormous pressure by the people, Margaret and the Grand Council were forced into open negotiations with the King of France.

In October the Treaty of Arras was struck between Burgundy and France. Louis terms was agreed upon, with a few small changes, the marriage would take place at Isabella’s 15th birthday, not the 13th. Isabella would also keep a few Burgundians in her household, among those a couple of ladies chosen by her mother. The future dauphine would leave for France in 1480, not at once as Louis had desired. However, those changes were not of great importance to him. He succeeded in his goals at last.

Once the treaty of Arras had been made by both parties, the anger towards the dowager lessened. Jehan van Dadizele, the lieutenant General of Flanders had been once of the chief negotatiors with France and he reassured the the Flemish people that the dowager would keep her word. Duke Philip would stay with his mother.

Isabella of Burgundy in 1481, the painting was made by Jean Hey. A miniature portrait was sent to her mother Margaret the same year.

Margaret spent Christmas and the early spring with her daughters’ constant company. Preparations for her journey to France included an updated trousseau with clothing, gold and silver plates, tapestries and other possessions. Records for the dowager’s expenses shows cloth of gold and silver being ordered, fine Rennes linen, scarlet, purple and green velvets and blue and pink silks, along with the payments for tailors and shoemakers.

As a bibliophile Margaret also ensured that her daughter would leave with plenty of literature of different genres. The introduction of the printing press earlier would ensure that Margaret lived in a court of living authors. A few of the books given to Isabella came from her mother.

-Les Chroniques de Flandre, a book about the history of Flanders. Perhaps a reminder to her daughter of her heritage.

-La Somme le Roi, a sermon from a famous theologian Father Laurent du Bois, popular at court.

-Vie de St Colette, a religious work about St Colette.

-Recueil des Histories de Troie, (Collection of the stories of Troy), a copy of the book Margaret had gotten by William Caxton, who had introduced the printing press in England. Margaret had been his patron.

-Le Livre de la Cité des Dames, (The book of the city of ladies), the classic work of Christine de Pizan.

Margaret also employed a jewelsmith to make a collection of jewelry for her daughter. Necklaces of gold with rubies and diamond rings, as well as collar of white roses with pearls was included in her belongings.

Isabella showed a tendency of clinginess to her mother and oldest brother during these preparations, perhaps anxiety for the separation. Leaving her little siblings, John and Margaret was especially hard. Isabella had doted on them ever since they were born and in the nursery of Malines. The reputation of Louis XI as a father in law seemed to scare her. To Isabella, growing up with her duchy nearly constantly at war with France, the king had taken the form of a giant spider or a demon with horns and three eyes. Her inquiries about the dauphin got better results. Charles was described as a intelligent boy with charm.

Charles VIII of France

It was said that the miniature picture of Isabella that Charles received left the prince with positive feelings towards his fiancé.

In late March Isabella left with her mother and the entourage towards France. She was accompanied to Reims, where the royal delegates meet them at the cathedral. John II, duke of Bourbon, Anne of France, the eldest daughter of Louis XI and the bishop of Reims. Her arrival was celebrated as a alliance of peace by the French people. Isabella was handed over before the cathedral and publicly acclaimed as the Dauphine of France. The betrothal was blessed by the bishop of Reims inside the cathedral.

Isabella and Margaret spent three days together in Reims, to make sure that all the belongings got transferred and to let the Burgundians rest before the journey home. Margaret learned too her relief that Isabella’s education as dauphine would be handled by Anne of France, a capable and tall woman, who seemed kind to the little princess. After the three days the dowager duchess returned to Burgundy with her people.

Unlike with her stepdaughter, Margaret would see her daughter again and she would receive letters from Anne of France and Isabella. But nevertheless, the loss of her oldest girl would sting for a long while.

Anne of France, duchess of Bourbon. Louis daughter and the caretaker to Isabella of Burgundy.

He must think her slower than molasses.In exchange for Mary he offered a invasion of France in return for a Burgundian pensions,

Couldn't this be interpreted as an acknowledgment of independence?Louis renounced all French claims to the other Burgundian fiefs, acknowledging Philip’s inheritance.

Otl Edward offered the same thing.

Truth to be told Louis does not have a legal excuse to take the fiefs with a male heir so this is how it goes goes ittl.

And note that some of Margaret's councilors are people who abandoned Mary otl at this time. This time they stuck around given she was not the heiress so the internal conflicted is different.

Truth to be told Louis does not have a legal excuse to take the fiefs with a male heir so this is how it goes goes ittl.

And note that some of Margaret's councilors are people who abandoned Mary otl at this time. This time they stuck around given she was not the heiress so the internal conflicted is different.

I will be honest, with the focus on marriages and possible suitors a-brew all last week I was worried that the timeline would get bogged down entirely on matters of lineage. But, with these last two updates you made clear that you were paying attention to other affairs of the state (dealing with the local nobles and of course, the Burgundian Wars, shame Charles the Bold didn't pull through  ) while still focusing on the timeline's main running topic of royal weddings. Kudos!

) while still focusing on the timeline's main running topic of royal weddings. Kudos!

Shame the Free County of Burgundy (Franche-Comte) didn't stay in Philip's inheritance. It is technically part of the Holy Roman Empire and so I would have thought perhaps that fact might have made the French be more willing to leave it in Margaret's hands. The Duchy of Burgundy, Charolais, and Macon are all French and have no such excuse, but I really like the shape of a long Burgundy stretching from the Low Countries, through Lorraine and ending at the Franche-Comte. Not to mention that with France taking the County, Austria and France have a border at Alsace...

Though managing to keep the Somme lands should provide a nice buffer for them AND the English at Calais... Will those lands be known as the County of Picardy, including the lands of Ponthieu, Amiens, and Vermandois? Or are they separate titles and thus separate governates? Actually, could we get a run-down of titles Philip would inherit?

The last updates didn't mention Charles taking Guelders and Zutphen, are those both assumed to be in their control as IOTL?

And one last dynastic thing: any chance we'll see the line of Burgundy-Nevers become relevant? Though Nivernais is now deep in French territory, the County of Eu and the County of Rethel are right on the borders of the main Burgundian line...

(That's enough questions for now, I'll save my cultural questions for later~)

Shame the Free County of Burgundy (Franche-Comte) didn't stay in Philip's inheritance. It is technically part of the Holy Roman Empire and so I would have thought perhaps that fact might have made the French be more willing to leave it in Margaret's hands. The Duchy of Burgundy, Charolais, and Macon are all French and have no such excuse, but I really like the shape of a long Burgundy stretching from the Low Countries, through Lorraine and ending at the Franche-Comte. Not to mention that with France taking the County, Austria and France have a border at Alsace...

Though managing to keep the Somme lands should provide a nice buffer for them AND the English at Calais... Will those lands be known as the County of Picardy, including the lands of Ponthieu, Amiens, and Vermandois? Or are they separate titles and thus separate governates? Actually, could we get a run-down of titles Philip would inherit?

The last updates didn't mention Charles taking Guelders and Zutphen, are those both assumed to be in their control as IOTL?

And one last dynastic thing: any chance we'll see the line of Burgundy-Nevers become relevant? Though Nivernais is now deep in French territory, the County of Eu and the County of Rethel are right on the borders of the main Burgundian line...

(That's enough questions for now, I'll save my cultural questions for later~)

Good work on the update BlueFlower, but with all of the original Burgundian territory gone can Burgundy still call itself Burgundy

Couldn't this be interpreted as an acknowledgment of independence?

I read it the same way.

Fair enough though I’m sure it’ll irritate the French pride to no end which will no doubt bring some joy to the rulers of Burgundy. I’m excited to see where it goes from here especially as the race for colonies heats up.It did otl so I think the name will stick.

pass the popcorn!Fair enough though I’m sure it’ll irritate the French pride to no end which will no doubt bring some joy to the rulers of Burgundy. I’m excited to see where it goes from here especially as the race for colonies heats up.

It did otl so I think the name will stick.

Perhaps as "the Burgundian lands/inheritance", maybe, much like how we refer to the Hapsburg's lands occasionally as the Hapsburg Empire. But a more interesting spin on would be if Philip retains the name so that he can lay claim to the original lands and retake them at a later time. Perhaps the terminology of a Lower Burgundy becomes used instead, referring to the Low Countries while Upper Burgundy is for the Duchy and County.

I will be honest, with the focus on marriages and possible suitors a-brew all last week I was worried that the timeline would get bogged down entirely on matters of lineage. But, with these last two updates you made clear that you were paying attention to other affairs of the state (dealing with the local nobles and of course, the Burgundian Wars, shame Charles the Bold didn't pull through) while still focusing on the timeline's main running topic of royal weddings. Kudos!

Shame the Free County of Burgundy (Franche-Comte) didn't stay in Philip's inheritance. It is technically part of the Holy Roman Empire and so I would have thought perhaps that fact might have made the French be more willing to leave it in Margaret's hands. The Duchy of Burgundy, Charolais, and Macon are all French and have no such excuse, but I really like the shape of a long Burgundy stretching from the Low Countries, through Lorraine and ending at the Franche-Comte. Not to mention that with France taking the County, Austria and France have a border at Alsace...

Though managing to keep the Somme lands should provide a nice buffer for them AND the English at Calais... Will those lands be known as the County of Picardy, including the lands of Ponthieu, Amiens, and Vermandois? Or are they separate titles and thus separate governates? Actually, could we get a run-down of titles Philip would inherit?

The last updates didn't mention Charles taking Guelders and Zutphen, are those both assumed to be in their control as IOTL?

And one last dynastic thing: any chance we'll see the line of Burgundy-Nevers become relevant? Though Nivernais is now deep in French territory, the County of Eu and the County of Rethel are right on the borders of the main Burgundian line...

(That's enough questions for now, I'll save my cultural questions for later~)

Gosh, thank you so much for liking it! I have to admit that I can get bogged down into marriage plans too much (guilty pleasure), so I'm happy that I got back on track!

Now questions! Sorry for the late response, I had a evening thing at my work, so I could not respond until now.

Once I looked at the map properly at all of Charles the Bold's posessions, I knew that the county of Burgundy, Charolais and Macon would be the best targets for louis, geographically, they are the hardest to defend with Lorraine lying between them. So those are lost to the duchy. This treaty of Arras left the burgundians with a lot more that otl, the losses were bigger at that time.

The somme lands will be keept by Philip. And yes, I plan for those areas to be merged with the region of picardy. The Burgundy duchy itself are a congreation (is that the right word? A bunch of different regions under the lordship of a duke? native english speakers, help me out!) of different regions, but Duke of Burgundy was the universe title. Philip's true title is Philip IV of Burgundy.

The full titles of Philip is:

Duke of Burgundy, of Brabant, Limbourg, Luxembourg and Guelders, Count of Flanders and of Artois, of Vermandois, of Hainault, Holland and Zeeland, Namur and Zupthen, Marquess of the Holy Roman Empire, Lord of Friesland and Malines.

I think that is the total title after the Treaty of Arras.

Guelders and Zupthen are under Burgundian control as otl. I have a different relationship between Charles Von Egmont and Philip planned. Otl Maximilian screwed up for Guelders, here he had no ability to do so.

I'm not sure if Burgundy-Nevers line will be relevant. Perhaps the nevers line will die out earlier and Philip will take the titles? Would that be doable?

Last edited:

Also in case anyone noticed it, John II of Portugal has a second son named Infante Peter born in 1477 now. Make of that what you will.

Also I have more questions for the future of this TL. I don't know every detail of some matters, so I'm hoping others knows more.

-How likely is a marriage between Philip of Burgundy and Catherine of Navarre?

-What is the benefits, economically, mercantile, and otherwise for a non Hapsburg Burgundy?

-While we do know the benefits that Spain gets from no flemish-hapsburgs ruling them, what is the benefits and cons for the low countries without Spain. The cloth trade between the flemish cities and spain, for example. If the spanish decides to manufacture it themselves, how would that impact Burgundy? What other manufacturing choices can Burgundy pursue?

-How likely is a marriage between Philip of Burgundy and Catherine of Navarre?

-What is the benefits, economically, mercantile, and otherwise for a non Hapsburg Burgundy?

-While we do know the benefits that Spain gets from no flemish-hapsburgs ruling them, what is the benefits and cons for the low countries without Spain. The cloth trade between the flemish cities and spain, for example. If the spanish decides to manufacture it themselves, how would that impact Burgundy? What other manufacturing choices can Burgundy pursue?

Catherine of Navarre is also a claimant to the Duchy of Burgundy, so the marriage between Philip and Catherine solves close ends.

I didn't know that about Catherine of Navarre.

Would postponing Francis Phoebus's death make the marriage possible? Like until 1493 perhaps?

Would postponing Francis Phoebus's death make the marriage possible? Like until 1493 perhaps?

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 57 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 47 - Edmund the Grouch-back Chapter 48 - Keeping up with the Stewarts Chapter 49 - I'm rather lost at the moment Chapter 50 - We resume events in Burgundy in 1517 Chapter 51 - The Grand Duchy of Brabant - 1505- 1512 Author's update. Regarding the ethics of rewriting chapters Edits update regarding rewamping Final chapter update

Share: