There’s an elephant in the room. There’s always one in the room with Marianne Jean-Baptiste. That same old elephant; where have you been all these years? Actually, the answer is simple. The actress, Oscar-nominated for her quietly heart-breaking Hortense in Mike Leigh’s Secrets & Lies, has been living in Los Angeles, working away (notably as an FBI agent in the long-running television series Without a Trace, and bit parts in movies), bringing up her family, living the good life. It’s the question that is more delicate – why did she leave in the first place?

In 2013, Jean-Baptiste returned to the UK to play uncompromising pastor Margaret in the National Theatre’s The Amen Corner. Last year she was back again, in the second series of Broadchurch, as toughie barrister Sharon Bishop. And now she’s here to star in the premiere of debbie tucker green’s hang, at the Royal Court, an intense three-hander set in the near future.

Does this mean she’s back for good? She grins, and shakes her head vigorously. “No, I’m just doing this.” From her expression, she might as well be saying not on your nelly. I ask her what hang is about. “The play is set in a system where the victim of crime has a say in the form of punishment.” She comes to an abrupt and resolute stop.

What’s the crime? “Can’t say.”

Give us a clue. “No.”

I tell her she’s a spoilsport. “Well, you’re spoiling it for the paying public.”

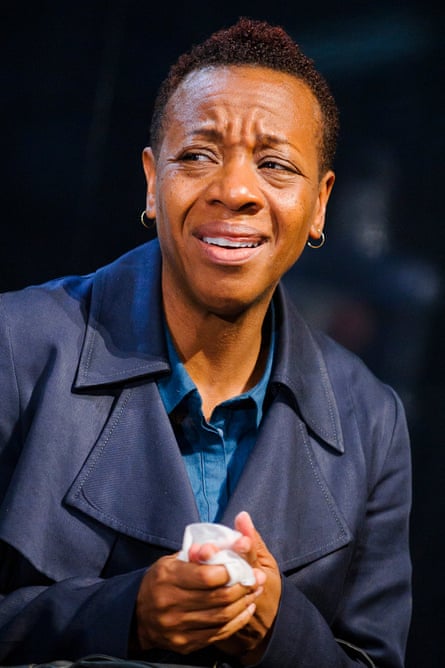

Jean-Baptiste knows how to stand her ground, and can be fabulously combative. She looks like a punk version of her former self – mini-mohican, grey tracksuit, trainers, buckets of attitude. She’d be scary if it weren’t for the raucous laugh that erupts on a regular basis – such as when I ask her if she’ll be back for another series of Broadchurch. “That character went to Broadchurch, did what she had to do and left. I can’t imagine her buying a little bungalow up there. D’ya know what I mean? Hehehehehe! Would be nice, though.” After all her years in America, she sounds more south London than ever.

Marianne Ragipcean Jean-Baptiste grew up in Peckham with an Antiguan mother, who worked in an old people’s home, and St Lucian father (hence the French name), who was a foreman for an events company. She was bright, went to grammar school, dreamed of being a barrister, but ended up at Rada, where she gained a classical education in music.

She spent most of her 20s in the theatre – then came Secrets & Lies, for which she became Britain’s first black Oscar nominee. Jean-Baptiste appeared to have everything ahead of her. She was just shy of 30, supremely versatile, with a chameleon face and an ability to segue from high farce to downbeat naturalism. We waited for the great roles and reviews and awards. And we waited and waited.

In 1996, Secrets & Lies won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. A year later, on British Screen’s 50th anniversary, the funding body invited 50 of the UK’s top actors to the festival – Jean-Baptiste wasn’t among them. She was pissed off, and let us know it. She told the Guardian that she regarded it as a snub, had burst into tears when she heard, and had been offered nothing since Secrets & Lies. She said: “The old men running the industry just have not got a clue. They’ve got to come to terms with the fact that Britain is no longer a totally white place where people ride horses, wear long frocks and drink tea. The national dish is no longer fish and chips, it’s curry.”

And that was that. She said she didn’t want to be regarded as chippy. But it was too late. By then Jean-Baptiste had morphed from the brilliant young black actress to the chippy black actress that nobody wanted to cast. While all she had done was tell it straight.

In 1997, she wrote the music for Leigh’s film Career Girls. And, in 1999, she gave another great performance, playing Doreen Lawrence in The Murder of Stephen Lawrence with such muted conviction it was hard to believe it wasn’t documentary. And then she packed her bags for America.

In the intervening years she has rarely talked about race. You sense she regretted her past candidness; that she felt it had come to define her. Today, I tell her I expected to see her in loads of British movies after Secrets and Lies. She gives me a look. “That would have been great. But I’m not a film-maker. I didn’t want to relocate at first.”

Where were all the offers? “In the States. So that’s what happened. You know it’s a fickle industry.”

But British films were doing well back then? There’s a tension. She knows what I’m getting at, and she doesn’t want to go there. Soon enough she challenges me directly. “What d’you want me to say? Let’s get to that point. What d’you want me to say?”

Why you weren’t getting offers over here, I say.

She holds out her hands, palms up, in frustration. “I can’t tell you why I’ve not been invited to a party. You need to go to the host and say, ‘Why didn’t you invite her to the party?’”

The tension is tangible. She seems angry – with me, and maybe with herself. “Oh God, are we going to do this boring shit? Really? Honestly?” Why is it boring shit? “Because it’s so talked about. It’s been written about.” Why, she asks, every time she is interviewed, is she expected to answer this; why has she got to be the spokeswoman for black actors? But she knows the answer. Because, I say, nobody has been affected as obviously, or as dramatically as you have, and ...

Before I complete my sentence she does so for me. “Because I was the first person to say anything about it.”

She’s het up, and I’m het up. Look, it might be boring for you, I say, but it’s relevant because 18 years on from your Oscar nomination, things are as bad as ever; Britain’s ethnic mix is not reflected in our arts.

“It’s the gatekeepers!” she shouts back.

And America’s not much better. I mention Lupita Nyong’o – yes, she won an Oscar for Twelve Years a Slave, but she’s barely worked in the two years since (though she is in the new Star Wars). “It is what it is. It’s the old guard, it’s the way things are done. It’s people not being in the position where they can think in a broader sense.” We still seem to be talking in code.

Is what happened to her and Nyong’o racism?

Silence. I count the seconds. Seven, eight, nine, 10. Even after all this time it is obvious just how painful this subject is to her. Thirteen, 14, 15 seconds. Eventually she answers.

“Opportunity. There needs to be more film directors of colour. They bandy about the word diversity a lot, but when I say of colour, I mean Asian, black, I mean people of all colour. We need to have those voices given the opportunity, not told that their films will not be distributed or will not sell well abroad. It’s a very, very tricky subject, and it’s one that I’m tired of. I’m really tired of it because I can read an interview with any number of white actors and actresses and they speak about process and about the script and about their castmates and about the journey, but every time you read an interview with a black actor it’s the same stuff they get asked over and over again. And I don’t know how much talk can be had about something that existed before I got involved in the business to now. We still talk about it. But not a lot is done. Not a lot done.” She sounds exhausted.

I apologise for having shouted. She grins. “It’s all right. I love a bit of passion. Throw it at me, baby. It’s about the gatekeepers, it’s not about the people shouting.”

The thing is, she says, she doesn’t want to be portrayed as a victim because she isn’t one. “It’s not this sob story. I had a choice. I could have stayed and fought it out, but I thought you know what, this is madness, it’s like fishing in a river and seeing people grabbing fishes upstream and you’re still down there going, ‘This is where I need to be, this is my spot.’ You fucking walk up stream and you catch your fish. I’m a member of the African diaspora, my parents left the Caribbean and came to London for a better life. We moved. And you print that, with the expletives.”

Was Jean-Baptiste, now 48, surprised by the the way she was treated? “I grew up in Peckham, south-east London, I understood the animal I was dealing with because I’d seen other things with actors on a smaller scale. It was the success that was the surprise.”

I ask if she suffered because she wasn’t a conventional dolly bird.

“How dare you! ‘I’m not not a bloody dolly bird!’ I am!”

Now I’m embarrassed. You’re a beautiful woman, I say, but you don’t conform to the stereotype. She roars. “Hahahaha! Oh my God.”

I have another theory, I say. You didn’t play the game. A year after Secrets & Lies, she had the first of her two children with her husband, former ballet dancer Evan Williams. Ah well, she says, that wasn’t deliberate, and anyway there are so many positives that have come out of her career. She still recalls the thrill of the Oscars . Is it true that Juliette Binoche, who won the best supporting actress, told Jean-Baptiste she deserved to win it? “She may have said something like that,” she says coyly. “I don’t remember a lot of what happened that night. You’re sat there, four rows from the front, Celine Dion is belting out a song louder than a fucking trumpet, Goldie Hawn comes up to you and tells you she loves your work. You’re like, what work?! D’you know what I mean? And there’s Anjelica Huston and you’re just going, oh my God, oh my God, oh my God!”

And if she hadn’t struggled in Britain she wouldn’t have discovered LA. “It was alien at first. I remember driving to the mall so we could walk about. But now I absolutely love it. I love the weather, the space, the quiet, the sea, I love the mountains, the light. I’m a real light junkie.” She admits she had a tendency towards bleakness when in Britain, and that has gone now. Not least because of her kids, aged 17 and 13. “I could be very solitary before. Withdrawn. I’d say to myself, OK, you can stay in bed for the day, maybe another day, then get your arse up. But now they’re like, get out of bed, I want something to eat.”

I ask about her heroes, and she mentions her parents and sister. Has she got any political heroes? She thinks, and belly laughs. “My temptation is to say something really fucking naughty like Gaddafi, but somebody will take it seriously.” Does she consider herself political? Well, she says, she’s never voted Republican or Conservative, so yes she supposes so.

She starts to quote Martin Niemöller, struggling to remember it. “First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out – Because I was not a Socialist. / Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out – Because I was not a Trade Unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out – Because I was not a Jew. / Then they came for me – and there was no one left to speak for me.”

She pauses. “He’s my hero.” Yes, she says it is important to speak out. “But sometimes you get tired saying the same thing over and over and over again, and hearing the same thing over and over and over again.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion