José Clemente Orozco – The Murals of José Clemente Orozco

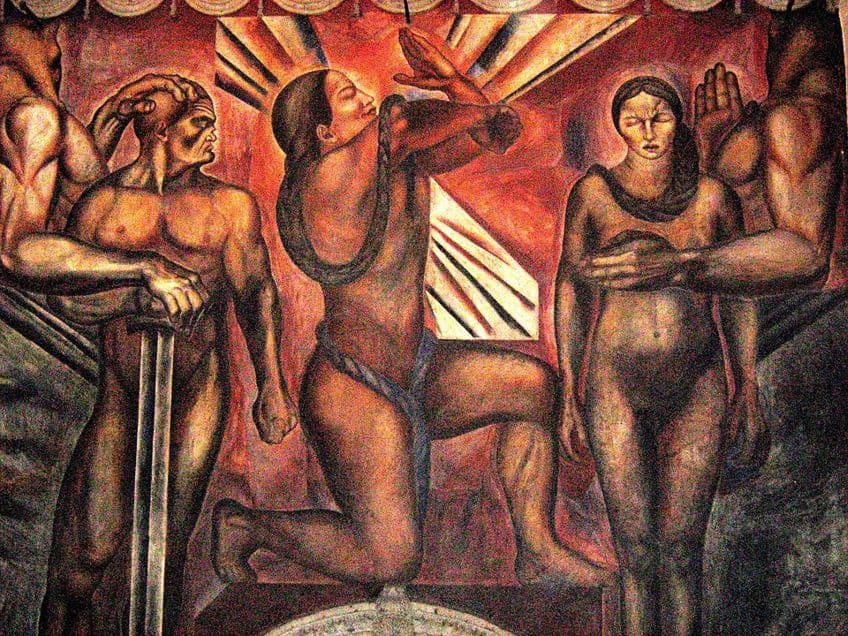

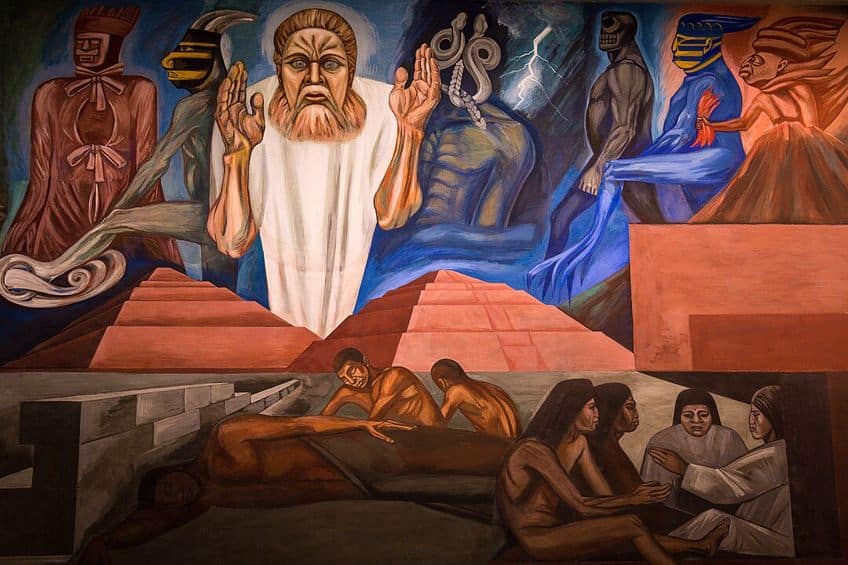

Out of the three great Mexican muralists, José Clemente Orozco was often considered the least revered, mainly due to what many regarded as a pessimistic and introverted nature. Unlike the other two muralists, Diego Rivera and David Siqueiros, Orozco was known for being openly critical of the Mexican Revolution and the government that followed. The style of José Clemente Orozco’s paintings combined traditional Renaissance-era modeling and compositions, emotionally charged abstract modernism, often dark, dreary hues, and motifs and iconography derived from pre-colonial, indigenous, and pre-European artwork. The muralist movement in Mexico as a whole emphasized the significance of large-scale public artwork, and Orozco’s murals provided a platform for powerful and openly visible political and social commentary.

Table of Contents

The Biography of José Clemente Orozco

| Artist Name | José Clemente Orozco |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Date of Birth | 23 November 1883 |

| Date of Death | 7 September 1949 |

| Place of Birth | Zapotlán, Mexico |

José Clemente Orozco, together with Siqueiros and Rivera, restored the Italian Renaissance fresco painting tradition with large-scale murals intended to attract a larger audience. Their aim was to establish a more democratic art form, in other words, to make their work – with its post-Mexican Revolution, patriotic subjects – accessible to individuals of all socioeconomic classes. Orozco was also commissioned to create murals throughout the United States. Orozco’s avant-garde, expressionist approach, paired with the rebirth of Social Realism by the Mexican Muralists, influenced American painters such as Philip Guston, Jackson Pollock, Jacob Lawrence, and Ben Shahn.

Childhood

One of four brothers, José Clemente Orozco grew up in Jalisco, Mexico’s southwestern province. Along with being the editor for the daily La Abeja, his father owned an ink, soap, and coloring plant. His mother was a homemaker who often taught painting workshops to the women of the town. In order to improve their financial circumstances, the family relocated initially to Guadalajara and then later to Mexico City.

Despite their best intentions, though, conditions were harsh for middle-class families, and it was sometimes impossible to make ends meet every month.

As a young boy, while walking to and from school, he would regularly walk past the store where José Guadalupe Posada, a politically motivated cartoonist known for his depictions of skeletons and skulls, worked in plain view from the street. Fascinated, Orozco began experimenting with sketching and coloring, later describing seeing Posada’s artwork as his “awakening” to the world of art. Orozco then started taking drawing classes during the evening.

Education

Later, for financial reasons, he was compelled to pursue agricultural engineering. Only after the passing of his father did Orozco completely commit to pursuing an artistic career. A shocking choice given that he had lost his left hand in 1904 while managing explosives for Independence Day celebrations. Because most doctors were on vacation, by the time he was eventually treated, gangrene had set in and it meant having to remove his entire hand. Orozco attended the San Carlos Academy full-time from 1906 to 1914, where he joined future muralist and fellow student, David Alfaro Siqueiros in the student strike of 1911.

Orozco met Gerardo Murillo, a somewhat older artist who often recounted intriguing accounts of his trips in Europe, during night courses at the Academy. Gerardo Murillo was a staunch supporter of fostering a uniquely Mexican art style and strongly objected to the Academy’s requirement of replicating European styles. Orozco started playing around with Mexican landscapes and incorporating familiarly brilliant colors into his works of art with the confidence that Murillo instilled in his younger students. This served as the initial seed that eventually grew into Mexico’s cultural liberation.

Early Period

Orozco started his career as a caricaturist for several dissident journals. He was given a solo exhibit of his watercolors, The House of Tears, featuring men beyond their prime and female prostitutes. Orozco’s attention to human suffering was a prominent motif in his earliest works, maybe serving as a mirror to his own personal struggles. Despite this acknowledgment of his creative ability, he found himself painting dolls to make ends meet. During the Mexican Revolution’s bloody conflicts, Orozco worked as an artist for the pro-Carranza journal La Vanguardia. He observed the Revolution’s devastation firsthand, something that would permanently define his art and substantially contribute to his negative attitude toward life.

Orozco, unlike Siqueiros and Rivera, was an anarchist. He was strongly anti-military, anti-institution, anti-clerical, and anti-establishment since he believed that all of these institutions were intrinsically corrupt.

From 1917 to 1919, Orozco lived in the United States, mostly making money painting signs in San Francisco and subsequently in New York. He encountered Siqueiros on his way to Europe one night and went to supper with him and Xavier Guerrero, where they debated over the future of Mexican art. He went back to Mexico in 1920, where he was given his first official commission as part of the new government’s attempt to convey themes of contemporary Mexican identity at the National Preparatory School. In 1923, he married Margarita Valladares, with whom he had three children. Orozco’s acquaintances in the arts valued him considerably in the years that followed. Despite receiving recognition from this small intellectual elite, he was widely overlooked in his own country. In 1927, Orozco left his family to pursue a career in America, where he observed firsthand the devastating consequences of the Great Depression.

He befriended the arts patron and journalist Alma Reed, who fell deeply in love with a governor in Mexico while on a business trip to Mexico, only to learn he had been assassinated during the Revolution when she was back in the United States to make preparations for their wedding. Alma Reed welcomed Orozco to intellectual gatherings and displayed his paintings in her home. On one of these occasions, the Greek Orthodox patriarch of New York recognized the majesty of classical antiquity in Orozco’s art and honored him with a symbolic laurel wreath. During his time in the United States, he created some of his most renowned murals, including those in Pomona, and the Museum of Modern Art.

Mature Period

Orozco visited Europe for the first time in 1932, visiting all of the obligatory museum locations. He then returned to Mexico as a well-known artist and created his masterwork at the Hospicio Cabanas in Guadalajara, which has been dubbed the “Sistine Chapel of the Americas” and has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage site. Orozco’s technical skill was demonstrated by his use of the famously unforgiving fresco method on the wall without first drawing the mural.

His preliminary sketches were always created on paper, never on the murals themselves.

He was regarded as a very reserved individual who preferred his own company and working in solitude from his studio, virtually the polar opposite of his friend and occasional adversary, Diego Rivera. Orozco met Gloria Campobello, the prima dancer of the Mexico City Ballet, in around 1943 for whom he eventually left his first wife. The pair resided in New York until 1946 when Campobello unexpectedly decided to leave the relationship and Orozco subsequently moved back to Mexico to live alone.

Later Period

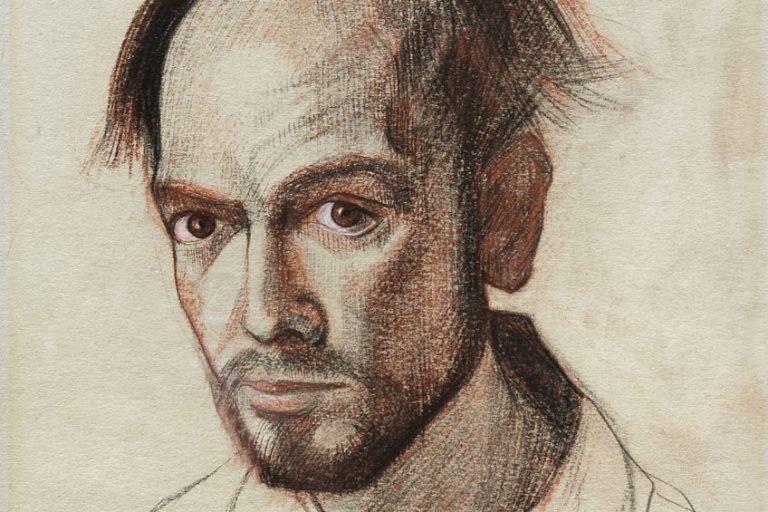

In the 1940s, José Clemente Orozco’s paintings comprised several portraits as well as a series of anti-military and anti-clerical artworks. Orozco received the National Prize in 1946 for his murals at the Church of the Hospital of Jesus. At the invitation of Nobel Prize-winning author John Steinbeck, he produced the illustrations for The Pearl in 1947. He held a large retrospective show in Mexico’s most prominent museum, the Palacio de Bellas Artes, the same year. Orozco’s self-portraits help us understand his personality on a deeper level. He portrays himself as an academic and a serious individual of profound thought.

His eyes have the penetrating sharpness of a witness who has been witness to some of our species’ most heinous tendencies. One could imagine him outraged or depressed but it’s difficult to identify any joy in his expression. One of his friends even said that they had never seen the artist smile in the entire time they knew him. In 1949, he finished his last fresco. He passed away from heart failure while asleep at the age of 65.

The Legacy of José Clemente Orozco’s Paintings

Orozco’s perspectives on the Mexican Revolution were markedly different from those of Rivera and Siqueiros. Unlike the optimistic Rivera or the assertive Siqueiros, he had a significantly cynical view of the revolution; he was very disturbed by the vast destruction and death toll, and suspicious of the revolution’s ability to serve those who, irrespective of the powers that prevailed, appeared to suffer. Orozco’s early works focused on human misery, no doubt as a result of the traumas he had experienced and observed in his own life.

He was infamous for his inability to establish relationships with ordinary folks on a one-on-one basis, but he was filled with profound compassion for mankind as a whole.

Perhaps strangely, his greatest contribution is that he criticized the very nationalist attitude that brought him fame. Gustavo Arias Murueta, Rico Lebrun, Joan Mitchell, Luis Nishizawa, and Eleanor Coen are among the artists who have been influenced by José Clemente Orozco’s Paintings. Furthermore, Orozco’s work impacted an early period of Jackson Pollock’s art, while he was attending Jungian therapy sessions with a Jungian psychiatrist. Philip Guston and Pollock even went on an artistic pilgrimage to view Orozco’s Epic of American Civilization together. Pollock also stated that Prometheus was America’s best modern artwork.

The Style of José Clemente Orozco’s Paintings

His work is distinguished by compelling and dramatic imagery, issues related to society and politics, and a skillful balance of reality and symbolism. José Clemente Orozco’s paintings typically portray misery, conflict, and the human condition. The use of vivid and intense colors is one of Orozco’s distinguishing characteristics. He used a rich palette with vibrant colors that created a striking visual impact and provoked powerful emotions. His color choices tended to be symbolic, representing the depth of human misery, political tyranny, and Mexico’s turbulent past.

His paintings often include individuals in exaggerated or deformed shapes, highlighting their mental and emotional circumstances. Orozco’s compositions were meticulously designed to captivate the observer and evoke a sense of motion and energy. He often used metaphor and symbolism to communicate certain political and social ideas. Orozco addressed themes of death, pain, identity, and the complex nature of the human experience using symbols like masks, skulls, crosses, and hands. These symbols provided deeper levels of significance and urged audiences to consider the work’s deeper meaning. Orozco’s works additionally demonstrated his mastery of chiaroscuro. He used this approach to masterfully heighten the dramatic effect of his compositions, producing tension and contrasting shadows and light.

Orozco portrayed post-revolutionary Mexico in a strongly expressionistic style, focusing on peasants and the struggle between classes, the trials of ordinary life, social revolution, conflicts, and women during wartime. Negative reactions to his paintings from moralists and critics persuaded him to go to America in 1917. When he returned to Mexico in 1920, the Mexican muralist movement had officially begun, and President Alvaro Obregón’s new administration was eager to support José Clemente Orozco’s paintings. During the following years, his work attained monumentality unrivaled in Mexican art. In the artist’s later years, he was acknowledged as a national hero in Mexico, and was seen as a leader among those who elevated his country’s art to international prominence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was José Clemente Orozco?

José Clemente Orozco was a well-known Mexican muralist who, along with David Siqueiros and Diego Rivera, is regarded as having a pivotal role in the Mexican muralism movement. He traveled to Europe and examined the artwork of the great artists of the Renaissance era, where he became acquainted with numerous art movements. When he returned to Mexico, Orozco got entangled in the Mexican Revolution, which significantly affected both his creative and political ideas.

What Were José Clemente Orozco’s Paintings Known For?

Orozco’s paintings were large-scale public murals. They are comparable in style and technique to the frescoes that the artists in the Renaissance used to make. His themes usually revolved around the suffering and challenges of the Mexican people.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “José Clemente Orozco – The Murals of José Clemente Orozco.” Art in Context. July 5, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/jose-clemente-orozco/

Meyer, I. (2023, 5 July). José Clemente Orozco – The Murals of José Clemente Orozco. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/jose-clemente-orozco/

Meyer, Isabella. “José Clemente Orozco – The Murals of José Clemente Orozco.” Art in Context, July 5, 2023. https://artincontext.org/jose-clemente-orozco/.