Maltese language

Last updated| Maltese | |

|---|---|

| Malti | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈmɐːltɪ] |

| Native to | Malta |

| Ethnicity | Maltese |

Native speakers | 570,000 (2012) [1] |

Early form | |

| Dialects | |

| Latin (Maltese alphabet) Maltese Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Malta European Union |

| Regulated by | National Council for the Maltese Language Il-Kunsill Nazzjonali tal-Ilsien Malti |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | mt |

| ISO 639-2 | mlt |

| ISO 639-3 | mlt |

| Glottolog | malt1254 |

| Linguasphere | 12-AAC-c |

| | |

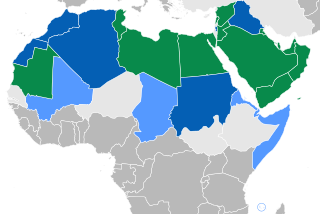

Maltese (Maltese: Malti, also L-Ilsien Malti or Il-Lingwa Maltija) is a Semitic language derived from late medieval Sicilian Arabic with Romance superstrata spoken by the Maltese people. It is the national language of Malta [3] and the only official Semitic and Afroasiatic language of the European Union. Maltese is a Latinised variety of spoken historical Arabic through its descent from Siculo-Arabic, which developed as a Maghrebi Arabic dialect in the Emirate of Sicily between 831 and 1091. [4] As a result of the Norman invasion of Malta and the subsequent re-Christianization of the islands, Maltese evolved independently of Classical Arabic in a gradual process of latinisation. [5] [6] It is therefore exceptional as a variety of historical Arabic that has no diglossic relationship with Classical or Modern Standard Arabic. [7] Maltese is thus classified separately from the 30 varieties constituting the modern Arabic macrolanguage. Maltese is also distinguished from Arabic and other Semitic languages since its morphology has been deeply influenced by Romance languages, namely Italian and Sicilian. [8]

Contents

- History

- Demographics

- Classification

- Dialects

- Phonology

- Consonants

- Vowels

- Historical phonology

- Orthography

- Alphabet

- Written Maltese

- Samples

- Vocabulary

- Romance

- Siculo-Arabic

- Berber

- English

- Calendar

- Time

- Question words

- Sample phrases[54]

- Grammar

- Adjectives and adverbs

- Nouns

- Article

- Verbs

- Media

- Code-switching

- See also

- Footnotes

- Notes

- References

- Further reading

- External links

The original Arabic base comprises around one-third of the Maltese vocabulary, especially words that denote basic ideas and the function words, [9] but about half of the vocabulary is derived from standard Italian and Sicilian; [10] and English words make up between 6% and 20% of the vocabulary. [11] A 2016 study shows that, in terms of basic everyday language, speakers of Maltese are able to understand around a third of what is said to them in Tunisian Arabic and Libyan Arabic, [12] which are Maghrebi Arabic dialects related to Siculo-Arabic, [13] whereas speakers of Tunisian Arabic and Libyan Arabic are able to understand about 40% of what is said to them in Maltese. [14] This reported level of asymmetric intelligibility is considerably lower than the mutual intelligibility found between other varieties of Arabic. [15]

Maltese has always been written in the Latin script, the earliest surviving example dating from the late Middle Ages. [16] It is the only standardised Semitic language written exclusively in the Latin script. [17]

History

The origins of the Maltese language are attributed to the arrival, early in the 11th century, of settlers from neighbouring Sicily, where Siculo-Arabic was spoken, reversing the Fatimid Caliphate's conquest of the island at the end of the 9th century. [18] This claim has been corroborated by genetic studies, which show that contemporary Maltese people share common ancestry with Sicilians and Calabrians, with little genetic input from North Africa and the Levant. [19] [20]

The Norman conquest in 1091, followed by the expulsion of the Muslims, complete by 1249, permanently isolated the vernacular from its Arabic source, creating the conditions for its evolution into a distinct language. [18] In contrast to Sicily, where Siculo-Arabic became extinct and was replaced by Sicilian, the vernacular in Malta continued to develop alongside Italian, eventually replacing it as official language in 1934 , alongside English. [18] The first written reference to the Maltese language is in a will of 1436, where it is called lingua maltensi. The oldest known document in Maltese, Il-Kantilena (Xidew il-Qada) by Pietru Caxaro, dates from the 15th century. [21]

The earliest known Maltese dictionary was a 16th-century manuscript entitled "Maltese-Italiano"; it was included in the Biblioteca Maltese of Mifsud in 1764, but is now lost. [22] A list of Maltese words was included in both the Thesaurus Polyglottus (1603) and Propugnaculum Europae (1606) of Hieronymus Megiser, who had visited Malta in 1588–1589; Domenico Magri gave the etymologies of some Maltese words in his Hierolexicon, sive sacrum dictionarium (1677). [21]

An early manuscript dictionary, Dizionario Italiano e Maltese, was discovered in the Biblioteca Vallicelliana in Rome in the 1980s, together with a grammar, the Regole per la Lingua Maltese, attributed to a French Knight named Thezan. [22] [23] The first systematic lexicon is that of Giovanni Pietro Francesco Agius de Soldanis, who also wrote the first systematic grammar of the language and proposed a standard orthography. [22]

Demographics

This section appears to contradict another section of this article.(February 2024) |

Ethnologue reports a total of 530,000 Maltese speakers: 450,000 in Malta and 79,000 in the diaspora. Most speakers also use English. [1]

The largest diaspora community of Maltese speakers is in Australia, with 36,000 speakers reported in 2006 (down from 45,000 in 1996, and expected to decline further). [24]

The Maltese linguistic community in Tunisia originated in the 18th century. Numbering several thousand in the 19th century, it was reported to be only 100 to 200 people as of 2017. [25]

Classification

Maltese is descended from Siculo-Arabic, a Semitic language within the Afroasiatic family, [26] that in the course of its history has been influenced by Sicilian and Italian, to a lesser extent French, and more recently English. Today, the core vocabulary (including both the most commonly used vocabulary and function words) is Semitic, with large numbers of loanwords. [10] Because of the Sicilian influence on Siculo-Arabic, Maltese has many language contact features and is most commonly described as a language with a large number of loanwords. [27]

The Maltese language has historically been classified in various ways, with some claiming that the ancient Punic language (another Semitic language) was its origin instead of Siculo-Arabic, [21] [28] [29] while others believed the language to be one of the Berber languages (another family within Afroasiatic). [21] The Kingdom of Italy classified it as regional Italian. [30]

Dialects

Urban varieties of Maltese are closer to Standard Maltese than rural varieties, [31] which have some characteristics that distinguish them from Standard Maltese.

They tend to show some archaic features [31] such as the realisation of ⟨kh⟩ and ⟨gh⟩ and the imāla of Arabic ā into ē (or ī especially in Gozo), considered archaic because they are reminiscent of 15th-century transcriptions of this sound. [31] Another archaic feature is the realisation of Standard Maltese ā as ō in rural dialects. [31] There is also a tendency to diphthongise simple vowels, e.g., ū becomes eo or eu. [31] Rural dialects also tend to employ more Semitic roots and broken plurals than Standard Maltese. [31] In general, rural Maltese is less distant from its Siculo-Arabic ancestor than is Standard Maltese. [31]

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ʔ | |||||

| Affricate | t͡s | d͡z | t͡ʃ | d͡ʒ | ||||||||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | ħ | |||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||||||

Voiceless stops are only lightly aspirated and voiced stops are fully voiced. Voicing is carried over from the last segment in obstruent clusters; thus, two- and three-obstruent clusters are either voiceless or voiced throughout, e.g. /niktbu/ is realised [ˈniɡdbu] "we write" (similar assimilation phenomena occur in languages like French or Czech). Maltese has final-obstruent devoicing of voiced obstruents and word-final voiceless stops have no audible release, making voiceless–voiced pairs phonetically indistinguishable in word-final position. [34]

Gemination is distinctive word-medially and word-finally in Maltese. The distinction is most rigid intervocalically after a stressed vowel. Stressed, word-final closed syllables with short vowels end in a long consonant, and those with a long vowel in a single consonant; the only exception is where historic *ʕ and *ɣ meant the compensatory lengthening of the succeeding vowel. Some speakers have lost length distinction in clusters. [35]

The two nasals /m/ and /n/ assimilate for place of articulation in clusters. [36] /t/ and /d/ are usually dental, whereas /t͡sd͡zsznrl/ are all alveolar. /t͡sd͡z/ are found mostly in words of Italian origin, retaining length (if not word-initial). [37] /d͡z/ and /ʒ/ are only found in loanwords, e.g. /ɡad͡zd͡zɛtta/ "newspaper" and /tɛlɛˈviʒin/ "television". [38] The pharyngeal fricative /ħ/ is velar ([ x ]), uvular ([ χ ]), or glottal ([ h ]) for some speakers. [39]

Vowels

Maltese has five short vowels, /ɐɛɪɔʊ/, written a e i o u; six long vowels, /ɐːɛːɪːiːɔːʊː/, written a, e, ie, i, o, u, all of which (with the exception of ie/ɪː/) can be known to represent long vowels in writing only if they are followed by an orthographic għ or h (otherwise, one needs to know the pronunciation; e.g. nar (fire) is pronounced /naːr/); and seven diphthongs, /ɐɪɐʊɛɪɛʊɪʊɔɪɔʊ/, written aj or għi, aw or għu, ej or għi, ew, iw, oj, and ow or għu. [5]

Historical phonology

The original Arabic consonant system has undergone partial collapse under European influence, with many Classical Arabic consonants having undergone mergers and modifications in Maltese: [40]

| Classical Arabic | ت/t/ | ط/tˤ/ | ث/θ/ | د/d/ | ض/dˤ/ | ذ/ð/ | ظ/ðˤ/ | س/s/ | ص/sˤ/ | ح/ħ/ | خ/x~χ/ | ع/ʕ/ | غ/ɣ~ʁ/ | ق/q/ | ه/h/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maltese | /t/ | /d/ | /s/ | /ħ/ | /ʕ/ | /ʔ/ | /k/ | /∅/ | ||||||||

Orthography

Alphabet

This section needs editing to comply with Wikipedia's Manual of Style. In particular, it has problems with punctuation and text styling in the table.(October 2022) |

The modern system of Maltese orthography was introduced in 1924. [41] Below is the Maltese alphabet, with IPA symbols and approximate English pronunciation:

| Letter | Name | IPA (Alphabet Name(s)) | Maltese example | IPA (orthographically representing) | Approximate English pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A a | a | aː | anġlu (angel) | ɐ,aː,æː | similar to 'u' in nut in RP; [aː] similar to father in Irish English; [æː] similar to cat in American English, in some dialects it may be [ɒː] in some locations as in what in some American English Dialects |

| B b | be | beː | ballun (ball) | b | bar, but at the end of a word it is devoiced to [p]. |

| Ċ ċ | ċe | t͡ʃeː | ċavetta (key) | t͡ʃ | church (note: undotted 'c' has been replaced by 'k', so when 'c' does appear, it is to be spoken the same way as 'ċ') |

| D d | de | deː | dar (home) | d | day, but at the end of a word it is devoiced to [t]. |

| E e | e | eː | envelopp (envelope) | eː,ɛ,øː,ə | [e:] somewhat like face in Northern England English [ɛ]end when short, it is often changed to [øː,œ] when following and more often when followed by a w, when at the end in an unstressed syllable it is pronounced as schwa [ə,Vᵊ] comma |

| F f | effe | ɛf(ː)ᵊ | fjura (flower) | f | far |

| Ġ ġ | ġe | d͡ʒøː | ġelat (ice cream) | d͡ʒ | gem, but at the end of a word it is devoiced to [tʃ]. |

| G g | ge | geː | gallettina (biscuit) | ɡ | game, but at the end of a word it is devoiced to [k]. |

| GĦ għ | ajn | ajn,æːn | għasfur (bird) | (ˤ)ː, ħː | has the effect of lengthening and pharyngealising associated vowels (għi and għu are [i̞(ˤ)j] (may be transcribed as [ə(ˤ)j]) and [oˤ]). When found at the end of a word or immediately before 'h' it has the sound of a double 'ħ' (see below). |

| H h | akka | ak(ː)ɐ | hu (he) | not pronounced unless it is at the end of a word, in which case it has the sound of 'ħ'. | |

| Ħ ħ | ħe | ħeː,heː,xe: | ħanut (shop) | ħ | no English equivalent; sounds similar to /h/ but is articulated with a lowered larynx. |

| I i | i | iː | ikel (food) | i̞ː,iː,ɪ | [i̞ː] bite (the way commonly realized in Irish English or [iː] in other words as beet but more forward) and when short as [ɪ] bit, occasionally 'i' is used to display il-vokali tal-leħen(the vowel of the voice) as in words like l-iskola or l-iMdina ,in this case it takes the schwa sound. |

| IE ie | ie | iːᵊ,ɛː | ieqaf (stop) | ɛː,iːᵊ | sounds similar to yield or RP near, or opened up slightly towards bed or RP square |

| J j | je | jə,jæ,jɛ | jum (day) | j | yard |

| K k | ke | kə,kæ,kɛ | kelb (dog) | k | kettle |

| L l | elle | ɛl(ː)ᵊ | libsa (dress) | l | line |

| M m | emme | ɛm(ː)ᵊ | mara (woman) | m | march |

| N n | enne | ɛn(ː)ᵊ | nanna (granny) | n | next |

| O o | o | oː | ors (bear) | o,ɔ,ɒ | [o] as in somewhere between similar to Scottish English o in no[ɔ] like 'aw' in RP law, but short or [ɒ] as in water in some American dialects. |

| P p | pe | peː,pə | paġna (page, sheet) | p | part |

| Q q | qe | ʔø,ʔ(ʷ)ɛ,ʔ(ʷ)æ,ʔ(ʷ)ə | qattus (cat) | ʔ | glottal stop, found in the Cockney English pronunciation of "bottle" or the phrase "uh-oh" /ʔʌʔoʊ/. |

| R r | erre | ɛɹ(ː)ᵊ,æɹ(:)ᵊ,ɚ(ː)ᵊ or ɛr(ː)ᵊ,ær(:)ᵊ,ər(ː)ᵊ | re (king) | r,ɹ | [r] as in General American English butter, or ɹ road (r realization changes depending on dialect or location in the word.) |

| S s | esse | ɛs(ː)ᵊ | sliem (peace) | s | sand |

| T t | te | teː | tieqa (window) | t | tired |

| U u | u | uː,ʉ | uviera (egg cup) | u,ʉ,ʊ | [u] as in General American English boot or in some dialects it may be realized as [ʉ] as in some American English realizations of student, short u is [ʊ] put |

| V v | ve | vøː,veː,və | vjola (violet) | v | vast, but at the end of a word it is devoiced to [f] may be said as [w] in the word Iva(yes) sometimes this is just written as Iwa. |

| W w | ve doppja /u doppja/we | vedɒp(ː)jɐ,uːdɒp(ː)jɐ,wøː | widna (ear) | w | west |

| X x | xe | ʃə,ʃøː | xadina (monkey) | ʃ/ʒ | shade, sometimes as measure; when doubled the sound is elongated, as in "Cash shin" vs. "Cash in". |

| Ż ż | że/żeta | zə,zø:,ze:t(ɐ) | żarbun (shoe) | z | maze, but at the end of a word it is devoiced to [s]. |

| Z z | ze | t͡sə,t͡søː,t͡seːt(ɐ) | zalza (sauce) | t͡s/d͡z | pizza |

Final vowels with grave accents (à, è, ì, ò, ù) are also found in some Maltese words of Italian origin, such as libertà ("freedom"), sigurtà (old Italian: sicurtà, "security"), or soċjetà (Italian: società, "society").

The official rules governing the structure of the Maltese language are recorded in the official guidebook Tagħrif fuq il-Kitba Maltija (English: Knowledge on Writing in Maltese) issued by the Akkademja tal-Malti (Academy of the Maltese language). The first edition of this book was printed in 1924 by the Maltese government's printing press. The rules were further expanded in the 1984 book, iż-Żieda mat-Tagħrif, which focused mainly on the increasing influence of Romance and English words. In 1992 the academy issued the Aġġornament tat-Tagħrif fuq il-Kitba Maltija, which updated the previous works. [42]

The National Council for the Maltese Language (KNM) is the main regulator of the Maltese language (see Maltese Language Act, below). However, the academy's orthography rules are still valid and official.

Written Maltese

Since Maltese evolved after the Italo-Normans ended Arab rule of the islands, a written form of the language was not developed for a long time after the Arabs' expulsion in the middle of the thirteenth century. Under the rule of the Knights Hospitaller, both French and Italian were used for official documents and correspondence. During the British colonial period, the use of English was encouraged through education, with Italian being regarded as the next-most important language.

In the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century, philologists and academics such as Mikiel Anton Vassalli made a concerted effort to standardise written Maltese. Many examples of written Maltese exist from before this period, always in the Latin alphabet, Il-Kantilena from the 15th century being the earliest example of written Maltese. In 1934, Maltese was recognised as an official language.

Samples

The Maltese language has a tendency to have both Semitic vocabulary and also vocabulary derived from Romance languages, primarily Italian. Words such as tweġiba (Arab origin) and risposta (Italian origin) have the same meaning (answer) but can be and are both used in Maltese. Below are two versions of the same translations, one in vocabulary derived mostly from Semitic root words while the other uses Romance loanwords (from the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe , see p. 17):

| English | Maltese (Semitic vocabulary) | Maltese (Romance vocabulary) |

|---|---|---|

The Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities. These values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail. | L-Għaqda hija mibnija fuq is-siwi ta' għadir għall-ġieħ il-bniedem, ta' ħelsien, ta' għażil il-ġemgħa, ta' ndaqs bejn il-ġnus, tas-saltna tad-dritt [lower-alpha 1] u tal-għadir għall-ħaqq tal-bniedem, wkoll il-ħaqq ta' wħud li huma f'minoranzi. [lower-alpha 2] Dan is-siwi huwa mqassam bejn il-Pajjiżi [lower-alpha 3] Msieħba, f'nies li tħaddan il-kotrija, li ma tgħejjibx, li ddann, li tgħaqqad u li tiżen indaqs in-nisa u l-irġiel. | L-Unjoni hija bbażata fuq il-valuri tar-rispett għad-dinjità tal-bniedem, il-libertà, id-demokrazija, l-ugwaljanza, l-istat tad-dritt u r-rispett għad-drittijiet tal-bniedem, inklużi d-drittijiet ta' persuni li jagħmlu parti minn minoranzi. Dawn il-valuri huma komuni għall-Istati Membri f'soċjetà fejn jipprevalu l-pluraliżmu, in-non-diskriminazzjoni, it-tolleranza, il-ġustizzja, is-solidarjetà u l-ugwaljanza bejn in-nisa u l-irġiel. |

Below is the Lord's Prayer in Maltese compared to other Semitic languages (Arabic and Syriac) which cognates highlighted:

| English | Maltese [43] | Arabic (Romanised) [44] | Syriac (Romanised) [45] |

|---|---|---|---|

Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth, as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us; and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen | Missierna, li inti fis-smewwiet, jitqaddes ismek, tiġi saltnatek, ikun li trid int, kif fis-sema, hekkda fl-art. Ħobżna ta' kuljum agħtinallum. Aħfrilnadnubietna, bħalmanaħfru lil min hu ħati għalina. U la ddaħħalniex fit-tiġrib, iżda eħlisna mid-deni. Ammen | Abana, alladhifis-samawat, li yataqaddas ismuka, li ya’ati malakutuka, litakun mashi'atuka, kama fis-sama’ kadhlika 'ala al ard. khubzana kafafana 'atiinaalyawm, wa agfhir lanadhunubana, kamanaghfiru nahnu aidan lil mudnibin ilayna. Wa la tudkhilna fi tajariba, lakin najjina min ashiriir. Amin | Abun, d-bashmayo, nithqadashshmokh, tithe malkuthokh, nehwe sebyonokh aykano d-bashmayo oph bar`o. hab lan lahmo d-sunqonan yowmono washbuq lan hawbayn wahtohayn aykano doph hnan shbaqan l-hayobayn lo ta`lan l-nesyuno elo paso lan men bisho Amin |

Vocabulary

Although the original vocabulary of the language was Siculo-Arabic, it has incorporated a large number of borrowings from Romance sources of influence (Sicilian, Italian, and French) and, more recently, Germanic ones (from English). [46]

The historical source of modern Maltese vocabulary is 52% Italian/Sicilian, 32% Siculo-Arabic, and 6% English, with some of the remainder being French. [10] [47] Today, most function words are Semitic, so despite only making up about a third, they are the most used among Maltese people when conversing. In this way, it is similar to English, which is a Germanic language that had large influence from Norman French and Latin (58% of English vocabulary). As a result of this, Romance language-speakers may easily be able to comprehend more technical ideas expressed in Maltese, such as "Ġeografikament, l-Ewropa hi parti tas-superkontinent ta' l-Ewrasja" (Geographically, Europe is part of the Supercontinent of Eurasia), while not understanding a single word of a more basic sentence such as "Ir-raġel qiegħed fid-dar" (The man is in the house), which would be easily understood by any Arabic speaker.

Romance

An analysis of the etymology of the 41,000 words in Aquilina's Maltese-English Dictionary shows that words of Romance origin make up 52% of the Maltese vocabulary, [10] although other sources claim from as low as 40%, [11] to as high as 55%. This vocabulary tends to deal with more complex concepts. They are mostly derived from Sicilian and thus exhibit Sicilian phonetic characteristics, such as /u/ in place of /o/, and /i/ in place of /e/ (e.g. tiatru not teatro and fidi not fede). Also, as with Old Sicilian, /ʃ/ (English 'sh') is written 'x' and this produces spellings such as: ambaxxata/ambaʃːaːta/ ('embassy'), xena/ʃeːna/ ('scene' cf. Italian ambasciata, scena).

| Maltese | Sicilian | Italian | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| skola | scola | scuola | school |

| gvern | cuvernu | governo | government |

| repubblika | ripùbblica | repubblica | republic |

| re | re | re | king (Germanic) |

| natura | natura | natura | nature |

| pulizija | pulizzìa | polizia | police |

| ċentru | centru | centro | centre |

| teatru | tiatru | teatro | theatre |

A tendency in modern Maltese is to adopt further influences from English and Italian. Complex Latinate English words adopted into Maltese are often given Italianate or Sicilianate forms, [10] even if the resulting words do not appear in either of those languages. For instance, the words "evaluation", "industrial action", and "chemical armaments" become "evalwazzjoni", "azzjoni industrjali", and "armamenti kimiċi" in Maltese, while the Italian terms are valutazione, vertenza sindacale, and armi chimiche respectively. (The origin of the terms may be narrowed even further to British English; the phrase "industrial action" is meaningless in the United States.) This is also comparable to the situation with English borrowings into the Italo-Australian dialect. English words of Germanic origin are generally preserved relatively unchanged.

Some influences of African Romance on Arabic and Berber spoken in the Maghreb are theorised, which may then have passed into Maltese. [48] For example, in calendar month names, the word furar "February" is only found in the Maghreb and in Maltese – proving the word's ancient origins. The region also has a form of another Latin named month in awi/ussu < augustus. [48] This word does not appear to be a loan word through Arabic, and may have been taken over directly from Late Latin or African Romance. [48] Scholars theorise that a Latin-based system provided forms such as awi/ussu and furar in African Romance, with the system then mediating Latin/Romance names through Arabic for some month names during the Islamic period. [49] The same situation exists for Maltese which mediated words from Italian, and retains both non-Italian forms such as awissu/awwissu and frar, and Italian forms such as april. [49]

Siculo-Arabic

Siculo-Arabic is the ancestor of the Maltese language, [10] and supplies between 32% [10] and 40% [11] of the language's vocabulary.

| Maltese | Siculo-Arabic (in Sicilian) | Arabic text | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| bebbuxu | babbaluciu | ببوش (babbūš) | snail |

| ġiebja | gebbia | جب (jabb) | cistern |

| ġunġlien | giuggiulena | جنجلان (junjulān) | sesame seed |

| sieqja | saia | ساقية (sāqiyah) | canal |

| kenur | tannura | تنور (tannūr) | oven |

| żagħfran | zaffarana | زعفران (zaʿfarān) | saffron |

| żahra (less common than fjura, borrowed from Medieval Sicilian) | zagara | زهرة (zahrah) | blossom |

| żbib | zibbibbu | زبيب (zabīb) | raisins |

| zokk (may be borrowed from Sicilian) | zuccu | ساق (sāq) | tree trunk |

| tebut | tabbutu | تابوت (tābūt) | coffin |

Żammit (2000) found that 40% of a sample of 1,821 Quranic Arabic roots were found in Maltese, a lower percentage than found in Moroccan (58%) and Lebanese Arabic (72%). [50] An analysis of the etymology of the 41,000 words in Aquilina's Maltese-English Dictionary shows that 32% of the Maltese vocabulary is of Arabic origin, [10] although another source claims 40%. [11] [51] Usually, words expressing basic concepts and ideas, such as raġel (man), mara (woman), tifel (boy), dar (house), xemx (sun), sajf (summer), are of Arabic origin. Moreover, belles-lettres in Maltese tend to aim mainly at diction belonging to this group. [31]

The Maltese language has merged many of the original Arabic consonants, in particular the emphatic consonants, with others that are common in European languages. Thus, original Arabic /d/, /ð/, and /dˤ/ all merged into Maltese /d/. The vowels, however, separated from the three in Arabic (/aiu/) into five, as is more typical of other European languages (/aɛiou/). Some unstressed short vowels have been elided. The common Arabic greeting as salāmu 'alaykum is cognate with is-sliem għalikom in Maltese (lit. the peace for you, peace be with you), as are similar greetings in other Semitic languages (e.g. shalom ʿalekhem in Hebrew).

Since the attested vocabulary of Siculo-Arabic is limited, the following table compares cognates in Maltese and some other varieties of Arabic (all forms are written phonetically, as in the source): [52]

| Maltese | Cairene | Damascene | Iraqi | Negev (bedouin) | Yemenite (Sanaani) | Moroccan | Modern Standard Arabic | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qalb | 'alb | 'aleb | qalb | galb | galb | qalb | قلب (qalb) | heart |

| waqt | wa't | wa'et | waket | wagt | wagt | waqt | وقت (waqt) | time |

| qamar | 'amar | 'amar | qamaɣ | gumar | gamar | qmar | قمر (qamar) | moon |

| kelb | kalb | kaleb | kalb | čalb | kalb | kalb | كلب (kalb) | dog |

Berber

Like all Maghrebi Arabic dialects, Maltese has a significant vocabulary derived from Berber languages. Whether these words entered Maltese by being inherited from Siculo-Arabic or directly loaned Berber languages is not yet known. These include: [53]

| Maltese | Berber languages | English |

|---|---|---|

| gremxula | azrem ašal, lit. 'land worm', (Kabyle) | lizard |

| fekruna | tifakrunin (Jerbi), ifekran (Tashelhiyt), ifkran (Kabyle) | turtle |

| geddum | aqadum, lit. 'face, frown' (Kabyle) | chin |

| gendus | gandūz, lit. 'young calf' (Jerbi) | ox, bull |

| gerżuma | ageržum (Mozabite, Tashelhiyt) | throat |

| tfief | tilfaf (Ouargli), tifāf, tilfāf, tiffāf (Tarifit) | sow thistle ( Sonchus oleraceus ) |

| tengħud | talaɣūda (Tunisian Arabic), telɣūda (Algerian Arabic) | spurge ( Euphorbia ) |

| kosksu | kuskesu, kuskus (Kabyle) | couscous, small round pasta |

| fartas | aferḍas (Ouargli, Kabyle) | bald |

| għaffeġ | ‘affež (Algerian Arabic), effeẓ (Ouargli, Mozabite) | to crush, to squash |

| żrinġ | tažrant (Jerbi) | frog |

| żrar | zrar (Mozabite, Ouargli), azrar (Kabyle, Nafusi) | gravel |

| werżieq | wárẓag (Mrazig) | cicada, lit. screamer, shrieker |

| buqexrem | buqišrem (Kabyle) | vervain (Verbena officinalis) |

| fidloqqom | fudalɣem (Kabyle) | borage (Borago officinalis) |

| żorr | uzur (Kabyle), uzzur (Tarifit) | rude, arrogant |

| lellex | lelleš (Mozabite) | to shine, to glitter |

| pespes | bbesbes (Ouargli) | to whisper |

| teptep | ṭṭebṭeb (Ouargli) | to blink, to twinkle |

| webbel | webben (Mozabite) | to induce, to tempt |

English

It is estimated that English loanwords, which are becoming more commonplace, make up 20% of the Maltese vocabulary, [11] although other sources claim amounts as low as 6%. [10] This percentage discrepancy is due to the fact that a number of new English loanwords are sometimes not officially considered part of the Maltese vocabulary; hence, they are not included in certain dictionaries. [10] Also, English loanwards of Latinate origin are very often Italianised, as discussed above. English loanwords are generally transliterated, although standard English pronunciation is virtually always retained. Below are a few examples:

| Maltese | English |

|---|---|

| futbol | football |

| baskitbol | basketball |

| klabb | club |

| friġġ | fridge |

"Fridge" is a common shortening of "refrigerator". "Refrigerator" is a Latinate word which could be imported into Maltese as rifriġeratori, whereas the Italian word is frigorifero or refrigeratore.

Calendar

The days of the week (Maltese: jiem il-ġimgħa) in Maltese are referred to by number, as is typical of other Semitic languages, especially Arabic. Days of the week are commonly preceded by the word nhar meaning 'day'.

| English | Maltese | Literal |

|---|---|---|

| Sunday | Il-Ħadd | first [day] |

| Monday | It-Tnejn | second [day] |

| Tuesday | It-Tlieta | third [day] |

| Wednesday | L-Erbgħa | fourth [day] |

| Thursday | Il-Ħamis | fifth [day] |

| Friday | Il-Ġimgħa | gathering [day] |

| Saturday | Is-Sibt | Sabbath [day] |

The months of the year (Maltese: xhur is-sena) in Maltese are mostly derived from Sicilian, but Frar and Awwissu are possibly derived from African Romance through Siculo-Arabic.

| English | Maltese |

|---|---|

| January | Jannar |

| February | Frar |

| March | Marzu |

| April | April |

| May | Mejju |

| June | Ġunju |

| July | Lulju |

| August | Awwissu |

| September | Settembru |

| October | Ottubru |

| November | Novembru |

| December | Diċembru |

Time

| English | Maltese |

|---|---|

| today | illum |

| yesterday | ilbieraħ |

| tomorrow | għada |

| second | sekonda |

| minute | minuta (archaic: dqiqa) |

| hour | siegħa |

| day | jum or ġurnata |

| week | ġimgħa |

| month | xahar |

| year | sena |

Question words

| English | Maltese | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| What (standalone) | Xiex | Xiex? | What? |

| What (preceding) | X' | X' għamilt? | What did you do? |

| Who | Min | Min hu dak? | Who is he? |

| How | Kif | Kif inti llum? | How are you today? |

| Where | Fejn | Fejn sejjer? | Where are you going? |

| Where (from) | Mnejn | Mnejn ġie? | Where did he come from? |

| Why | Għala, Għaliex, Għalxiex, Ilgħala | Għala telaq? | Why did he leave? |

| Which | Liem, Liema | Liem wieħed hu tajjeb? | Which one is good? |

| When | Meta | Meta ħa titlaq? | When will you leave? |

| How Much | Kemm | Kemm jiswa dan? | How much does this cost? |

Sample phrases [54]

| English | Maltese |

|---|---|

| Hello. | Hello. |

| Yes. | Iva. |

| Yes please. | Iva, jekk jogħġbok. |

| No. | Le. |

| No thanks. | Le grazzi. |

| Please. | Jekk jogħġbok. |

| Thank you. | Grazzi. |

| Thank you very much. | Grazzi ħafna. |

| You're welcome. | M'hemmx imniex. |

| I'd like a coffee please. | Nixtieq kafè, jekk jogħġbok. |

| Two beers please. | Żewġ birer, jekk jogħġbok. |

| Excuse me. | Skużani. |

| What time is it? | X’ħin hu? |

| Can you repeat that please? | Tista' tirrepeti jekk jogħġbok? |

| Please speak more slowly. | Jekk jogħġbok tkellem iktar bil-mod. |

| I don't understand. | Mhux qed nifhem. |

| Sorry. | Skużani. |

| Where are the toilets? | Fejn huma t-toilets? |

| How much does this cost? | Kemm jiswa dan? |

| Welcome! | Merħba! |

| Good morning. | Bonġu. |

| Good afternoon. | Il-wara nofsinhar it-tajjeb. |

| Good evening. | Is-serata t-tajba. |

| Good night. | Il-lejl it-tajjeb. |

| Goodbye. | Saħħa. |

Grammar

Maltese grammar is fundamentally derived from Siculo-Arabic, although Romance and English noun pluralisation patterns are also used on borrowed words.

Adjectives and adverbs

Adjectives follow nouns. There are no separately formed native adverbs, and word order is fairly flexible. Both nouns and adjectives of Semitic origin take the definite article (for example, It-tifel il-kbir, lit. "The boy the elder"="The elder boy"). This rule does not apply to adjectives of Romance origin.

Nouns

Nouns are pluralised and also have a dual marker. Semitic plurals are complex; if they are regular, they are marked by -iet/-ijiet, e.g., art, artijiet "lands (territorial possessions or property)" (cf. Arabic -at and Hebrew -ot/-oth) or -in (cf. Arabic -īn and Hebrew -im). If irregular, they fall in the pluralis fractus (broken plural) category, in which a word is pluralised by internal vowel changes: ktieb, kotba " book", "books"; raġel, irġiel "man", "men".

Words of Romance origin are usually pluralised in two manners: addition of -i or -jiet. For example, lingwa, lingwi "languages", from Sicilian lingua, lingui.

Words of English origin are pluralised by adding either an "-s" or "-jiet", for example, friġġ, friġis from the word fridge. Some words can be pluralised with either of the suffixes to denote the plural. A few words borrowed from English can amalgamate both suffixes, like brikksa from the English brick, which can adopt either collective form brikks or the plural form brikksiet.

Derivation

As in Arabic, nouns are often derived by changing, adding or removing the vowels within a triliteral root. These are some of the patterns used for nouns: [55]

- CaCiC – xadin (monkey), sadid (rust)

- CCiC – żbib (raisin)

- CaCCa – baqra (cow), basla (onion)

- CeCCa – werqa (leaf), xewqa (wish)

- CoCCa – borka (wild duck), forka (gallows)

- CaCC – qalb (heart), sajd (fishing)

- CeCC – kelb (dog), xemx (sun)

- CCuCija – tfulija (childhood), xbubija (maidenhood)

- CCuCa – rtuba (softness), bjuda (whiteness)

- CaCCaC – tallab (beggar), bajjad (whitewasher)

The so-called mimated nouns use the prefix m- in addition to vowel changes. This pattern can be used to indicate place names, tools, abstractions, etc. These are some of the patterns used for mimated nouns:

- ma-CCeC – marden (spindle)

- mi-CCeC – minkeb (elbow), miżwed (pod)

- mu-CCaC – musmar (nail), munqar (beak)

Article

The proclitic il- is the definite article, equivalent to "the" in English and "al-" in Arabic.

The Maltese article becomes l- before or after a vowel.

- l-omm (the mother)

- rajna l-Papa (we saw the Pope)

- il-missier (the father)

The Maltese article assimilates to a following non-ġ coronal consonant (called konsonanti xemxin "sun consonants"), namely:

- Ċ iċ-ċikkulata (the chocolate)

- D id-dar (the house)

- N in-nar (the fire)

- R ir-razzett (the farm)

- S is-serrieq (the saw)

- T it-tifel (the child)

- X ix-xemx (the sun)

- Ż iż-żarbuna (the shoe)

- Z iz-zalzett (the sausage)

Verbs

Verbs show a triliteral Semitic pattern, in which a verb is conjugated with prefixes, suffixes, and infixes (for example ktibna, Arabic katabna, Hebrew kathabhnu (Modern Hebrew: katavnu) "we wrote"). There are two tenses: present and perfect. The Maltese verb system incorporates Romance verbs and adds Maltese suffixes and prefixes to them, for example; iddeċidejna "we decided" ← (i)ddeċieda "decide", a Romance verb + -ejna, a Maltese first person plural perfect marker.

An example would be the Semitic root X-M-X, which has something related to the sun, example: xemx (sun), xmux (suns), xemxi (sunny), xemxata (sunstroke), nixxemmex (I sunbathe), ma xxemmixtx (I didn't sunbathe), tixmix (the act of sunbathing). Maltese also features the stringing of verb suffixes indicating direction of action, for example; agħmilhomli "make them for me"← agħmel "make" in the imperative + hom from huma "them" + li suffix indicating first person singular; ħasletielu "she washed it for him"←ħaslet "she washed" from the verb ħasel "to wash" + ie the object + lu suffix indicating third person masculine singular.

Media

With Malta being a multilingual country, the usage of Maltese in the mass media is shared with other European languages, namely English and Italian. The majority of television stations broadcast from Malta in English or Maltese, although broadcasts from Italy in Italian are also received on the islands. Similarly, there are more Maltese-language radio programs than English ones broadcast from Malta, but again, as with television, Italian broadcasts are also picked up. Maltese generally receives equal usage in newspaper periodicals to English.

By the early 2000s, the use of the Maltese language on the Internet is uncommon, and the number of websites written in Maltese are few. In a survey of Maltese cultural websites conducted in 2004 on behalf of the Maltese Government, 12 of 13 were in English only, while the remaining one was multilingual but did not include Maltese. [56] In 2011, only 6.5 per cent of Maltese internet users reported employing Maltese online, which may be a consequence of the lack of online support for the language. [57]

Code-switching

The Maltese population, being fluent in both Maltese and English, displays code-switching (referred to as Maltenglish) in certain localities and between certain social groups. [10]

See also

Footnotes

Notes

- 1 2 Maltese at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ↑ Martine Vanhove, « De quelques traits prehilaliens en maltais », in: Peuplement et arabisation au Maghreb cccidental : dialectologie et histoire, Casa Velazquez - Universidad de Zaragoza (1998), pp.97-108

- ↑ "Constitution of Malta". Leġiżlazzjoni Malta. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ So who are the 'real' Maltese. Times of Malta. September 13, 2014. Archived from the original on 2016-03-12.

The kind of Arabic used in the Maltese language is most likely derived from the language spoken by those that repopulated the island from Sicily in the early second millennium; it is known as Siculo-Arab. The Maltese are mostly descendants of these people.

- 1 2 Albert J. Borg; Marie Azzopardi-Alexander (1997). Maltese. Routledge. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-415-02243-9.

In fact, Maltese displays some areal traits typical of Maghrebine Arabic, although over the past 800 years of independent evolution it has drifted apart from Tunisian and Libyan Arabic

- ↑ Brincat (2005): "Originally Maltese was an Arabic dialect but it was immediately exposed to Latinisation because the Normans conquered the islands in 1090, while Christianisation, which was complete by 1250, cut off the dialect from contact with Classical Arabic. Consequently Maltese developed on its own, slowly but steadily absorbing new words from Sicilian and Italian according to the needs of the developing community."

- ↑ Hoberman, Robert D. (2007). "Chapter 13: Maltese Morphology". In Kaye, Alan S. (ed.). Morphologies of Asia and Africa. Vol. 1. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrown. p. 258. ISBN 9781575061092. Archived from the original on 2017-09-30.

Maltese is the chief exception: Classical or Standard Arabic is irrelevant in the Maltese linguistic community and there is no diglossia.

- ↑ Hoberman, Robert D. (2007). "Chapter 13: Maltese Morphology". In Kaye, Alan S. (ed.). Morphologies of Asia and Africa. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrown. pp. 257–258. ISBN 9781575061092. Archived from the original on 2017-09-30.

yet it is in its morphology that Maltese also shows the most elaborate and deeply embedded influence from the Romance languages, Sicilian and Italian, with which it has long been in intimate contact.... As a result Maltese is unique and different from Arabic and other Semitic languages.

- ↑ Brincat (2005): "An analysis of the etymology of the 41,000 words in Aquilina's Maltese-English Dictionary shows that 32.41% are of Arabic origin, 52.46% are from Sicilian and Italian, and 6.12% are from English. Although nowadays we know that all languages are mixed to varying degrees, this is quite an unusual formula. However, the words derived from Arabic are more frequent because they denote the basic ideas and include the function words."

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Brincat (2005).

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Languages across Europe – Maltese, Malti". BBC. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "Mutual Intelligibility of Spoken Maltese, Libyan Arabic and Tunisian Arabic Functionally Tested: A Pilot Study". p. 1. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

To summarise our findings, we might observe that when it comes to the most basic everyday language, as reflected in our data sets, speakers of Maltese are able to understand less than a third of what is being said to them in either Tunisian or Benghazi Libyan Arabic.

- ↑ Borg, Albert J.; Azzopardi-Alexander, Marie (1997). Maltese. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-02243-6.

- ↑ "Mutual Intelligibility of Spoken Maltese, Libyan Arabic and Tunisian Arabic Functionally Tested: A Pilot Study". p. 1. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

Speakers of Tunisian and Libyan Arabic are able to understand about 40% of what is said to them in Maltese.

- ↑ "Mutual Intelligibility of Spoken Maltese, Libyan Arabic and Tunisian Arabic Functionally Tested: A Pilot Study". p. 1. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

In comparison, speakers of Libyan Arabic and speakers of Tunisian Arabic understand about two-thirds of what is being said to them.

- ↑ The Cantilena. 2013-10-19. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Il-Kunsill Nazzjonali tal-Ilsien Malti. Archived from the original on 2014-01-06.

Fundamentally, Maltese is a Semitic tongue, the same as Arabic, Aramaic, Hebrew, Phoenician, Carthaginian and Ethiopian. However, unlike other Semitic languages, Maltese is written in the Latin alphabet, but with the addition of special characters to accommodate certain Semitic sounds. Nowadays, however, there is much in the Maltese language today that is not Semitic, due to the immeasurable Romantic influence from our succession of (Southern) European rulers through the ages.

- 1 2 3 Brincat (2005)

- ↑ Felice, A. E. (5 August 2007). "Genetic origin of contemporary Maltese". Times of Malta . Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ↑ Capelli, C.; et al. (Mar 2006). "Population structure in the Mediterranean basin: a Y chromosome perspective". Ann. Hum. Genet. 70 (2): 207–225. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00224.x. hdl: 2108/37090 . PMID 16626331. S2CID 25536759.

- 1 2 3 4 L-Akkademja tal-Malti. "The Maltese Language Academy". Archived from the original on 2015-09-23.

- 1 2 3 Agius, D. A. (1990). "Reviewed Work: A Contribution to Arabic Lexical Dialectology by Al-Miklem Malti". Bull. Br. Soc. Middle East. Stud. 17 (2): 171–180. doi:10.1080/13530199008705515. JSTOR 194709.

- ↑ Cassola, A. (June 2012). "Italo-Maltese relations (ca. 1150–1936): people, culture, literature, language". Mediterr. Rev. 5 (1): 1–20. ISSN 2005-0836.

- ↑ "As at the 2006 Australian Census, the number of Australians speaking Maltese at home was 36,514, compared to 41,250 in 2001 and 45,243 in 1996. The 2006 figures represent a drop of 19.29% when compared with the 1996 figures. Given that many of those who speak Maltese at home are over the age of 60, the number of Maltese speakers will invariably go for a nosedive by 2016." Joseph Carmel Chetcuti, Why It's time to bury the Maltese language in Australia, Malta Independent, 2 March 2010.

- ↑ Nigel Mifsud, Malta's Ambassador meets Maltese who have lived their whole life in Tunisia, TVM, 13 November 2017.

- ↑ Merritt Ruhlen. 1991. A Guide to the World's Languages, Volume 1: Classification. Stanford.

David Dalby. 2000. The Linguasphere Register of the World's Languages and Speech Communities. Linguasphere Observatory.

Gordon, Raymond G., Jr., ed. 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 15th ed. Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Alan S. Kaye & Judith Rosenhouse. 1997. "Arabic Dialects and Maltese", The Semitic Languages. Ed. Robert Hetzron. Routledge. Pages 263–311. - ↑ Borg (1997).

- ↑ Vella (2004), p. 263.

- ↑ "Punic language". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2013. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ Sheehan, Sean (12 January 2017). Malta. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761409939 . Retrieved 12 January 2017– via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Isserlin. Studies in Islamic History and Civilization. BRILL 1986, ISBN 965-264-014-X

- ↑ Hume (1996), p. 165.

- ↑ Borg (1997), p. 248.

- ↑ Borg (1997), pp. 249–250.

- ↑ Borg (1997), pp. 251–252.

- ↑ Borg (1997), p. 255.

- ↑ Borg (1997), p. 254.

- ↑ Borg (1997), p. 247.

- ↑ Borg (1997), p. 260.

- ↑ Puech, Gilbert (2017). The Languages of Malta Chapter 2: Loss of emphatic and guttural consonants: From medieval to contemporary Maltese. Language Science Press. ISBN 978-3-96110-070-5.

- ↑ Auroux, Sylvain (2000). History of the language sciences: an international handbook on the evolution of the study of language from the beginnings to the present. Berlin: New York : Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-011103-3.

- ↑ Mifsud, Manwel (1995). Loan Verbs in Maltese: A Descriptive and Comparative Study. Brill Publishers. p. 31. ISBN 978-90-04-10091-6.

- ↑ "Missierna : Malta". www.wordproject.org. Retrieved 2023-08-25.

- ↑ "Arabic Prayer-The Lord's Prayer". www.lords-prayer-words.com. Retrieved 2023-08-25.

- ↑ "The Lord's Prayer". syriacorthodoxresources.org. Retrieved 2023-08-25.

- ↑ Friggieri (1994), p. 59.

- ↑ About Malta [ permanent dead link ]; GTS; retrieved on 2008-02-24

- 1 2 3 Kossmann 2013, p. 75.

- 1 2 Kossmann 2013, p. 76.

- ↑ Żammit (2000), pp. 241–245.

- ↑ Compare with approx. 25–33% of Old English or Germanic words in Modern English.

- ↑ Kaye, Alan S.; Rosenhouse, Judith (1997). "Arabic Dialects and Maltese". In Hetzron, Robert (ed.). The Semitic Languages. Routledge. pp. 263–311.

- ↑ Hull, Geoffrey (2019). "Exploring the Berber element in Maltese".

- ↑ "Learn Maltese with uTalk". utalk.com. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ↑ "Teach Yourself Maltese Joseph Aquilina".

- ↑ "Country report for MINERVA Plus in 2005". Multilingual issues in Malta. Archived from the original on 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ Camilleri, Ivan (May 16, 2011). "Maltese language hardly used on the internet". Times of Malta. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

Related Research Articles

Arabic is a Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The ISO assigns language codes to 32 varieties of Arabic, including its standard form of Literary Arabic, known as Modern Standard Arabic, which is derived from Classical Arabic. This distinction exists primarily among Western linguists; Arabic speakers themselves generally do not distinguish between Modern Standard Arabic and Classical Arabic, but rather refer to both as al-ʿarabiyyatu l-fuṣḥā or simply al-fuṣḥā (اَلْفُصْحَىٰ).

Italian is a Romance language of the Indo-European language family that evolved from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire. Italian is the least divergent Romance language from Latin, together with Sardinian. Spoken by about 85 million people including 67 million native speakers (2024), Italian is an official language in Italy, San Marino, and Switzerland, and is the primary language of Vatican City. It has official minority status in Croatia and in some areas of Slovenian Istria.

Interlingua is an international auxiliary language (IAL) developed between 1937 and 1951 by the American International Auxiliary Language Association (IALA). It is a constructed language of the "naturalistic" variety, whose vocabulary, grammar, and other characteristics are derived from natural languages. Interlingua literature maintains that (written) Interlingua is comprehensible to the hundreds of millions of people who speak Romance languages, though it is actively spoken by only a few hundred.

The Romance languages, also known as the Latin or Neo-Latin languages, are the languages that are directly descended from Vulgar Latin. They are the only extant subgroup of the Italic branch of the Indo-European language family.

Sicilian is a Romance language that is spoken on the island of Sicily and its satellite islands. It belongs to the broader Extreme Southern Italian language group.

The Maltese alphabet is based on the Latin alphabet with the addition of some letters with diacritic marks and digraphs. It is used to write the Maltese language, which evolved from the otherwise extinct Siculo-Arabic dialect, as a result of 800 years of independent development. It contains 30 letters: 24 consonants and 6 vowels.

Maghrebi Arabic is a vernacular Arabic dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Libyan, Hassaniya and Saharan Arabic dialects. It is known as ad-Dārija. This serves to differentiate the spoken vernacular from Literary Arabic. Maghrebi Arabic has a predominantly Semitic and Arabic vocabulary, although it contains a few Berber loanwords which represent 2–3% of the vocabulary of Libyan Arabic, 8–9% of Algerian and Tunisian Arabic, and 10–15% of Moroccan Arabic. Maghrebi Arabic was formerly spoken in Al-Andalus and Sicily until the 17th and 13th centuries, respectively, in the extinct forms of Andalusi Arabic and Siculo-Arabic. The Maltese language is believed to have its source in a language spoken in Muslim Sicily that ultimately originates from Tunisia, as it contains some typical Maghrebi Arabic areal characteristics.

Neapolitan is a Romance language of the Italo-Romance group spoken in Naples and most of continental Southern Italy. It is named after the Kingdom of Naples, which once covered most of the area, since the city of Naples was its capital. On 14 October 2008, a law by the Region of Campania stated that Neapolitan was to be protected.

Regional Italian is any regional variety of the Italian language.

Tunisian Arabic, or simply Tunisian, is a variety of Arabic spoken in Tunisia. It is known among its 12 million speakers as Tūnsi, "Tunisian" or Derja to distinguish it from Modern Standard Arabic, the official language of Tunisia. Tunisian Arabic is mostly similar to eastern Algerian Arabic and western Libyan Arabic.

In linguistics, prothesis, or less commonly prosthesis is the addition of a sound or syllable at the beginning of a word without changing the word's meaning or the rest of its structure. A vowel or consonant added by prothesis is called prothetic or less commonly prosthetic.

Libyan Arabic, also called Sulaimitian Arabic by scholars, is a variety of Arabic spoken in Libya, and neighboring countries. It can be divided into two major dialect areas; the eastern centred in Benghazi and Bayda, and the western centred in Tripoli and Misrata. The Eastern variety extends beyond the borders to the east and share the same dialect with far Western Egypt, Western Egyptian Bedawi Arabic, with between 90,000 and 474,000 speakers in Egypt. A distinctive southern variety, centered on Sabha, also exists and is more akin to the western variety. Another Southern dialect is also shared along the borders with Niger with 12,900 speakers in Niger as of 2021.

The Maltese people are an ethnic group native to Malta who speak Maltese, a Semitic language and share a common culture and Maltese history. Malta, an island country in the Mediterranean Sea, is an archipelago that also includes an island of the same name together with the islands of Gozo and Comino ; people of Gozo, Gozitans are considered a subgroup of the Maltese.

Arbëresh is the variety of Albanian spoken by the Arbëreshë people of Italy. It is derived from the Albanian Tosk spoken in Albania, in Epirus. A related language is spoken by the Arvanites, with endonym Arvanitika.

Maltenglish, also known as Manglish, Minglish, Maltese English, Pepè or Maltingliż refers to the phenomenon of code-switching between Maltese, a Semitic language derived from late medieval Sicilian Arabic with Romance superstrata, and English, an Indo-European Germanic language with Romance superstrata.

African Romance or African Latin is an extinct Romance language that was spoken in the various provinces of Roman Africa by the African Romans under the later Roman Empire and its various post-Roman successor states in the region, including the Vandal Kingdom, the Byzantine-administered Exarchate of Africa and the Berber Mauro-Roman Kingdom. African Romance is poorly attested as it was mainly a spoken, vernacular language. There is little doubt, however, that by the early 3rd century AD, some native provincial variety of Latin was fully established in Africa.

Siculo-Arabic or Sicilian Arabic is the term used for varieties of Arabic that were spoken in the Emirate of Sicily from the 9th century, persisting under the subsequent Norman rule until the 13th century. It was derived from Arabic following the Abbasid conquest of Sicily in the 9th century and gradually marginalized following the Norman conquest in the 11th century.

Varieties of Arabic are the linguistic systems that Arabic speakers speak natively. Arabic is a Semitic language within the Afroasiatic family that originated in the Arabian Peninsula. There are considerable variations from region to region, with degrees of mutual intelligibility that are often related to geographical distance and some that are mutually unintelligible. Many aspects of the variability attested to in these modern variants can be found in the ancient Arabic dialects in the peninsula. Likewise, many of the features that characterize the various modern variants can be attributed to the original settler dialects as well as local native languages and dialects. Some organizations, such as SIL International, consider these approximately 30 different varieties to be separate languages, while others, such as the Library of Congress, consider them all to be dialects of Arabic.

Of the languages of Tunisia, Arabic is the sole official language according to the Tunisian Constitution.

This article is about the phonology of Egyptian Arabic, also known as Cairene Arabic or Masri. It deals with the phonology and phonetics of Egyptian Arabic as well as the phonological development of child native speakers of the dialect. To varying degrees, it affects the pronunciation of Literary Arabic by native Egyptian Arabic speakers, as is the case for speakers of all other varieties of Arabic.

References

- Aquilina, Joseph (1965). Teach Yourself Maltese. English University Press.

- Azzopardi, C. (2007). Gwida għall-Ortografija. Malta: Klabb Kotba Maltin.

- Borg, Alexander (1997). "Maltese Phonology". In Kaye, Alan S. (ed.). Phonologies of Asia and Africa. Vol. 1. Eisenbrauns. pp. 245–285. ISBN 9781575060194.

- Borg, Albert J.; Azzopardi-Alexander, Marie (1997). Maltese. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-02243-9.

- Brincat, Joseph M. (2005). "Maltese – an unusual formula". MED Magazine (27). Archived from the original on 5 September 2005. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- Bugeja, Kaptan Pawlu, Kelmet il-Malti (Maltese—English, English—Maltese Dictionary). Associated News Group, Floriana. 1999.

- Friggieri, Oliver (1994). "Main Trends in the History of Maltese Literature". Neohelicon . 21 (2): 59–69. doi:10.1007/BF02093244. S2CID 144795860.

- Hume, Elizabeth (1996). "Coronal Consonant, Front Vowel Parallels in Maltese". Natural Language & Linguistic Theory . 14 (1): 163–203. doi:10.1007/bf00133405. S2CID 170703136.

- Kossmann, Maarten (2013). The Arabic Influence on Northern Berber. Brill. ISBN 9789004253094.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Mifsud, M.; A. J. Borg (1997). Fuq l-għatba tal-Malti. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Vassalli, Michelantonio (1827). Grammatica della lingua Maltese. Stampata per l'autore.

- Vella, Alexandra (2004). "Language contact and Maltese intonation: Some parallels with other language varieties". In Kurt Braunmüller and Gisella Ferraresi (ed.). Aspects of Multilingualism in European Language History. Hamburg Studies on Multiculturalism. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 263. ISBN 978-90-272-1922-0.

- Żammit, Martin (2000). "Arabic and Maltese Cognate Roots". In Mifsud, Manwel (ed.). Proceedings of the Third International Conference of Aida. Malta: Association Internationale de Dialectologie Arabe. pp. 241–245. ISBN 978-99932-0-044-4.

Further reading

- (it) Giovan Pietro Francesco Agius de Soldanis, Della lingua punica presentemente usata da maltesi , per Generoso Salomoni alla Piazza di S. Ignazio. Si vendono in Malta, 1750

- (it) Antonio Emanuele Caruana, Sull'origine della Lingua Maltese , Malta, Tipografia C. Busuttil, 1896

- (it) Giovanni Battista Falzon, Dizionario Maltese-Italiano-Inglese , G. Muscat, 1845 (1 ed.), 1882 (2 ed.)

- (it) Giuseppe Nicola Letard, Nuova guida alla conversazione italiana, inglese e maltese ad uso delle scuole , Malta, 1866–75

- (it) Fortunato Panzavecchia, Grammatica della Lingua Maltese , M. Weiss, Malta, 1845

- (it) Michele Antonio Vassalli, Grammatica della lingua Maltese , 2 ed., Malta, 1827

- (it) Michele Antonio Vassalli, Lexicon Melitense-Latino-Italum , Roma, Fulgonius, 1796

- (it) Francesco Vella, Osservazioni sull'alfabeto maltese , 1840

- (it) Francesca Morando, Il-lingwa Maltija. Origine, storia, comparazione linguistica e aspetti morfologici, Prefazione di Joseph M. Brincat, Palermo, Edizioni La Zisa, 2017, ISBN 978-88-9911-339-1

- (en) S. Mamo, English-Maltese Dictionary , Malta, A. Aquilina, 1885

- (en) A Short Grammar of the Maltese Language , Malta, 1845

- (en) C. F. Schlienz, Views on the Improvement of the Maltese Language , Malta, 1838

- (en) Francesco Vella, Maltese Grammar for the Use of the English , Glaucus Masi, Leghorn, 1831

- (en) Francesco Vella, Dizionario portatile delle lingue Maltese Italiana, Inglese. pt. 1 , Livorno, 1843

- (en) Joseph Aquilina, Teach Yourself Maltese, English University Press, 1965

- (en) Geoffrey Hull, The Malta Language Question: A Case Study in Cultural Imperialism, Said International, Valletta, 1993

- (mt) Vicenzo Busuttil, Diziunariu mill Inglis ghall Malti , 2 parts, N. C. Cortis & Sons, Malta, 1900

External links

-

Maltese travel guide from Wikivoyage

Maltese travel guide from Wikivoyage - Maltese languages and literatures collection of L-Università ta' Malta

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.