Introduction

The Northern League, now known just as the League, is currently Italy’s largest right-wing party as well as the oldest party in Italy. While the League may be old, it was long a regionalist movement and only recently has turned its focus onto national affairs and seen significant growth as a result. The new League, focused on nationalism rather than regionalism is built on the idea of “Italy First” and has embraced an anti-European Union agenda. The party previously did not hold very much power in government. This changed, however, in the 2018 elections. The League itself picked up 17.4% of the vote and the center-right coalition led by the League and Matteo Salvini was the most successful alliance in the elections. The coalition won 265 seats in the lower house (the Chamber of Deputies) and 137 seats in the Senate. While not enough for a majority alone, in coalition with the Movimento 5 Stelle (5 Star Movement or M5S), the right-wing coalition and the League have a majority in both chambers. The election made the League’s party leader, Matteo Salvini, the Deputy Prime Minister.

https://ednh.news/populist-surge-leaves-italy-in-political-limbo/

The success of the League in the most recent Italian elections is notable not just in the success of right-wing politics but also in the successful shift of the League’s regional politics. The Northern League under Umberto Bossi, during the 1990s and early 2000s, was a strictly regional party, arguing for autonomy of northern provinces. The original Northern League villainized Rome as a totalitarian government taking from the successful north and giving to the less successful southerners. The new League, led by Salvini starting in 2013, has largely abandoned these ideas, instead villainizing the EU. As a result, a party that has long described southern Italians as inferior, won a significant number of votes from central and southern Italians. The League won 13.4% of the votes in Lazio as compared to the 0.2% won in 2013 and even in Sicily the party won 5.2% of the vote (again up from 0.2% in 2013). These gains in the south and the general success of the League in the 2018 elections represent a rebranding of the League that successfully appeals to a larger demographic of Italians.

The Old Lega Nord

The Northern League was officially formed between 1989 and 1991 when Umberto Bossi, leader of the Lombard League, formed an alliance with 5 other northern leagues. Each of the original Leagues was also a regional league concerned with their own autonomy. In the combination of these Leagues and the formation of the Northern League, the regionalism turned into a call for a new independent state, Padania. In this early state, the Northern League was largely just the party of Umberto Bossi. What Bossi said was what the party stood for and what they wanted. As a result, the Northern League has held many different ideas and agendas and very seldomly has an officially-stated party platform. This has carried over into the League as well. From its beginning, the Northern League has been more an opposition party than a ruling party. The growth of the League grew out of a rising resentment of the corruption in government and the disintegration of the Christian Democrats and the Socialists (previously the two main parties). The Northern League was committed to institutional reform. They sought to create a fresh start for Italy and weed out the corruption and incompetence. To Bossi though, the corruption was a symptom of the south and Roman bureaucracy, and the new Italy should be built on the industrial success of the north.

Throughout the 90s Bossi (any by extension the Northern League) oscillated between calls for northern independence and Italian nationalism. While the public statements of the party were not always straightforward, the sentiment was. All of the original leagues that formed the Northern League were founded as ethnic movements and purported some sort of superiority over southern Italians. Once banded together, this idea remained strong. The party depicted southerners and inferior and often accused Rome of being systematically biased against the north. Much of the speech and advertising for the party depicted northerners as hard working, wealthy people whose hard-earned money was being passed by Rome to the lazy, undeserving southerners. The Italian south was often seen as barely Italian as witnessed in Bossi’s famous (and racist), “Africa Begins at Rome”. With the south established as a region of inferior people, the Northern League was able to address the south as a problem plaguing Italy, and to propose the question of what to do. The original answer within the party was separatism. These barely Italian southerners shouldn’t be a part of Italy, they believed. Even in more nationalist approaches to the problem of the south, the Northern League maintained that a unified Italy should better serve the north and be run by northerners.

As a result of these core beliefs and the concentration of the League in northern Italy, there was little to no support for the party in central or southern Italy. Naturally, many of the members of the former northern leagues that came together remained supporters of the Northern League. As the Northern League grew however, their support no longer came just from small pockets of northerners who believed in some wort of cultural or ethnic superiority over southerners. The party was very popular among young men, partly for their traditional and masculine approach to home and work life, but also because many of these young men were enjoying the benefits of industrialization. Between 1987 and 1992 the League saw its biggest growth in areas with strong industrial growth. As incomes increased and the north experienced economic growth, the idea that the south was somehow benefitting unfairly from their success gained traction. This economic growth and the north-first ideals of the party allowed it to grow and maintain a presence in northern politics over the following decade.

http://www.leganord.org

The New Lega

While the League had occasionally and slowly adopted more nationalist ideas in the 1990s and 2000s, the shift in messaging was not fully realized until 2013 when Mattea Salvini took over as the head of the Northern League. The Northern League was often synonymous with Umberto Bossi; you couldn’t have one without the other. Bossi himself once said, “I am the League”. This did not hold true, however, as the party entered the 2010s. Involved in a fraud scandal, Bossi was forced to resign as the party’s leader in April of 2012. The following year, Matteo Salvini was elected leader of the party and maintained his leadership in the following 2017 election. In the 8 years since Salvini took over, the League has seen some significant changes.

The most obvious of such changes is the new name of the party. While still officially the “Lega Nord”, the party now goes by the “Lega”, or the League. The dropping of the “Nord’ in their title reflects some large underlying changes within the party, namely the shift in their north-first policy and the consequences that came with it. The League, as a result of its history and the lack of southern Italians in its leadership, still is and may always be more successful in the north. The results of the 2018 election show, however, that the party now speaks for more than just northerners.

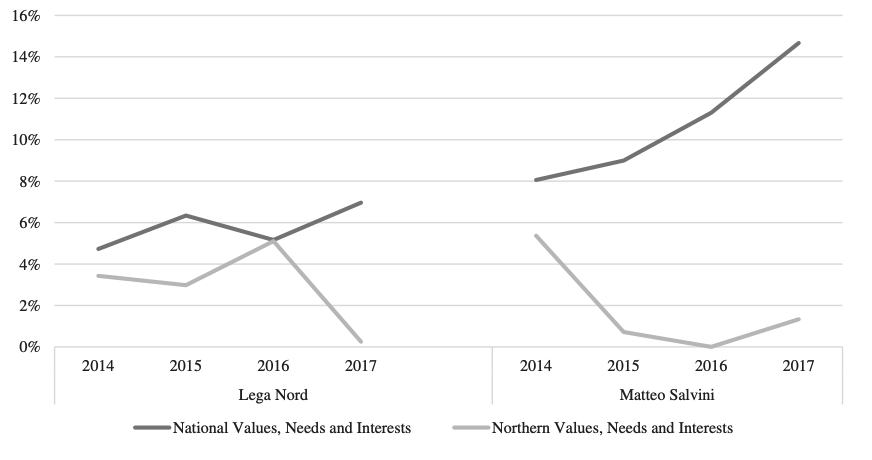

Early in his leadership, Salvini apologized to southerners regarding anti-south statements that he had previously made throughout his career. He espoused this new (for the League) idea that Italy must save itself as a nation, else each individual region will fail as well. His thinking here is that even an independent Padania would still be the victim of a totalitarian European Union. True to the oppositionist origins of the party, Salvini describes the EU as the seat of real power and the home of the corruption that is dragging Italy down. This idea is reflected in the shift in messaging by both the Lega Nord and Matteo Salvini. Across social media and official websites, the discussion of Northern culture and values and has been replaced by the discussion of national culture and values. As the 2018 elections approached, the party made some big changes. Salvini created movements allied with the League, including ‘Noi con Salvini’ (Us with Salvini), and for the first time ran candidates in some local elections in central and southern Italy. Prior to the election, these movements merged with the League, and Salvini’s more nationalist approach appeared to pay off. As mentioned earlier and seen in the tables and graphics above, the League led center-right coalition made large gains in southern and central regions. For the first time, the League had some serious governing power and had appealed to Italians as a whole.

While the shift from regionalism may seem like a large change in the politics of the League, under the surface much is the same. They remain a populist opposition party with traditional conservative views and hold the right-wing idea that Italy is in trouble and needs saving or a fresh start. The party under Bossi put much of the blame in the national government, based in Rome. They believed that the southerners were inferior and ruining Italy. The corrupt southerners in Rome were supposed to have been preventing the north from achieving its true potential. Obviously, this idea of Rome as the enemy has subsided, but the underlying idea remains. Salvini, rather than seeing Rome as ruining the north, sees the European Union as ruing Italy. Similarly, it is no longer the southerners that are inferior and ruining the country, but the immigrants. The messaging leading up to the 2018 election painted the left-wing parties as too sympathetic to the EU and leaned on issues like immigration and terrorism more than they had before. The money that hard-working Italians are making is purportedly being given to undeserving immigrants, instead of southerners. The core belief is almost exactly the same, Italy is a victim of a centralized power enacting unfair policies, and to move forward true citizens must be put first.

http://www.leganordpiemonte.org

Conclusion

The League is now bigger than ever, and its move to finally include southern Italians may at first seem positive. It is obviously nice to see the longstanding north-south divide subside and to see a party originally run by Separatists, advocating for a unified Italy. Much of the biased, damaging, and occasionally bigoted rhetoric used by the Northern League against the south in the 1990s and 2000s is being abandoned. As a result, the League has seen large growth and now holds more governing power than ever before. While the League may look quite different now under Salvini, it is however, still very much the right-wing party that it started as. The conservative traditional values remain the same, and what was once a blend of regionalism and nationalism is now outright nationalism. In changing their tune on Rome and southerners the party has instead set their sights on the EU and immigrants and have done so with an “Italy First” slogan that mimics the growth of other right-wing movements across the world. In their rebranding to the ‘League’, the Northern League has opened its doors to many more Italians, and in doing so they have helped to spread right-wing nationalism further across the country.

References

Adler, Lucy. “Populist Surge Leaves Italy in Political Limbo.” European Data News Hub, Agence France-Presse, 24 Oct. 2018, ednh.news/populist-surge-leaves-italy-in-political-limbo/.

Agnew, John. “The Rhetoric of Regionalism: The Northern League in Italian Politics, 1983-94.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 20, no. 2, 1995, pp. 156–172. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/622429. Accessed 6 Apr. 2021.

Agnew, John, and Carlo Brusa. “New rules for national identity? The Northern League and political identity in contemporary northern Italy.” National identities 1.2 (1999): 117-133.

Albertazzi, Daniele, Arianna Giovannini, and Antonella Seddone. “‘No regionalism please, we are Leghisti!’The transformation of the Italian Lega Nord under the leadership of Matteo Salvini.” Regional & Federal Studies 28.5 (2018): 645-671.

Anna Cento Bull (2009) Lega Nord: A Case of Simulative Politics?, South European Society and Politics, 14:2, 129-146, DOI: 10.1080/13608740903037786

Bremmer, Ian. “What to Know About Italy’s Populist Coalition Government.” Time, Time, 18 May 2018, time.com/5280993/m5s-lega-italy-populist-coalition/.

George Newth (2019) The roots of the Lega Nord’s populist regionalism, Patterns of Prejudice, 53:4, 384-406, DOI: 10.1080/0031322X.2019.1615784

D’Alimonte, Roberto. “How the Populists Won in Italy.” Journal of Democracy, vol. 30 no. 1, 2019, p. 114-127. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/jod.2019.0009.

Vampa, Davide. ” Matteo Salvini’s Northern League in 2016″. Italian Politics 32.1: 32-50. < https://doi.org/10.3167/ip.2017.320104>. Web. 28 Apr. 2021.