Lady Mary sinking: boaters should take heed

The March 2009 sinking of the fishing vessel Lady Mary off Cape May, N.J., with the loss of six crewmembers inspired a 20-page Pulitzer Prize-winning newspaper account of the tragedy and, with the loss of five other fishermen off New Jersey in 2009, raised an alarm that helped push far-reaching fishing vessel safety measures through Congress.

Yet the cause of the Lady Mary sinking remains in dispute. A May 2 report from the National Transportation Safety Board blames the loss on water flooding in through an open hatch in rough seas. Others still believe the evidence points to a collision, probably with a container ship running through scalloping grounds that night.

In either case, the sinking raises a red flag for pleasure boaters, who also risk collision with big ships in busy sea lanes, especially at night or in fog or rain, and loss of their vessels from water flooding through an open hatch or a hull breach.

The National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety estimates that an average of 50 commercial fishermen died on the job each year from 2000 to 2009 in the United States. A little more than half of those deaths occurred after abandoning ship during a catastrophic event, such as a sinking, capsize or fire.

The loss of 11 fishermen in waters off New Jersey was the worst record of commercial fishing deaths in that state since 1921. That and Pulitzer-caliber reporting by the Newark-based Star-Ledger helped build momentum for the new safety requirements. They are the first major fishing-safety reforms since the Commercial Fishing Industry Vessel Safety Act of 1988.

“It’s a big step forward,” says Jack A. Kemerer, chief of the Coast Guard’s fishing vessel activities division. He says a high-profile case such as the Lady Mary can draw attention to legislative initiatives that might otherwise languish.

The 1988 act focused on safety gear to help crewmembers survive catastrophes. The 2010 legislation focuses on uniform safety standards, vessel examinations every two years, captains’ training, and designing and building boats to classification standards — measures that aim to prevent catastrophes, Kemerer says.

The Lady Mary sinking also uncovered shortcomings in the administration and use of EPIRBs. The unique 15-digit identification code for the Lady Mary’s beacon was incorrectly recorded in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s database. When the EPIRB activated and sent its alert signal to a NOAA computer via satellite, the computer couldn’t find the identifier code and classified the beacon as “unregistered.” That prevented rescue coordinators from identifying the vessel.

Also, the Lady Mary’s EPIRB wasn’t equipped with GPS, so rescue coordinators could not get the vessel’s position as soon as the EPIRB activated. It wasn’t until an hour and 35 minutes after the EPIRB activated that coordinators were able to pinpoint its location, using information sent from two low Earth-orbiting satellites. Had the rescue helicopter launched an hour and 35 minutes earlier, two of the crewmembers who were found dead in their immersion suits early in the search might have survived, the NTSB report says.

Knowing the code

In the months after the sinking, NOAA embarked on a campaign to contact its 235,000 registered beacon owners and advise them to check the information about their EPIRBs in NOAA’s database, including the identifier code, to be sure it is correct. The NTSB also issued a recommendation to the Federal Communications Commission to require all EPIRBs on commercial vessels to have the capability of transmitting position data, a measure that has yet to be adopted.

New Jersey-based fishing crews suffered more than their share of tragedy in 2009. Alisha Marie, a 38-foot scalloper based in Point Pleasant, took a wave, capsized and sank 26 miles off Barnegat Inlet in 6-foot seas and 30-mph winds. Two fishermen died and a third was rescued from a raft after that Dec. 23 sinking.

The 44-foot Sea Tractor, based in Cape May, sank Nov. 11, 20 miles east of Cape May in winds and seas from Tropical Storm Ida. All three of its crewmembers were lost. But it was the compelling story of the Lady Mary sinking, its effect on the North Carolina fishing family who owned her, and their efforts to come to grips with why it sank that provided grist for both the Pulitzer story, written by Amy Ellis Nutt, and the new fishing vessel safety requirements.

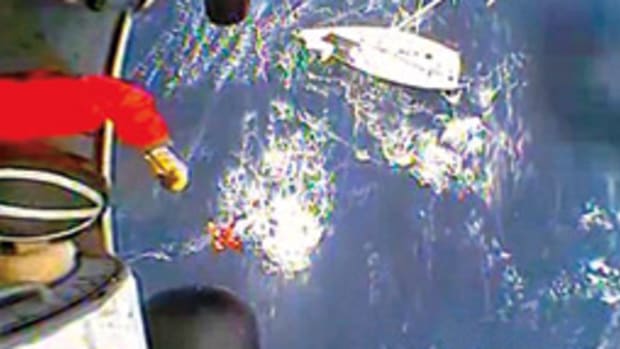

Smith family patriarch Royal “Fuzzy” Smith Sr. of Bayboro, N.C. — shoreside manager for the Smith & Smith fishing business, owner of the 72-foot Lady Mary — lost two sons, a brother and a cousin when the vessel sank March 24 in the Elephant Trunk, a productive shellfish area 65 miles off Cape May. In April 2009, the Coast Guard convened nine days of hearings about the sinking. It still has not released its conclusions but seemed at the time to be leaning toward a finding of inherent vessel instability, a malfunction of the dredge or circumstances that might have caused the vessel to list severely in the seas, take on water and sink.

The family contended that damage to the rudder, props, stern ramp and gallis, and red paint on the trailing edge of the rudder indicate the Lady Mary had sunk in a collision, a theory Nutt’s story supports. It cited a number of experts who thought the vessel had been run down and only one forensics team that didn’t.

The NTSB finding states that the Lady Mary, buffeted by 7-foot waves and 35-knot winds, began taking on water over the sides and across the deck, and that water flooded into the lazarette through a hatch that had been left open to pump water out. Its engine and electrical system disabled by the flooding, the Lady Mary began to drift.

“The water accumulating in the lazarette would have sunk the vessel’s stern deeper into the sea, allowing even more water onto the deck and into the lazarette” until the boat sank, the report says.

The family’s doubts

That finding remains in dispute. Besides the expert opinion in the Star-Ledger story, Stevenson Weeks, the Smith family’s Beaufort, N.C., admiralty lawyer, remains steadfast in his belief that the Lady Mary sank in a collision. He believes the Coast Guard convened its hearing prematurely, before divers had even examined the Lady Mary wreckage, because they had already made up their minds that this was a classic case of vessel instability.

The Lady Mary had been altered since its construction in 1969 from a shrimp boat to a scallop dredge with the addition of a scallop-shucking house, a bunkroom and galley, and on top of that a wheelhouse and winch deck — all built of plywood. To compensate for the greater weight topside, a fuel tank under the hold was filled with concrete.

Weeks believes the Coast Guard saw the Lady Mary as the poster child for advocating better design and construction standards for fishing vessels. “In my opinion, they developed this theory to substantiate [the need for better regulation of vessel stability] and to bolster their position in Congress,” he says.

He says the damage to the stern was too great to have been the result of the vessel falling 210 feet through the water column and hitting bottom. “We still believe this was a result of vessel collision,” he says.

Whatever the cause of the Lady Mary sinking, the upshot is that Congress has adopted a host of new and uniform safety standards for all fishing vessels — documented and state-registered — operating beyond three nautical miles of a fixed baseline. Among those standards:

• The vessels must carry a survival craft of some kind and be examined at the dock at least once every two years.

• Masters must keep a logbook of equipment maintenance, crew drills and instruction, and receive training in seamanship, navigation, stability, firefighting, damage control, safety and survival, and emergency drills.

• New vessels under 50 feet must meet federal recreational boat standards, which include requirements for electrical and fuel systems, ventilation below deck, load capacity, flotation (for boats less than 20 feet), navigation lights, and horns, bells and whistles.

• New builds 79 feet or larger must have the loadline marked on the hull.

• All fishing vessels over 50 feet operating beyond 3 nautical miles must be designed and built to one of the classification standards.

The legislation, which will be translated into regulations in the next several years, covers 20,000 federally documented and 58,000 state-registered vessels.

Meanwhile, Weeks says his and the Smith family’s concerns about the NTSB findings likely will remain just that — concerns. “My client has limited assets to chase this rabbit,” he says.

It could cost $1 million to raise the Lady Mary, do a thorough investigation of other vessels in the vicinity of the sinking that night, and challenge the NTSB’s findings. That’s $1 million the Smiths don’t have.

“I don’t think we’re ever going to get an answer to this mystery unless down the road someone admits [there was a collision], and that’s very unlikely,” he says.

Amy Ellis Nutt’s Pulitzer Prize-winning story on the Lady Mary from the Star-Ledger can be read at www.pulitzer.org. Click on “2011” and then on “Feature Writing.”

See related article:

- Yet another collision where fishing vessels work

This article originally appeared in the August 2011 issue.