One fine morning in late spring I find myself wandering around a castle. This particular castle used to be the home of one of the most extraordinary private collections of art in England, and though its treasures – the Cézannes, the Renoirs, the Turners – are now long gone, a few in the care of public galleries, still others sold to the only collectors rich enough to be able to afford them, it remains a wonderful place to be. Here, any dusty postcard might bear the signature of Edith Wharton, any family photograph could turn out to be the handiwork of Man Ray.

This is Saltwood Castle in Kent, which began its life as an Anglo-Saxon stronghold and was later the residence of the archbishops of Canterbury (by tradition, it was from Saltwood that four knights set out to murder Thomas Becket in 1170). The story goes that during the war Göring ordered the Luftwaffe not to bomb nearby Hythe because he had identified Saltwood as his post-invasion home, and should you be lucky enough to visit (it is not open to the public) it's easy to see why (the art, I should add, had yet to arrive when the founder of the Gestapo saw it). With its ragstone walls, forbidding towers and pea-green moat, it seems to have come straight out of a fairytale: remote, romantic, impervious to the passing of the centuries.

Kenneth Clark, the curator, scholar and presenter of the landmark 1969 BBC series Civilisation, bought Saltwood in 1953, and lived here until his death in 1983, filling it with beautiful things all the while (though he spent his last years in a house in the grounds, having made way in the castle for his elder son, Alan, the Conservative MP). For him, too, it was love at first sight. After his marriage in 1928, Clark – always known as "K" – and his wife, Jane, one of the great hostesses of her day, had lived in a "fidgety" number of houses; they were forever moving, never quite content. Saltwood, though, put an end to this. Clark made its owner an offer before he'd even stepped inside. His friends thought his new toy "absurd", "pretentious", "all stairs" and – the worst insult of all – "gothic revival". But Clark was besotted. When he and Jane moved in, they couldn't bear to recoup their costs by selling even one of its better tapestries: "We were reluctant to break this dream that had taken so strong a hold on us."

Today, another Jane lives in the house: the long-suffering widow of the late Alan Clark. This Jane is not a great one for receiving visitors, but I have travelled here with Chris Stephens, the curator of Tate Britain's forthcoming exhibition about Kenneth Clark, of whom she is clearly fond (Stephens has been up and down to Kent a lot lately, in search of photographs, newspaper cuttings and other bits and pieces that will work in the context of the show), and she has even made shortbread to welcome us. What does she think her father-in-law would have made of the Tate show? "I don't know," she says, pouring the coffee. "But I am thrilled. I can't wait to see everything in its place. It's going to be wonderful."

Jane was, as she puts it, "notoriously young" when she met her father-in-law for the first time (she married Alan in 1958, when he was 30 and she just 16). Was he a terrifying prospect? "You were slightly in awe of that generation. I was a bit frightened, but he was nice, too. Of the two of them, it was my mother-in-law who was the more forbidding. She had moved up in the world, you see, and she was really called Betty, not Jane. When a relation came over from New Zealand and kept calling her Auntie Betty, I could see her getting crosser and crosser. So then my father-in-law said teasingly: 'Would Auntie Betty like some more wine?' I thought she was going to explode!"

Jane loves Saltwood, her home for more than 40 years, and perhaps she transmitted this to her father-in-law, for he left her a beloved dinner service in his will. "It's not actually very big," she says, nodding at the battlements from the window. "It's a pile of rubble, half of it." As for the collection it once housed, she is apt not to make too much of that. "Celly [Alan's younger sister] is adamant that Papa [K] wasn't really a proper collector. It was more a case of: you saw a beautiful piece, you wanted it. He always said things should be used. A Duncan Grant rug was to be kept on the floor, not the wall. It wasn't a snobbish thing at all. He liked things you wouldn't find in a millionaire's apartment in Manhattan, but which you might just find in a stationmaster's house in Shropshire. There were copies of things, and broken things, too." For Clark, the cost of something was unimportant. What mattered was that it was loved.

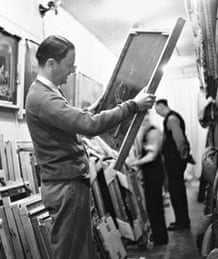

Easy for him to say! Clark's collecting began at a time when it was still possible to pick up great art for a relative song. In the 1930s, for instance, he bought a portfolio of Cézanne drawings from the artist's son while en route from one Paris station to another (the less important of these, he later gave away to friends). The Tate show will include some 230 works, most of which once belonged to Clark – the rest will be work he commissioned or acquired during his tenure as the director of the National Gallery – and as a result, its sweep will be extraordinary. It will begin with the Aubrey Beardsley drawings he loved as boy, move through the Italian art on which he worked after Oxford, and thence to his lifelong passions: not only Renoir and the other impressionists, but also various textiles, china, and medieval illuminations; work by Constable, Turner (who painted Saltwood in 1795) and Samuel Palmer; by his friends Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant; and, perhaps most significant of all, by the English artists he supported in the 40s and 50s, among them John Piper, Victor Pasmore, Graham Sutherland and Henry Moore. "Clark was worried by the lack of patronage in the 20th century," says Stephens. "The church and the aristocracy weren't doing it any more, and the middle classes hadn't yet, he felt, taken up their responsibilities. He believed contemporary art needed to be encouraged, and he almost single-handedly took that on, lending artists money, guaranteeing their mortgages, paying them salaries."

The Tate's show, Stephens tells me as we walk the castle's gloomy corridors, began its life as an exhibition about this patronage. But he soon realised he would have to widen its scope to include Clark's role as a communicator, a function he fulfilled chiefly through television – for it's this that connects him to our own age. The shift turned out to be fortuitous. The BBC's director general, Tony Hall, is committed to remaking Clark's landmark series Civilisation and the exhibition now happily coincides with the ongoing debate about who will present it – and, more widely, with the issue of whether such a project could ever be successful. "Suddenly, people are curious about Clark again," says Stephens. "Who was he? Why did he matter? And why should we care about him now?"

Clark was born in 1903, into a world of glittering privilege. His father, Kenneth M Clark, had inherited a fortune from interests in the family business – the Clark Thread Company of Paisley – and now belonged to the idle rich. (As his son commented, though there were many who were richer than his father, few could have been more idle.) The family's main home was the 50-bedroomed Sudbourne Hall in Suffolk, but there was also a Scottish estate on the Ardnamurchan peninsula, a London town house, several yachts for racing, and hotels in the south of France, one of which Clark would later receive from his father as a wedding present. A drinker and gambler who liked to frequent the casinos of Monte Carlo, Clark senior resolutely refused to moderate his behaviour in spite of the pursed disapproval of his wife, Alice, who had Quaker roots.

In his 1974 memoir, Another Part of the Wood, Clark, an only child, presents himself as a solitary boy left at the mercy of his parents' servants, who enacted on him what he calls "an unconscious programme of revenge" against their employers. In particular, they liked to feed him inedible food: "I remember a cheese so full of weevils that small pieces jumped about the plate; I remember branches of bitter rhubarb, sour milk, rancid butter – and, of course, nothing but obstinate silence." But apparently there were limits to this neglect. When his mother found him weeping in the nursery one day, she fired the German nanny who'd called him wicked, and replaced her with a Miss Lamont, aka Lam, whom he adored. Lam, he would write later, "saved my life".

Clark thought his parents' renovations of Sudbourne "in very bad taste". So where did his own famously good taste come from? In later life, he would present it as an innate thing, an extreme sensitivity to the visual which manifested itself almost before he went to school. But his father genuinely liked art – he owned work by Millais, Wilkie and Landseer – and was keen to encourage his son's interest. On Christmas Day in 1910, he presented the seven-year-old K with a book about the Louvre, a volume he came to love so much that at 70 he could still recite the names of the paintings he'd first seen among its pages. When K announced to the world, not too much later, that he wanted to be an artist like Charles Keene, whose illustrations he'd seen in Punch, his father appears to have been – initially at least – delighted. In 1910, Lam took K to see the Japanese exhibition at White City, where he found himself "promoted into a different world" by a pair of 16th-century painted screens. For his 12th birthday, then, his father he gave him an album of Japanese prints, among them several woodcuts by Hokusai. Perhaps most important of all, Clark senior commissioned a portrait of the nine-year-old K by Charles Sims. Watching Sims in his studio made a deep impression on his subject. This was the beginning of his abiding respect for the working artist.

After prep school, Clark was sent to Winchester, where he was beaten twice a week. "I lay low as much as I could," he told his biographer, Meryle Seacrest. He loved the lectures about Florentine art given by its head, Monty Rendall, and it was at Winchester that he discovered Ruskin. But his emotional life now took a turn for the worse: the atmosphere at school, the war between his parents at home; it was all too much. For the last three years of his schooling, he was convinced he was dying of paralysis ("pure neurasthenia, of course," he said later). His emotions were "frozen" and when he went up to Oxford – he hung a Corot on the wall of his room at Trinity College – he was not popular. "He was cocooned in a civilisation of his own up there," remarked one of his contemporaries. Clark was immaculately dressed and highly cultured, but he was also chilly and condescending.

Clark was studying history, but he could not leave art alone. The question was: how to make a living from it? In 1923, he was introduced to Roger Fry, the critic. Clark was already in thrall to Fry, having heard him lecture, but their friendship was sealed when he bought one of his "heavy, lifeless" paintings – "the way to Roger's heart". Through him Clark met other Bloomsburys such as Vanessa Bell, whom he would later commission to design a dinner service, but it was Fry who had the greatest impact. Here was a man who not only loved art, but who believed that everyone was capable of such a passion. Thanks to his post-impressionist exhibitions, moreover, he had done more than anyone to change taste in Britain.

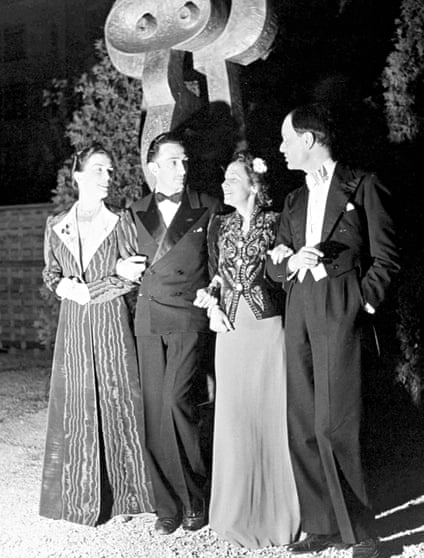

The years of what he would later call the "Great Clark Boom" were now about to begin. In 1925, he met Jane, a beauty who during her own time at Oxford had developed a reputation for originality thanks to the way she used curtain material and safety pins to construct her party dresses. They married in 1927, and went on to have three children: Alan, and the twins Colin and Colette. Jane, though, was always vastly more interested in her husband than in her offspring, and in due course her lavish entertaining and her style (she wore Schiaparelli, and held fashion shows to which both Queen Elizabeth, with whom her husband enjoyed a flirtation, and the young princesses were invited) made the young Clarks the most sought-after couple in London. Their social circle included Churchill, Chamberlain, Cecil Beaton, Noel Coward, Aldous Huxley, Edith Sitwell, HG Wells and William Walton, who later became Jane's lover. Meanwhile, Clark took up a job in Italy working for the critic Bernard Berenson, then the leading expert on Renaissance art, and began work on his first book, The Gothic Revival. In 1928, he was offered the job of cataloguing the Leonardo drawings in the Royal Collection at Windsor, a remarkable coup for a 25-year-old, and in 1931, he was made the keeper of the department of fine art at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. Two years later, aged just 31, he accepted the job of director of the National Gallery – though not without misgivings. As he wrote to his friend Edith Wharton, relinquishing "the vegetarianism of the vita contemplative" for a more "carnivorous diet" of decision-making felt all wrong. Scholarship was real work; by comparison, committees and meetings were a breeze.

It would be hard to overstate Clark's effect both on the National Gallery and on the public's affection for it, and this is a central theme in the Tate's show. "Everything he did anticipates the way we talk about museums now," says Chris Stephens. "Until his arrival, the big galleries were largely private domains, where curators did what they wanted. Clark, though, believed that its primary function should not be scholarship or conservation, but to feed the public imagination. He introduces electric lighting, so it can stay open after dusk; he opens it at weekends, and on Cup Final day. It's an extraordinary transition. In 1933, when he's appointed, the National Gallery feels irrelevant to most people. By 1943, it's a centre for national culture."

The real turning point, however, came with the war. Clark was determined that the gallery should remain open even once the blitz began – particularly once the blitz began – and put together a rolling programme of concerts and temporary exhibitions, many of which were organised by the War Artists' Advisory Committee he'd established in 1939. Its collection had been sent to Wales for safekeeping, but after 1943, when the bombing eased, it was decided that the odd painting could be returned to London, and thus the "Picture of the Month" began.

"Clark tried to put art into battle the same way that Churchill used the English language," says James Stourton, who is writing his authorised biography. "He believed you had to ask: what are we fighting for? What are our values? The art could be used [to boost] morale, to tell the story of the Britain we were trying to preserve. He made the National Gallery almost the emotional centre of resistance to Hitler, and for the first time in its history, it became popular. The Picture of the Month was talismanic."

Clark made some magnificent acquisitions for the National Gallery: works by Constable, Rembrandt, Ingres, Poussin. But after 1938, curating mattered to him less than this connection with the public, and he was committed to ensuring that the state continued to play an important role in the arts. When he resigned from the National Gallery, his next but one job was as chairman of the Arts Council.

How on earth did this stiff, patrician man move into television? In fact, Clark had always liked the idea of television; he believed that once the technology had improved, it would be a fine way of disseminating ideas. In 1954, he was one of the founders of the Independent Television Authority, serving as its chairman until 1957 (though this didn't go down well with some of his peers, who booed him at his club). It was Lew Grade at ATV (the London franchise) who spotted his potential as a presenter, and he went on to make some 50 documentaries for the company. Still, this did not make him a natural choice to present Civilisation when his contract with ITV ran out. David Attenborough, then running BBC2, suggested the idea to him in the summer of 1966 – the plan was to outline the history of western art, architecture and philosophy from the dark ages on – but when he met the series' director, Michael Gill, they took an instant dislike to each another. Gill didn't want more of Clark's pompous televised lectures, and snooty Clark didn't want to be told what to do.

In the end, though, Gill won the day, persuading Clark that if he would only write a series of essays, he would realise his ideas, however complex, and turn them into films. Together, they travelled some 80,000 miles, visited 11 countries, shot on 130 locations, spent £130,000 (then a record) and used enough feet of film to make six feature-length films. The response was extraordinary. The series was, JB Priestley wrote, "itself a contribution to civilisation". But it wasn't only the critics who swooned. The public was thrilled by it too: among the hundreds of letters Clark received were several from would-be suicides who wrote that he had given them a reason for going on (they made him weep).

Even now, says James Stourton, thousands of DVDs of the series are still sold every year: "It has never died. It's like being on a magic carpet. It's an amazing grand tour. Today, the presentation gets in the way a bit. He's wearing funny clothes, and has a funny voice. You have to get beyond the Burberry coats and the manner and listen to the words." Clark was by now beginning to fall out of sympathy with the art world; painting, he thought, had not been in such a bad state since the death of Giotto. But, no matter. Amazingly, it was for these films that he would be remembered, his passion for art and all its possibilities somehow having transmitted itself to a rapt nation. The clipped vowels and the awkward body language didn't bother the public (even in 1969 he would have sounded stiff, for this, after all, was the year Monty Python made their TV debut) because, as Stourton puts it, "he owned his material". At the Tate show, visitors will be able to see this ownership for themselves thanks to several carefully positioned screens – and some will doubtless ponder if any presenter now, relying as he or she inevitably will on a team of researchers, will ever be able to match its undoubted authority.

Civilisation's final pessimistic scene – Clark worries to camera about the future, and quotes gloomily from Yeats – was filmed in the library at Saltwood, and it's to this building that Stephens and I head before we return to London. It's cold, and the place smells of old paper and woodsmoke. Clark worked in a small room – a kind of cell – up a stone staircase just off it, and his desk has an expectant air, as if it were still awaiting his return (though, in fact, he wrote on his knee, like a boy writing a secret diary).

Snooping around in search of clues to the character of a man whom even Chris Stephens continues to find elusive – "I still have no sense at all of whether or not I would have liked him" – we find a letter from the Queen in which she thanks the Clarks for their wedding present, a flashy memento that seems at odds with the rows of leather-bound books. For a moment, I wonder if it was on display in his day, or whether its careful placing is the work of later hands. I can't match it with the man who, Jane insists, banned even the Saltwood archers from practising beneath his window lest they disturb his work. But then, how did that man tolerate the longueurs and compromises involved in television? Why was he so keen to emerge from behind these walls and talk to the world about art?

No one seems to know the answers to these questions. Clark was sealed off, a mystery, even to himself. "I have no aptitude for self-analysis," he writes in his memoirs. "When I try to examine my character, I soon give up in despair." Perhaps it was simply that it was better to look out than within, to see the barbarians at the gate not as the enemy, but as a helpful, even soothing distraction.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion