In 1854 Euphemia Ruskin went to court to annul her six-year marriage to John Ruskin on the grounds of non-consummation. In that explosive moment the relationship between the foremost public intellectual of the day and his pretty young wife became a cause célèbre. Contemporaries weighed in with faux concern about what exactly had gone on (or not) in the Ruskins' bed, while members of the opposing camps wrote wildly slanted accounts about who was really to blame. Books, plays and even a film followed down the decades, mostly casting Ruskin as creepy, controlling and eternally flaccid. Meanwhile, Effie Gray, pointedly restored to her maiden name, had emerged by the middle years of the 20th century as the historical pinup for hard-done-by women everywhere.

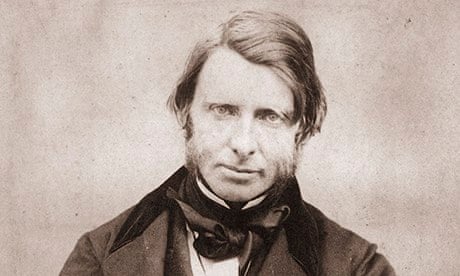

Now Robert Brownell wants to give the biographical pendulum a hefty shove in the opposite direction. In 600 closely wrought pages he argues that it was Ruskin, not Gray, who was tricked into a fraudulent marriage. What's more it was Ruskin and not Gray who manoeuvred the whole miserable business to its sensational close. In making these claims Brownell certainly has his work cut out for him. Over the 160 years since its dissolution, the Ruskin marriage has become lodged in popular imagination as a real-life version of Middlemarch's misalliance between Casaubon and Dorothea. It's never spelled out that Casaubon fails to consummate his marriage – you have to rake through Eliot's layered prose to find the clues – whereas in Ruskin's case the evidence was cut and dried. Given that a medical examination had confirmed that Effie was indeed still a virgin after six years of marriage, Ruskin made no attempt to contest the charge. This, though, suggests Brownell, was all part of his cunning plan. The celebrated author of Modern Painters was prepared to let the world think he was impotent if it meant that he could get rid of the woman who had ruined his life.

Still the question remains: why on earth had Ruskin not embarked on joyous honeymoon sex with Effie before sourness set in? In a statement that was meant to stay private but inevitably spread, Ruskin claimed that on the wedding night he had discovered that his bride's "person" was "not formed to excite passion". On the contrary, "there were certain circumstances in her person which completely checked it".

Exactly what Ruskin meant by suggesting that Effie's body disgusted him has been the subject of wild speculation down the decades. In the swinging 1960s Mary Lutyens famously suggested that Ruskin, a virgin who had grown up looking at classical statues, was horrified to discover that Effie had pubic hair. But when it emerged that Ruskin had caught sight of dirty postcards during his time at Oxford, Lutyens was obliged to revise this wild biographical punt. Another author, still reluctant to give up the idea of Ruskin as a hopeless square, more at home with flying buttresses than warm flesh, floated the idea that Effie's menstrual blood had thrown the 29-year-old bridegroom off his bedroom stride. When that theory too looked set to buckle, the next best hypothesis was simply that the bride must have smelled, as most of us would if obliged to endure our wedding day lagged up like an old boiler without the aid of anti-perspirant.

Despite a clear case of "not proven", the effect of Lutyens's intervention was to turn Ruskin into a pantomime villain of Victorian domestic life: misogynistic, cruel, bordering on the sexually insane. Brownell's job, as he sees it, is to restore Ruskin to a more favourable perch in the popular historical narrative. Quoting from Gray family letters, Brownell revives the theory, current at the time but since allowed to lapse, that Effie had married Ruskin only in order to save her father's finances. Robert Gray was an unusually careless Scottish lawyer who had lost a bundle on the railways and was desperate to gamble his remaining asset – his pretty eldest daughter – in a bid to get a lien on the Ruskin family's deep pockets.

For Brownell, then, Ruskin's decision not to sleep with Effie becomes the reasonable response of a man who is bitterly hurt to discover that he has been married for his money. It was his way of buying time. To add to his trauma, Brownell suggests, Ruskin quickly realised that Effie had no intention of pretending that this was anything other than a marriage of convenience. While he, Casaubon-like, had assumed the merry teenager would be happy to spend her days trailing dustily after him as he surveyed the cathedrals of northern France, Effie was soon revealing herself to be not so much a Dorothea as a Rosamund. Dressed to the nines, she threw herself into Venetian expatriate life during the couple's stay in 1849 and again 1852. Wherever she went she created a stir among the handsome Austrian officers who were to be found lounging on the corner of every palazzo. There was intrigue, bad feeling, missing jewels and even a duel.

From this point, Brownell argues, Ruskin did everything he could to bring about the end of the marriage, most obviously and oddly by encouraging Effie to spend time alone with other men. By pushing her into the arms of potential lovers he hoped to panic the Grays into thinking that he might have grounds for divorce. If his plan succeeded, Effie's parents would be stampeded into seeking an annulment on the grounds of non-consummation, an altogether less bruising process for all concerned. The climax came in the summer of 1853 when the young painter John Everett Millais was famously invited to travel with the Ruskins to Scotland and found himself sharing a cottage with Effie while Ruskin took himself off to the local hotel to write up what he chillingly termed his "evidential diary". The inevitable happened, and the housemates fell chastely in love, a holiday romance that would form the basis for Effie's long and happy second marriage.

Whether turning Ruskin into the injured party of this hoary old drama really does restore his potency is a moot point. Certainly the reluctant bridegroom who emerges from Marriage of Inconvenience is no longer an unworldly and neutered intellectual but a righteously angry man determined to rid himself of an artful minx. The problem, really, is that Brownell is not content simply to lay out his thesis and let us make up our own minds. Instead he feels obliged to snipe at Effie in much the same way that people sniggered at Ruskin throughout the rest of his long life. He takes every chance to remind us that Effie was a late riser (Ruskin got up at a wholesome 6.30) and can't help mentioning that she was too "restless" to sit still for long enough to have her photograph taken. When she engages an Italian tutor in Venice, it turns out to be simply in order "to facilitate her shopping". As Effie twinkles her way around the ballroom filling up her dance card, Brownell peers at her disapprovingly from the side-lines, purse-lipped at the way that young Mrs Ruskin is setting her cap at "yet another man".

What really went on in the Ruskin-Gray marriage is, despite what biographers like to claim, unrecoverable now. But rather than considering why this might be, Brownell simply wraps another thick textual blanket around the mystery, muffling it still further. You long for Janet Malcolm to come along and repeat her brilliant trick of 20 years ago when she trained her sights on the unhappy marriage between Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. In the absence of anyone prepared to do this kind of spoilsporting on the Ruskin-Gray marriage, its pop-cultural credentials shine as bright as ever. If proof were needed, consider this. In 2011 a new film called Effie Gray, written by Emma Thompson, finished shooting. Since then it has been languishing in the limbo of the courts, amid claims and counterclaims about who has the right to say what really happened in the Ruskins' bedroom all those years ago: it is finally due for release in May.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion