Masters: John Ruskin and His Influence on American Art

During the second half of the 19th century a single writer held enormous sway over the hearts and minds of American artists, critics, and their public.

During the second half of the 19th century a single writer held enormous sway over the hearts and minds of American artists, critics, and their public.

by John A. Parks

By the middle of the 19th century, as the United States emerged from an agrarian economy to become a mighty industrial power, it began to foster a climate in which the arts could at last be pursued seriously. Along with this development arose inevitable questions for critics, artists, and art collectors: How was the art of the new nation to be judged? Was it to be set against the same standards as European art, or was it to be rated as a peculiarly American affair? Added to this, the rise of Romanticism in Europe fostered the creation of art in which the imagination and personality of the artist held sway over nature and God, a notion that did not sit well with the Protestant community in the United States. The intellectual status quo had already been challenged in the first decades of the 19th century by the Transcendentalists, headed by Ralph Waldo Emerson, who maintained that God was imminent in nature, that His presence could be intuited by any individual, and that no organized religion was required.

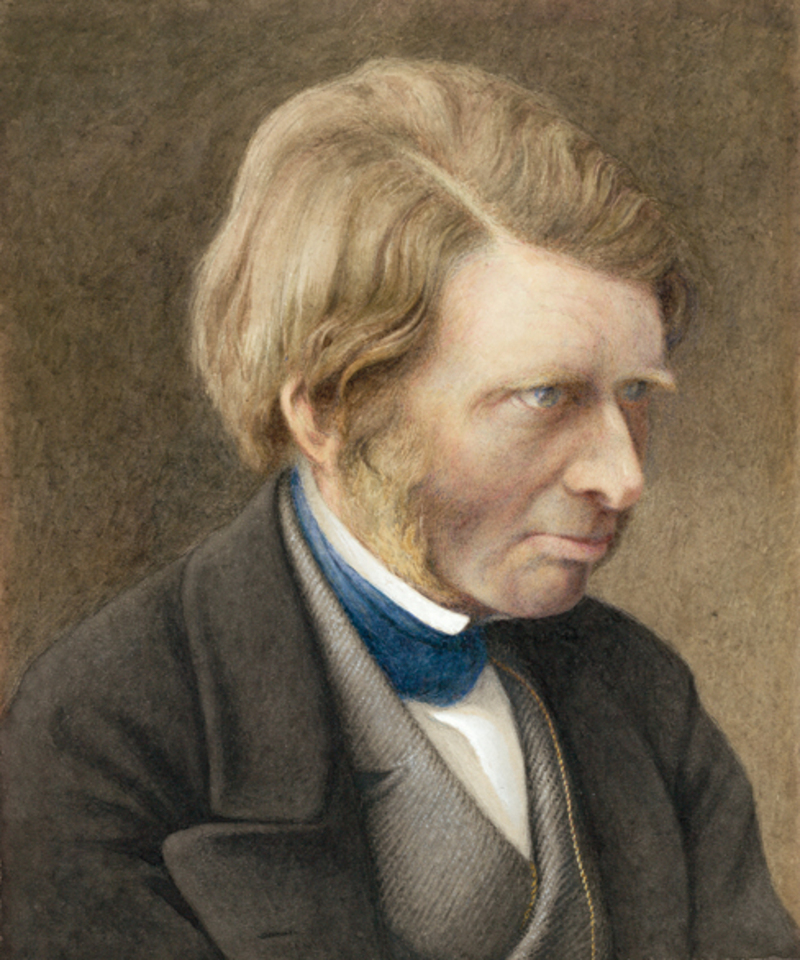

The answer to these and many other pressing and alarming questions of the day were answered, at least to the satisfaction of a very large number of artists and critics, by the writings of one Englishman, John Ruskin. From the publication of the first American volume of his Modern Painters, in New York in 1847 all the way to the writer’s death in 1900, Ruskin’s ideas on art, architecture, sculpture, and eventually social and political issues exerted an enormous influence over American intellectual and artistic life. This spring an exhibition at the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, “The Last Ruskinians: Charles Eliot Norton, Charles Herbert Moore, and Their Circle” demonstrates the direct influence of Ruskin on a group of American watercolorists associated with the short-lived American Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Fascinating as this is, it is even more interesting to consider the wider influence that Ruskin exerted on the development of American art.

Ruskin’s Background and Upbringing

John Ruskin was born in London in 1819, the son of a successful sherry importer and the daughter of an innkeeper. Great things were expected of the child right from the start, and his parents set their sights on a career as a poet or a preacher. Educated at home, and immersed from the beginning in great literature and lengthy Sunday-morning sermons, Ruskin displayed a precocious literary ability from an early age. The week’s studies were capped on Sunday afternoons by the study of yet more sermons, and the boy soon took to writing his own and declaiming them with great verve for the benefit of his family. When he eventually went up to Oxford as a student his mother came along too, taking rooms in the High Street so that she could better keep an eye on the young him.

The young man did not disappoint. He won the prestigious Newdigate Prize for literary achievement and seemed positioned to fulfill his parents’ dreams. But against all this study and endeavor there had entered into Ruskin’s life another, and perhaps more powerful, experience. Each summer, during his upbringing, the family would leave their pleasant and secluded home in Herne Hill in South London, and travel northward by coach to the Lake District. For young Ruskin, exhausted from his literary studies, this transition was utterly magical. The release from sermons, tracts, and texts was accompanied by the sight of mountains, lakes, and vast panoramas. It is hardly surprising that he invariably found himself in a state of quiet, transcendent bliss at these moments.

|

| Fragment of the Alps by John Ruskin, ca. 1854–1856, watercolor and gouache over graphite on cream wove paper, 13 x 19½. Gift of Samuel Sachs. |

Later, as a teenager, he was taken to the Alps, and there these feelings of glorious release and reverence were magnified enormously by the colossal scale of the landscape. Already an accomplished writer, Ruskin wrote copiously and brilliantly of the feelings inspired by his exposure to these natural wonders. “The whole valley was full of absolutely impenetrable wreathed cloud, nearly all pure white, only the palest grey rounding the changeful domes of it; and beyond these domes of heavenly marble, the great Alps stood up against the blue … not wholly clear, but clasped by, and intertwined with, translucent folds of mist, traceable, but no more traceable, than the thinnest veil drawn over St. Catherine’s or the Virgin’s hair by Lippi or Luini.” Ruskin was not, of course, the first person to experience intense feelings in front of nature; indeed, this source of inspiration was very much in the air at the time. The English poet William Wordsworth was making an enormous mark on the civilized world with poems that seemed to suggest that God could be apprehended through a heightened awareness of nature. In his poem Tintern Abbey, he speaks about seeing in a natural setting “a motion and a spirit that impels / All thinking things … / And rolls through all things." This idea of divine presence made apparent in nature certainly had its effect on Emerson and his followers in the United States by the middle of the 1830s. When Ruskin’s work arrived there in 1847 the ground was already well prepared.

Ruskin’s Interest in Art and Architecture

Ruskin’s early command of language and his intense sensitivity to nature were joined by an interest in art and architecture. He regularly visited exhibitions of the Old Water-Colour Society with his father and received drawing and watercolor lessons himself, displaying considerable talent for close observation and concentration. And it was thus, at the age of 13, that when he came upon a work by J.M.W. Turner reproduced as a frontispiece for a book, he felt strangely moved by its airy atmospheric space. The attachment that the young man formed to Turner’s vision was to prove fateful for the art world on both sides of the Atlantic. When Ruskin was 17 he saw three of Turner’s paintings at the Royal Academy, in London, and became utterly convinced that he was looking at true greatness. In these paintings he found his own feelings played back to him, a kindred spirit speaking his thoughts about the power and wonder of nature in a completely different language. Turner, wrote Ruskin in his diary, was “beyond all doubt the greatest of the age; greatest in every faculty of the imagination, in every branch of scenic knowledge, at once the painter and poet of the day.”

|

| Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy by Henry Roderick Newman, 1884, watercolor over graphite on off-white wove paper, 25½ x 31. |

Although these days the world is generally in happy agreement with Ruskin’s assessment of Turner’s painterly powers, the issue was in some doubt during the artist’s lifetime. Turner had begun his career as a dazzling marine and landscape painter, capable of an intense and convincing realism. By the middle of his career, however, he had moved on from the conventions of 18th-century painting, with its admiration of classical models, and had begun to produce work in which the very forces of nature seemed freed from the objects of this world. The artist painted scenes in which winds, fogs, and mists were conjured from dabs of color and gestures of paint with little regard for the careful building and description of form prized by earlier generations. He was accused in the press of putting his imagination ahead of his observation of nature. He was failing, claimed the critic of Blackwood’s Magazine in 1836, to be true to nature. A public controversy ensued.

It is difficult for us today to imagine a world in which there is an aesthetic orthodoxy to which more or less everybody subscribes. We think nothing of going to the museum and strolling through rooms in which we might enjoy a Jackson Pollock splash painting, a Richard Estes Super Realistic painting, a painterly rendition by Wayne Thiebaud and some vast, cataclysmic wonder by Anselm Kiefer before heading off to an overpriced restaurant to chat about it all. Not so in the 19th century, when society was extremely careful about what could and couldn’t be considered worthwhile art.

The groundwork for appropriate criticism and appreciation of painting had been laid out for the British public the century before by Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first president of the Royal Academy, in a famous series of discourses. In his discussion of landscape painting, Reynolds had advanced a theory of the proper relationship of art to nature along the following lines: The work of the artist, he held, was to become so familiar with nature, through drawing and painting, that he would be able to intuit what parts of it most perfectly expressed the presence of the divine and the beautiful. He would then exercise his powers of invention in reconstituting these elements to present a version of “general nature,” which would display the essential beauty of the world. Moreover, since this task was liable to be extremely difficult and time-consuming, the artist might do well to follow carefully the work that had come before him, and in particular to follow the model of painters such as Claude Lorraine and Nicholas Poussin, who had already trodden this path and produced works of sublime beauty. The critic’s task in such cases could almost be reduced to the work of perceiving how close or how far the artwork resembled the vision of Claude or Poussin. This theory was obviously only workable if artists toed the line and worked at producing variants of classical models. But then along came Turner with an approach that looked nothing whatsoever like these venerable artists at all. The critics accused him of deserting the accepted path and making paintings that exalted the imagination and personality of the artist rather than the beauty and truth of nature. Their condemnation incensed young John Ruskin. His own experience of nature told him that Turner’s vision was fundamentally and powerfully true. He felt it in his bones, and he was equipped to make his feelings felt by the world. Inspired, he sat down to write an impassioned defense of Turner, a task that would give rise to the first of three enormous volumes titled Modern Painters.

|

| Peacock Feather by Charles Herbert Moore, ca. 1879–1882, watercolor and gouache on off-white wove paper, 12 x 9¾. Gift of Dr. Denman W. Ross. |

The Influence of Modern Painters

Modern Painters, the first volume of which was published in London in 1843, set out to show that the modern masters, and in particular Turner, were superior to the Old Masters. This was no small task, and Ruskin brought to bear on it all his considerable knowledge of aesthetics and art. He put forward a copious analysis of the qualities by which paintings might be judged, and he set out to prove in case after case that Turner’s observation of objects in the world was actually more truthful and more accurate than those of the supposed masters. Although much of the argument, drawn out over hundreds of pages of grandiloquent English, is somewhat daunting for the contemporary reader, a number of principles quickly impress themselves. Like Reynolds, Ruskin felt that beauty emanated from the understanding of the work of God in nature. But Ruskin believed that any particular of nature could be felt as the product of the divine. The task of the artist’s imagination was in seeing and eliciting this. “It is only by the habit of representing faithfully all things, that we can truly learn what is beautiful, and what is not,” he wrote in Modern Painters. The artist, by a close and careful observation of nature in any of its manifestations, might arrive at a vision that displays the truth and beauty of God and His works. In Ruskin’s scheme, therefore, there is no longer any need to base the artist’s vision on that of previous painters such as Claude or Poussin. This idea may not strike the modern reader as revolutionary, but at the time it was genuinely freeing. Artists were essentially invited to go off and explore the world safe in the knowledge that through insight into whatever they discovered, they were doing the right and moral thing. In Ruskin’s world then, the aesthetic truth was also a moral truth.

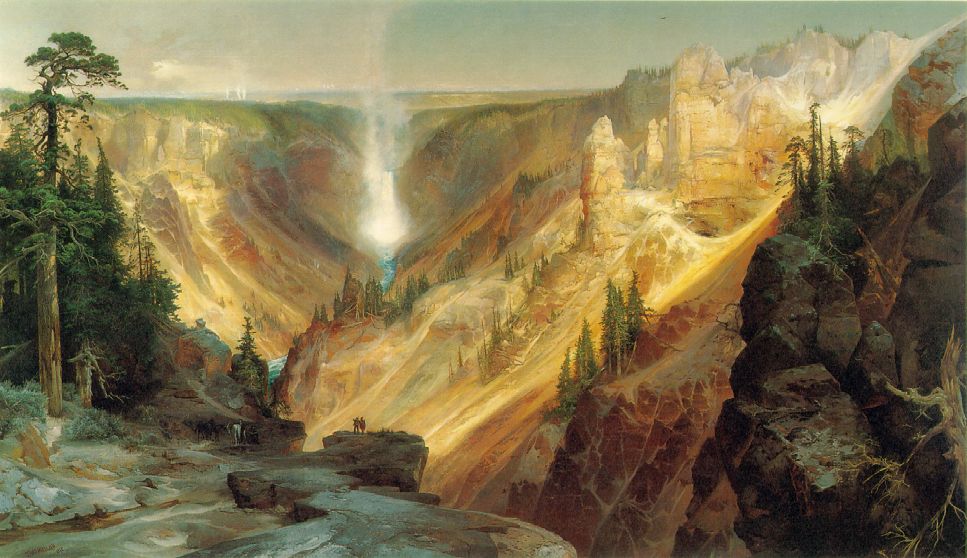

Returning to the somewhat distant and provincial world of the United States in 1847, it is easy to see why such an idea would gain popularity, especially since it was couched in a fervent language and rhetorical style that the readership intuitively recognized as coming from the world of Protestant sermonizing. Ruskin was essentially saying that nature was the ultimate arbiter: follow nature and you find God and beauty. “No great school ever yet existed which had not for its primal aim the representation of some natural fact as truly as possible,” he wrote. And of course the one thing that America had in great abundance was natural facts—millions of square miles of virgin forest and mountain all waiting to be painted. Art could now become both an aesthetic and a religious quest freed from the dominance of centuries of European painting. This was the magic brew that Ruskin had concocted and that American artists found utterly intoxicating.

|

| Bird’s Nest by William Henry Hunt, ca. 1855–1860, watercolor with white gouache on white board, 6½ x 10. |

Ruskin’s Modern Painters was received with enthusiasm in the American art community, and in early 1855 a magazine titled The Crayon appeared that was devoted to the English critic’s ideas and writings. The main force behind the magazine was William J. Stillman, a young painter who had first come across a copy of Modern Painters in Frederic Edwin Church’s studio in 1848. Stillman went to England and met Ruskin in 1850 and was as much impressed by the critic’s strong Calvinism as by his views on art. Once The Crayon got going, it was widely read by both artists and intellectuals, and the magazine published writings by Asher B. Durand as well as many of the leading critics and artists of the day. John Durand, the son of the artist and a financial backer of The Crayon, remarked that Ruskin “had developed more interest in art in the United States than all other agencies put together.” It was through this magazine that Ruskin’s broader message of truth to nature in all its aspects influenced the great American painters of the 19th century, including Durand, Church, John Kensett, and Albert Bierstadt. "Every herb and flower of the field has its specific distinction, and perfect beauty … its peculiar habitation, expression and function," wrote Ruskin in the introduction to the third volume of Modern Painters. "The highest art is that which seizes this specific character, which assigns to it its proper position in the landscape. … Every class of rock, every kind of earth, every form of cloud, must be studied with equal industry, and rendered with equal precision.” The deep belief that many American painters still have in the power of close and faithful observation of the natural world owes a debt to the sense of moral worth that Ruskin’s writings gave to this approach.

Ruskin’s Influence on the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Although Ruskin’s inspiration for wading into the world of art criticism came through the paintings of Turner, his own influence quickly fostered a following from a group of artists with very different aims. Ruskin was approached in 1851 by William Holman Hunt, who had found Ruskin’s call to examine the particulars of nature to be inspiring. Around Hunt had formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of painters including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais. They were interested in returning to the condition of art prior to the era of Raphael, a time when they imagined that artists addressed nature directly before the grand classical manner had emerged. Ruskin wrote in support of these artists, although his own interests were considerably broader than those of the group. In practice, these new painters pursued a meticulous approach to representation in which the particular details of the world threaten to overwhelm matters of composition and form. They are paintings in which every blade of grass and every hair of the head of all the characters are rendered with equal attention.

|

| John Ruskin (1819–1900) by Charles Herbert Moore, ca. 1876–1877, watercolor and white gouache over graphite on off-white wove paper, 13¾ x 11. Gift of the Misses Sara, Elizabeth, and Margaret Norton. |

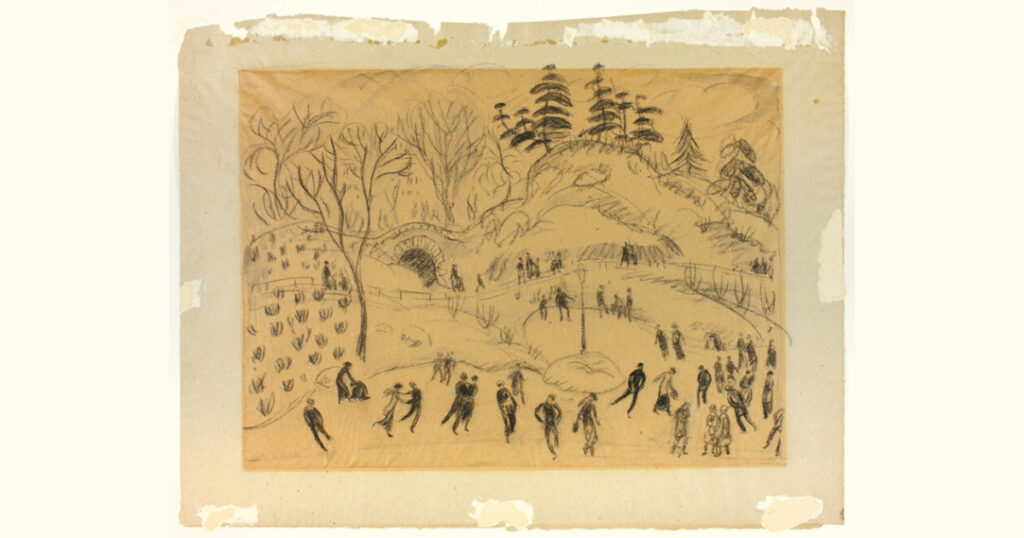

To this enterprise painters such Rossetti and Millais were to add a somewhat sentimental and literary kind of storytelling based on a rather romantic understanding of medieval models. It was this meticulous and painstaking style that was adopted by the American incarnation of the Pre-Raphaelites. This was a group formed in 1863 in the New York studio of the English expatriate artist Thomas Charles Farrer and known as the Association for he Advancement of Truth in Art. The principal members were Farrer, John Henry Hill, John William Hill, Charles Herbert Moore, Henry Roderick Newman, and William Trost Richards. These artists did not follow their English counterparts in terms of elaborate narrative paintings but pursued their careful and highly detailed observations of nature. They also published a periodical, The New Path, in which they presented a lively combination of reviews and essays.

The power of Ruskin over this group was considerable, not merely through his ideas on art but also directly in the form of studio. In 1857 Ruskin published a highly practical guide to painting and drawing titled The Elements of Drawing. Ruskin had been persuaded to take up the teaching of art in the 1850s at the new Working Men’s College, in London, where one of his colleagues was Rossetti himself. The principles Ruskin espoused in his book were delicacy, close observation of the details of nature, and a watercolor technique in which broken areas of brilliant local color were built to obtain a rich and dazzling surface using a hatching technique. The book is also filled with many highly practical and thoughtful exercises, tips, and approaches to making art. Although directed at amateurs the book was widely read by professional artists on both sides of the Atlantic. No less a figure than Winslow Homer learned his watercolor technique by reading The Elements of Drawing, and so pervasive was its influence on color that Claude Monet himself was quoted by a British journalist in 1900 as saying that “Ninety percent of the theory of Impressionist painting is in … Ruskin’s Elements of Drawing."

The Last Ruskinians

Certainly watercolor, with its immediacy and portability, was an ideal medium for American artists intent on going out into nature, and Ruskin’s instructional book arrived at a timely moment. Thousands of pirated copies were printed and sold in America, and the book remains in print to this day. Paintings executed with the delicate hatching and brilliant broken color suggested by Ruskin form the focus of the current exhibition at the Fogg Art Museum. Here we see the English artist William Henry Hunt spending weeks painting every twig and feather in a bird’s nest. Charles Herbert Moore must have spent a similar amount of time rendering a peacock’s feather in exquisite and somewhat painful detail. We can see too that Ruskin himself, when he took up the brush to paint Fragment of the Alps, was inclined to a similar approach, rendering a large rock through a laborious catalogue of its surface detail rather than summoning up its gross girth and weight as a more classically trained artist might have done. The effect of this piece, for all its intensity of observation and industry, is somewhat lightweight and fragmentary. In fact, Ruskin would often leave works unfinished, stranding areas of intensely observed detail in the middle of blank canvases before giving them away to friends. Other followers in this exhibition include Henry Roderick Newman, who took the Ruskinian approach to Florence, producing in Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy a record of every brick and stone of the ancient scene in front of him. The artist used gouache body color over the watercolor to increase the density of the rendering and control the lights, a technique advocated by Ruskin in The Elements of Drawing

Although the fine quality of the paintings in the exhibition is evident, they also display the weaknesses of this heavily detailed approach. There is a general lack of invention in terms of composition and little understanding of how the color and tone throughout an entire picture can be balanced and orchestrated. To be fair to Ruskin, he always said that this process of looking very carefully at the world was only a prelude to a more mature stage of artistic development like that exhibited in Turner’s later work, where the invention and imagination of the artist would take a larger role. In fact, in his later writing he developed a strong sense of the limits of slavish devotion to facts. “Always look for invention first,” he wrote in his volume on architecture, The Stones of Venice, “and after that, for such execution as will help the invention, and as the inventor is capable of without painful effort, and no more. Above all, demand no refinement of execution where there is no thought, for that is slaves’ work, unredeemed. Rather choose rough work than smooth work, so only that the practical purpose be answered, and never imagine there is reason to be proud of anything that may be accomplished by patience and sandpaper.”

Ruskin’s Legacy

Posterity has been somewhat unkind to Ruskin. This is due, in part, to the unfashionable quality of his prose, so revered in his own time with its grand cascading sentences and its vast grasp of vocabulary. To the modern ear it seems outmoded, long-winded, and suspiciously overstyled. And then Ruskin is also the victim of the somewhat grotesque prurience of his biographers. Ruskin’s first marriage to Effie Gray in 1848 was never consummated due to some kind of physical aversion on Ruskin’s part, the exact nature of which was never revealed. The marriage was eventually annulled, causing a considerable scandal, and the young woman went on to marry Ruskin’s protégé John Everett Millais, with whom she had many children. Ruskin himself confined his future romantic attentions to very young women but was refused by the girl he most admired, Rose la Touche, to whom he proposed when she was just 17. Rose died several years later, and Ruskin quite literally lost his mind. He got it back after a number of months but he was never the same.

In 1877 Ruskin became embroiled in yet another controversy when he harshly criticized a painting by James Whistler on exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery, in London. "I have seen and heard much of Cockney impudence before now," Ruskin famously wrote, "but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public's face." Whistler was American, of course, not a Cockney; the appellation was simply meant to insult the painter by consigning him to a lower class. The leading light of the aesthetic movement had probably annoyed Ruskin by championing the art of Turner, Ruskin’s first love. Whistler, a man with an enormous ego, decided to sue Ruskin for libel, and a curious court case ensued in which the merits and values of various kinds of art and art-making were debated in court. Whistler won the case but was awarded only a copper coin in damages. The costs of the case bankrupted him. Ruskin was able to pay his own costs through a subscription raised by his friends, but the courtroom loss was a blow to his precarious mental state. In 1869, Ruskin was elected the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford and gave many well-received lectures. Reinstated after a break in 1883 he alarmed his audiences by extolling the virtues of the minor illustrator Kate Greenaway, whose sentimental line drawings of smiling little girls now looked better to him than all the great masters of European art. He even wrote to her suggesting that she do more drawings of naked children. Meanwhile his writings were inclined to make less and less sense, combining moments of great brilliance with complete non sequiturs and sometimes delving into imagery and ideas bordering on madness. It was a sad unraveling of a great mind. Ruskin spent his last years living in seclusion in a large dilapidated house on the shores of Coniston Water in his beloved Lake District. The walls were hung with Turners, but the house was uncomfortable and poorly decorated. Ruskin wrote on in between increasingly frequent bouts of madness until he died in 1900.

Ruskin’s legacy lives on in the still lively interest in realism in American painting. He would have been delighted, no doubt, in the current vogue for plein air painting and its pleasure in the direct experience of the wonders and wealth of nature. On the other hand he might have been saddened by the rank commercialism and lack of lofty ideals in the contemporary world of art. “All great art is the work of the whole living creature, body and soul, and chiefly of the soul,” he wrote in The Stones of Venice. “But it is not only the work of the whole creature, it likewise addresses the whole creature. That in which the perfect being speaks must also have the perfect being to listen. I am not to spend my utmost spirit, and give all my strength and life to my work, while you, spectator or hearer, will give me only the attention of half your soul. You must be all mine, as I am all yours; it is the only condition on which we can meet each other.”

They don’t make critics like that anymore.

John A. Parks is an artist who is represented by Allan Stone Gallery, in New York City. He is also a teacher at the School of Visual Arts, in New York City, and is a frequent contributor to American Artist, Drawing, Watercolor, and Workshop magazines.

Have a technical question?

Contact UsJoin the Conversation!