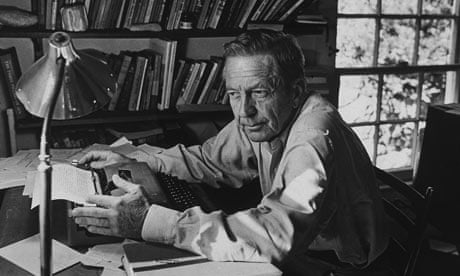

On a damp and unseasonably cold summer morning, Susan Cheever and I leave her apartment in New York and drive to Ossining, in Westchester County. We are going to visit the stone-ended Dutch Colonial she lived in as a teenager, a house her 90-year-old mother, Mary, still miraculously inhabits. Susan, who is 65, begins our journey with the slightly ragged air of one who has packed for a long trip a little too fast; her ultimate destination is Bennington College, Vermont, where she teaches non-fiction writing. But this doesn't last long. Barely have we left the city than I notice that her face is suffused with a warm, proprietorial glow. Rather to my amazement, she is enjoying our talk, which is all about her father, John Cheever, the great American writer. I had expected it to be painful. "Oh, yes," she says, when I mention this. "I'm sort of enchanted by my family. I have this weird family worship." She peers determinedly through the misted windscreen. "Wait till you see the house! This beautiful building that is now the ugliest place on earth. It's like the House of Usher."

Of course, she is more than prepared for my questions. How could she not be? John Cheever died in 1982, at the height of his fame as the bestselling, Pulitzer prize-winning author of five novels and some of the most brilliant short stories ever published. But in the years after his death a stream of revelations about his life poured into the public domain, muddying the blue-bright waters of his legacy with distressing efficiency. His life has been nothing if not picked over. Susan came first, with her memoir, Home Before Dark (1984), written to disable the bomb of an unauthorised biography. The book confessed the extent of her father's alcoholism, and gently noted his bisexuality; in the last years of his life, she wrote, he had found love, of a kind, with a young man she called Rip.

Next came a volume of Cheever's letters, edited by Susan's brother, Benjamin, who wrote in his introduction of how difficult it had been to discover the extent of his father's homosexuality, and then coolly thanked the composer Ned Rorem for revealing that "for my father, orgasm was always accompanied by a vision of sunshine, or flowers". Finally, in 1990, Cheever's journals, which run to some 4 million words, were auctioned by the family, and extracts published in the New Yorker, and in a single volume.

The journals contain some of the best sentences Cheever ever wrote, but, my God, they are horrifying. The pain, the loneliness, the secrecy, the shame: Cheever, an imposter in his own life, turned self-loathing into an art form. His image as the poet of suburbia – the Ovid of Ossining, Time magazine called him – was thus dealt a possibly mortal blow, the moments of darkness in his stories now taking on new menace; the moments of grace, a sudden emptiness. Was ever a man's outward appearance so at odds with his inward condition? His friend John Updike thought not, and shook his head sadly at this psychic chasm, hoping against hope that Cheever's fiction, with its startling glimmers of optimism, its sense always of moving towards the light, would somehow prevail.

Now, nearly two decades on, there is Cheever: A Life by Blake Bailey, previously the biographer of another suburban drunk, Richard Yates (a coincidence: before their move to Ossining, the Cheevers rented a house in which Yates had also once lived). Bailey's book is almost 700 pages long, and so tirelessly detailed, even Cheever's children have found surprises within its tidy bulk. "When I first got the manuscript, I did so electronically," says Susan. "I'm ashamed to say that I used the 'find Susan' method of reading it, first off. That took about an hour. OK, I thought: there's nothing too awful about me. Then I read it from the beginning. It sounds narcissistic to say so but I found it fascinating. My memory only kicked in when he came home from the war. So his childhood: that was new. And then, I didn't know how much gay activity there'd been…"

Susan loves the book; she thinks Bailey's version of her father is truthful and unflinching, and that it captures him in some essential way. But she wonders about its diminuendo ending: the chapters which cover the last seven years of his life when, against all the odds, he dried out. "For me, the end of his life is triumphant. He stops drinking. He writes what I think is his best book [Falconer, a novel about a drug addict, serving time for the murder of his brother, who has an affair with another prisoner ]. He became the man he meant to be."

It's certainly true that Bailey, though both a devoted admirer of Cheever's writing and a compassionate biographer, does not present the end as jubilant; his late Cheever is, in some ways, as imprisoned as his early Cheever. But there is one obvious reason for this. "Rip', Cheever's last lover, whose real name is Max Zimmer, co-operated with Bailey on the book, and described to him his relationship with the older writer in painful detail, presenting himself as a poor and desperate young man with no other place to go but his patron's bed (Max, who comes from a Mormon background and is now married with children, had been a student of Cheever's, and longed to be published).

The sex, he tells Bailey, disgusted him. But, he implies, he was subtly coerced into it. What's more, Cheever continued to be conflicted and clandestine about the relationship, treating Max like little more than a servant in company.

Susan, though, doesn't buy this. She believes that her father wanted to live with Max openly; that they had even discussed this. "Without alcohol, he became himself," she says. "Had he lived longer, he would have come out. That's what was happening, and that would have been such a happy thing. He simply hadn't seen his way to how that could happen without causing everybody pain."

Is she upset about Max's story? "Oh, I'm sad about it. Max was like a brother. He was very sweet and kind after my father died. He said to Blake that he was glad we made room for him in the pew [at Cheever's funeral]. But he was a pall bearer! Come on! I know what happened back there."

It was Benjamin Cheever who suggested to Bailey that he might write, unauthorised but wholly unimpeded, a new biography of his father; Ben's wife, Janet Maslin, a critic at the New York Times, had admired his Yates biography. Susan was less keen – until she had dinner with Bailey, at which point it occurred to her how much fun it would be for her elderly mother to have "an attractive and intelligent man dancing attendance on her". Bailey visited Mary Cheever at the house in Ossining often, and his book duly contains an indelible portrait of one of the most complex, and, at times, cruel, marriages it is possible to imagine. "It was quite a European marriage," says Susan, passing me her bag so I can search it for toll money. "They were people who felt their feelings weren't necessarily a reason to shatter a family. They certainly hurt each other plenty but they didn't necessarily see that as a reason for divorce."

Didn't she wish, sometimes, that they would just separate? As well as novels and two memoirs about her parents, Susan, who has been married three times, has written books about both her own alcoholism (she hasn't had a drink for two decades) and her propensity for sexual obsession. It's hard, from the outside, not to wonder if all the misery hadn't in some way been handed down.

"I don't know whether, in the end, we would all have been happier if he'd left her, or she'd left him. When Blake's book came out [in the US], I was worried people would call me, and say: 'Oh, I'm so sorry [about your childhood].' But if I'm at peace with it, they should be. There was something going on in our family that was not visible from the outside. It's not that we are so successful or fabulous but all three of us [she and Benjamin, also a writer, have a younger brother, Federico, known as Fred, a law professor] have really done pretty well. I've given a lot of thought as to what it might have been that was going on. Because we're not the walking wounded. First of all, my father was incredibly funny. Sometimes it was really mean; you were laughing and crying at the same time. He was completely unscrupulous about what he would do to make you laugh. But we were all laughing, and there is something about laughing that is profoundly healing. My other theory is that there is something profoundly healing about reading, and we were reading all the time. Whatever it was, I'm grateful for it. I just thought my parents were so interesting. I still do. My mother… well, you're about to meet her. I never know what she's going to say next, even after all these years."

John Cheever was born in 1912 in Quincy, Massachusetts, and right from childhood had delusions of grandeur; when his shoe salesman father fell on hard times and began drinking, and his mother, to keep the family from the streets, opened a gift shop – all doilies, china kittens and Toby jugs – he regarded her venture with lavish shame. Hadn't his father always told him to remember he was "a Cheev- "? Apparently his parents' plight had almost nothing to do with circumstance – the New England shoe and textile industries were in long decline – and everything to do with what he feared was their unique strangeness and vulgarity. Later, when Mary, his well-bred wife, teased him about the family "gift shoppe", the memories this stirred caused "an actual sensation of discomfort in [his] scrotum".

Only his older brother, Frederick, seems to have been a source of comfort: the most "significant relationship in his life", he once told a psychiatrist. Bailey, based on his reading of Cheever's journals and an interview with a confidant, goes so far as to suggest that the relationship may have been incestuous.

But whatever the nature of their bond, it was Frederick who at first helped his brother financially when he moved to New York in the hope of becoming a writer, an ambition it did not take him long to fulfil. In his early 20s he began selling stories to the New Yorker, the magazine that would publish his work for the next four decades. Even so, he remained desperately poor, living in a succession of one-room garrets, surviving on stale bread, raisins and a daily bottle of milk.

Even after he married Mary Winternitz, whose father was a famous surgeon, and whose family spent their summers on their 50-acre New Hampshire estate, Treetops, with its swimming pool and tennis court, his financial struggles continued, and Cheever worried he would not be able to keep Mary in the style to which she was accustomed: a style he longed to claim for his own, even as, in his journals, he professed to despise it.

Slowly things improved. After Mary and John started a family they decided to move to the suburbs, first to a rented house in Scarborough and then, finally, to the house in Ossining (incidentally, as Benjamin Cheever will later tell me, Don Draper in the TV series Mad Men, another man who feels like an imposter in his own life, lives in Ossining; this cannot be a coincidence). Cheever adored his new home, and liked to boast of its age (he claimed it had been built in the 18th century; in fact it dates from 1928). He also loved Westchester County. It wasn't only that here he could pose in a Fair Isle sweater, a labrador at his feet, and engage in manly pursuits such as skating, chopping wood and scything (Cheever was inordinately proud of his scything). The wooded valleys seemed to speak to something in his soul. "We have a nice house with a garden and a place outside for cooking meat, and on summer nights, sitting there with the kids and looking into the front of Christina's dress as she bends over to salt the steaks, or just gazing at the lights in heaven, I am as thrilled as I am thrilled by more hardy and dangerous pursuits, and I guess this is what is meant by the pain and sweetness of life," announces the narrator of the story "The Housebreaker of Shady Hill". For Cheever, there is something luminous – numinous, even – about life in commuterland. Perhaps he thought it could save him.

But it couldn't, of course. By the early 1960s Cheever could justifiably call himself a success. He had a beautiful and able wife (Mary was a teacher and poet), and three children. He had the home of his dreams. After struggling for some years to write a novel, he had finally published one – The Wapshot Chronicle – and it had received good reviews, and sold well. Time magazine had made him its cover star. However, behind the scenes, all was not well. Cheever was often drunk before lunch. As a result, he was mostly impotent, at least so far as Mary was concerned. His wife had withdrawn from him (who could have blamed her?), and Cheever would devote pages of his diaries to railing at her for her coldness.

Sometimes, she would give him the silent treatment. On other occasions they would fight, nastily. Cheever would remind her of the insanity in her family. "What about the times you couldn't get it up?" she would reply. And beneath it all there was his escalating terror of his own sexual desires. Cheever had already enjoyed sexual encounters with at least three men by this point, among them the photographer Walker Evans, but out in the suburbs his shame about such things grew into an abiding fear. In his journals, this manifests itself in the form of homophobia. Cheever would often describe his distaste for gay men, whom he regarded as effeminate, even obscene. As for the idea of waking up with a man! "It is one thing to tear off a merry piece behind the barn with the goatherd but one wouldn't, once your lump is blown, want to take it any further." After a night spent with the writer Calvin Kentfield, he was so filled with self-loathing he temporarily developed agoraphobia.

On and on this misery goes. There is a moment, reading Bailey's book, when you think: I'm going to be spending another 400 pages in this man's company. Can I bear it? Cheever eventually grew so lonely that on the train into New York he would ask complete strangers: "Wouldn't you rather talk than read?" By the late 1960s his drinking was out of control. In his journal he would describe his battles to leave off the gin even until 10 o'clock in the morning; a few "scoops" would be taken in the pantry as soon as the rest of the family had left the house.

In 1975, Cheever was exiled temporarily to Boston to teach at the University. One day John Updike arrived at his door to take him to the Symphony Hall. Disconcertingly, Cheever emerged naked to greet him. Cheever would sit with bums on benches, sharing their fortified wine. When a policeman threatened to arrest him, the writer flashed him a haughty look, and drawled: "My name is John Cheever." He began seeing male prostitutes. Even the rare moments of light were somehow blighted by Cheever's peculiarly toxic form of self-hatred. At the Iowa Writers' Workshop, Cheever met the gay novelist Allan Gurganus. Cheever doted on Gurganus, and yet still he was moved to write of him: "The more he flirts, the more he seems like a woman."

Finally, though, the miracle. In 1975 Cheever returned to Ossining and, on 9 April, Mary drove him to the Smithers Alcoholism Treatment and Training Centre in New York (he tried to jump out of the car on the way, but still: a part of him obviously knew what he had to do). Throughout his treatment, Cheever, an AA sceptic, was by turns ironic and faux humble; a "classic denier", according to one of his psychologists. But it worked. He left Smithers on 7 May, and never drank again. He was able to resume writing his novel Falconer, and when it was published in 1977, he was rewarded with a Newsweek cover (strapline: "A Great American Novel: John Cheever's Falconer"). In 1978 the travesty that all but one of his short story collections was out of print was duly put right with the publication of The Stories of John Cheever. It remained on the New York Times bestseller list for six months, and won the Pulitzer, the National Book Critics Circle award and the American Book award.

And then there was Max Zimmer, whom he met while teaching in Utah. I am at a loss as to what to say about Max; a large part the attraction seems to have been that he had "none of the attributes of a sexual irregular" (in other words, Cheever thought him manly-looking; he was not a hip-waggler). Cheever promised to help Max with his writing, and encouraged him to leave Utah, telling him he would help him get a place at Yaddo, the writer's colony with which Cheever had strong connections.

So they embarked on a relationship – of sorts: in Bailey's book, Max describes one of their early sexual encounters as "just a gruesome thing to have to do". Cheever never did manage to get one of Max's stories published in the New Yorker, or anywhere else, but when, in the summer of 1981, he was diagnosed with cancer, it was often Max who drove him to the hospital for his radiotherapy sessions. In the months before Cheever died – Max having divorced his wife and with nowhere else to go – the house in Ossining became a strange haven. Mary moved Cheever back into the marital bedroom for the first time in years; and Cheever moved Max into the spare bedroom. Mary cooked; Max chopped wood; and Cheever, when he was physically strong enough, would take Max – or another lover, Tom Smallwood – into the woods for sex. (Through everything, Cheever had the most astonishing libido.) Sex with men now commonplace for him, Cheever looked back on his old sad self with something approaching amusement. "Nothing could be more natural," he wrote of his "exertions". And Mary? He now considered his marriage with a kind of prayerful wonder. "The word 'dear' is what I use: 'How dear you are.' It is the sense of moving the best of oneself toward another person. I think this was done most happily within my marriage, although I do remember being expelled to sofas in the living room... I do recall the feeling of moving, rather like an avalanche, toward Mary." It was a funny kind of peace, but it was peace nevertheless.

Susan is right about the house. From afar, gazed at through the dripping greenery, it looks idyllic. But up close, scenes from rackety old horror films do float through the mind. It seems to be fraying elegantly about its edges, as if it were a set design left behind by some long since abandoned movie production. When we arrive, Mary and Ben, who lives in nearby Pleasantville, are waiting for us; at the sound of the car, they come out on to the house's slate steps to greet us. These two are so alike: dark-skinned, long-faced, small and wiry. Mary, in her wide-legged tweed trousers, looks frail – you feel as if you could crush her in your hand, like a potato crisp – and her voice is infamously girlish, like Bette Davis's in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (Susan says that people used to ring the house, hear Mary, and ask: "Is your mother in?") But do not be deceived. Even as she professes ignorance about all manner of prosaic things, you understand that she is beady and knowing and, above all, rather tough. How could she not be? She is Cheever's widow. I find that I have to remind myself of this – it just seems so incredible – and the thought makes me shiver.

Inside, almost nothing has changed since Cheever died, though there is now a strong smell of cat (Mary has taken in a middle-aged woman, a lodger who has 10 cats; "Well, I didn't know she had 10 cats," she says). Even his books are still about the place. The ceilings are low, and it is gloomy; wallpaper gently peels. But Ben and Susan have a delightful attitude to all this. It seems not to get them down. Behind their mother's back, and sometimes in front of her, they pull hammy faces, and roll their eyes. They chivvy, and cajole and argue. Most amazingly of all, at least for an outsider, they make no concessions to Mary's age when it comes to propriety; and she seems not to demand it. Never before have I discussed oral sex in front of a 90-year-old lady, let alone the oral sex enjoyed by her husband with another man; and I do not believe I ever will again. Here, though, it seems almost to be expected. Certainly, no one notices my blushes. The Cheevers, with gusto, and a certain amount of bravery, still like to squeeze their father's life until the pips fly out. I can't quite get over it.

Ben, too, loves Bailey's book. "He makes him into a hero, without distorting the quite ghastly facts." Did he learn anything from it? "Oh, yes! The facts, the sordid facts and the glorious facts, were available to me already. But he's presented a pretty accurate picture. When Daddy was alive, he was always changing everything. We were in a wonderful house! We were in a terrible house! So and so was his friend! So and so was despicable! I was his beloved son! I was a terrible embarrassment! It was very confusing. Blake has plotted that out."

Was reading it painful? "The painful experience in this process was reading journals. One of the most hurtful things for all of us is that we're almost never in them. You're actually relieved when you appear in them as a disappointment!"

Cheever was forever on at Susan about her weight; he wanted a pretty slip of a daughter, and thought her too greedy. But perhaps Ben had it worse. Cheever would complain in his journal that his elder son was effeminate, and to his face would tell him: "Speak like a man!" and "You laugh like a woman!" There was a time, Ben tells me, when he began to wonder whether he was, in fact, gay, and only acting heterosexual to please his father. Just to cap it all, it was to Ben that his father came out two weeks before his death, in a telephone call to Ben's then office at Reader's Digest. "What I wanted to tell you," he said, bluntly, "is that your father has had his cock sucked by quite a few disreputable characters…"

Does this mean that Ben hadn't, until that moment, realised what Max was to his father? "No, I hadn't. In fact, I remember Max flirting with me a little, and I was shocked; I thought Daddy would be horrified if he knew Max was a homosexual. But I think actual knowledge follows intellectual knowledge. My father told me that, but I didn't really… realise it until some time afterwards. It was upsetting but it wasn't as upsetting as being screamed at when you're a little boy for being effeminate. I've had to [over the years] reorganise a lot, and to some extent I'm still involved in that process. But this [the biography] is a story I can live with. Daddy has redeeming values. He was so funny."

Has it been hard, being Benjamin Cheever? "Yes and no. I was interested in being a writer, and I didn't like people telling me that they would have expected something better from John Cheever's son. That was tough. My first novel got turned down by lots of people, and no one could believe that. I'm sure there are lots of people who feel, with some confidence, that they would be a lot better a writer than me if they had my name. Everybody has a father; everybody has a psychic load. But I'm also lucky. In my attempts to figure him out, I have all these documents, and they're pretty well written, too. You're exactly right, though, to think that I had my ups and downs with him, even after he died. Sometimes I'd think: boy, he was a hero! He overcame all these terrible things. But then, other times, I'd think: boy, what a prick! He'd destroy every-thing just so he could get a drink, just so he could get blown.

"We all construct our own sense of righteousness, and I feel strongly that, as lonely as you were, you didn't sit down next to the first available woman or man on the train and try to… you know. This is my second marriage but it's been 27 years."

Does he think that Cheever would have shared a home with – or attempted to share a home with – Max had he lived? "I don't think Max would have been that important, had he lived. He was always a very fickle man. He would have had another boyfriend."

Through all this, Mary, who has not read the book ("I guess I have to… but there's nothing about me in it, is there?"), is mostly silent. Occasionally, though, she interjects. "He was an egotist!" she cries, when Ben describes his and Susan's hurtful absence in Cheever's journals. When I ask her, she tells me that she always knew, deep down, what her husband was. In Bailey's book, she says: "I sensed that he wasn't entirely masculine." To me, she says, more comically: "He was both!" So what attracted her to him? "His overcoat was too big, and I felt sorry for him." Was he handsome? "In a way, yes. He was funny. He made me laugh. His fault was to care about class, and money. He admired the life of the rich. He wanted a good life. That was what attracted him to me. I had a family. He had no family. Only a brother."

Did she think about leaving him? "Oh, yes. Quite often. But I couldn't leave the children, and how could I have supported them?" Did she miss him after he was gone? "Yes! I lived with him all my life. We didn't always get on badly."

"You were very important to him, as someone to adore, and someone to despise," says Ben, not softly but baldly, as if this were the most obvious fact in the world. "I used to tell myself that," says Mary. Her mouth is slightly twisted with age, so that the words pour out of one side of it, without any spaces in between them. "His whole life was about writing, and I believed in what he was doing, and I wanted to support that. I give myself credit for working at my marriage. More people should try that. I don't think he would have lived as long [without me]. I kept him alive. I give myself credit for that, too. And now Cheever is read all over the world, in languages I've never heard of. I couldn't still live in this house if people weren't buying Cheever."

She is right about this. But still, they do not buy enough. More than 25 years after his death, The Stories of John Cheever sells only about 5,000 copies a year in the US; Falconer and The Wapshot Chronicle have long struggled to stay in print at all, though they received a boost earlier this year when the Library of America – the closest America has to an official canon – reissued all the novels, together with most of the stories, in two volumes, with new introductions by Blake Bailey. (In the UK, to coincide with the British publication of Bailey's biography, Vintage is to reissue the stories, novels, journals and letters with new introductions by, among others, Jay McInerney and Hanif Kureishi). Nor – who knows why? – is he much taught in universities.

How can this be? It is unfathomable, especially in the case of the stories. They are so very beautiful, and singular. Cheever has all the dash of Scott Fitzgerald – an evanescence that calls to mind fine, cold champagne – but he combines it miraculously with a desolate modernism that is all his own. "Cheever's characters are adult, full of adult darkness, corruption, and confusion," wrote John Updike in a review of Bailey's biography he must have written shortly before he [Updike] died. "They are desirous, conflicted, alone, adrift… His errant protagonists move, in their fragile suburban simulacra of paradise, from one island of momentary happiness to the imperilled next."

But perhaps this is too bleak a reading. The biography got poor Updike down. After we finish talking, Benjamin drops me at the station so I can get the train back into New York. Waiting on the platform, I choose a story of Cheever's that seems especially appropriate, "The Five-Forty-Eight". The station is very quiet but the story is exactly the opposite. A businessman is accosted on the train, at gunpoint, by his former secretary, Miss Dent. I finish it just as my own train arrives; I close the book at the precise moment that it pulls into the station. And as it does, I think of something Susan said to me on our drive. "My father is one of those writers who causes a shift in your vision," she told me. "When you look up, the world appears a little different."

A life in literature: Cheever's work

John Cheever wrote hundreds of short stories during his 50-year writing career, and novels including The Wapshot Chronicle, The Wapshot Scandal, Bullet Park and Falconer. He had a long and fruitful relationship with the New Yorker, which ran 121 of his stories. His collected stories stayed on the New York Times bestseller list for six months and won the Pulitzer prize for fiction in 1979. Here is Rachel Cooke's best of Cheever…

The Stories of John Cheever (1978)

If you only pick up one, let this be it. "A page of good prose remains invincible," said Cheever, and here is the proof. Strange, glittering and dark stories of suburban life, among them "Goodbye, My Brother", "The Housebreaker of Shady Hill", "The Sorrows of Gin" and "The Five-Forty-Eight".

The Wapshot Chronicle (1957)

Cheever's first novel, an episodic and funny account of the Wapshot family, who live in a New England fishing village, St Botolph's.

Falconer (1977)

Cheever's last novel and, for some, his masterpiece. It tells the story of Ezekiel Farragut, a university professor and drug addict who, while serving a prison sentence for the murder of his brother, begins an affair with another prisoner.

The Letters of John Cheever (1988)

Edited by his son, Benjamin, Cheever's letters gave the world its first glimpse of his inner torment. But they also convey the competitive agony of the writing life (correspondents include Saul Bellow and John Updike), and more than a few good jokes.

The Journals of John Cheever (1991)

Brutal, sad, shocking, honest: Cheever's diaries are as gripping – and about as long – as those of Pepys. Did he want them published? His biographer, Blake Bailey, and his children, who auctioned them after his death, think he did.