Research over the years

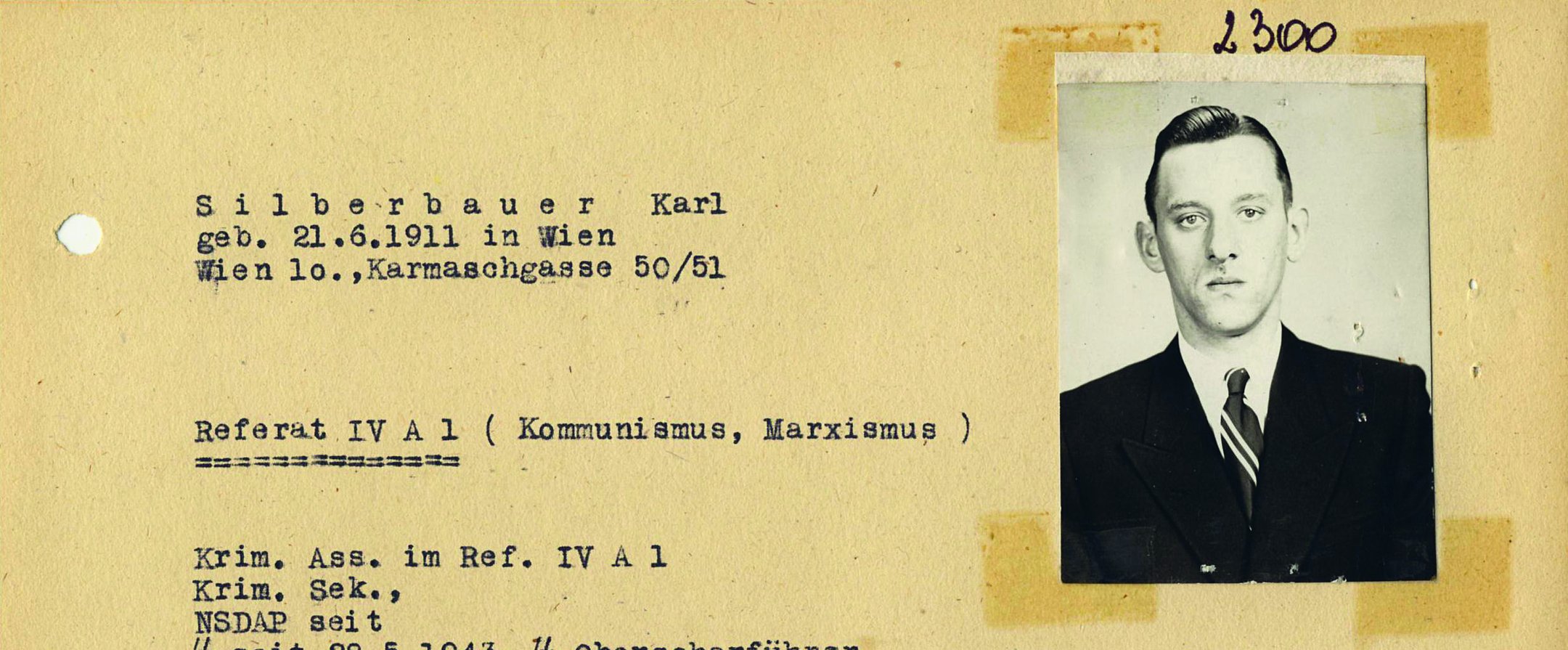

Explanations for the discovery are mainly based on testimonies, because no documents about the raid on the Secret Annex have been preserved. For a long time, betrayal was considered to be the reason for the arrest of the people in hiding, but the focus is shifting, as there are several other options.

The subject is still being researched. For instance, the Anne Frank House in 2016 reinvestigated the raid, and in 2017 a former FBI officer announced that he would be looking for the possible traitor of the people in hiding with the help of an international cold case team and new technology. On 17 January 2022 the cold case team presented their findings. We question several elements of the investigation: read our statement. In that statement we indicated the need for further research.