After the coronation of Jagiełło, Jadwiga was still formally King, and not just the wife of the monarch. As she matured, she increasingly often took the initiative in matters of the state and, in the final years of her life, was an independent politician, able to effectively negotiate with neighbours and set them tough conditions. Jadwiga went down in history as a founder of churches, monasteries, a patroness of intellectuals, and protector of the poor, the weak, and the abandoned – says Prof. Tomasz Graff.

Nowadays, many Polish historians choose the 20th century as the main object of their research. Yet you, Professor, choose to focus on the Middle Ages, including Queen Jadwiga, who ruled the Polish Crown at the end of the 14th century. Why? What intrigued you about her?

Since my student days, I have been fascinated by the Middle Ages and the early modernity. Jadwiga (Hedwig) of Anjou, on the other hand, has been attracting the attention of researchers for generations owing to her uniqueness – after all, she was simultaneously the King and Jagiełło’s (Jogaila’s) wife, a holy woman, a founder, and patroness. Her life is also the story of the beginnings of the Polish-Lithuanian union, the common but difficult path of Poland and Lithuania towards greatness. I have always seen in her both a pious woman, full of dilemmas and pain, trying to cope with difficulties in her private life, and an extremely effective politician. This mixture has long since intrigued me.

Jadwiga came from the Capetian (to be precise: Anjou) family, which is generally associated with the history of France: the Capetians included such monumental figures as Hugh Capet and Louis IX the Saint. How did it happen that the descendants of the kings of France took over the rule in the Kingdom of Poland?

Jadwiga had the blood of many dynasties in her veins, not only the Capetians, but also the Byzantine Emperors and the Piasts. After all, she was the granddaughter of Elisabeth of Poland, Queen of Hungary on her father’s side. In fact, it would be more difficult to name a dynasty of that time to which she was unrelated… Her father – Louis I of Hungary – took the Polish throne in 1370, according to the succession treaties concluded with Casimir the Great. The last king of Poland from the Piast dynasty hoped that these agreements would work in his family’s favour. It happened otherwise, however, as he eventually did not live to see a legitimate male descendant. At the end of his life, he adopted his grandson, Casimir IV, Duke of Pomerania. For Louis, such a solution meant the failure of his appetites for the throne of Poland. Therefore, he rescinded Casimir’s bestowals, and crowned himself very quickly. I should add that not everyone rejoiced at the assumption of power by the new ruler.

Were there just sighs in Poland, or were more decisive actions taken?

Yes, there were attempts to overthrow the Angevin succession to the Polish throne. One of the oppositionists, the famous chronicler and archdeacon of Gniezno Jan of Czarnków, was even caught attempting to steal insignia from the tomb of Casimir the Great, which were likely to be used for the coronation of one of Louis’ rivals to the Polish throne. For Jan, this ended in a sentence of banishment, and the confiscation of his property. On the positive side, however, the exile wrote a chronicle in which he vividly described the Angevin rule, criticising Louis, his mother Elisabeth, and their supporters. Another thing is that, at times, this criticism turned into slander.

Do we know anything about Jadwiga’s childhood?

We do know that she received a thorough education – she could read and write. She learnt several languages (Hungarian, Latin, and German, possibly Czech; later she learnt Polish). She knew court dances, music, and etiquette, and of course the Holy Scriptures, likely the lives of saints, mystics such as St Catherine of Siena, and secular literature from the circle of knightly epics. Louis I of Hungary personally cared about the education of his daughters, recommending them to learn Latin, and become acquainted with Hungarian culture. She was greatly influenced by her pious grandmother Elisabeth of Poland, one of the most outstanding women of the 14th century. It is known that the Hungarian court – unlike many others – was characterised by great piety. The Angevins attended mass daily, and were well known for their acts of charity and numerous foundations. They befriended and cared for Franciscans, and ensured a good family atmosphere among their relatives.

Jadwiga also stayed in Vienna for some time. Why?

It was due to matrimonial plans to marry her off to William the Courteous. She was sent to Vienna to become familiar with the local court and culture. There, she was put under the care of Albrecht III, who was the brother of her future father-in-law, Leopold III of Austria. Albrecht was fond of books and simultaneously famous for his piety. He showed Jadwiga monasteries and churches, places of pilgrimage, and relics of saints. It was likely that William’s mother had some influence on the Queen. At the Habsburg court, Jadwiga must have heard stories about brave and pious knights, as well as learning about the art of the popular court poet Peter Suchenwirt. It was thanks to him that she heard stories about the terrifying Lithuanians, because Peter had accompanied Albrecht III on an expedition to those regions, and Lithuania at that time, according to Teutonic propaganda, was a wild country, to which one could organise further expeditions with impunity, under the pretext of crusades. Perhaps it was then that she first heard about Jogaila, the new Grand Duke of Lithuania. However, in 1379, Jadwiga returned from Vienna to Buda owing to the death of her sister Catherine.

It was not typical for the Polish Crown to be ruled by a woman. In what circumstances did Jadwiga become monarch?

As we know, at the convention in Kassa (1374), the Polish nobility agreed to the female succession of the daughters of Louis I of Anjou in exchange for the issue of a privilege. Jan of Czarnków, whom I have already mentioned, was a great opponent of such solution. The king had three daughters: Catherine, Mary, and the youngest, Jadwiga. In the original plans, Jadwiga was not destined for the Polish throne. It was Maria who was to become the Polish queen, and rule together with her husband, Sigismund of Luxemburg. However, when, after the death of Louis, Hungarians chose Mary as their ruler, the prospect of ruling in Poland opened up for Jadwiga.

So, did her succession go smoothly? Or did bargains take place with Polish magnates?

The Poles made a condition: in spite of her young age, the heir to the crown should come to Krakow quickly and, after the coronation, she should stay in Poland permanently. However, Elisabeth of Bosnia procrastinated for a long time, and the negotiations strained the patience of Poles who, interestingly, initially accepted the possibility of Jadwiga sitting on the Polish throne together with William the Courteous. On the other hand, some lords, led by the Archbishop of Gniezno, Bodzęta, hailed Siemowit IV, a Masovian Piast, as King (1383). Elisabeth, forced by the circumstances, finally sent her daughter to Poland two years after her husband’s death. It should be added that Siemowit did not resign from the Polish throne for some time, and some researchers believe the account by Jan of Czarnków to be credible, according to which the prince even wanted to kidnap Jadwiga, and force her into marriage and a joint coronation.

When she was crowned – which took place in 1384 – she was very young, about ten years old. What was it like to exercise power with such a young ruler?

Jadwiga was prepared to rule already as a little girl. However, we should remember that, in a foreign country, in the beginning, she was dependent on her closest advisors, who were mainly lords of Lesser Poland. These, in turn, wished to pursue not only the interests of the Crown as such, but also their own political agendas, which they incidentally identified with the former. Thus, in the first years of her reign, as a child, she was not a very independent ruler.

Did Jadwiga’s role as a ruler increase with her growing up?

Yes, along with her maturing and the changing dynamics of the political situation, particularly during the first years following the coronation of Jagiełło. At that time, her political role and independence were increasingly visible in the light of the sources. She learnt how to select capable advisors, how to creatively, together with her husband, fill church posts in Poland and Lithuania with trusted people, and how to properly shape relations with the Holy See, weakened at the time by the ongoing schism. She was instrumental in the Christianisation of Lithuania (1387). The bishopric of Vilnius was baptised and established at that time, although she likely never came to Lithuania herself. She generally got on well with Vytautas, who had great ambitions, and with Jagiełło’s rival brother Skirgaila. She negotiated firmly with the Teutonic Knights, or with the constantly troublesome Vladislaus of Opole, and led an armed expedition that reunited Red Ruthenia with Poland (1387). At that time, the royal couple were also paid homage by the Moldavian lord Peter. These successes were possible thanks to the skills she was gradually acquiring. From the first years of her reign, however, everyone admired not only her piety and education, but also her great maturity, rarely seen at such a young age.

At first, it was planned that Jadwiga would marry William the Courteous, the Duke of Austria. In the end, however, she married the Lithuanian Duke Jogaila, later baptised with the name Władysław. How did this happen?

On 18 August 1374, when Jadwiga was less than a year old, Leopold III of Austria asked Louis I of Hungary for her hand in marriage for his son William. In those days, dynastic marriages were part of court policy, and were arranged even in infancy. However, when Jadwiga ascended to the Polish throne, the Polish lords already had other plans, and they were connected with Lithuania and its Grand Duke Jogaila, which was realised in the Union of Krewo (1385). Therefore, they did everything to prevent the consummation of Jadwiga’s union with William, even though he did appear in Krakow, and hoped to become the Polish king thanks to this. Disregarded by the Polish lords, the Habsburg had to lose out to the far-reaching plans of the Polish lords, which eventually led Jadwiga to marry the newly baptised Jagiełło on 18 February 1386. Before that, the Queen had publicly revoked her relationship with William.

Did William accept the rejection?

No – he even launched a lawsuit in which he was supported by the Teutonic Knights. In this way, for years, rumours slandering Jadwiga were spread across European courts, stating that her marriage with William had allegedly been consummated. It was also added that, through her marriage with Jagiełło, she had become a bigamist. These were ill-founded, especially since the Poles, in their own political interest, had simply made sure that the marriage of Jadwiga and William had not been consummated.

How did that marriage influence Jadwiga’s position as a monarch?

After the coronation of Jagiełło, Jadwiga was still formally King, and not just the wife of the monarch. As she matured, she increasingly often took the initiative in matters of the state and, in the final years of her life, was an independent politician, able to effectively negotiate with neighbours and set them tough conditions. Significantly, outwardly she and her husband generally demonstrated a consensual position on political and church matters. In her private life, she suffered much pain caused by the loss of loved ones. She lost her father early, her mother was murdered, and her sister lost her life after falling from a horse.

Are we able to judge how happy the marriage of Jadwiga and Jagiełło was?

A shadow over the marriage of Jadwiga and Jagiełło was certainly cast by the inability to get pregnant for many years, which was then commonly blamed on women. Differences in character, culture, and upbringing between her and Władysław Jagiełło were also significant. Certainly, Jadwiga was more attracted to Orthodox culture and art, which he knew still from Lithuanian times. Jadwiga’s relations with her husband became warmer when Jagiełło discovered that Jadwiga was pregnant. Interestingly, in her correspondence with popes, Jadwiga always emphasised her deep love for her husband and the legitimacy of their marriage. She tried to support her husband also in church politics. Together, they asked Boniface IX for permission to establish a Faculty of Theology, which resulted in the papal bull of 1397, in which the pope agreed to open this most prestigious university faculty in the Middle Ages in Krakow.

Jadwiga is also known as a patroness of culture. What can we say about her activity in this field?

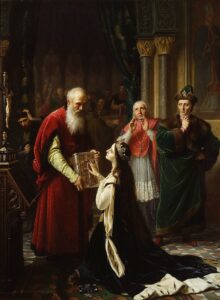

The Queen went down in history as a founder of churches, monasteries, a patroness of intellectuals, and protector of the poor, the weak, and the abandoned. Even her contemporaries were impressed by the breadth of her activity in this area. It was for her that De vita activa et contemplativa, largely expressing her spirituality, was written by the Dominican Henry Bitterfeld. She also commissioned an extraordinary monument, the Florian Psalter, written in Polish, German and Latin. It is known that she asked for translations into Polish of saints’ lives, writings of the Fathers of the Church, fragments of the Bible, and other works. In Krakow, together with her husband, she founded, for instance, the Carmelite Monastery in Piasek, and also launched the process of bringing the Lateran canons to the district of Kazimierz, founded the college of Psalterists on Wawel Hill, and is said to have personally embroidered pearls onto the ornamental belt of Krakow bishops, known as the Rational.

Jadwiga died at a young age – about 25. What caused her premature death?

On 22 June 1399, Jadwiga gave birth to a daughter, Elisabeth Boniface. Pope Boniface IX himself agreed to be her godfather, after whom she received her second name. Unfortunately, the Queen’s daughter died on 13 July and, four days later, Jadwiga also died due to postpartum complications. Her death saddened most of the inhabitants of the kingdom. She was buried two days after her death, together with her daughter. A wonderful speech at her funeral was delivered by her advisor, Stanisław of Skarbimierz, the future first rector of the renewed University of Krakow: ‘Our cry rose up to heaven, so that the Lord God would preserve this adornment of the Polish Kingdom, this mainstay of the state order, this unique jewel, this solace for widows, this comfort for the destitute, this help for the oppressed, this respect for the dignitaries of the Church, this refuge for priests, this strengthening of peace, this testimony and protection of God’s law.’

Jadwiga occupies an important position in Polish historiography and culture. What can we say about this phenomenon?

It appears to me that no Polish ruler likely enjoys such popularity in historiography. Many historians have undertaken to write her biography, and still one has the impression that not everything has been said about her. A crowned King of Poland, Jadwiga fascinates not only researchers, but also many ordinary people who are attracted by her personality and spirituality. Dozens, if not hundreds of schools, institutions and streets bear her name. We can also see Jadwiga on the pedestals of monuments, not only in Poland, but also abroad, e.g. in her homeland of Hungary. Certainly, Pope John Paul II, who canonised her in 1997 at the Błonia meadow in Krakow, could take great credit for propagating her cult.

Which of Jadwiga’s features can inspire us in the 21st century?

I believe that anyone who becomes better acquainted with her biography can find something that appeals to them in particular. For some, it will be her deep faith, combining vita activa and vita contemplativa. For others, it will be her kindness towards others, her fundraising and charitable activities. Others may see her as a patroness of women expecting children, and an inspiration to conversion, even at a ripe old age, like her husband Jagiełło. In Kraków, we also remember her contribution to the establishment of the Faculty of Theology and the renewal of Krakow University, to which she donated her valuables in her last will and testament. The number of institutions and schools that have chosen Jadwiga as their patron saint following her canonisation has grown exponentially; we can see her monuments and portraits not only in Poland, but also abroad, e.g. in Hungary. This is sufficient proof that, after several hundred years, the Holy Queen Jadwiga continues to inspire and fascinate subsequent generations with her life, not only in Poland, but across the world.

Interviewer: Łukasz Kożuchowski (Polish History Museum)