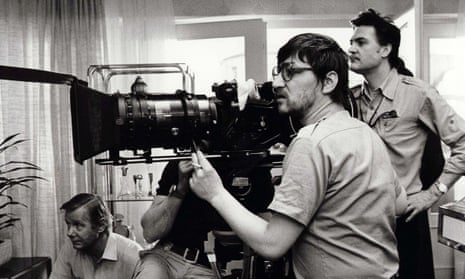

Rainer Werner Fassbinder is receiving belated recognition. Sixteen years after his death the bitter genius of German cinema is being celebrated in a mammoth two-month festival at the National Film Theatre. The NFT programme duly pays tribute to the Fassbinder Foundation and its director, his wife and editor Juliane Lorenz, without whom it would have been impossible to show his 44 films.

Only one problem, says Ingrid Caven: Lorenz was never his wife. Caven, who starred in many of his early films, indisputably was. She says the reference to Lorenz as Fassbinder's wife is 'ridiculous', and talks of the sickness of those who 'use cadavers for their own purposes'. She believes her role and marriage are being written out of the official biography. Although divorced in 1972, Caven still signs herself Fassbinder and kept his name on her passport.

Lorenz is dismissive of the criticisms. She says Caven is 'a woman I adored and defended' before sticking the boot in. 'Now she's getting crazy because she doesn't want to accept that I was with him. There were others as well. She wants to be the only woman he ever slept with. She is like an old widow who doesn't accept that the man developed.' As for the charge of claiming to be his wife, she repeats the account in her book Chaos As Usual, of a beautiful 'mock ceremony' in Fort Lauderdale in 1979 without the blood test to make it a legal marriage. She says Fassbinder treated her 'like a woman and as his wife'.

There is something horribly ironic about the women's fight to stake a claim on Fassbinder, to empower themselves by proxy as 'the wife'. After all, this is the director whose films obsessively explored power struggles in relationships and the oppression of bourgeois culture - and never more so than in depicting the tyranny of marriage. Perhaps the most memorable thing Fassbinder's films have left us is an astonishing gallery of female characters, from the icy glamour of Maria Braun to the self-obsessive hysteria of Petra von Kant, to the middle-aged, working-class cleaner Emmy, who enrages her community when she has an affair with a Moroccan gastarbeiter in Fear Eats The Soul. The bisexual director's attitude to women was deeply ambivalent. He has been accused of misogyny, yet there is also fascination and empathy.

Fassbinder's personal relationships were riddled with violence and jealousy. Two of his lovers committed suicide: El Hedi Ben Salem, the male lead in Fear Eats The Soul, was whisked off to Morocco after a jealous stabbing frenzy in a Berlin bar and later hanged himself in a French jail; another male lover, Armin Meier, was found dead in Fassbinder's apartment a week after he comitted suicide. One of his actresses and lovers, Irm Hermann, claims she was physically abused.

Fassbinder's death, at the age of 37, from heart failure following a lethal cocktail of cocaine and sedatives, was also grist to the media mill. Though many claim he died of overwork, drugs had become a frequent tool for his breakneck production process, and some suggest he had exhausted his oeuvre and lost the will to live.

His chaotic personal life went back to his childhood and his relationship with his mother, Liselotte Eder. There were frequent separations, primarily through his mother's hospitalisation with tuberculosis. His father moved out when he was six and the household was anarchic, with frequent visitors, but, says Eder, in a 1982 interview in Christian Braad Thomsen's biography, little love or openness.

Fassbinder went on to cast Eder in his films, often in humilating roles such as the unforgiving mother in Effi Briest. She worked as his business manager from 1971-78 and set up the Fassbinder Foundation in 1986 to protect his legacy. Before her death in 1993, she handed over the Foundation to Lorenz.

Caven met Fassbinder during the days of the collective Action Theatre. They were united by sixties utopian idealism. The ghost of Nazism haunted a generation who determined to do things differently. Personal relationships and working practices were both up for grabs. Caven describes Fassbinder as 'an intellectual who approached the erotic like a street hawker'.

Fassbinder worked with a loyal clique with whom he was frequently intimate. By 1969 they lived in a commune, jokingly described by one friend as 'Sodom and Gomorrah'. Rows were frequent and furious. Yet creativity thrived. Fassbinder's working method was fast and intensive - he made 10 films between 1969 and 1970. He worked in a hierarchy that kept actors struggling for status and attention. Dependency and jealousy flourished. His tactics included insults to create the rage and humiliation crucial to a role. He also encouraged no-holds-barred truth games.

Fassbinder married Caven in 1970. It seems surprising that a filmmaker so critical of bourgeois institutions should marry at all. Caven explains that, despite his politics, Fassbinder came from a 'middle-class, intellectual family', and had no desire to break with his background. He played the traditional husband and could be intensely jealous. On the other hand, their social life was wild, with celebrations every day. She says he was funny, with a passion for life.

There is little lightness in the films of this period, which dissect the dynamics of close relationships. Fassbinder said that women knew how 'to make use of their oppression as an effective instrument of terror'. He illustrated this in the character of Irmgard in the Merchant Of Four Seasons (1971). Irmgard is frantically jealous of her husband Hans, who stays out late and beats her. Yet Irmgard uses her status as victim and swiftly turns the tables on her weakened husband, taking a casual lover as he lies sick in hospital.

In The Bitter Tears Of Petra Von Kant, the power struggle is more pronounced. Petra, a recently divorced, wealthy fashion designer, takes up with Karin, a younger, working-class girl - perhaps a parallel to Fassbinder's own infatuations with men who were economically his inferior. Karin uses the relationship to further her career. After Karin leaves her, Petra indulges hysterically in bouts of self-aggrandisement, melancholy and vicious truth-telling. She seeks solace in her silent slave/employee, Marlene. At the first sniff of kindness Marlene leaves to look for someone else to dominate her.

By 1972 the marriage was over. Fassbinder's working methods, his jealousy of Caven's independent career (she is a charismatic chanteuse), and drugs all contributed to its breakdown. Afterwards they got on better than ever, and he pleaded with her to remarry.

The strongest condemnations of marriage come in the films following this break up. Effi Briest, Fassbinder's adaptation of Fontane's novel, explores the stifling marriage between a young woman and a cold, older man of strict principles. Effi (Hanna Schygulla) is broken by the condemnation of society, including her mother, after her affair with Major Crampas. Schygulla and Fassbinder fell out over the role and she did not work with him again for five years. Like other actresses she felt the part constricted her 'like a corset'.

Martha, his update of Effi Briest, is an even bleaker portrait of marriage. Martha is a sexually repressed 30-year-old woman who marries Helmuth. He sadistically 'educates' her to conform to his view of an ideal wife. Her resistance is weak, and finally pathological; she is crippled in a car crash as she tries to escape.

Margit Carstensen, who played Martha, has said Fassbinder 'was the first person who wanted to see me the way I was. He made me aware that the character I was playing was also about myself'. But there was a downside. 'There comes a point when one feels reduced to a few specific traits and it is humiliating to be used in this reduced state.' Like Schygulla and Hermann, she needed a break. 'He provoked and tormented me daily with snide remarks. What he demanded was love, or let us say, voluntary submission'.' Caven dismisses Fassbinder's alleged cruelty as 'childlike'. She says his collaborators understood this and forgave him. And indeed for many the experience of working with Fassbinder bordered on love. Others, like Schygulla, kept their distance. 'There was always this fear of being exposed or learning more about yourself than you wanted to know,' she says. He had something of a cougar, that watchful tension of his eyes.' But other evidence is not so forgiving or forgetful. Germany In Autumn (1977-78), a documentary response to terrorism, shows the psychological cruelty to Armin Meier, in a series of staged arguments between him and Fassbinder. Fassbinder met Lorenz in 1976 when she was 19, during the crisis of this relationship. They became intimate after Meier's suicide, in 1978. In his last years Fassbinder had become calmer, Lorenz says. He no longer had sex with men and he produced some of his most popular and mature work, including the 15-hour TV masterpiece, Berlin Alexanderplatz. Braad Thomsen claims they were drifting apart in the last year, but she denies it.

The one thing Caven and Lorenz are agreed on is that the films are more important than their conflict. They both say they refuse to fuel the gossip surrounding him - while doing just that. Lorenz says the stories are recycled and irrelevant, and Caven uses the word 'dirty'.

They emphasise the importance of German identity to his work. Caven says that 'In his films, and in his life, until the most tearing and aggressive moments, he was looking for a form, for a new beauty and joy based on the ruins of a Germany drained of life and soul.' As she discusses Fassbinder's death, she is hesitant, regretful. She describes the relationship as the most intimate rapport possible, and quotes Fassbinder from a 1978 TV interview: 'Of all the actresses and actors I've been involved with Ingrid is the least willing to let herself be reduced to being an actress... if people say there are elective affinities in life, I'd say that's who matters to me most'.' Lorenz was devastated by his death. 'For 10 years I was lost. He was a human being who was very much aware. There was a discipline, a world he described - and his intelligence, his incredible humanity. He was like a big brother... There was love. He educated me. He awakened me. He always supported me. In 100 years' time', she says, 'no one will remember our quarrels. His work, in its entirety reflects a country's development. It describes a Germany that no longer exists.' Both women are passionate about his films and staunch in their loyalty to his memory. Both allocate themselves a central role in the drama of his life. They are equally critical of the other. One is reminded of Veronika Voss. A sportswriter (Robert Krohn) befriends fading fifties movie star Voss (Rosel Zech), who has drifted into addiction. Krohn is as much a prisoner of her artificial glamour as she is of the illusion of stardom. Voss dies from an overdose. At her farewell party she sings Memories Are Made Of This, as the camera circles round her in a sweeping pan of greenhouse windows from which she is observed. The jaunty tune, the husky, ironic cabaret performance, the distant faces looking in on her and framed by window bars, convey a bitter sadness. The illusionist world of film has been insufficient to satisfy her and she drifts alone towards annihilation, leaving those who loved her to mourn.

The NFT Fassbinder season plays throughout January and February