‘My aunt might have betrayed Anne Frank,’ writes son of Secret Annex helper

Writer Joop van Wijk has spent years piecing together his mysterious Aunt Nelly’s wartime activities, cutting through lies that concealed her Nazi collaborator past

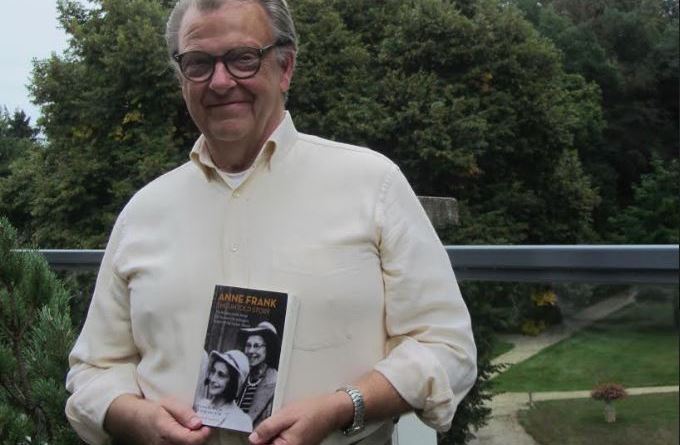

More than three decades after Elisabeth “Bep” Voskuijl’s death, her son co-authored a biography of the least-known among the Dutch resisters who hid Anne Frank and other Jews during the Holocaust.

Although Joop van Wijk’s book follows the course of his mother’s life, the suspense swirls around his late aunt Nelly, Voskuijl’s sister. Specifically, the author believes Nelly was involved in the betrayal of the so-called “Secret Annex” Jews, including the iconic teenage diarist.

Born in 1949, Van Wijk remembers a childhood shrouded in mystery about what Nelly did during the war. While his mother — referred to as “Elli Vossen” in The Diary of Anne Frank — risked her life to hide eight Jews, his aunt had behaved shamefully during the occupation of the Netherlands, it was whispered.

Co-authored by Belgian journalist Jeroen De Bruyn, Van Wijk’s book is called, “Anne Frank: The Untold Story,” with the subtitle, “The hidden truth about Elli Vossen, the youngest helper of the Secret Annex.” (As 15-year old Anne refined her diary with an eye toward eventual publication, “Elli Vossen” was the pseudonym she gave to Bep.)

Recently translated into English, Van Wijk’s family account adds what he calls “a remarkable name” to the list of people suspected of betraying the “Secret Annex” nearly 75 years ago: his mother’s sister.

Since 2017, Van Wijk has been interviewed several times by members of an international forensics team looking into the “cold case” of the betrayal, he told The Times of Israel. One of the reasons his aunt has been overlooked by past investigators, believes Van Wijk, involves his family’s darkest secret.

‘Nelly did it with krauts’

Bep Voskuijl was only 18 when she started working for the spice and jam company owned by Otto Frank. Within five years, she was “illegally” buying bread and milk for her Jewish friends in hiding and — just as important — giving them her sought-after company.

Among other activities, the Frank sisters took correspondence courses in Voskuijl’s name, and the administrative assistant put aside filing for the sisters to do at night. Anne’s relationship with her sister Margot was standoffish, and Voskuijl helped fill some of the gap between them.

Although Miep Gies is the best-remembered of the Dutch “helpers,” Voskuijl was the closest to Anne in age and temperament. Anne often wrote about “good-natured Bep” in her diary, including happenings in the large Voskuijl family of eight siblings.

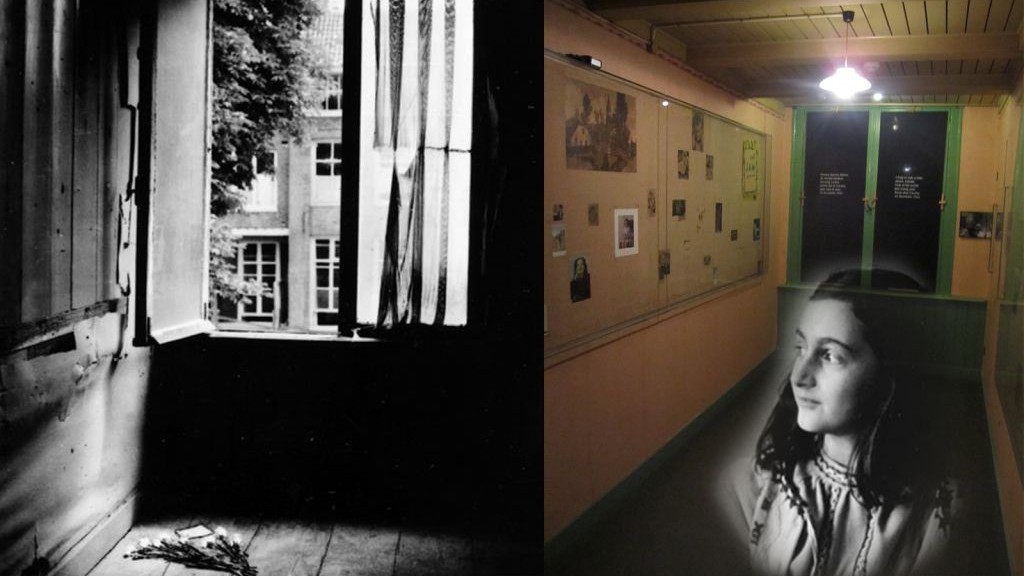

Voskuijl’s father, Johan, was also in on the secret of the Jews in hiding. Not only did he build the famous swinging bookcase to conceal the hiding place, but he served as an unofficial watchman over the annex through his employment in the warehouse below.

In addition to Johan Voskuijl’s involvement, another of the Voskuijl sisters sewed clothes for the Jews in hiding, making the effort a family affair.

There was one sister, however, who took a different path, Van Wijk was told growing up.

“Nelly did it with krauts,” the author’s father slipped at the table from time to time.

Although he heard about Nelly’s romantic liaisons with Germans while growing up, Van Wijk was never told about his aunt’s role as a Nazi collaborator. Only when he began research for the book in 2010 was the long-time marketing professional able to locate documents that contradict the family backstory on Nelly.

“My mother had lots of troubles with Nelly during the war and after the war,” Van Wijk told The Times of Israel. “This should be part of her biography.”

‘Just go to your Jews!’

Even during the early days of the war, the Voskuijl family faced trouble with Nelly. Not only was she carousing with German soldiers, but Nelly’s rowdy behavior earned her a stint in police custody. Later, when father Johan Voskuijl and sister Bep were involved in hiding Jews on the Prinsengracht, Nelly was working for the Nazis across town.

In her diary, Anne Frank wrote about Nelly on several occasions. Specifically, Anne referred to the “troubles” brought upon the Voskuijl family by Nelly, and that the young woman was “often away from home.”

During his research for the book, Van Wijk learned that Nelly did far more than engage in flirtations with German soldiers. His aunt’s past as a Nazi collaborator, as well as her whereabouts during a key part of the hiding period, had been covered up by the family.

“Nelly didn’t just engage in an adolescent relationship with a soldier — it went far beyond that,” wrote Van Wijk.

In the middle of war, Nelly moved to Austria with a Nazi officer, only to have the relationship fall apart. Van Wijk had always been told Nelly did not return to the Netherlands until the end of 1944 or early in 1945 — after the betrayal of the annex. However, because Anne wrote about Nelly’s collaboration with the Nazis in the original version of her her diary, the authors proved that Nelly returned to Amsterdam in 1943.

Around the time of Nelly’s return, her relations with the family “strongly deteriorated,” wrote Van Wijk, including Johan Voskuijl physically beating his daughter. This “deterioration” took place around the period in which a call was made to Gestapo headquarters by “a young woman” — it was later claimed — to inform on the Frank family’s hiding place.

In Van Wijk’s assessment, there is no doubt Nelly knew about the Jews in hiding. After all, one of her sisters and her father joined the high-risk effort of hiding, feeding, and sustaining eight Jewish fugitives. The author’s suspicions were deepened during interviews he conducted for the biography.

“Nelly knew that Bep and her father were helping Jews. That’s obvious,” said Bertus Hulsman, who was the wartime boyfriend of Voskuijl and sometimes mentioned in the diary.

After tracking down Hulsman for the book, Van Wijk learned of a heated conversation between Nelly and other members of the Voskuijl family during the hiding period. The encounter ended with Nelly shouting, “Just go to your Jews!”

‘Out of loyalty for my mother’

At the time of Bep Voskuijl’s death in 1983, she was the least known of the four Dutch resisters who helped hide Anne Frank. After discovering some of the family’s long-held secrets, Van Wijk now believes there is an unsettling reason behind his mother’s relative “anonymity” among the helpers.

In 1963, the SS officer who conducted the annex raid told investigators a “young woman” made the betrayal call. Previously, Voskuijl and others had placed suspicion on a disgruntled male warehouse employee, Willem van Maaren. Around the time of the investigation into the SS officer, Voskuijl ceased granting interviews, wrote Van Wijk.

In the author’s opinion, his mother had an internal conflict that led her to “opt for as little attention as possible, practically complete radio silence, from the beginning of the Sixties,” he wrote.

“[My mother] often lived in the past after the war and mulled over the split she found herself in: the loss of her Jewish loved ones from the Annex on the one hand, and her loyalty to her sister [Nelly] who had proven her services to the occupier on the other hand,” wrote Van Wijk.

Additionally, believes Van Wijk, Otto Frank either suspected or knew of Nelly Voskuijl’s role in the betrayal. After the war, Frank removed content from Anne’s diary regarding Nelly’s collaboration. One year before his death in 1980, Frank told an interviewer he believed “a woman” made the call to the Gestapo. Prior to that, Frank always said he did not want to know who betrayed his family.

“[Otto Frank] might have done this out of loyalty for my mother,” wrote Van Wijk.

‘The biography is my mission’

In Joop van Wijk’s psychological “diagnosis” of his late mother Bep Voskuijl, she spent her post-war life “being her own therapist” in a “kind of conversation with her alter ego. But soon, it proved she was unable to resolve things that way.”

One day during his youth, Van Wijk heard his mother sobbing in the bathroom. He found Voskuijl “in a desperate state” with “a mouthful of sleeping pills.” She made him keep the episode their secret, he wrote.

Among Voskuijl’s other secrets that her son came to know, the clandestine affection shared by his mother and Victor Kugler, one of the other “Secret Annex” helpers, fills a page of the book.

“Throughout the course of the hiding, Bep and Kugler had fallen in love, as Bep later confessed to her sister Diny with red cheeks,” wrote Van Wijk. “It made sense that two people who were constantly in each other’s vicinity and shared the role of helper of Jews, grew closer,” he wrote.

Kugler was a married man, and he never shared the secret of the hidden Jews with his wife, wrote Van Wijk. At one point, Kugler was prepared to end his marriage in order to move to South America with Voskuijl, but she did not want to wreck their marriage.

In the years following Nelly Voskuijl’s death in 2001, Van Wijk attempted to learn more about the relationship between his mother and his aunt from members of the large family. According to the author, he has mostly been met by cold shoulders.

“My sister and my oldest brother are still angry with me about the content of the book,” Van Wijk told The Times of Israel. “My aunt Willy [Nelly’s sister] was furious until she died in 2015, just before the publication,” he said.

Although he published his mother’s most intimate secrets, Van Wijk believes his book “would eventually have gained her approval, because she greatly upheld the truth,” he said. Tellingly, the book’s title in Dutch was, “Silent No More.”

“The biography is my mission,” said Van Wijk, who dedicated the book to Dutch resisters against Nazism. “It is my contribution to peace, understanding, respect, and above all loyalty to every human being.”

Are you relying on The Times of Israel for accurate and timely coverage right now? If so, please join The Times of Israel Community. For as little as $6/month, you will:

- Support our independent journalists who are working around the clock;

- Read ToI with a clear, ads-free experience on our site, apps and emails; and

- Gain access to exclusive content shared only with the ToI Community, including exclusive webinars with our reporters and weekly letters from founding editor David Horovitz.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel