Anthony Bourdain, who has taken his own life aged 61, will be remembered by most as one of the world’s first and most influential celebrity chefs. It’s an inadequate description.

Bourdain claimed he was a “competent line cook” rather than a chef during the two decades from 1978 in which he ran the kitchens of increasingly large New York restaurants. For much of that time, he was addicted to cocaine and heroin and moving among a semi-criminal demi-monde that characterised the restaurant scene before cooking became a fashionable career choice. He published two creditable, tight, crime novels set in kitchens – Bone in the Throat (1995) and Gone Bamboo (1997) – and also began contributing magazine articles. It was one of these, a piece for the New Yorker, Don’t Eat Before Reading This (1999), that formed the basis of his breakthrough book, the bestseller Kitchen Confidential (2000).

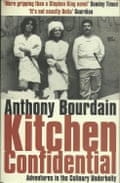

Kitchen Confidential hit us like Elvis. Both the UK and the US were on the edge of an explosive growth spurt in interest in food and, suddenly, here was a book that put everything in a new context. Food was sexy, chefs were cool … this was not about snotty wine-waiters in shiny suits and elderly Frenchmen in tall white hats. It was all about those three guys on the cover, a young Bourdain and two unidentified cooks on his shift. Leaning against the wall, out the back by the trash cans, grabbing a Lucky Strike during a lull in service. Sweaty bandanas, filthy aprons, T-shirts you could almost smell coming off the paper. They looked like Rimbaud, Che Guevara and Jesus on the cover of their debut album and readers lapped it up.

The book itself is a strange mashup. It is more a collection of essays than a solid narrative. It is said to have been rushed into print on the strength of the New Yorker piece, and some of it, in hindsight, feels like filler, but parts are inspired. For me it was a single passage that resonated most: the description of being the first guy on the line in the morning. Alone in the kitchen, a hangover and a double espresso from the still-warm La Marzocco machine, knocking up a scallion and chorizo omelette as you set up your station. It was beautiful. And when he was on form, Christ, could Bourdain weave words. Not pretentious, not the purple passages of food writers before him, the high prose of the refined connoisseur but the terse, full-auto linguistic firepower of a New Yorker – imagery like crime-scene photos, the flayed raw humour of a morgue attendant, the sort of one-liners a hitman drops as he pulls the trigger, and similes that would make Raymond Chandler eat his own pencils. For all the rock’n’roll, the easy, sleazy charm, the guy wrote like a poet and, as he got older, he just got better.

Perhaps the key turning point in Bourdain’s career followed the success of the book. He began working with the television producer Lydia Tenaglia, in a collaboration that couldn’t have been better timed. The Food Network TV channel was becoming more popular by the day and looking for new talent, broadcast-quality video was now achievable with a new generation of lightweight cameras, and Bourdain was working on a second book that combined food and travel.

A Cook’s Tour, broadcast in 2002, the year the book was published, was shot quickly with a tiny crew, entirely on location. Bourdain could immerse himself in a culture through its food, and the camera was there, hand-held, grainy and immediate to record the experience. There had never been anything like this. To an audience still expecting “stand-and-stir” cookery programmes, it looked like a combination of rockumentary and combat footage. And they loved it. More importantly, it put Bourdain in charge. He had managed to parlay the success of Kitchen Confidential into total control of his own TV output.

The first shows had alarming camera angles, dodgy cuts and lacunae in continuity where it looked as if the team had either run out of money or had to sleep off some monumental bender. Bourdain, whose dress sense was ever questionable, stalked the screen, in boilermaker sunglasses and a cap-sleeved T-shirt, like a gaunt, smashed Joe Strummer, swearing like a longshoreman, occasionally actually drunk. But he had made it there, to Bangkok, to Ho Chi Minh City, and he was going to consume it, without restraint, on our behalf. It seemed chaotic, shot from the hip, but already, he had adopted the commentary as a signature. Use of a voiceover narrator in traditional programme-making usually masks failure. It is a device to hold together insufficient, poorly planned or shot raw material. Here it gave Bourdain, the writer, space to get back to the edit suite and craft something brilliant. He stayed with this format, with little change, as the production values of his programmes improved, his audience grew and other broadcasters began paying more to host him.

What Bourdain did with the control he had gained was to develop and pioneer an entirely new form of early reality TV that freed him to immerse himself, scriptless, in the experiences he chose and communicate later with brilliant clarity. Bourdain is often compared to Hunter S Thompson for his narcotic intake and profanity, but there is a greater similarity with Thompson’s book Hell’s Angels, his more considered work of immersive New Journalism. As with Thompson, Bourdain’s willingness to throw himself into a situation and then write it up afterwards, balancing his writer’s experience against the bloodless objectivity of the professional journalist, leaves us with some of the most authentic and engaging stories.

Bourdain was born in New York and grew up in New Jersey, and his early years could have been easy. His mother, Gladys, was an editor at the New York Times, his father, Pierre, an executive at Columbia Records. By his own account they exposed him to great music, film and literature, and holidayed in France where his interest in food was sparked, but he rebelled, got into trouble at school and began experimenting with drugs while still in his early teens. He got a place at Vassar, an elite formerly all-female college that had only recently begun to accept male students, but dropped out after two years, having experienced kitchen work in local restaurants. He transferred to the prestigious CIA – the Culinary Institute of America – graduating in 1978, before beginning work in New York city’s kitchens

There was more to Bourdain than just being a “bad-boy chef”. As he later said: “I’m not a chef. I’m not bad. And I’m not a boy.” In fact, even by the time Kitchen Confidential was imbuing us all with piratical swagger, he’d already put most of his “bad” behaviour behind him. He was clean, married and working with, what was by all accounts, Stakhanovite zeal on a media career. He was a man who had been through the mill and come out the other side. It was what made his appeal universal. He had indulged his appetites, and learned to live with them without guilt; he could try anything without prejudice and find pleasure in the most refined or most challenging. And this is, at heart, how all food people would like to see themselves.

In recent months, world politics seemed to have given Bourdain’s outlook another context. “I’m proud of the fact that I’ve had as dining companions over the years everybody from Hezbollah supporters, communist functionaries, anti-Putin activists, cowboys, stoners, Christian militia leaders, feminists, Palestinians and Israeli settlers to Ted Nugent. You like food and are reasonably nice at the table? You show me hospitality when I travel? I will sit down with you and break bread.”

Bourdain made no secret of his contempt for Donald Trump and in a recent series shared a bowl of noodles in Vietnam with Barack Obama. At a time when the world is watching the US throw up walls, turn its back on foreigners and generally form the wagons into a circle, he was beginning to look like a one-man rebuttal of the “Ugly American” abroad.

He was not without flaws. Kitchen Confidential was the original handbook for toxic masculinity in the kitchen. Read on one level, it glorifies the kind of behaviour that has been the secret shame of the food industry for decades. On the other hand, like the former addict sharing his story, it comes from that therapeutic necessity to testify, accept responsibility, apologise and move on.

There are big parts of Kitchen Confidential that read, in hindsight, like Bourdain’s personal 12-step programme and many found this, and his friendship with Mario Batali, the US chef facing accusations of sexual misconduct, difficult to come to terms with. That said, Bourdain showed no hesitation in condemning Batali’s behaviour. His involvement with the case of his partner, the actor and director Asia Argento, against the film producer Harvey Weinstein – Argento told the New Yorker magazine last year that she had been sexually assaulted by Weinstein – seemed exemplary. There was no macho railing, no posturing or muscling in, just insistent, respectful solidarity for the #MeToo movement – part of which was an explicit expression of remorse for any effect Kitchen Confidential had.

I met Bourdain once. I’m sure he had no idea who the hell I was, but, like every other schmuck in the food business, I told him he’d inspired me and got me started, and he was good enough to listen. In truth, he meant more to me than that, as he did, it seems, to many. He was constantly getting better. A better writer than a chef, a better communicator than a writer and ultimately, a better man than all of those.

Bourdain was twice divorced. He is survived by Argento; by a daughter, Ariane, from his second marriage, to Ottavia Busia; and by his mother.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion