John Laurens and Hamilton: A Closer Look, Part 1

Processing Request

Processing Request

Welcome to the Charleston Time Machine. I’m Nic Butler, historian at the Charleston County Public Library, and today we’re going begin our conversation in the present with a brief look at the hit Broadway musical, Hamilton, and the best-selling biography that inspired it. That’s just the prelude to our main event, however. Having set the stage, we’ll travel back in Lowcountry history to explore the life and legacy of John Laurens, a Charleston native who is a significant character in both the musical and in the biography of Alexander Hamilton.

More than just a supporting actor, John Laurens was a real, three-dimensional person with his own complicated life story, and there is a very good, well-researched biography of him, written by Gregory Massey and published in 2000 by the University of South Carolina Press. But the portrayal of John Laurens in Ron Chernow’s recent biography of Alexander Hamilton, and in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s recent musical, Hamilton, is pretty shallow, and not entirely factual. More importantly and perhaps controversially, both Chernow’s biography and Miranda’s musical have created a new, popular legacy for Laurens by portraying him as a passionate abolitionist who sought to use the crucible of the American Revolution as a means of breaking down the institution of slavery in the United States. This portrayal is, however, a gross oversimplification of the facts, and so I’d like to offer a bit of humble rebuttal to this misleading bit of contemporary pop culture. Considering how popular the Hamilton phenomenon is at the moment, I think it’s worthwhile to give the story of John Laurens a few extra minutes of our time, so this will be the first of three episodes devoted to the dynamic duo of John Laurens and Alexander Hamilton.

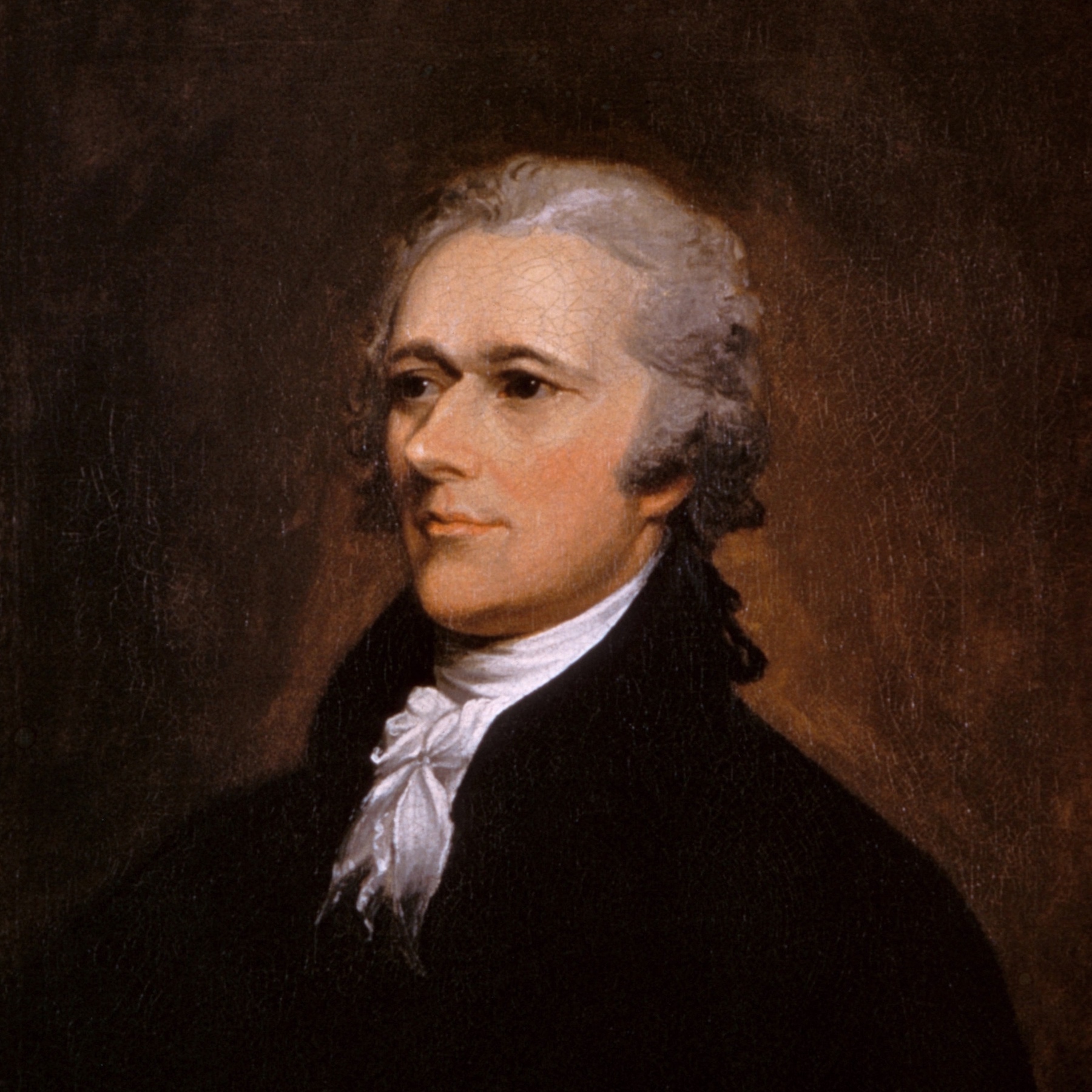

Let’s begin this journey by backing up to the early years of the twenty-first century. In 2004 author Ron Chernow published an 800-page biography, titled simply Alexander Hamilton. This award-wining, best-selling book offers a vivid portrayal of the man, from his obscure beginnings in the 1750s on the Caribbean island of Nevis to his brave service on General Washington’s staff during the American Revolution, through his turbulent but productive years helping to shape the frame of our federal government, to his infamous and fatal duel with Aaron Burr in 1804. Throughout the book, Mr. Chernow’s focus is squarely on Hamilton the man, and the level of personal detail is quite engaging. Meanwhile, the details of other characters and their historical contexts are rendered in much broader, superficial, and occasionally inaccurate, literary strokes. I’m not trying to pan the book, because I found it an enjoyable read. Rather, I’d simply like readers to acknowledge that the book exhibits a clear pro-Hamilton bias, and, on a personal note, I found the author’s understanding of the American Revolution to be frustratingly superficial. I’ll explain more about this topic in a few minutes.

The commercial success of Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography of Alexander Hamilton caught the attention of Lin-Manuel Miranda, who set out to create a theatrical adaptation of Hamilton’s life. Blending a historical storyline with hip-hop musical stylings, Miranda’s 2015 two-act musical, Hamilton, has captivated audiences across the country, and has generally succeeded in making the Revolution and the Constitution seem cool to millions of young Americans. At first glance, Hamilton seems pretty subversive and revolutionary itself. In Act One, Alexander Hamilton and his Revolutionary War comrades, the Marquis de Lafayette, John Laurens, and others, are ultra-cool young bucks itching for glory in an idealistic battle against injustice and oppression. They sing, rap, dance, strut, and swagger to the beat of twenty-first-century grooves, boldly portraying the characters’ youthful enthusiasm in a way that young audiences can relate to. This is not your grandfather’s version of American history.

The commercial success of Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography of Alexander Hamilton caught the attention of Lin-Manuel Miranda, who set out to create a theatrical adaptation of Hamilton’s life. Blending a historical storyline with hip-hop musical stylings, Miranda’s 2015 two-act musical, Hamilton, has captivated audiences across the country, and has generally succeeded in making the Revolution and the Constitution seem cool to millions of young Americans. At first glance, Hamilton seems pretty subversive and revolutionary itself. In Act One, Alexander Hamilton and his Revolutionary War comrades, the Marquis de Lafayette, John Laurens, and others, are ultra-cool young bucks itching for glory in an idealistic battle against injustice and oppression. They sing, rap, dance, strut, and swagger to the beat of twenty-first-century grooves, boldly portraying the characters’ youthful enthusiasm in a way that young audiences can relate to. This is not your grandfather’s version of American history.

At the same time, however, the story line of Hamilton is pretty un-subversive. The facts presented represent conventional, textbook history. In fact, the narrative is so conventional and superficial that it’s not entirely accurate. After all, it’s a pop musical, not a dissertation, and Lin-Manuel Miranda has personally said that Hamilton was never intended as a vehicle for teaching American history. There is absolutely no room in the tight structure of Hamilton for the sort of factual details and subtleties that are also lamentably absent from Ron Chernow’s biography, and absent from most published histories of the Revolutionary era. Personally, I think that’s a shame, because it doesn’t take that much effort to explore a bit more to find and then to include historical details that would make the story both more accurate and more interesting. But what do I know—I’m just a historian, not a Broadway producer. And this isn’t a review of the musical, it’s a show about Charleston history, so let’s move on to the main story.

Over the past several months I’ve spoken with a number of people around Charleston, fans of Hamilton, who asked me what I thought of the portrayal of John Laurens in the musical—was it accurate, was it fair, and wasn’t it just so cool? I have to admit, at first, I had no idea what they were talking about. I am not a consumer of pop culture, and, full disclosure, I am not a fan of the Broadway musical experience. Nevertheless, the question itself is valid—how accurate and fair is portrayal of John Laurens in the musical, Hamilton? And let’s be honest, many young fans of the musical are asking the more basic question: who was John Laurens?

Here’s my short answer to both of these questions: John Laurens was a wealthy young man from Charleston who used his talents, influence, and raw physical energy to fight for independence from Great Britain during the American Revolution. In the end, he fell victim to the military violence of the war, but the portrayal of John Laurens in the musical, Hamilton, is grossly oversimplified, and not entirely accurate. To explain what I mean by this, we’ll have to travel back to the second half of the eighteenth century and take a brief tour of the life and times of John Laurens.

John Laurens was born in Charleston in October 1754 to twenty-three-year-old Eleanor Ball Laurens. His father was thirty-year old Henry Laurens, a young merchant who was quickly rising through the ranks of Charleston society. The son of a saddler, Henry Laurens made a lot of money in the 1750s as a commission merchant in the import-export business. At the same time, he began accumulating tracts of land and became a significant rice planter, profiting from the labor of nearly three hundred enslaved African men, women, and children. Ever the shrewd businessman, Henry Laurens also invested capital in ships sailing to Africa to acquire more slaves to feed South Carolina’s expanding empire of rice. In short, during the childhood of John Laurens, the rapidly increasing wealth and the status his family enjoyed was the product of enslaved African laborers, who enjoyed none of the benefits. Charleston didn’t have a modern school system in the 1750s and 1760s, but the Laurens family had sufficient money to hire private tutors to educate young John at home. In 1770, when John was sixteen, his mother, Eleanor, died. The following year, in the autumn of 1771, Henry Laurens packed up his children and went to London to visit business associates and to place seventeen-year-old John in a proper school. A year later, in the autumn of 1772, John transferred to a French-language school in Geneva, Switzerland, where he stayed for nearly two years. As John approached his twentieth birthday in 1774, his father pressed him to choose a profession and to complete his studies. Somewhat half-heartedly, John Laurens chose to pursue a career in law, and returned to London to acquire the best legal education money could buy.

Sometime after settling in London, John began a relationship with a young lady named Martha Manning, who was the daughter of William Manning, one of Henry Laurens’s business associates. In the early summer of 1776, while the British Navy was bearing down on Sullivan’s Island in South Carolina, Martha Manning became pregnant. John Laurens and Martha were married in October 1776, but John immediately began making plans to travel back to South Carolina, without his new bride. The British colonies on the American mainland were in a state of rebellion, and John desperately wanted to be part of the action. Finally receiving permission from his father to come home, John travelled from London to France in late December 1776, and a month later he sailed from France to the French West Indies and then on to Charleston. John Laurens never saw his young bride again, and he never met his daughter, Frances, who was born in late January 1777.

Shortly after returning to Charleston, in mid-summer 1777, John travelled to Philadelphia with his father, Henry Laurens, who had been elected to represent South Carolina in the Continental Congress. Later that summer, John Laurens joined the American Continental Army, though his rank and assignment at that moment is a bit unclear. From that moment in the late summer of 1777 until his death five years later, John Laurens was constantly in military uniform and in constant search of military glory. A few weeks after joining the army, John participated in his first battle, at Brandywine, Pennsylvania, on September 11th, 1777. After the battle, the Marquis de Lafayette famously said of the young Laurens, “It was not his fault that he was not killed or wounded . . . he did every thing that was necessary to procure one or the other.”

In early October 1777, twenty-three-year-old John Laurens fought in the battle of Germantown, Pennsylvania, where he again showed reckless courage. Shortly thereafter, General George Washington invited the young Laurens to join his staff as an aide-de-camp with the rank of major. Here he joined other young men on Washington’s staff, including twenty-something Alexander Hamilton, and twenty-year-old Gilbert du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette.

In early October 1777, twenty-three-year-old John Laurens fought in the battle of Germantown, Pennsylvania, where he again showed reckless courage. Shortly thereafter, General George Washington invited the young Laurens to join his staff as an aide-de-camp with the rank of major. Here he joined other young men on Washington’s staff, including twenty-something Alexander Hamilton, and twenty-year-old Gilbert du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette.

During the bitter winter of 1777–78, John Laurens camped with General Washington and his army at Valley Forge, about twenty miles from British-held Philadelphia. Conditions and morale were terrible, and the army lacked sufficient resources to cloth and feed the soldiers. The nascent American government was dogged by perpetual difficulties in filling the ranks of its Continental regiments. The First regiment of Rhode Island regulars, in particular, was having a terrible time recruiting men. After some debate, in January 1778 General Washington tacitly approved a proposal to fill two undermanned Rhode Island battalions with armed slaves, who, in return for faithful service, would later receive their freedom. Because of this action, historians sometime refer to the Rhode Island 1st Regiment as the “black regiment,” but in reality it was only partially black. At any rate, the decision to allow enslaved men into the army as soldiers, not just as laborers, immediately caught the attention of John Laurens. Having grown up in a world of privilege created on the backs of enslaved laborers, John must have realized the potential implications of this racial change, both in terms of the American army in general and in terms of his personal career. In South Carolina, where enslaved people formed a much larger part of the population than in the north, whole companies, even battalions, and perhaps even regiments of armed slaves could be formed. And as an experienced officer, a native of South Carolina, and as the scion of a great slave-holding family, John Laurens realized he might be the ideal candidate to lead such a force against the British army. This scenario might be his opportunity to achieve the fame, glory, and honor he so desperately wanted.

In mid-January 1778, twenty-three-year-old John Laurens wrote to his father Henry about taking some Laurens-family slaves and forming a prototype, of you will, for a black battalion in South Carolina. Since he was destined to inherit a large number of enslaved people, John reasoned, could he not take early possession of his inheritance and arm them for battle? It was not the first time father and son had discussed the subjects of slavery and emancipation. In the heat of the Revolution, filled with the rhetoric of liberty and human rights, both men agreed that the practice of slavery was immoral and should end, eventually and gradually. Henry Laurens was content to delay emancipation until the proper circumstances appeared, sometime vaguely after the war. But in January 1778, John Laurens saw an opportunity to set in motion immediately a path toward the end of slavery. By arming black men and training them to fight for American liberty, he could help slaves make a transition to citizenship. Henry Laurens dismissed the plan, arguing that John would have little success in convincing enslaved black men to risk their lives in return for the vague promise of a latter freedom. John countered by saying he believed enslaved men would recognize the value of the opportunity, and that their brave service would win them general respect after the war. “When can it be better done,” John wrote to his father, “than when their enfranchisement [that is, their freedom,] may be made conducive to the public good?” It was a good argument, to be sure, but Henry was still skeptical. He believed that John’s real motivation was simply to lead men into glory on the battlefield. Why not return home to South Carolina, Henry wrote to his son, and raise a regiment of white men to fulfill your desire for military fame? John was insulted by the implication that his passion was really motivated by personal ambition. As a man of feeling and sentiment, well-versed in the latest moral philosophy and notions of self-understanding, John Laurens resented his father’s base assertions, and, in the spring of 1778, dropped the matter.

So, do the 1778 letters of John Laurens show him to be an abolitionist? Well, perhaps, in the abstract, at least. John said he had long deplored the institution of slavery, and had an “ardent desire to assert the rights of humanity” by providing a realistic pathway to freedom. But consider this fact, noted by John Laurens’s biographer, Gregory Massey. In the bitter winter of 1778 at Camp Valley Forge, John Laurens frequently asked his father to send clothing and accessories for his fellow soldiers. Henry Laurens obliged, and included two shirts for Shrewsbury, the enslaved man who served as John Laurens’s personal valet. John Laurens responded to his father that Shrewsbury was not in need. While it was important to find proper clothing for the white soldiers, John said, Shrewsbury could “do without.”[1]

The 1778 correspondence of John and Henry Laurens is briefly mentioned in Ron Chernow’s biography of Alexander Hamilton, but Chernow is much more emphatic about John’s moral sentiments. He calls Laurens an “unwavering abolitionist,” and states that this trait formed a strong ideological bond between Laurens and Hamilton throughout the war.[2] In my opinion, however, I believe Mr. Chernow overstates the case a bit. It is clear from the surviving letters of John Laurens that he held a passionate belief in the natural rights of all men, that he recognized the humanity and potential of enslaved people, and that he abhorred the violence of the slave trade. But John’s expression of these sentiments did waver, according to his circumstances. And curiously, in the last few years of his life, he professed these beliefs only at times when the issue seemed convenient for the advancement of his career. Had John Laurens survived the war, or had he been permitted to raise his black regiment, we might see more clearly his true feelings on the abolition of slavery.

Early in Act 1 of the musical, Hamilton, the main characters perform a number called “My Shot,” in which each man in turn raps about his aspirations, what he hopes to achieve in the Revolution. The war has provided them with great opportunities, a shot at greatness, if you will, and each man proclaims, “I’m not going to throw away my shot.” When it’s John Laurens’s turn, he steps forward and raps the following lines:

But we’ll never be truly free

Until those in bondage have the same rights as you and me

You and I. Do or die. Wait till I sally in

On a stallion with the first black battalion

In the bleak winter of 1778, however, there already were two battalions composed largely of black soldiers, and John Laurens’s quarrel with his wealthy father forced him to postpone his dream to lead his own black battalion, at least for a few more months.

And that’s where we’ll end our first installment of this look at the real story of John Laurens and Alexander Hamilton. I hope you’ve enjoyed this journey into the past aboard the Charleston Time Machine, and I hope you’ll join me next week for the continuation of this great story.

[1] Gregory D. Massey, John Laurens and the American Revolution (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 93–96.

[2] Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (Penguin Press, 2004), 121, 210.

NEXT: John Laurens and Hamilton, Part 2

PREVIOUSLY: Ten Things Everyone Should Know about Lowcountry Rice

See more from Charleston Time Machine