English Literature: Victorians and Moderns

English Literature: Victorians and Moderns

Dr. James Sexton

English Literature: Victorians and Moderns by James Sexton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

To learn more about BCcampus Open Textbook project, visit http://open.bccampus.ca

© James Sexton 2014. English Literature:Victorians and Moderns is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License, except where otherwise noted. Under this license, any user of this textbook or the textbook contents herein must provide proper attribution as follows:

- If you redistribute this textbook in a digital format (including but not limited to EPUB, PDF, and HTML), then you must retain on every page the following attribution: Download for free at http://open.bccampus.ca/find-open-textbooks/

- If you redistribute this textbook in a print format, then you must include on every physical page the following attribution: Download for free at http://open.bccampus.ca/find-open-textbooks/

- If you redistribute part of this textbook, then you must retain in every digital format page view (including but not limited to EPUB, PDF, and HTML) and on every physical printed page the following attribution: Download for free at http://open.bccampus.ca/find-open-textbooks/

- If you use this textbook as a bibliographic reference, then you should cite it as follows: BCcampus, Name of Textbook or OER. 21 June 2012. <http://open.bccampus.ca/find-open-textbooks/>.

For questions regarding this licensing, please contact opentext@bccampus.ca

Cover image: Old Leather books, 4 by Wyoming_Jackrabbit used under a CC-BY-NC-SA license.

Note: Much of the material in this book has been reproduced and made available based on its public domain status in Canada. If you are not in Canada and using these materials, you acknowledge that it is your responsibility to comply with the applicable copyright laws in your jurisdiction.

Contents

- Acknowledgements

- About the Book

- Preface

- The Victorian Era 1832–1901

- Introduction

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861)

- Biography

- Sonnets from the Portuguese public-domain

- The Cry of the Children public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Robert Browning (1812–1889)

- Biography

- Porphyria's Lover public-domain

- My Last Duchess public-domain

- The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church public-domain

- Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892)

- Biography

- The Lady of Shalott public-domain

- From the Princess public-domain

- The Lotos-Eaters public-domain

- Ulysses public-domain

- Break, Break, Break public-domain

- from In Memoriam A. H. H. public-domain

- The Charge of the Light Brigade public-domain

- Crossing the Bar public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

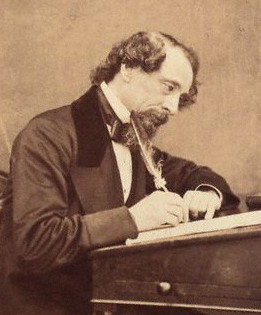

- Charles Dickens (1812–1870)

- Biography

- A Christmas Carol: Stave 1 public-domain

- A Christmas Carol: Stave 2 public-domain

- A Christmas Carol: Stave 3 public-domain

- A Christmas Carol: Stave 4 public-domain

- A Christmas Carol: Stave 5 public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Christina Rossetti (1830–1894)

- Biography

- Goblin Market public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Henry James (1843–1916)

- Biography

- Turn of the Screw: Introduction public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 1 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 2 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 3 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 4 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 5 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 6 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 7 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 8 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 9 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 10 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 11 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 12 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 13 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 14 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 15 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 16 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 17 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 18 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 19 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 20 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 21 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 22 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 23 public-domain

- Turn of the Screw: Chapter 24 public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

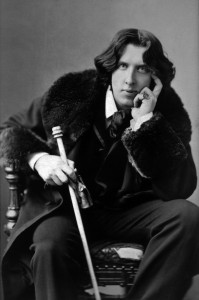

- Oscar Wilde (1854–1900)

- Biography

- The Importance of Being Earnest: Act I public-domain

- The Importance of Being Earnest: Act II public-domain

- The Importance of Being Earnest: Act III public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

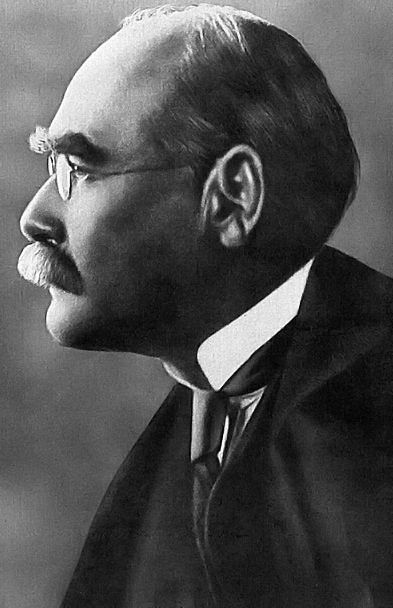

- Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936)

- Biography

- Fuzzy-Wuzzy public-domain

- Recessional public-domain

- The White Man’s Burden public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

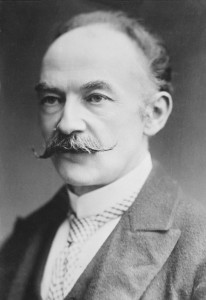

- Thomas Hardy (1840–1928)

- Biography

- Hap public-domain

- Drummer Hodge public-domain

- The Subalterns public-domain

- The Ruined Maid public-domain

- The Impercipient public-domain

- Mad Judy public-domain

- The Going public-domain

- The Haunter public-domain

- The Convergence of the Twain public-domain

- Ah, Are You Digging on My Grave? public-domain

- Let Me Enjoy public-domain

- Channel Firing public-domain

- The Man He Killed public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

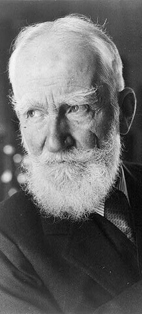

- George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950)

- Biography

- Major Barbara: Act I public-domain

- Major Barbara: Act II public-domain

- Major Barbara: Act III public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Joseph Conrad (1857–1924)

- Biography

- Heart of Darkness: Chapter 1 public-domain

- Heart of Darkness: Chapter 2 public-domain

- Heart of Darkness: Chapter 3 public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- William Butler Yeats (1865–1939)

- Biography

- The Lake Isle of Innisfree public-domain

- No Second Troy public-domain

- Easter, 1916 public-domain

- The Wild Swans at Coole public-domain

- The Second Coming public-domain

- A Prayer for My Daughter public-domain

- Leda and the Swan public-domain

- Sailing to Byzantium public-domain

- Among School Children public-domain

- Byzantium public-domain

- Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop public-domain

- The Circus Animals' Desertion public-domain

- Study Questions and Activities

- A.E. Housman (1859–1936)

- Biography

- Loveliest of Trees public-domain

- Farewell to Barn and Stack and Tree public-domain

- To an Athlete Dying Young public-domain

- Is My Team Ploughing? public-domain

- [Additional Poems] public-domain

- [More Poems] public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Hector Hugh Munro (Saki) (1870–1916)

- Biography

- The Open Window public-domain

- The Schartz-Metterklume Method public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- World War I Poetry

- Introduction

- Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

- Biography

- Disabled public-domain

- Dulce et Decorum Est public-domain

- Futility public-domain

- S.I.W. public-domain

- Mental Cases public-domain

- Smile, Smile, Smile public-domain

- Anthem for Doomed Youth public-domain

- The Sentry public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967)

- Biography

- Counter-Attack

- Does it Matter?

- The Death Bed

- Base Details and Glory of Women

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918)

- Biography

- Returning, We Hear the Larks public-domain

- Break of Day in the Trenches

- Dead Man's Dump public-domain

- Study Questions and Activities

- Rupert Brooke (1887–1915)

- Biography

- Oxford JISC Tutorial: Rupert Brooke

- Study Questions and Activities

- Sean O’Casey (1880–1964)

- Biography

- Explanatory Notes to Juno and the Paycock

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Virginia Woolf (1882–1941)

- Biography

- To the Lighthouse: Introduction

- To the Lighthouse public-domain

- Professions for Women public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- James Joyce (1882-1941)

- Biography

- Dubliners: Araby public-domain

- Dubliners: Eveline public-domain

- Dubliners: After the Race public-domain

- Dubliners: Counterparts public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930)

- Biography

- The Horse Dealer's Daughter public-domain

- The Rocking Horse Winner public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- T.S. Eliot (1888–1965)

- Biography

- The Hollow Men

- The Journey of the Magi

- Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

- The Waste Land

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Katherine Mansfield (1888–1923)

- Biography

- Miss Brill public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: I public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: II public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: III public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: IV public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: V public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: VI public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: VII public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: VIII public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: IX public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: X public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: XI public-domain

- The Daughters of the Late Colonel: XII public-domain

- The Fly public-domain

- A Cup of Tea public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Aldous Huxley (1894–1963)

- Biography

- Brave New World: Chapter 1 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 2 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 3 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 4 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 5 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 6 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 7 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 8 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 9 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 10 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 11 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 12 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 13 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 14 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 15 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 16 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 17 public-domain

- Brave New World: Chapter 18 public-domain

- Study Questions and Activities

- George Orwell (1903-1950)

- Biography

- Pleasure Spots public-domain

- Can Socialists be Happy? public-domain

- Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

- Appendix 1: A Mini-Casebook on The Turn of the Screw

- Appendix 2: A Mini-Casebook on Brave New World

- Appendix 3: A Mini-Casebook on Heart of Darkness

- Appendix 4: Glossary of Literary Terms

- Appendix 5: Writing an Analysis of a Poem, Story, or Play

- Appendix 6: Documenting Essays in MLA Style

- Versioning History

1

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank his project manager, Amanda Coolidge; his co-editors Dr. Alix Hawley (Virigina Woolf); Ms. Kate Soles (Appendix: Glossary of Literary Terms); Dr. Derek Soles (Conrad, Yeats, Eliot, Appendix: Writing an Analysis of a Poem, Story or Play); and Drs. Brad Congdon, David Leon Higdon, Mary E. Kapke, Carol Lowe, Jerome Meckier, Colin Norman, Willi Real, as well as the editors of Aldous Huxley Annual (LIT Verlag), and English Studies in Canada for permission to reprint previously published essays in this open textbook.

2

About the Book

English Literature was written by James Sexton. The creation is a part of the B.C. Open Textbook project.

The B.C. Open Textbook Project began in 2012 with the goal of making post-secondary education in British Columbia more accessible by reducing student cost through the use of openly licensed textbooks. The BC Open Textbook Project is administered by BCcampus and funded by the British Columbia Ministry of Advanced Education.

Open textbooks are open educational resources (OER); they are instructional resources created and shared in ways so that more people have access to them. This is a different model than traditionally copyrighted materials. OER are defined as teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits their free use and re-purposing by others (Hewlett Foundation). Our open textbooks are openly licensed using a Creative Commons license, and are offered in various e-book formats free of charge, or as printed books that are available at cost. For more information about this project, please contact opentext@bccampus.ca. If you are an instructor who is using this book for a course, please let us know.

3

Preface

This open textbook was originally planned as a stand-alone anthology for various one-semester second-year Modern English Literature courses in the British Columbia colleges and universities system, but it can also be used elsewhere and at other levels, or as a supplementary text for the Victorians and Moderns portions of British literature survey courses. Besides its portability, searchability, and compatibility with smart phones, tablets, e-readers, and laptop or desktop computers, students should welcome its free availability online anywhere in the world, providing instant access to a variety of enriching photographic, audio, and video resources via the Internet. Another key feature is the series of six appendices, containing three mini-casebooks, a glossary of literary terms, and practical guides to writing literary essays and documenting them in correct MLA format. These “controlled” research casebooks and guides should be particularly helpful to students without easy access to the resources of large academic libraries. Its defects are wholly the responsibility of the editor. In the explanatory apparatus, he has tried to avoid the faults attributed by Aldous Huxley to certain editors, whom he chides for fulsomely explaining and discussing “the obvious points” while passing over “the hard passages, about which one might want to know something,…in the silence of sheer ignorance” (Limbo 197).

Such a project would not have been possible without those whose labours have resulted in the invaluable Internet digital libraries and resources such as Archive.org, Professor George Landow’s The Victorian Web, Oxford University’s First World War Poetry Digital Archive, the Poets.org site of the American Academy of Poets, various BBC and British Library educational sites, Wikimedia Commons and its sister sites, as well as numerous other helpful public Internet sites maintained by universities and individuals.

James Sexton

Vancouver, September 12, 2014

I

The Victorian Era 1832–1901

1

Introduction

Although Queen Victoria did not ascend to the throne until 1837, it is common to refer to the Victorian era as beginning in 1832, the year of both the First Reform Bill and the death of Sir Walter Scott, a major writer of the Romantic era. The main topics for this unit on the Victorians are Industrialism, Religious Doubt, The Role of Women (“The Woman Question”) and Imperialism. This is not to say that these issues were peculiar to that era; indeed, we will see them reappearing in later units; for example, the “Woman Question” in the Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield chapters, Industrialism in Shaw’s play Major Barbara and in Huxley’s Brave New World, and Imperialism and Religious Doubt in the Orwell and Eliot chapters respectively.

As one critic puts it, the following developments characterize the Victorian era:

- A decisive shift of population and political and economic power from the country estates to the cities and the consequent increasing dominance of the middle classes

- Industrialization and the “proletarianization” of the working class

- The laissez-faire school of economics, along with the countervailing current of social reform movements and the emergence of Marxian socialism

- The dramatic expansion of English naval and trade dominance and the extension of the British Empire around the globe

- The exposition of the theory of evolution by Darwin and his defenders and the heightened conflict between science and religion (Adapted from George Scheper A Survey of English Literature. Maryland Center for Public Broadcasting 1973).

Resources

Industrialism

- https://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/victorian/topic_1/welcome.htm

- http://www.victorianweb.org/technology/index.html

- “1832 Reform Act.” Taking Liberties: The Struggle for Britain’s Freedoms and Rights. The British Library. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/takingliberties/staritems/111832reformact.html

- “The 1833 Factory Act.” The Victorian Web. Dr. Marjie Bloy, National University of Singapore. http://www.victorianweb.org/history/factact.html

- “Child Labor.” The Victorian Web. David Cody, Hartwick College. http://www.victorianweb.org/history/hist8.html

- “The Crystal Palace, or The Great Exhibition of 1851: An Overview.” The Victorian Web. http://www.victorianweb.org/victorian/history/1851/index.html

- “Great Exhibition.” Treasures. The National Archives. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/victorians/exhibition/greatexhibition.html

- “The Life of the Industrial Worker in Nineteenth-Century England.” The Victorian Web. Laura Del Col, West Virginia University. http://www.victorianweb.org/history/workers2.html

- “Social Darwinism.” http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Social_Darwinism

- “The Reform Acts.” The Victorian Web. Glenn Everett, University of Tennessee at Martin. http://www.victorianweb.org/history/hist2.html

- “Uberindustrialism” http://ubervictorianindustrialism.tumblr.com/

Religious Doubt

- “Victorian Science & Religion.” The Victorian Web. Aileen Fyfe, National University of Ireland Galway and John van Wyhe, Cambridge University. http://www.victorianweb.org/science/science&religion.html

- “Victorian Geology.” The Victorian Web. John van Wyhe, Cambridge University. http://www.victorianweb.org/science/geology.htm

- “Dover Beach”, Matthew Arnold. The Victorian Web. [With commentary]. http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/arnold/writings/doverbeach.html

Women’s Rights

- “The Woman Question”: Overview Norton Online https://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/victorian/topic_2/welcome.htm

- “The Nature of Women”. https://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/victorian/topic_2/nature.htm

- “The 1870 Education Act.” Living Heritage: Going to School. www.parliament.uk. http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/school/overview/1870educationact/

- “Gender Ideology & Separate Spheres.” Gender, Health, Medicine & Sexuality in Victorian England. Victoria & Albert Museum. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/g/gender-ideology-and-separate-spheres-19th-century/

- “Gender Matters.” The Victorian Web. http://www.victorianweb.org/gender/

- “The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies.” The Victorian Web. Helena Wojtczak. http://www.victorianweb.org/gender/wojtczak/nuwss.html

- “‘The Personal is Political’: Gender in Private & Public Life.” Gender, Health, Medicine & Sexuality in Victorian England. Victoria & Albert Museum. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/p/the-personal-is-political-gender-in-private-and-public-life/

- “Suffragists.” Learning: Dreamers and Dissenters. The British Library. http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/struggle/struggle.html

- “Victorian Britain: A Divided Nation?” Education. The National Archives. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/victorianbritain/divided/

Imperialism

- “The British Empire.” The Victorian Web. David Cody, Hartwick College. http://www.victorianweb.org/history/empire/Empire.html

- “British Empire.” The National Archives. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/empire/

- “Kipling’s Imperialism.” The Victorian Web. David Cody, Hartwick College. http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/kipling/rkimperialism.html

- Norton Topics: “Victorian Imperialism”.

- https://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/victorian/topic_4/welcome.htm

- “The British Empire” http://www.victorianweb.org/history/empire/index.html

- “Archaeology and Imperialism.” BBC Radio In Our Time. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p003k9gt

A Comprehensive general Victorians Site from Saylor.org English 410 Resources Page.

http://www.saylor.org/courses/engl410/?ismissing=0&resourcetype=1

II

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861)

2

Biography

Born in 1806 at Coxhoe Hall, Durham, England, Elizabeth Barrett was an English poet influenced by the Romantic movement. The oldest of 12 children, Elizabeth was the first in her family born in England in over 200 years. For centuries, the Barrett family, who were part Creole, had lived in Jamaica, where they owned sugar plantations and relied on slave labor. Elizabeth’s father, Edward Barrett Moulton Barrett, chose to raise his family in England while his fortune grew in Jamaica.

Educated at home, Elizabeth apparently had read passages from Paradise Lost and a number of Shakespearean plays, among other great works, before the age of 10. By her 12th year she had written her first “epic” poem, which consisted of four books of rhyming couplets. Two years later, Elizabeth developed a lung ailment that plagued her for the rest of her life. Doctors began treating her with morphine, which she would take until her death. While saddling a pony when she was 15, Elizabeth also suffered a spinal injury. Despite her ailments, her education continued to flourish. Throughout her teenage years, Elizabeth taught herself Hebrew so that she could read the Old Testament; her interests later turned to Greek studies. Accompanying her appetite for the classics was a passionate enthusiasm for her Christian faith, and she became active in the Bible and missionary societies of her church.

In 1826 Elizabeth anonymously published her collection An Essay on Mind and Other Poems. Two years later, her mother passed away. The slow abolition of slavery in England and mismanagement of the plantations depleted the Barrett’s income, and in 1832, Elizabeth’s father sold his rural estate at a public auction. He moved his family to a coastal town and rented cottages for the next three years before settling permanently in London. While living on the sea coast, Elizabeth published her translation of Prometheus Bound (1833), by the Greek dramatist Aeschylus.

Gaining attention for her work in the 1830s, Elizabeth continued to live in her father’s London house under his tyrannical rule. He began sending Elizabeth’s younger siblings to Jamaica to help with the family’s estates. Elizabeth bitterly opposed slavery and did not want her siblings sent away. During this time, she wrote The Seraphim and Other Poems (1838), expressing Christian sentiments in the form of classical Greek tragedy. Due to her weakening disposition, she was forced to spend a year at the sea in Torquay accompanied by her brother Edward, whom she referred to as “Bro.” He drowned later that year while sailing, and Elizabeth returned home emotionally broken, becoming an invalid and a recluse. She spent the next five years in her bedroom at her father’s home. She continued writing, however, and in 1844 produced a collection entitled simply Poems. This volume gained the attention of poet Robert Browning, whose work Elizabeth had praised in one of her poems, and he wrote her a letter.

Elizabeth and Robert, who was six years her junior, exchanged 574 letters over the next 20 months. Immortalized in 1930 in the play The Barretts of Wimpole Street, by Rudolf Besier (1878–1942), their romance was bitterly opposed by her father, who did not want any of his children to marry. In 1846, the couple eloped and settled in Florence, Italy, where Elizabeth’s health improved and she bore a son, Robert Wideman Browning. Her father never spoke to her again. Elizabeth’s Sonnets from the Portuguese, dedicated to her husband and written in secret before her marriage, was published in 1850. Critics generally consider the Sonnets—one of the most widely known collections of love lyrics in English—to be her best work. Admirers have compared her imagery to Shakespeare and her use of the Italian form to Petrarch.

Political and social themes embody Elizabeth’s later work. She expressed her intense sympathy for the struggle for the unification of Italy in Casa Guidi Windows (1848–1851) and Poems Before Congress (1860). In 1857, Browning published her verse novel Aurora Leigh, which portrays male domination of a woman. In her poetry, she also addressed the oppression of the Italians by the Austrians, the child labor mines and mills of England, and slavery, among other social injustices. Although this decreased her popularity, Elizabeth was read and recognized around Europe.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in Florence on June 29, 1861.

Reprinted with the permission of the Academy of American Poets, 75 Maiden Lane, Suite 901, New York, NY. www.poets.org.

3

Sonnets from the Portuguese

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

XXI

Say over again, and yet once over again,

That thou dost love me. Though the word repeated

Should seem a “cuckoo-song,Repetitious.” as thou dost treat it,

Remember, never to the hill or plain,

Valley and wood, without her cuckoo-strain

Comes the fresh Spring in all her green completed.

Beloved, I, amid the darkness greeted

By a doubtful spirit-voice, in that doubt’s pain

Cry, “Speak once more—thou lovest!” Who can fear

Too many stars, though each in heaven shall roll,

Too many flowers, though each shall crown the year?

Say thou dost love me, love me, love me—toll

The silver iterance!—only minding, Dear,

To love me also in silence with thy soul.

XXII

When our two souls stand up erect and strong,

Face to face, silent, drawing nigh and nigher,

Until the lengthening wings break into fire

At either curved point,—what bitter wrong

Can the earth do to us, that we should not long

Be here contented? Think! In mounting higher,

The angels would press on us and aspire

To drop some golden orb of perfect song

Into our deep, dear silence. Let us stay

Rather on earth, Beloved,—where the unfit

Contrarious moods of men recoil away

And isolate pure spirits, and permit

A place to stand and love in for a day,

With darkness and the death-hour rounding it.

XXXII

The first time that the sun rose on thine oath

To love me, I looked forward to the moon

To slacken all those bonds which seemed too soon

And quickly tied to make a lasting troth.

Quick-loving hearts, I thought, may quickly loathe;

And, looking on myself, I seemed not one

For such man’s love!—more like an out-of-tune

Worn viol, a good singer would be wroth

To spoil his song with, and which, snatched in haste,

Is laid down at the first ill-sounding note.

I did not wrong myself so, but I placed

A wrong on thee. For perfect strains may float

‘Neath master-hands, from instruments defaced,—

And great souls, at one stroke, may do and doat.

XLIII

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of Being and ideal Grace.

I love thee to the level of everyday’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candlelight.

I love thee freely, as men strive for Right;

I love thee purely, as they turn from Praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints,—I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life!—and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

—1845-47, 1850

4

The Cry of the Children

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

“Φηῦ, φηῦ, τί προσδέρκεσθέ μ’ ὄμμασιν, τέκνα;”—MedeaThe title and first line are taken from the Chorus in response to the murders being committed in Euripedes’ tragedy, Medea. Browning wrote the poem in response to The Report of the Children’s Employment Commission (1843) by her friend, the poet Richard Henry Horne, who exposed the abuses against children employed in British mines and factories..

[Alas, alas, why do you gaze at me with your eyes, my children?]

Do ye hear the children weeping, O my brothers,

Ere the sorrow comes with years?

They are leaning their young heads against their mothers,

And that cannot stop their tears.

The young lambs are bleating in the meadows;

The young birds are chirping in the nest,

The young fawns are playing with the shadow,

The young flowers are blowing toward the west—

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

They are weeping bitterly!

They are weeping in the playtime of the others,

In the country of the free.

Do you question the young children in the sorrow

Why their tears are falling so?

The old man may weep for his to-morrow

Which is lost in Long Ago;

The old tree is leafless in the forest,

The old year is ending in the frost,

The old wound, if stricken, is the sorest,

The old hope is hardest to be lost:

But the young, young children, O my brothers,

Do you ask them why they stand

Weeping sore before the bosoms of their mothers,

In our happy Fatherland?

They look up with their pale and sunken faces,

And their looks are sad to see,

For the man’s hoary anguish draws and presses

Down the cheeks of infancy;

“Your old earth,” they say, “is very dreary,

Our young feet,” they say, “are very weak;

Few paces have we taken, yet are weary—

Our grave-rest is very far to seek:

Ask the aged why they weep, and not the children,

For the outside earth is cold,

And we young ones stand without, in our bewildering,

And the graves are for the old!”

“True,” say the children, “it may happen

That we die before our time:

Little Alice died last year, her grave is shapen

Like a snowball, in the rime.Frost.

We looked into the pit prepared to take her:

Was no room for any work in the close clay!

From the sleep wherein she lieth none will wake her,

Crying, ‘Get up, little Alice! it is day.’

If you listen by that grave, in sun and shower,

With your ear down, little Alice never cries;

Could we see her face, be sure we should not know her,

For the smile has time for growing in her eyes,—

And merry go her moments, lulled and stilled in

The shroud, by the kirk-chime!Church bell.

“It is good when it happens,” say the children,

“That we die before our time.”

Alas, alas, the children! they are seeking

Death in life, as best to have!

They are binding up their hearts away from breaking,

With a cerementShroud. from the grave.

Go out, children, from the mine and from the city,

Sing out, children, as the little thrushes do;

Pluck you handfuls of the meadow-cowslips pretty,

Laugh aloud, to feel your fingers let them through!

But they answer, “Are your cowslips of the meadows

Like our weeds anear the mine?

Leave us quiet in the dark of the coal-shadows,

From your pleasures fair and fine!

“For oh,” say the children, “we are weary,

And we cannot run or leap;

If we cared for any meadows, it were merely

To drop down in them and sleep.

Our knees tremble sorely in the stooping,

We fall upon our faces, trying to go;

And, underneath our heavy eyelids drooping,

The reddest flower would look as pale as snow.

For, all day, we drag our burden tiring,

Through the coal-dark, underground;

Or, all day, we drive the wheels of iron

In the factories, round and round.”

“For all day, the wheels are droning, turning;

Their wind comes in our faces,

Till our hearts turn, our heads with pulses burning,

And the walls turn in their places:

Turns the sky in the high window blank and reeling,

Turns the long light that drops adown the wall,

Turn the black flies that crawl along the ceiling;

All are turning, all the day, and we with all.

And all day, the iron wheels are droning,

And sometimes we could pray,

‘O ye wheels,’ (breaking out in a mad moaning),

‘Stop! be silent for to-day !’ ”

Ay! be silent ! Let them hear each other breathing

For a moment, mouth to mouth!

Let them touch each other’s hands, in a fresh wreathing

Of their tender human youth!

Let them feel that this cold metallic motion

Is not all the life God fashions or reveals:

Let them prove their living souls against the notion

That they live in you, or under you, O wheels!

Still, all day, the iron wheels go onward,

Grinding life down from its mark;

And the children’s souls, which God is calling sunward,

Spin on blindly in the dark.

Now tell the poor young children, O my brothers,

To look up to Him and pray;

So the blessed One who blesseth all the others,

Will bless them another day.

They answer, “Who is God that He should hear us,

While the rushing of the iron wheels is stirred?

When we sob aloud, the human creatures near us

Pass by, hearing not, or answer not a word!

And we hear not (for the wheels in their resounding)

Strangers speaking at the door:

Is it likely God, with angels singing round Him,

Hears our weeping any more?

“Two words, indeed, of praying we remember,

And at midnight’s hour of harm,

‘Our Father,’ looking upward in the chamber,

We say softly for a charm.

We know no other words, except ‘Our Father,’

And we think that, in some pause of angels’ song,

God may pluck them with the silence sweet to gather,

And hold both within His right hand which is strong.

‘Our Father!’ If He heard us, He would surely

(For they call Him good and mild)

Answer, smiling down the steep world very purely,

‘Come and rest with me, my child.’

“But, no!” say the children, weeping faster,

“He is speechless as a stone:

And they tell us, of His image is the master

Who commands us to work on.

Go to!” say the children,— “up in Heaven,

Dark, wheel-like, turning clouds are all we find.

Do not mock us; grief has made us unbelieving:

We look up for God, but tears have made us blind.”

Do ye hear the children weeping and disproving,

O my brothers, what ye preach?

For God’s possible is taught by His world’s loving —

And the children doubt of each.

And well may the children weep before you!

They are weary ere they run;

They have never seen the sunshine, nor the glory

Which is brighter than the sun:

They know the grief of man, without its wisdom;

They sink in man’s despair, without its calm;

Are slaves, without the liberty in Christdom,

Are martyrs, by the pang without the palm:

Are worn, as if with age, yet unretrievingly

The harvest of its memories cannot reap,—

Are orphans of the earthly love and heavenly:

Let them weep! let them weep!

They look up, with their pale and sunken faces,

And their look is dread to see,

For they mind you of their angels in high places,

With eyes turned on Deity.

“How long,” they say, “how long, O cruel nation,

Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart, —

Stifle down with a mailed heel its palpitation,

And tread onward to your throne amid the mart?

Our blood splashes upward, O gold-heaper,

And your purplecf. Donne, invoking Herod’s slaughter of the children in Matthew 2: 16: “...hast thou since/Purpled thy nail in blood of innocence?”, “The Flea.” shows your path!

But the child’s sob in the silence curses deeper

Than the strong man in his wrath!”

—1843

5

Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

Study Questions and Activities

Sonnets from the Portuguese

1. Determine the rhyme scheme for each of these sonnets. To what type do the Sonnets from the Portuguese belong—the English or the Petrarchan form?

2. Log on to the Wikisource page for all 43 sonnets. Do any of the sonnets break from the standard rhyme scheme used in sonnets 21, 22, 32, and 43 above?

3. In terms of form, especially rhyme scheme, which English sonneteer does Barrett Browning most resemble: Sidney, Spenser, or Shakespeare? For Sidney, see Astrophil and Stella, Sonnets 31, 52, 74, http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~rbear/stella.html. For Spenser, see any of the sonnets in Amoretti, http://darkwing.uoregon.edu/~rbear/amoretti.html#1. For Shakespeare, see http://www.opensourceshakespeare.org/views/sonnets/sonnet_view.php?Sonnet=1

4. Barrett Browning knew the poetry of John Donne very well. Do any of the above sonnets resemble Donne’s “sonnets” in terms of style or imagery?

5. In a short essay, compare and contrast one sonnet by Browning and one by either Shakespeare, Sidney, or Spenser.

Cry of the Children

Professor Florence Boos maintains an extensive site on Victorian literature, with helpful questions on many Victorian authors. The index to her study guides is well worth downloading. It can be found at the bottom of her page devoted to E.B. Browning’s “Cry of the Children” and “The Runaway Slave” below:

http://www.uiowa.edu/~boosf/questions/ebbrunawayweb.htm

1. In particular, are there ways in which the rhythms reinforce the theme of noisy, dirty, and unpleasant factory conditions?

2. What metaphors or recurrent themes does the author use to make her points (nature; death; youth and age; whirring of machinery)?

3. In what ways is the children’s viewpoint different from that of adults? What is their view of death, and how does this reinforce the poem’s themes? How do they respond to the death of little Alice?

4. What view of religion does the author seem to espouse? Who is responsible for the fact that the children are unable to conceive of a beneficent divine being?

Activities/Further Essay Topics

1. Compare the document from the Victorian Web about child labour with “Cry of the Children”; then discuss which is the more likely to make the reader take action against the abuses:

- “Testimony Gathered by Ashley’s Mines Commission.” The Victorian Web. Laura Del Col, West Virginia University. http://www.victorianweb.org/history/ashley.html

2. Compare Barrett Browning’s description of child labour with Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, particularly in the poems “Holy Thursday” and “Chimney Sweeper.” Compare the children’s attitude toward religion in both authors’ works. Compare the last line of “The Chimney Sweeper” with the last stanza of “The Cry of the Children.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Chimney_Sweeper

References

Figure 1:

Elizabeth Barrett Browning by Project Gutenberg (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elizabeth_Barrett_Browning_2.jpg) is in the Public Domain

III

Robert Browning (1812–1889)

6

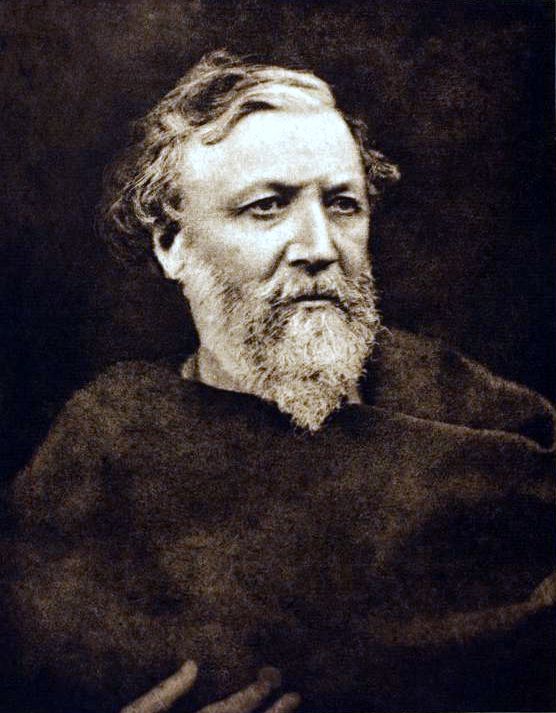

Biography

Robert Browning was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father worked as a bank clerk and was also an artist, scholar, antiquarian, and collector of books and pictures. His rare book collection of more than 6,000 volumes included works in Greek, Hebrew, Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish. Much of Browning’s education came from his well-read father. It is believed that he was already proficient at reading and writing by the age of five. A bright and anxious student, Browning learned Latin, Greek, and French by the time he was 14. From 14 to 16, he was educated at home, attended to by various tutors in music, drawing, dancing, and horsemanship. At the age of 12, he wrote a volume of Byronic verse entitled Incondita, which his parents attempted, unsuccessfully, to have published. In 1825, a cousin gave Browning a collection of Shelley’s poetry; Browning was so taken with the book that he asked for the rest of Shelley’s works for his 13th birthday, and declared himself a vegetarian and an atheist in emulation of the poet. Despite this early passion, he apparently wrote no poems between the ages of 13 and 20. In 1828, Browning enrolled at the University of London, but he soon left, anxious to read and learn at his own pace. The random nature of his education later surfaced in his writing, leading to criticism of his poems’ obscurities.

In 1833, Browning anonymously published his first major published work, Pauline, and in 1840 he published Sordello, which was widely regarded as a failure. He also tried his hand at drama, but his plays, including Strafford, which ran for five nights in 1837, and the Bells and Pomegranates series, were for the most part unsuccessful. Nevertheless, the techniques he developed through his dramatic monologues—especially his use of diction, rhythm, and symbol—are regarded as his most important contribution to poetry, influencing such major poets of the twentieth century as Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and Robert Frost.

After reading Elizabeth Barrett’s Poems (1844) and corresponding with her for a few months, Browning met her in 1845. They were married in 1846, against the wishes of Barrett’s father. The couple moved to Pisa and then Florence, where they continued to write. They had a son, Robert “Pen” Browning, in 1849, the same year Browning’s Collected Poems was published. Elizabeth inspired Robert’s collection of poems Men and Women (1855), which he dedicated to her. Now regarded as one of Browning’s best works, the book was received with little notice at the time; its author was then primarily known as Elizabeth Barrett’s husband.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in 1861, and Robert and Pen Browning moved to London soon after. Browning went on to publish Dramatis Personae (1863), and The Ring and the Book (1868). The latter, based on a 17th century Italian murder trial, received wide critical acclaim, finally earning Browning renown and respect in the twilight of his career. The Browning Society was founded while he still lived, in 1881, and he was awarded honorary degrees by Oxford University in 1882 and the University of Edinburgh in 1884. Robert Browning died on the same day that his final volume of verse, Asolando, was published, in 1889.

Reprinted with the permission of the Academy of American Poets, 75 Maiden Lane, Suite 901, New York, NY. www.poets.org.

7

Porphyria's Lover

Robert Browning

The rain set early in to-night,

The sullen wind was soon awake,

It tore the elm-tops down for spite,

And did its worst to vex the lake:

I listened with heart fit to break.

When glided in Porphyria; straight

She shut the cold out and the storm,

And kneeled and made the cheerless grate

Blaze up, and all the cottage warm;

Which done, she rose, and from her form

Withdrew the dripping cloak and shawl,

And laid her soiled gloves by, untied

Her hat and let the damp hair fall,

And, last, she sat down by my side

And called me. When no voice replied,

She put my arm about her waist,

And made her smooth white shoulder bare,

And all her yellow hair displaced,

And, stooping, made my cheek lie there,

And spread, o’er all, her yellow hair,

Murmuring how she loved me — she

Too weak, for all her heart’s endeavour,

To set its struggling passion free

From pride, and vainer ties dissever,

And give herself to me for ever.

But passion sometimes would prevail,

Nor could to-night’s gay feast restrain

A sudden thought of one so pale

For love of her, and all in vain:

So, she was come through wind and rain.

Be sure I looked up at her eyes

Happy and proud; at last I knew

Porphyria worshipped me; surprise

Made my heart swell, and still it grew

While I debated what to do.

That moment she was mine, mine, fair,

Perfectly pure and good: I found

A thing to do, and all her hair

In one long yellow string I wound

Three times her little throat around,

And strangled her. No pain felt she;

I am quite sure she felt no pain.

As a shut bud that holds a bee,

I warily oped her lids: again

Laughed the blue eyes without a stain.

And I untightened next the tress

About her neck; her cheek once more

Blushed bright beneath my burning kiss:

I propped her head up as before,

Only, this time my shoulder bore

Her head, which droops upon it still:

The smiling rosy little head,

So glad it has its utmost will,

That all it scorned at once is fled,

And I, its love, am gained instead!

Porphyria’s love: she guessed not how

Her darling one wish would be heard.

And thus we sit together now,

And all night long we have not stirred,

And yet God has not said a word!

—1836, 1842

8

My Last Duchess

Robert Browning

FERRARA

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. IThe Duke is based upon Alfonso II, fifth Duke of Ferrara (1533-97). In 1558, he married 14-year-old Lucrezia de’ Medici, who died in 1561 under suspicious circumstances. call

That piece a wonder, now; Fra PandolfBrother Pandolf, a fictitious painter from a monastic order.’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said

“Fra Pandolf ” by design, for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ’twas not

Her husband’s presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek; perhaps

Fra Pandolf chanced to say, “Her mantle laps

Over my lady’s wrist too much,” or “Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half-flush that dies along her throat.” Such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart—how shall I say?— too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Sir, ’twas all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace—all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men—good! but thanked

Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech—which I have not—to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, “Just this

Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark”—and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse—

E’en then would be some stooping; and I choose

Never to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will’t please you rise? We’ll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your master’s known munificence

Is ample warrant that no just pretense

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;

Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll go

Together down, sir. Notice NeptuneRoman sea god, here depicted as subduing a mythical beast, half horse, half fish., though,

Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of InnsbruckAn imaginary sculptor. The reference may be an indirect compliment to Frederick of Innsbruck, Count of Tyrol, whose daughter Alfonso married in 1565. cast in bronze for me!

—1842

9

The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church

Robert Browning

RomeThe Basilica of Santa Prassede, commemorating a virgin saint who gave her wealth to the poor, is in Rome. It has no tomb such as that imagined by Browning’s Bishop. 15–

Vanity, saith the preacher, vanity!cf. Ecclesiastes 1.2: “Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher...all is vanity.”

Draw round my bed: is AnselmOne of the bishop’s illegitimate sons, euphemistically referred to as “nephews.” keeping back?

Nephews — sons mine . . . ah God, I know not! Well —

She, men would have to be your mother once,

Old Gandolf envied me, so fair she was!

What’s done is done, and she is dead beside,

Dead long ago, and I am Bishop since,

And as she died so must we die ourselves,

And thence ye may perceive the world’s a dream.

Life, how and what is it? As here I lie 10

In this state-chamber, dying by degrees,

Hours and long hours in the dead night, I ask

“Do I live, am I dead?” Peace, peace seems all.

Saint Praxed’s ever was the church for peace;

And so, about this tomb of mine. I fought

With tooth and nail to save my niche, ye know:

— Old Gandolf cozened me, despite my care;

Shrewd was that snatch from out the corner South

He graced his carrion with. God curse the same!

Yet still my niche is not so cramped but thence 20

One sees the pulpit o’ the epistle-sideThe people’s right side of the altar from which the Epistle is read during Mass.,

And somewhat of the choir, those silent seats,

And up into the aery dome where live

The angels, and a sunbeam’s sure to lurk;

And I shall fill my slab of basalt there,

And ‘neath my tabernacleCanopy over a tomb. take my rest,

With those nine columns round me, two and two,

The odd one at my feet where Anselm stands:

Peach-blossom marble all, the rare, the ripe

As fresh-poured red wine of a mighty pulse. 30

— Old Gandolf with his paltry onion-stoneCheap marble.,

Put me where I may look at him! True peach,

Rosy and flawless: how I earned the prize!

Draw close: that conflagration of my church

— What then? So much was saved if aught were missed!

My sons, ye would not be my death? Go dig

The white-grape vineyard where the oil-press stood,

Drop water gently till the surface sink,

And if ye find . . . Ah God, I know not, I! . . .

Bedded in store of rotten fig-leaves soft, 40

And corded up in a tight olive-frail,

Some lump, ah God, of , lapis lazuliSemi-precious blue stone.,

Big as a Jew’s head cut off at the nape,

Blue as a vein o’er the Madonna’s breast . . .

Sons, all have I bequeathed you, villas, all,

That brave FrascatiA resort town near Rome. villa with its bath,

So, let the blue lump poise between my knees,

Like God the Father’s globe on both his hands

Ye worship in the Jesu Church so gay,

For Gandolf shall not choose but see and burst! 50

Swift as a weaver’s shuttlecf. Job 7.9: “My days are swifter than a weaver’s shuttle, and are spent without hope.” fleet our years:

Man goeth to the grave, and where is he?

Did I say basaltGreenish or brown-black rock often used for tombstones. for my slab, sons? Black —

‘T was ever antique-blackBlack stone, costlier than basalt. I meant! How else

Shall ye contrast my friezeA band of painted or sculpted decoration. to come beneath?

The bas-relief in bronze ye promised me,

Those Pans and NymphsPan, Greek god of the forest, often associated with sexual license. Nymphs are beautiful maidens. Here the bishop confuses the worldly with the spiritual, the pagan with the Christian, in his ideas for the bas-relief sculptures. ye wot of, and perchance

Some tripod, thyrsusOrnamented staff of Bacchus., with a vase or so,

The Saviour at his sermon on the mount,

Saint Praxed in a glory, and one Pan 60

Ready to twitch the Nymph’s last garment off,

And Moses with the tables . . . but I know

Ye mark me not! What do they whisper thee,

Child of my bowels, Anselm? Ah, ye hope

To revel down my villas while I gasp

Bricked o’er with beggar’s mouldy travertineLimestone.

Which Gandolf from his tomb-top chuckles at!

Nay, boys, ye love me — all of jasperTranslucent green quartz., then!

‘T is jasper ye stand pledged to, lest I grieve.

My bath must needs be left behind, alas! 70

One block, pure green as a pistachio-nut,

There’s plenty jasper somewhere in the world —

And have I not Saint Praxed’s ear to pray

Horses for ye, and brown Greek manuscripts,

And mistresses with great smooth marbly limbs?

— That’s if ye carve my epitaph aright,

Choice Latin, picked phrase, Tully’sMarcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC) Great Roman philosopher, linguist, and orator. every word,

No gaudy ware like Gandolf’s second line —

Tully, my masters? UlpianDomitius Ulpianus (AD 170-228). A Roman jurist whose style was considered inferior to that of Cicero. serves his need!

And then how I shall lie through centuries, 80

And hear the blessed mutter of the mass,

And see God made and eatenSlurring allusion to the doctrine of transubstantiation. all day long,

And feel the steady candle-flame, and taste

Good strong thick stupefying incense-smoke!

For as I lie here, hours of the dead night,

Dying in state and by such slow degrees,

I fold my arms as if they clasped a crook,

And stretch my feet forth straight as stone can pointThe tomb would be surmounted by a recumbent effigy of the occupant.,

And let the bedclothes, for a mortcloth, drop

Into great laps and folds of sculptor’s-work: 90

And as yon tapers dwindle, and strange thoughts

Grow, with a certain humming in my ears,

About the life before I lived this life,

And this life too, popes, cardinals and priests,

Saint Praxed at his sermon on the mountThe bishop confuses St. Praxed, a woman, with Christ, who gave the Sermon on the Mount.,

Your tall pale mother with her talking eyes,

And new-found agate urns as fresh as day,

And marble’s language, Latin pure, discreet,

— Aha, ELUCESCEBAT“He was illustrious,” the Ulpian Latin chosen for Gandolf’s tomb by the bishop. Ciceronian Latin would be “elucebat.” quoth our friend?

No Tully, said I, Ulpian at the best! 100

Evil and brief hath been my pilgrimage.cf. Genesis 47.9.

All lapis, all, sons! Else I give the Pope

My villas! Will ye ever eat my heart?

Ever your eyes were as a lizard’s quick,

They glitter like your mother’s for my soul,

Or ye would heighten my impoverished frieze,

Piece out its starved design, and fill my vase

With grapes, and add a vizor and a TermA vizor is the mask of a helmet; “Term” refers to a bust on a pedestal, erected to honour Terminus, the Roman god of boundaries.,

And to the tripod ye would tie a lynx

That in his struggle throws the thyrsus down, 110

To comfort me on my entablaturePlatform.

Whereon I am to lie till I must ask

“Do I live, am I dead?” There, leave me, there!

For ye have stabbed me with ingratitude

To death — ye wish it — God, ye wish it! Stone —

GritstoneCheap sandstone., a-crumble! Clammy squares which sweat

As if the corpse they keep were oozing through —

And no more lapis to delight the world!

Well go! I bless ye. Fewer tapers there,

But in a row: and, going, turn your backs 120

— Ay, like departing altar-ministrants,

And leave me in my church, the church for peace,

That I may watch at leisure if he leers —

Old Gandolf, at me, from his onion-stone,

As still he envied me, so fair she was!

—1845

10

Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister

Robert Browning

Gr-r-r—there go, my heart’s abhorrence!

Water your damned flower-pots, do!

If hate killed men, Brother Lawrence,

God’s blood, An archaic oath, often “’sblood”; similar to Gadzooks (God’s hooks) or Zounds (His wounds).would not mine kill you!

What? your myrtle-bush wants trimming?

Oh, that rose has prior claims—

Needs its leaden vase filled brimming?

Hell dry you up with its flames!

At the meal we sit together;

Salve tibi!Latin, “Hail to you.” All italicized words are those of Brother Lawrence. I must hear

Wise talk of the kind of weather,

Sort of season, time of year:

Not a plenteous cork crop: scarcely

Dare we hope oak-galls,Swellings on diseased oak leaves, yielding tannin, used in dyeing. I doubt;

What’s the Latin name for “parsley”?

What’s the Greek name for “swine’s snout”?Translation of the Latin—rostrum porcinum—for dandelion.

Whew! We’ll have our platter burnished,

Laid with care on our own shelf!

With a fire-new spoon we’re furnished,

And a goblet for ourself,

Rinsed like something sacrificial

Ere ‘tis fit to touch our chapsJaws, mouth.—

Marked with L. for our initial!

(He-he! There his lily snaps!)

Saint, forsooth! While brown Dolores

Squats outside the Convent bank

With Sanchicha, telling stories,

Steeping tresses in the tank,

Blue-black, lustrous, thick like horsehairs,

—Can’t I see his dead eye glow,

Bright as ‘twere a Barbary corsair’s?Pirate of Africa’s Barbary Coast of northern Africa, renowned for fierceness and lechery.

(That is, if he’d let it show!)

When he finishes refection,The taking of food and drink, refreshment.

Knife and fork he never lays

Cross-wise, to my recollection,

As do I, in Jesu’s praise.

I the Trinity illustrate,

Drinking watered orange pulp—

In three sips the ArianHeresy which denied the doctrine of the Trinity by asserting that the Son of God was a subordinate entity to God the Father. frustrate;

While he drains his at one gulp!

Oh, those melons! if he’s able

We’re to have a feast; so nice!

One goes to the Abbot’s table,

All of us get each a slice.

How go on your flowers? None double?

Not one fruit-sort can you spy?

Strange!—And I, too, at such trouble,

Keep them close-nipped on the sly!

There’s a great text in Galatians,cf. Galatians 5:19-21, which lists numerous mortal sins.

Once you trip on it, entails

Twenty-nine distinct damnations,

One sure, if another fails;

If I trip him just a-dying,

Sure of heaven as sure can be,

Spin him round and send him flying

Off to hell, a Manichee?A heretic. The Manichean holds that the universe is controlled by equally balanced forces of good and evil.The speaker hopes to trick Brother Lawrence into uttering such a heresy before Lawrence can recant.

Or, my scrofulous French novel

On grey paper with blunt type!

Simply glance at it, you grovel

Hand and foot in Belial’s The Devil’s grip. gripe;

If I double down its pages

At the woeful sixteenth print,

When he gathers his greengages,

Ope a sieve and slip it in’t?

Or, there’s Satan!—one might venture

Pledge one’s soul to him, yet leave

Such a flaw in the indentureThe speaker considers selling his soul to Satan in exchange for Lawrence’s damnation, but would leave a loophole through which he can escape damnation himself.

As he’d miss till, past retrieve,

Blasted lay that rose-acacia

We’re so proud of! Hy, Zy, Hine…Probably the opening words of a curse against Lawrence.

‘St, there’s Vespers! Plena gratia

Ave, Virgo! “Full of grace; Hail, Virgin!” Gr-r-r—you swine!

—1842

11

Study Questions, Activities, and Resources

Study Questions and Activities

Porphyria’s Lover

- Why does the speaker murder Porphyria?

- Read the following essay, which argues that Shakespeare’s Othello is another source for Browning’s “Porphyria’s Lover.” http://www.cswnet.com/~erin/rb6.htm

My Last Duchess

- What is the rhyme scheme in this poem?

- Give some examples of enjambment in the poem. What purpose does enjambment serve in this poem?

- What is the dramatic situation in the poem? Who is speaking and to whom?

- Is there any dramatic movement in the poem?

- What were the duchess’s alleged faults?

- How does Browning engage our sympathies for the duchess?

Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister

- What is the speaker’s dominant characteristic?

- What is the main characteristic of Brother Lawrence?

- In what way might Browning have used Friar Lawrence in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet to characterize his own Brother Lawrence?

The Bishop Orders His Tomb

- Who is Anselm?

- Is Browning criticizing aspects of 16th century Roman culture?

- Of what sins is the bishop guilty?

- Why is the choice of St. Praxed as the site of this bishop’s tomb ironic?

- List a few appropriately conventional sentiments uttered by the bishop.

- List some surprisingly unconventional sentiments he utters.

- How do you explain line 95: “St. Praxed at his sermon on the mount”?

Essay topics

Write an essay of 1,000 to 1,500 words on irony in “My Last Duchess,” “Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister,” and “The Bishop Orders His Tomb.”

Philip Allingham notes, “Browning is noted as a writer of Dramatic Monologues, in which a single ‘actor’ or persona (rather than the poet) speaks to an implied auditor and is, as it were, overheard by the reader (who has no authorial comment to shape his or her interpretation of the characters and their circumstances).” However, this poem is called a entitled a “soliloquy.” What features of “Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister” render the poem a soliloquy rather than a dramatic monologue? In particular, who is the poem’s “implied auditor”? Please refer to a good glossary of literary terms, and then in an essay of 1,000 to 1500 words, discuss any two of “My Last Duchess,” “Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister,” and “The Bishop Orders His Tomb” as dramatic monologues.

Compare any one of Browning’s dramatic monologues to one by Donne, such as “The Flea” or “The Canonization.” http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/donne/flea.php

Resources

Film Treatments:

The Bishop Orders His Tomb

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-lN48Xzh70

Porphyria’s Lover

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rWiPuE1zjuo

Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1SlZidobhM

Resources

http://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/poetryperformance/browning/josephinehart/aboutbrowning.html

References

Figure 1:

Robert Browning 1865 by Julia Margaret Cameron (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Robert_Browning_1865.jpg) is in the Public Domain

IV

Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892)

12

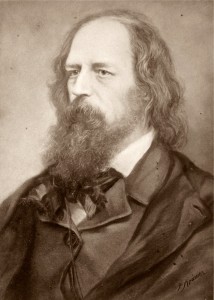

Biography

Born on August 6, 1809, in Somersby, Lincolnshire, England, Alfred Tennyson is one of the best-loved Victorian poets. Tennyson, the fourth of 12 children, showed an early talent for writing. At the age of 12 he wrote a 6,000-line epic poem. His father, the Reverend George Tennyson, tutored his sons in classical and modern languages. In the 1820s, however, Tennyson’s father began to suffer frequent mental breakdowns that were exacerbated by alcoholism. One of Tennyson’s brothers had violent quarrels with his father, a second was later confined to an insane asylum, and another became an opium addict.

Tennyson escaped home in 1827 to attend Trinity College, Cambridge. In that same year, he and his brother Charles published Poems by Two Brothers. Although the poems in the book were mostly juvenilia, they attracted the attention of the “Apostles,” an undergraduate literary club led by Arthur Hallam. The Apostles provided Tennyson, who was tremendously shy, with much needed friendship and confidence as a poet. Hallam and Tennyson became the best of friends; they toured Europe together in 1830 and again in 1832. Hallam’s sudden death in 1833 greatly affected the young poet. The long elegy In Memoriam and many of Tennyson’s other poems are tributes to Hallam.

In 1830, Tennyson published Poems, Chiefly Lyrical, and in 1832 he published a second volume entitled simply Poems. Some reviewers condemned these books as “affected” and “obscure.” Tennyson, stung by the reviews, would not publish another book for nine years. In 1836, he became engaged to Emily Sellwood, but when he lost his inheritance on a bad investment in 1840, Sellwood’s family called off the engagement. In 1842, however, Tennyson’s Poems in two volumes was a tremendous critical and popular success. In 1850, with the publication of In Memoriam, Tennyson became one of Britain’s most popular poets. He was selected Poet Laureate in succession to Wordsworth. In that same year, he finally married Emily Sellwood. They had two sons, Hallam and Lionel.

At the age of 41, Tennyson had established himself as the most popular poet of the Victorian era. The money from his poetry (at times exceeding 10,000 pounds per year) allowed him to purchase a house in the country and to write in relative seclusion. His physical appearance—he was a large and bearded man and he regularly wore a cloak and a broad-brimmed hat—enhanced his notoriety. He read his poetry with a booming voice, which was often compared to that of Dylan Thomas In 1859, Tennyson published the first poems of Idylls of the Kings, which sold more than 10,000 copies in one month. In 1884 he accepted a peerage, becoming Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Tennyson died on October 6, 1892, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Reprinted with the permission of the Academy of American Poets, 75 Maiden Lane, Suite 901, New York, NY. www.poets.org.

13

The Lady of Shalott

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Part I

On either side the river lie

Long fields of barley and of rye,

That clothe the woldA plain. and meet the sky;

And through the field the road runs by

To many-towered Camelot;

And up and down the people go,

Gazing where the lilies blowBloom.

Round an island there below,

The island of Shalott.

Willows whitenThe white underside of the willow leaves are lifted by the wind. , aspens quiver,

Little breezes dusk and shiver

Through the wave that runs for ever

By the island in the river

Flowing down to Camelot.

Four grey walls, and four grey towers,

Overlook a space of flowers,

And the silent isle imbowers

The Lady of Shalott.

By the margin, willow-veiled,

Slide the heavy barges trailed

By slow horses; and unhailed

The shallopA small, open boat propelled by oars or sails and used mainly in shallow waters. flitteth silken-sailed

Skimming down to Camelot:

But who hath seen her wave her hand?

Or at the casement seen her stand?

Or is she known in all the land,

The Lady of Shalott?

Only reapers, reaping early

In among the bearded barley,

Hear a song that echoes cheerly

From the river winding clearly,

Down to towered Camelot:

And by the moon the reaper weary,

Piling sheaves in uplands airy,

Listening, whispers “‘Tis the fairy

Lady of Shalott.”

Part II

There she weaves by night and day

A magic web with colours gay.

She has heard a whisper say,

A curse is on her if she stayPause.

To look down to Camelot.

She knows not what the curse may be,

And so she weaveth steadily,

And little other care hath she,

The Lady of Shalott.

And moving through a mirrorAt her loom, the lady faces the back of her tapestry, and weaves by consulting a mirror in which the design is reflected. clear

That hangs before her all the year,

Shadows of the world appear.

There she sees the highway near

Winding down to Camelot:

There the river eddy whirls,

And there the surly village-churlsPeasants.,

And the red cloaks of market girls,

Pass onward from Shalott.

Sometimes a troop of damsels glad,

An abbot on an ambling pad,

Sometimes a curly shepherd-lad,

Or long-haired page in crimson clad,

Goes by to towered Camelot;

And sometimes through the mirror blue

The knights come riding two and two:

She hath no loyal knight and true,

The Lady of Shalott.

But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror’s magic sights,

For often through the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, went to Camelot:

Or when the moon was overhead,

Came two young lovers lately wed;

“I am half sick of shadows,” said

The Lady of Shalott.

Part III

A bow-shot from her bower-eaves,

He rode between the barley-sheaves,

The sun came dazzling through the leaves,

And flamed upon the brazen greavesArmour for the leg below the knee.

Of bold Sir Lancelot.

A red-cross knight for ever kneeled

To a lady in his shield,

That sparkled on the yellow field,

Beside remote Shalott.

The gemmy bridle glittered free,

Like to some branch of stars we see

Hung in the golden Galaxy.

The bridle bells rang merrily

As he rode down to Camelot:

And from his blazoned baldricA belt worn over one shoulder to support a sword or bugle. slung

A mighty silver bugle hung,

And as he rode his armour rung,

Beside remote Shalott.

All in the blue unclouded weather

Thick-jewelled shone the saddle-leather,

The helmet and the helmet-feather

Burned like one burning flame together,

As he rode down to Camelot.

As often through the purple night,

Below the starry clusters bright,

Some bearded meteor, trailing light,

Moves over still Shalott.

His broad clear brow in sunlight glowed;

On burnished hooves his war-horse trode;

From underneath his helmet flowed

His coal-black curls as on he rode,

As he rode down to Camelot.

From the bank and from the river

He flashed into the crystal mirror,

“Tirra lirraIn Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, (4.3: 11-12), Autolycus sings about “tumbling in the hay” with his “aunts” (whores).,” by the river

Sang Sir Lancelot.

She left the web, she left the loom,

She made three paces through the room,

She saw the water-lily bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume,

She looked down to Camelot.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror cracked from side to side;

“The curse is come upon me,” cried

The Lady of Shalott.

Part IV

In the stormy east-wind straining,

The pale yellow woods were waning,

The broad stream in his banks complaining,

Heavily the low sky raining

Over towered Camelot;

Down she came and found a boat

Beneath a willow left afloat,

And round about the prow she wrote

The Lady of Shalott.

And down the river’s dim expanse,

Like some bold seër in a trance

Seeing all his own mischance—

With a glassy countenance

Did she look to Camelot.

And at the closing of the day

She loosed the chain, and down she lay;

The broad stream bore her far away,

The Lady of Shalott.

Lying, robed in snowy white

That loosely flew to left and right—

The leaves upon her falling light—

Through the noises of the night

She floated down to Camelot:

And as the boat-head wound along

The willowy hills and fields among,

They heard her singing her last song,

The Lady of Shalott.

Heard a carol, mournful, holy,

Chanted loudly, chanted lowly,

Till her blood was frozen slowly,

And her eyes were darkened wholly,

Turned to towered Camelot.

For ere she reached upon the tide

The first house by the water-side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott.

Under tower and balcony,

By garden-wall and gallery,

A gleaming shape she floated by,

Dead-pale between the houses high,

Silent into Camelot.

Out upon the wharfs they came,

Knight and burgher, lord and dame,

And round the prow they read her name,

The Lady of Shalott.

Who is this? and what is here?

And in the lighted palace near

Died the sound of royal cheer;

And they crossed themselves for fear,

All the knights at Camelot:

But Lancelot mused a little space;

He said, “She has a lovely face;

God in his mercy lend her grace,

The Lady of Shalott.”

—1832, 1842

14

From the Princess

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

‘Blame not thyself too much,’ I said, ‘nor blame

Too much the sons of men and barbarous laws;

These were the rough ways of the world till now.

Henceforth thou hast a helper, me, that know

The woman’s cause is man’s: they rise or sink

Together, dwarfed or godlike, bond or free:

For she that out of Lethe scales with man

The shining steps of Nature, shares with man

His nights, his days, moves with him to one goal,

Stays all the fair young planet in her hands—

If she be small, slight-natured, miserable,

How shall men grow? but work no more alone!

Our place is much: as far as in us lies

We two will serve them both in aiding her—

Will clear away the parasitic forms

That seem to keep her up but drag her down—

Will leave her space to burgeon out of all

Within her—let her make herself her own

To give or keep, to live and learn and be

All that not harms distinctive womanhood.

For woman is not undevelopt man,

But diverse: could we make her as the man,

Sweet Love were slain: his dearest bond is this,

Not like to like, but like in difference.

Yet in the long years liker must they grow;

The man be more of woman, she of man;

He gain in sweetness and in moral height,

Nor lose the wrestling thews that throw the world;

She mental breadth, nor fail in childward care,

Nor lose the childlike in the larger mind;

Till at the last she set herself to man,

Like perfect music unto noble words;

And so these twain, upon the skirts of Time,

Sit side by side, full-summed in all their powers,

Dispensing harvest, sowing the To-be,

Self-reverent each and reverencing each,

Distinct in individualities,

But like each other even as those who love.

Then comes the statelier Eden back to men:

Then reign the world’s great bridals, chaste and calm:

Then springs the crowning race of humankind.

May these things be!’

Sighing she spoke ‘I fear

They will not.’

‘Dear, but let us type them now

In our own lives, and this proud watchword rest

Of equal; seeing either sex alone

Is half itself, and in true marriage lies

Nor equal, nor unequal: each fulfils

Defect in each, and always thought in thought,

Purpose in purpose, will in will, they grow,

The single pure and perfect animal,

The two-celled heart beating, with one full stroke,

Life.’

And again sighing she spoke: ‘A dream

That once was mind! what woman taught you this?’

—1847

15

The Lotos-Eaters

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

This poem is based on Homer’s Odyssey, Chapter 9, which describes a visit by Ulysses and his men to the home of the Lotos-eaters (also “lotus”) on their way home from the Trojan War. Those who ate of the honey-sweet fruit of the lotos tree became indolent and forgot their home.

“Courage!” heOdysseus, legendary Greek king of Ithaca, known also by his Roman name Ulysses. said, and pointed toward the land,

“This mounting wave will roll us shoreward soon.”

In the afternoon they came unto a land

In which it seemed always afternoon.

All round the coast the languid air did swoon,

Breathing like one that hath a weary dream.

Full-faced above the valley stood the moon;

And like a downward smoke, the slender stream

Along the cliff to fall and pause and fall did seem.

A land of streams! some, like a downward smoke,

Slow-dropping veils of thinnest lawnSheer linen., did go;

And some thro’ wavering lights and shadows broke,

Rolling a slumbrous sheet of foam below.