Epic historical novel digs deep into Zionism’s less probed Western European roots

In ‘The Wealthy,’ Israeli author Hamutal Bar-Yosef uses 200-year saga of fictional German-Anglo Jewish family to highlight different take on how the Jewish state came to be

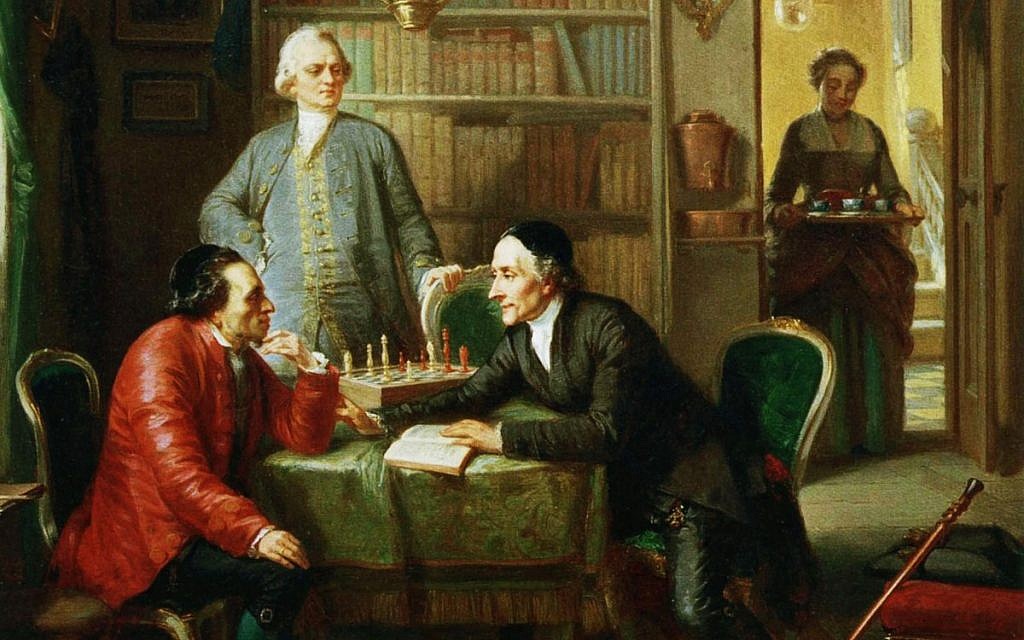

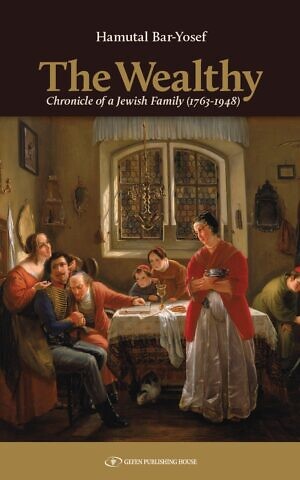

An 'Enlightenment' scene with guests in the home of Moses Mendelssohn, by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, 1856. (Public domain)

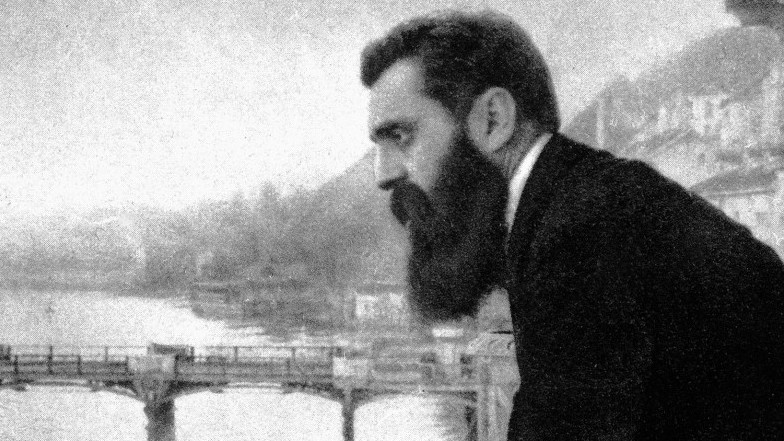

An 'Enlightenment' scene with guests in the home of Moses Mendelssohn, by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, 1856. (Public domain) Theodor Herzl on the balcony of the Hotel Les Trois Rois in Basel, Switzerland, 1897. (CC-PD-Mark, by Wikigamad, Wikimedia Commons)

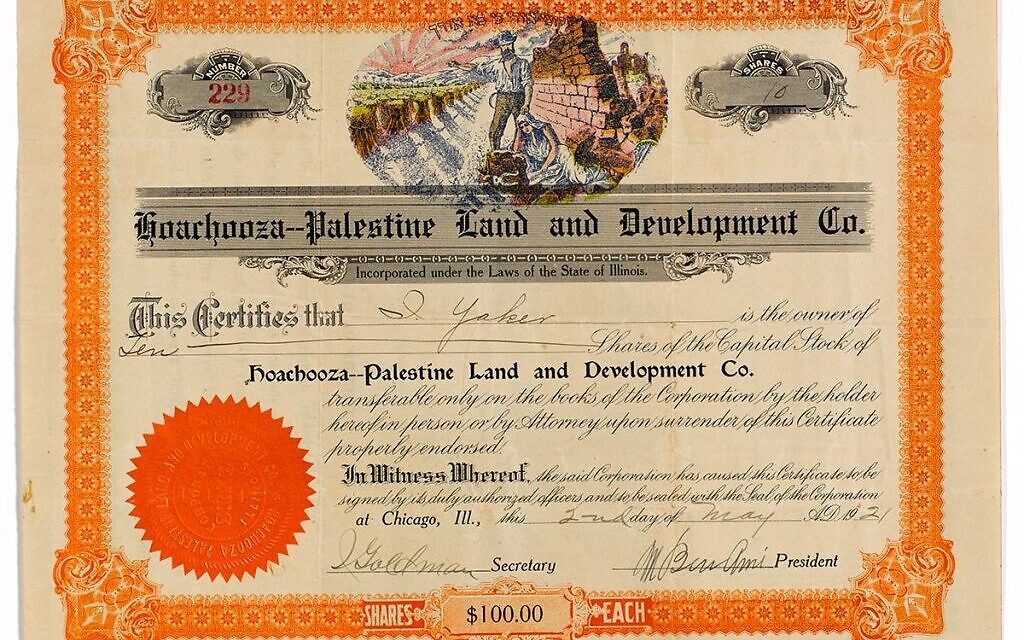

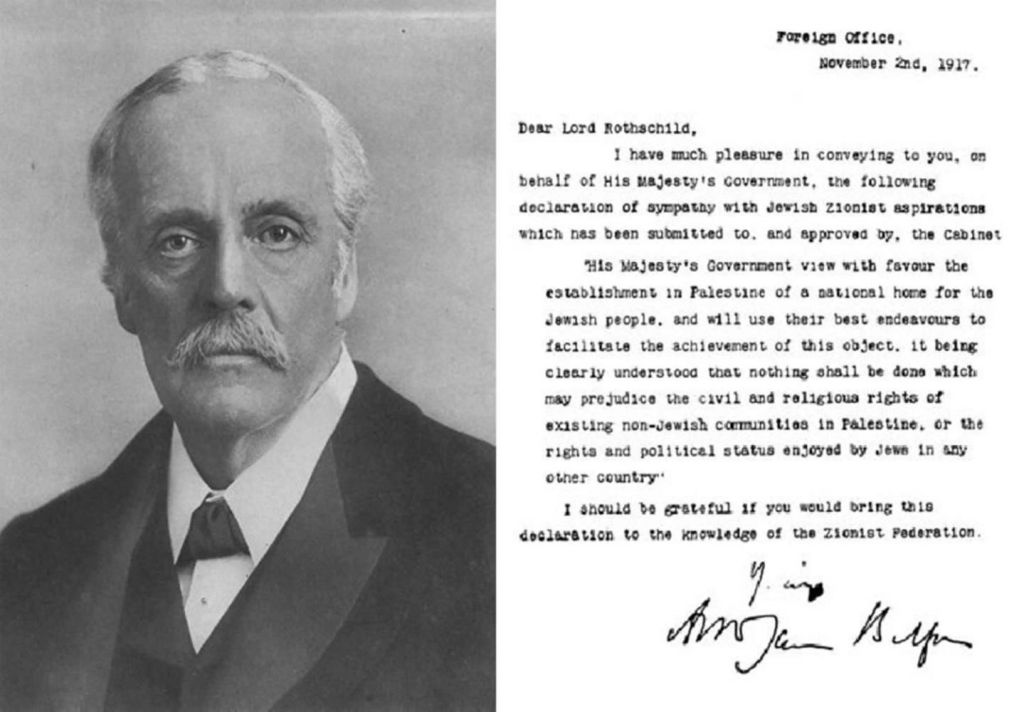

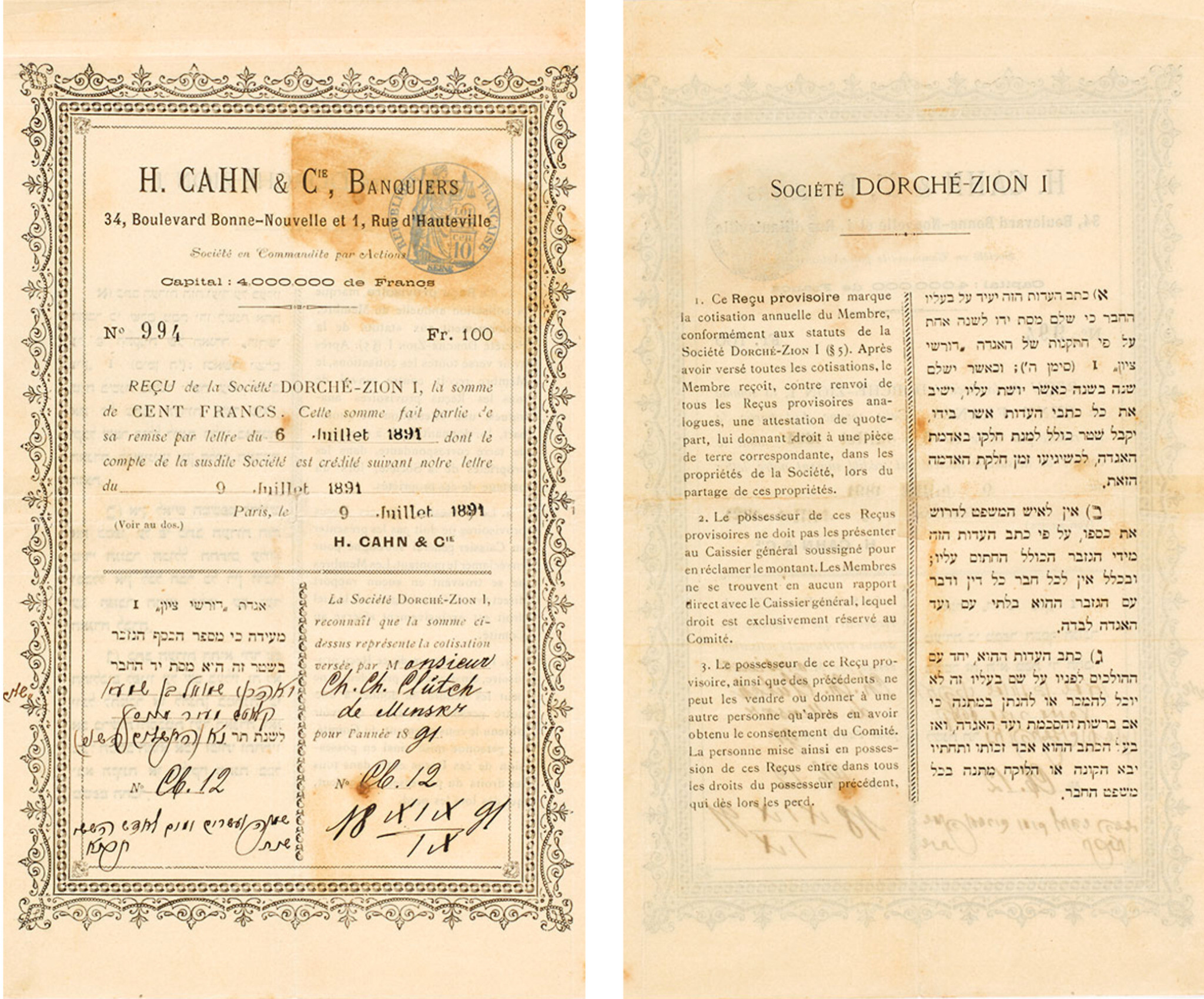

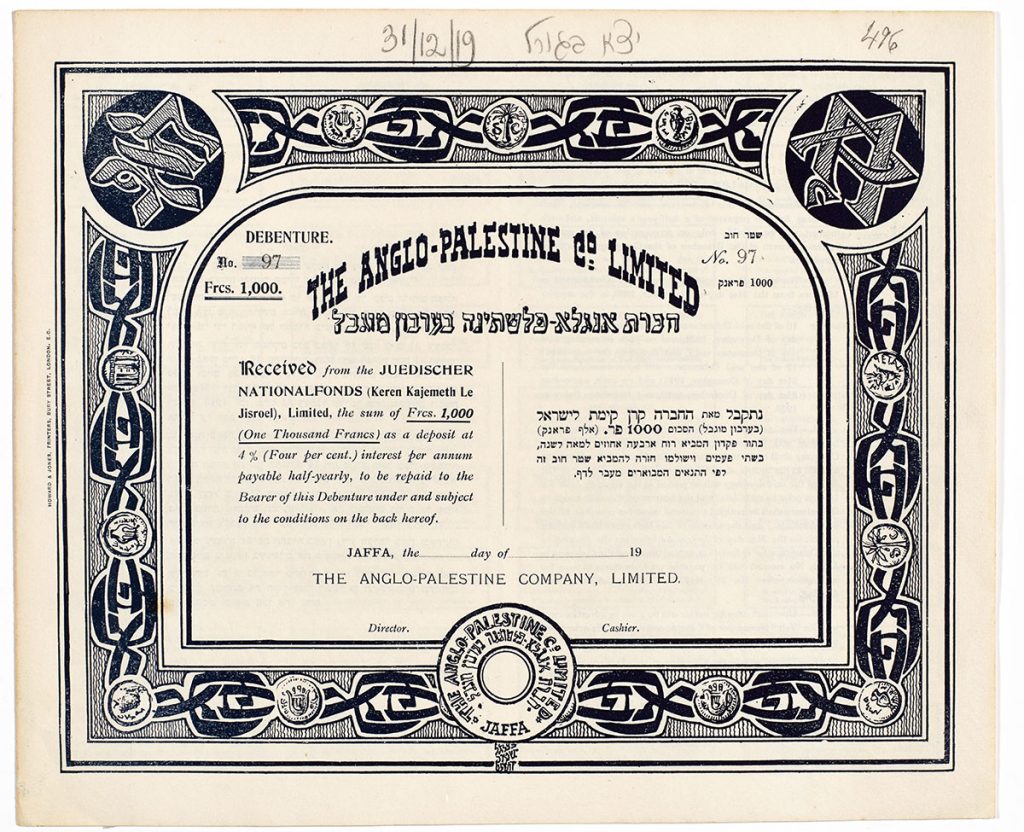

Theodor Herzl on the balcony of the Hotel Les Trois Rois in Basel, Switzerland, 1897. (CC-PD-Mark, by Wikigamad, Wikimedia Commons) 1921 Hoachooza - Palestine Land and Development Co. share certificate from Chicago. (Courtesy of David Matlow Collection)

1921 Hoachooza - Palestine Land and Development Co. share certificate from Chicago. (Courtesy of David Matlow Collection) Chaim Weizmann (left of center) at a meeting with Arab leaders at the King David Hotel, Jerusalem, 8 April 1933. The picture was taken the eve of Passover 1931 at discussions on land sale in Transjordan (Wikipedia)

Chaim Weizmann (left of center) at a meeting with Arab leaders at the King David Hotel, Jerusalem, 8 April 1933. The picture was taken the eve of Passover 1931 at discussions on land sale in Transjordan (Wikipedia)

Hamutal Bar-Yosef, 82, was fed up with the State of Israel’s legitimacy being questioned or attacked.

“As an Israeli, I am insulted and angry when I am called upon to justify the existence of my country,” said Bar-Yosef, a retired literature professor, and accomplished poet, short story writer and translator.

The octogenarian’s response was to write her first-ever novel, a 474-page epic. The tome makes the case for Zionism and Israel as it spans two centuries of the lives of members of a Western European Jewish family in three countries on two continents.

“The Wealthy: Chronicle of a Jewish Family (1763-1948)” was originally published in Hebrew as “Ha’ashirim” in 2017. The English translation by Esther Cameron came out earlier this year.

In an interview from her home in Jerusalem, Bar-Yosef explained her motivations behind the extensively researched novel about a fictional family, but populated with many actual historical figures.

“I wanted to write about Zionism and the birth of the State of Israel from an angle not usually emphasized, one that many aren’t aware of,” Bar-Yosef said.

“When I was growing up, we learned in school about the Holocaust, the pogroms, and the young Eastern European socialist halutzim [pioneers] who came [in the late 19th and early 20th century] to work the land, and who founded the kibbutzim. But that is not the whole story,” she said.

In her novel, Bar-Yosef examines the reasons why Zionism was attractive to a segment of 19th- and early 20th-century Western European Jews, as well. She shows how it was these Jews, with their devoted efforts and financial resources, who made the land purchases in Ottoman and British Mandate Palestine that gave modern Jews a significant and critical foothold in their ancient homeland.

Without these facts on the ground, the fledgling state of Israel would not have had a base from which to defend itself from invading Arab armies during the 1948 War of Independence.

Bar-Yosef’s novel is divided into three sections, taking place consecutively in Germany, England and the Land of Israel (pre-state Israel under British rule). The narrative, however, does not commence in any of these places.

It begins with a Jew in what is to become the Russian empire’s Pale of Settlement. His name is Meyer Heimstatt, and he lives in Brisk (today Brest in Belarus). Marrying in 1763 at age 13 to avoid military conscription, Meyer finds himself standing under the wedding canopy next to a girl he doesn’t know.

Meyer, a peddler, loses this wife when she dies in childbirth, and a second who wastes away from grief when their son is conscripted and killed in the Napoleonic Wars. By this time, the family is living in Trendelburg, near the Prussian city of Kassel.

Meyer marries a third time and has a son named Albert. Thus begins the family’s century-long sojourn in Germany.

As the story moves beyond the life of the poor, uneducated, religiously traditional Meyer, it becomes incrementally clear how the Heimstatt family saga is connected to Bar-Yosef’s defense of Zionism and the creation of Israel.

Meyer’s descendants are models for the progression of Western European Jews from poverty to prosperity — and assimilation — as they embrace the advancements brought by the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution.

But the achievement of equal civil rights in Western democracies did not make these Jews immune from deep-rooted, age-old antisemitism. Unlike violent attacks against Jews perpetrated in Eastern Europe, this was “soft” Jew-hatred, but it was Jew-hatred nonetheless. Eventually, some of these Jews turned to Zionism as a solution to what Zionism founder Theodor Herzl referred to as “the Jewish Question.”

As the story advances, Albert Heimstatt comes under the wing of a Jewish family of cloth merchants in Kassel. He marries one of their daughters and eventually takes over the business, making it more successful through expansion and innovation.

Albert’s wife introduces him to European culture — music, art, languages, museums — but he continues to live according to the Jewish laws.

The couple’s son Gotthold grows up in a period when the German government says it will give Jews equality only if they renounce their particular customs and traditions. Albert believes that wealth and education are key for the Jews to flourish, so he sends Gotthold to the University of Heidelberg to study chemistry, a subject for which he has a natural affinity.

However, after his first year, Gotthold comes home with a dueling scar down his cheek and a flunking grade in Latin. He doesn’t want to stay in university, and would rather apprentice with his maternal uncle in Cologne, who does chemistry for manufacturing. Gotthold is particularly interested in investigating how to clean up the environment by developing positive and safe uses for industrial byproducts.

Consummating a years-long love for his much younger cousin Minna, Gotthold marries her when she turns 19. Although no date is given for the wedding, the narrative hints that it is 1866, the year of the Austro-Prussian War, the second war of German unification under Bismarck.

The families hope that Bismarck will win the war, as they believe that German unification will bring about equal rights for the Jews.

“We are German in every respect. We just have different holidays and a few different religious customs,” the bride’s father says.

Author Bar-Yosef explained that the Germans were not particularly enthused about granting full rights to the Jews.

“I read through 50 years of debates during the period between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the unification under Bismarck [in 1871], and they revealed to me deep-rooted antisemitism,” she said.

By the time Minna gives birth to a son named Richard in 1868, she and Gotthold have moved to the north of England for better business opportunities. Gotthold chooses not to have his son ritually circumcised.

Gotthold becomes a major chemical manufacturer with operations in Britain and other countries, but it doesn’t protect his family from prejudice. When faced with antisemitism at school, Richard is confused about his identity.

“But I am not Jewish,” he protests. “My parents aren’t really Jewish either. They don’t go to synagogue… My parents didn’t do circumcision on me.”

Gotthold and Minna eventually move to London, and Richard studies at Cambridge, focusing on law and politics. While at Cambridge, he and a friend speak about their desire to be completely accepted as English. They are aware of Herzl’s political Zionism, and of Baron Edmund de Rothschild‘s funding of agricultural colonies for Russian and Romanian Jews in the Land of Israel, but they don’t agree with the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

“After we have finally gotten out of the ghetto — should we go back to a Jewish ghetto in Palestine? I feel that Jews have a special talent for adjusting to any country where they live and becoming just like the inhabitants of the country,” Richard says.

Richard marries Violette, a Christian of Huguenot descent, in a church. Richard is elected to parliament while expanding the family manufacturing business. The couple raises their children Claire and Ralph as Christians.

As Claire and Ralph become young adults during World War I, “The Wealthy” shifts focus from England to the Land of Israel. After a long journey away from Judaism, the Heimstatts reconnect to it through Zionism as the answer to the world’s oldest hatred.

Bar-Yosef said she was surprised to learn through her research how xenophobic English society was in the World War I era. She illustrates this point in the novel by the baseless accusations of war profiteering aimed at Richard who, as a loyal government minister, works day and night to procure materials for the military.

Richard meets World Zionist Organization president Chaim Weizmann, and becomes a supporter of Zionism. He makes major financial contributions and fundraises from others. But he is not a fan of efforts by the Jewish National Fund (JNF) to buy land in Palestine in trust for the Jewish people. He is a firm believer in private ownership and buys his own plot for an agricultural settlement, and plans to build a villa on it for his retirement.

Richard’s daughter Claire, who marries a Jew, sometimes joins her father on Zionist fundraising trips to America. Son Ralph arrives in Palestine as a British soldier, and decides to stay — first as a British Mandate administrator, and then as a founder of “Heimstatt Hill,” a fictional settlement reminiscent of Petah Tikva.

This final section of the novel deals with the complex relations between Jews, absent effendis (wealthy Arab land owners), fellahin (Arab tenant farmers), and Bedouin with regard to the selling and purchasing of land in Palestine between 1917 and 1948.

“I learned a lot about this from oral histories of Jews who bought or helped buy lands from Arabs in the British Mandate period held at the Hebrew University,” Bar-Yosef said.

She gained an understanding of the economic factors driving the effendis to sell, and the Zionists to buy. Jews were ideologically motivated, but buying land in Palestine was also a good financial investment.

“The Wealthy” is a novel of descriptions and dialogue. Characters do not share their inner thoughts, and the narrative voice does not pass any judgments. The author herself characterized the book’s style as “dry” and “unemotive.”

“I am representing historical processes with this novel,” Bar-Yosef stated.

The historical detail in “The Wealthy” makes up for the lack of emotional drama. The book is the author’s chosen way to defend her country and argue that Jews living in Western democracies were — and still are — in need of a Jewish homeland in Israel as much as Jews from other parts of the world.

Moreover, if it were not for well-connected, educated and wealthy Western Jews like the fictional Heimstatts getting behind Zionism, real history could have turned out differently.

This article contains affiliate links. If you use these links to buy something, The Times of Israel may earn a commission at no additional cost to you.

Are you relying on The Times of Israel for accurate and timely coverage right now? If so, please join The Times of Israel Community. For as little as $6/month, you will:

- Support our independent journalists who are working around the clock;

- Read ToI with a clear, ads-free experience on our site, apps and emails; and

- Gain access to exclusive content shared only with the ToI Community, including exclusive webinars with our reporters and weekly letters from founding editor David Horovitz.

We’re really pleased that you’ve read X Times of Israel articles in the past month.

That’s why we started the Times of Israel eleven years ago - to provide discerning readers like you with must-read coverage of Israel and the Jewish world.

So now we have a request. Unlike other news outlets, we haven’t put up a paywall. But as the journalism we do is costly, we invite readers for whom The Times of Israel has become important to help support our work by joining The Times of Israel Community.

For as little as $6 a month you can help support our quality journalism while enjoying The Times of Israel AD-FREE, as well as accessing exclusive content available only to Times of Israel Community members.

Thank you,

David Horovitz, Founding Editor of The Times of Israel