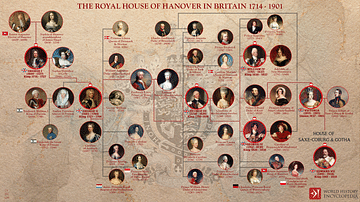

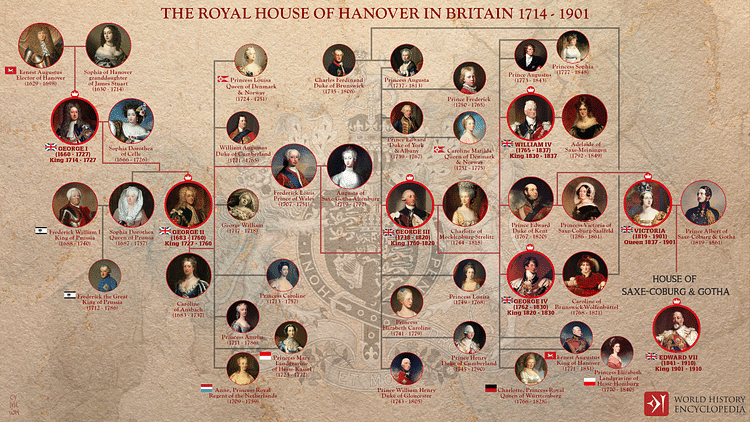

George I of Great Britain (r. 1714-1727) succeeded the last of the Stuart monarchs, Queen Anne of Great Britain (r. 1702-1714) because he was Anne's nearest Protestant relative. The House of Hanover secured its position as the new ruling family by defeating several Jacobite rebellions which supported the old Stuart line.

King George may have struggled with both English and the English, often preferring his attachments in Germany, but his reign was a relatively stable one. His greatest legacy was as a patron of the arts, in particular, his support of musicians like Handel and such lasting cultural institutions as the Royal Academy of Music. He was succeeded by his son George II of Great Britain (r. 1727-1760).

Succession: The House of Hanover

The Glorious Revolution of 1688 saw the end of the reign of the male Stuarts and placed William, Prince of Orange on the throne as William III of England (r. 1689-1702) with his wife, the daughter of the exiled James II of England (r. 1685-1688), made Mary II of England (r. 1689-1694). Mary's sister became the ruling monarch in 1702 as Anne, Queen of Great Britain. When Anne died, so ended the Stuart royal line, which had begun with Robert II of Scotland (r. 1371-1390).

Queen Anne outlived her husband Prince George of Denmark (1653-1708) by six years; she died at the age of 49 on 1 August 1714 at Kensington Palace after suffering two strokes. Queen Anne had had many children, but all died in infancy. The greatest hope for an heir had been William, Duke of Gloucester (b. 1689), but he died in 1700, aged 12. Anne's official heirs, the Hanoverian family, were selected as such in the 1701 Act of Settlement.

The Hanovers were connected to the British royal line as descendants of Elizabeth Stuart (d. 1662), daughter of James I of England (r. 1603-1625) and brief Queen of Bohemia through her husband Frederick V of the Palatinate. The chosen successor – although she was not permitted by Anne to even visit England – was Elizabeth Stuart's daughter Sophia (l. 1630-1714), wife of the Duke of Brunswick and Elector of Hanover (a small principality in Germany the size of Yorkshire). Sophie of Hanover was Queen Anne's nearest relation of the Protestant faith, a vital consideration given that Parliament had already passed a law forbidding a Catholic to take the throne. For this reason, more than 50 other claimants to the throne had been deemed unsuitable. When Sophia died in 1714, her son, George Ludwig, took over the role of heir apparent to the British throne.

Early Life & Family

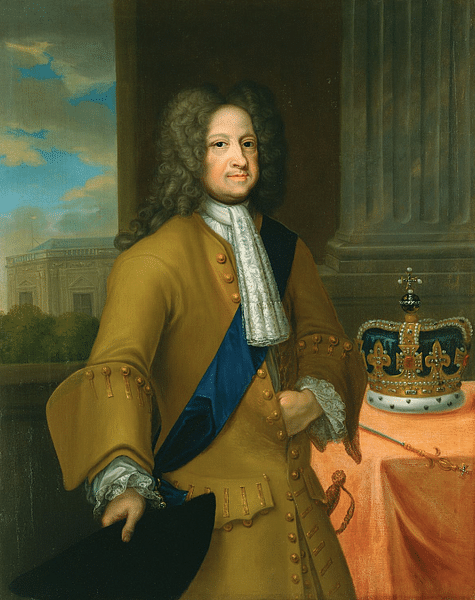

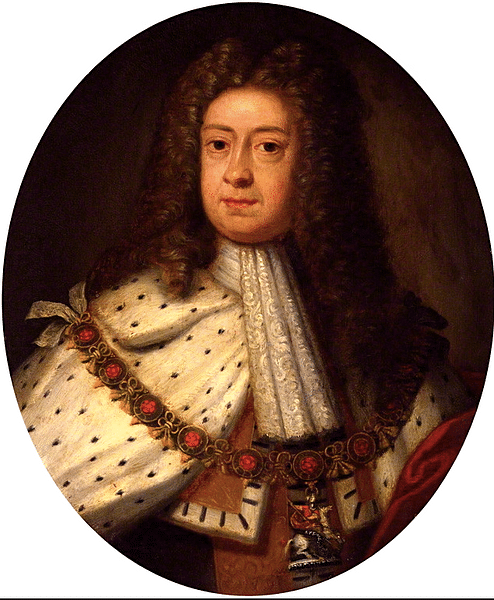

Georg Ludwig (he later anglicized his first name) was born on 28 May 1660 at Osnabrück in Lower Saxony, Germany. His father was Ernst August, Duke of Brunswick and Elector of Hanover, and his mother was Sophia Stuart, daughter of Frederick, Elector Palatine. George inherited his late father's title on 23 January 1698. George was a Lutheran, and he gained military and diplomatic experience defending the interests of Hanover. His character is described by one historian as "solid and uncommunicative, handicapped by a modest command of English, and set in his ways" (Cannon, 315). C. Philips is just as negative: "He was short, overweight, bad-tempered and lacking in both manners and charm" (176).

On 22 November 1682, as arranged by his father, George married his cousin Sophia Dorothea of Celle (l. 1666-1726), the daughter of Georg Wilhelm, Duke of Lüneburg-Celle in Germany. The couple went on to have two children: Georg August (b. 1683) and Sophia Dorothea. The couple's daughter went on to become queen in Prussia through marriage. Never really a true love match, George senior and Sophia divorced in December 1694 after it was discovered the latter had been conducting an affair with the Swedish nobleman, Count Philip von Königsmarck. The count mysteriously disappeared, and Sophia was banished for the rest of her life to Ahlden House in Celle, where she was no longer permitted any contact with her children. George had one notable mistress, Melusine von der Schulenburg (l. 1667-1743), who he had made the duchess of Kendal in 1719. It is possible the couple secretly married, but in any case, Melusine was treated as the king's wife at court. The couple had three illegitimate daughters. Another of the king's regular mistresses was Charlotte Sophia Kellmanns, who was maliciously rumoured to be George's half-sister.

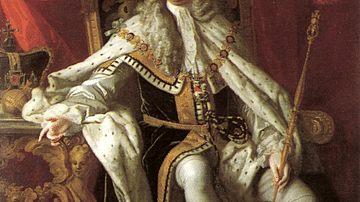

On 1 August 1714, having only ever visited England once (around 1680), George became King George I of Great Britain and Ireland. He was, at 54 years old, the oldest monarch to ever take the throne. There was no immediate and organised opposition to this switch of royal houses. George's coronation was held in Westminster Abbey on 20 October 1714, but there was to be one challenge to his throne the next year.

The Jacobite Rebellions

Notwithstanding the official selection or the prohibition of a Catholic on the throne, there was a serious challenge to George's succession in 1715. The Jacobites were those who supported the claim to the British throne through James II's exiled son James Francis Edward Stuart (1688-1766), also known as the Old Pretender (from the French word pretendant, meaning 'claimant'). The man who would be king refused to renounce his Catholicism to make himself more appealing to his prospective subjects, he was not the most inspiring of leaders anyway, and war-weary France was, for once, uninterested in getting involved in British affairs. As a consequence of these weaknesses, the Jacobite rising proved a damp squib of an event and was duly quashed in Scotland at the Battle of Preston on 14 November 1715 before the Old Pretender even reached Scotland. The Old Pretender spent a dismal six weeks enduring a Scottish winter and then retreated back to Continental Europe. Two more Jacobite plots, one in 1719 with Spanish support and another in 1722 with the unlikely ambition of taking over London also came to nothing thanks to poor weather in the first case and treachery in the second.

Party Politics

There were two main groups in Parliament: the Whigs and the Tories. The Whigs were a mix of wealthy landowners, business owners, and financial speculators. They were staunch defenders of parliamentary powers and so only wished to see a very limited monarchy. The Tories were more reactionary and largely made up of country gentry who believed in the two great traditions of monarchy and church. Both parties were far from pleased to have a foreign monarch, and so certain additional limitations were imposed on George I, as here summarised by J. Miller: "He was forbidden to leave the three kingdoms without Parliament's permission, or to embark on wars in the interests of a foreign state (Hanover), or to appoint any foreigner to office" (339).

The king was, then, part of a constitutional monarchy where Parliament had important powers, particularly in the domain of taxation. Only Parliament could declare war, and no monarch could dismiss it as had so often happened under the Stuart kings. Although George's English was poor, he was capable in several other languages and so often conducted government in his new kingdom using French and Latin. The king selected his advisers from both parties, although some Tories were suspected of being Jacobite sympathisers, and several were openly so, chief among them the Earl of Mar. Whig newspapers were keen to always describe their opponents as 'Jacobites' rather than 'Tories'. This bias meant that, in the longer term, men seeking power chose to belong to the Whig party and to disassociate themselves from the discredited Tories. The Whigs won the 1715 general election and held on to power for the next 100 years.

Foreign Policy

In 1713-15, the Treaty of Utrecht ended the War of Spanish Succession and resulted in an enlargement of the British colonies in North America (Newfoundland and Nova Scotia) and a lucrative monopoly contract to ship slaves from Africa to colonies of the Spanish Empire. King George was not pleased with the treaty as he had hoped the war would continue against France and so enhance the domains of Hanover. The king never forgave the Tory government for signing the treaty. From 1718 to 1719, Britain was at war with Spain over the latter's expansion in the Mediterranean. A Spanish fleet was destroyed, but another conflict broke out between the two rival powers in 1726 when Spain tried and failed to retake Gibraltar. A peace treaty was signed in 1729, which confirmed Gibraltar as a British possession and permitted British trade with the colonies in Spanish America.

King George was keen to use his new kingdom to further the prosperity of Hanover. One method was to use the powerful Royal Navy to acquire Bremen and Verden, both of which were keenly eyed by Sweden. Their acquisition would give landlocked Hanover crucial access to the North Sea. The strategy – little more than a threat of naval intervention – proved successful, and the two territories were acquired by Hanover in a peace treaty in 1719. A far less successful foreign venture was the king's investment losses in the South Sea Bubble in 1720-21 when a stock company trading on the hypothetical future profits from the slave trade between Africa and the Americas went spectacularly bust.

Fall Out with the Heir

George famously fell out with his son and heir in 1717. The explosion came over the christening of the king's grandson, with a misunderstanding involving the Duke of Newcastle, who, selected to be godfather, thought that Prince George was challenging him to a duel. This unfortunate incident may have been the final act in a long and simmering resentment between the two ever since King George had divorced and so harshly treated the former queen. After the very public row, the king banished his heir from St. James' Palace and even took custody of his grandchildren, permitting only one weekly visit with their parents. Prince George then set up a rival court centred around Leicester House. The prince's court attracted conspirators, discredited Tories, and the out-of-favor Whig politician Robert Walpole, amongst others. Royal relations were restored somewhat in April 1720, but the bond between king and heir was never quite the same again.

Arts & Architecture

King George, as his health waned, took a more distant approach to his rule from 1721, preferring to leave the business of government to his highly capable prime minister Walpole (back in favour thanks to his handling of the fallout of the South Sea Bubble fiasco). George, instead, pursued his other interests such as landscape gardening (for example, at Kensington Gardens), hunting, and science (he supported the first vaccinations against smallpox and became patron of the Royal Society in 1727).

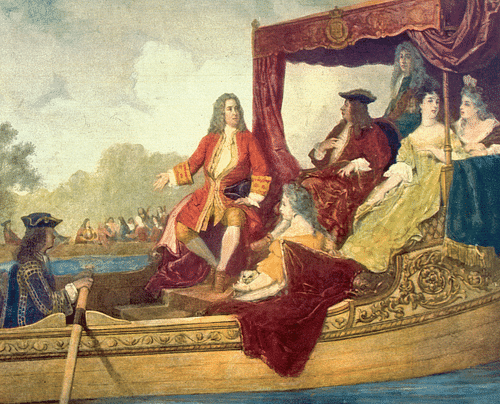

Another great interest was music. The king encouraged the composer George Frideric Handel (1685-1759), commissioning in 1717 the celebrated suite of orchestral movements later collectively called Handel's Water Music. This music was played by an orchestra of 50 musicians as the royal party sailed the River Thames to a picnic and then back again to Whitehall. The king employed Handel to teach music to his granddaughters. George I's support of music was also seen in his large donation to found Handel's Royal Academy of Music.

Architecture was promoted and developed during the reign of George I. So many fine buildings cropped up that the new style became known as 'Georgian'. This style, where symmetry and proportion are emphasised, lasted right through the reigns of George I's three successors. The rather austere style was a sort of reaction against the highly decorative Baroque style seen in Continental Europe, and it eventually developed into the Neoclassical style where elements of the Doric and Ionic orders of ancient Greek and Roman architecture were used with a new toned-down approach to create uniform buildings, squares, and whole avenues of street houses. The royal house in Hanover Square, London is an early example of the style. 50 new churches were built, including St. Anne's Limehouse in London.

The Georgian style (or perhaps more accurately, Georgian styles) in architecture crossed over into the visual arts, notably in clean-looking ceramics (e.g. Wedgwood), curvaceous furniture (e.g. Chippendale), and rich interior design (especially decorative wallpaper). Finally, literature blossomed during George's reign. Famous works published in this period include Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Moll Flanders (1722), as well as Gulliver's Travels (1726) by Jonathan Swift.

The king remained loyal to Hanover and visited six times during his reign, but these extended stays did not endear him to the English aristocracy, which, for the most part, continued to regard him as a rather dull outsider who possessed little passion for governing Britain. "German George" certainly struggled to win over his subjects, but he had at least guided the House of Hanover to a stable and secure start to their long British reign.

Death & Successor

The king suffered poor health in his later years as obesity and gout conspired to give him regular fainting fits. King George died at the age of 67 of a heart attack or stroke on 11 June 1727 at Osnabrück. He was buried in Leineschloss Church in Hanover before being moved to Herrenhausen Palace, the summer residence of the Electors of Hanover. George's only son became his successor as George II. The second George was as dull as his predecessor if a little more popular. He also had to face a Jacobite rebellion, this time in 1745, as the rebels gathered around the Old Pretender's son Charles Edward Stuart, aka 'Bonnie' Prince Charlie (1720-88). This rebellion gathered significant steam thanks to Charles' charisma, but it was, like all those before, ultimately quashed. The Stuart cause died at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. Wider afield, there were several disappointments in foreign wars in America and Europe, but later came successes in Canada and India.

The Hanover Dynasty weathered its dislikable early monarchs who struggled to be taken entirely seriously by their adopted nation. The Hanoverians managed to endure as Britain built its empire thanks to its politicians and armies rather than its sovereigns. The direct British connection with Hanover itself ended when Queen Victoria took the throne in 1837 since a woman was not permitted to rule the German kingdom.