Therapy

Family of Origin Issues in Couples Therapy

Problematic marital interactions usually occur in a wider context

Posted September 12, 2019

THE BASICS

An essay in the Psychotherapy Networker from July/August 2018 by Ellen Wachtel answers a therapist’s question about a difficulty the therapist consistently ran into in his work with married couples. The question was about how to deal with the emotional difficulties of one of the members of the couple without derailing the work on the couples’ relationship issues.

I have a lot of respect for Dr. Wachtel. She, along with her husband Paul, wrote a book called Family Dynamics in Individual Psychotherapy: A Guide to Clinical Strategies, the first edition of which came out in 1986. This was one of the first books that attempted to integrate family systems ideas into individual psychotherapy (it came out when I was still trying to find a publisher for my first book, which attempted to do the same thing).

In my experience, both members of couples who seek marital therapy usually come to their relationship with pre-existing emotional issues – and the problems would come up no matter which member of the couple the therapist focuses on. Dr. Wachtel seems to understand this when she correctly points out that, “It’s common for one person in a couple to believe that the lion’s share of the problems in the relationship arises from the other’s emotional difficulties. As a firm believer that ‘it takes two to tango,’ I try to resist joining with that point of view.”

She goes on to point out that sometimes she nevertheless recommends that the member of the couple with the more dramatic-seeming problem be seen for individual work. He or she invariably reacts with, "Why me? Shouldn’t she (or he) get therapy too?" Or "I react the way I do because he’s so provocative."

Our positions on this subject differ: the major emotional difficulties of each member of the couple in a disturbed relationship are usually part of their relationship problem, and as such cannot really be handled separately. Solving one person’s issues may in some instances actually lead the couple to break up!

I am speaking about major emotional difficulties here – this usually does not apply as much to mild communication problems, one-of-a-kind stressors, or ignorance about such things as managing finances or negotiating compromises.

While one member’s dysfunctional behavior may seem to be far worse than that of the other, in my opinion, both members of the couple have a stake in their relationship continuing in its current dysfunctional form. The way this goes down and the reasons it happens were discussed in my previous posts “I’ll Enable You if You Enable me” and “The Obvious Secret of Interpersonal Influence in Families.”

Briefly, each member of the couple is most usually enabling the other member to maintain a role function that each believes necessary to stabilize their own parents, who are unstable due to an intrapsychic conflict that is shared by their entire family. I call this mutual role function support. Each member of the couple thinks the other member of the couple needs them to play this role because both of them compulsively act out their roles in the face of repeated and obvious drawbacks and negative consequences. Each person would deny this if asked for various reasons, so the other person has to guess why that person continues in their self-defeating or self-destructive habits, and they usually make the guess based on watching their partner interact with the partner’s parents (cross motive reading).

THE BASICS

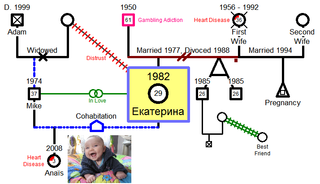

Wachtel comes very close to this formulation by recommending approaching the couple issues by saying, “We’re all stuck with some emotional issues from our childhoods, and even if we work on them in individual therapy, they’re still likely to have a hold on us. In our work together, we’ll try to find ways to keep these issues from affecting the relationship as much as they are now.” She also helps each member of a couple construct their genogram, a graphic representation of a family tree, to “get a window” into the source of problematic patterns.

I would add that the emotional issues are not just from childhood but are in fact family emotional issues that are continuous and ongoing.

Unfortunately, in this piece for the magazine, Wachtel seems to fall into the exact same trap that Murray Bowen — the family systems therapy theorist who first started tracing dysfunctional relationship patterns through genogram construction — fell into. With his patients, as pointed out by Daniel Wile in his book on couples therapy, Bowen used education, logic, and collaboration to help educate his patients on the reasons for their self-destructive behavior.

Therapy Essential Reads

When he sent them back to their families of origin, however, he taught them to use the paradoxical interventions, therapeutic double binds, and maneuvers that are part and parcel of Jay Haley’s alternative type of family systems therapy called strategic family therapy. In a way, he coaches patients to use this type of therapy on their family members instead of employing Bowen therapy. Wile asked why Bowen did not coach his patients on how to use Bowen therapy strategies on their parents.

Wachtel recommends each member of this couple offers support, rather than mere opposition, to the other member’s need to persist in each one's seemingly unproductive habits. In strategic family therapy, this is a paradoxical technique which often seems to have the opposite effect from what it seems to be intended to have: the partner might, in response to being given a green light, start to “be more able to hear his own internal voice that questioned the need to do the task.”

While this can certainly help couples that come from relatively mild dysfunctional families, in my experience with more highly disturbed families, any good that comes from a paradoxical prescription will in fairly short order be undone due to the continued — and far more powerful— influence of the respective families of origin on each member of the couple. The parents and other family members, as I often say, will invalidate the efforts of their adult child to step out of their dysfunctional family role with devastating effectiveness.

I find that members of a couple, with the right coaching, can move from the mutual role function support that attracted them to one another in the first place to becoming allies in the efforts of each to deal with his or her own primary attachment figures. After constructing the two genograms, the therapist can help devise strategies for each member of the couple to stop dysfunctional interactions with each’s own parents. This can be done with the full understanding of the spouse so the spouse knows why their mate is suddenly trying to change things and understands how the devised strategies might actually work. And how and why it might negatively affect the spouse's own relationship with the spouse's parents.

In fact, they can practice the strategies with each other. I go into detail about this process in my recent self-help book. The spouse role plays the role of the other spouse’s targeted parent – and the spouse is usually well acquainted with that in-law and can do so very accurately – while the spouse practices the moves and countermoves planned with the therapist. This practice allows each one to stick with the script more effectively in the face of problematic responses from the parents.