Chapter 24: Frankl: Logotherapy

Part 1: Existential Psychology

Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself. Such is the first principle of Existentialism…For we mean that man first exists, that is, that man first of all is the being who hurls himself toward a future and who is conscious of imagining himself as being in the future…Thus, Existentialism’s first move is to make every man aware of what he is and to make the full responsibility of his existence rest on him. (pg. 456; Jean-Paul Sartre, 1947/1996)

Existential psychology is the area within psychology most closely linked to the field of philosophy. Curiously, this provides one of the most common complaints against existential psychology. Many historians identify the establishment of Wilhelm Wundt’s experimental laboratory in Germany in 1879 as the official date of the founding of psychology. Sigmund Freud, with his strong background in biomedical research, also sought to bring scientific methodology to the study of the mind and mental processes, including psychological disorders and psychotherapy. Shortly thereafter, Americans such as Edward Thorndike and John Watson were establishing behaviorism, and its rigorous methodology, as the most influential field in American psychology. So, as existential psychology arose in the 1940s and 1950s, it was viewed as something of a throwback to an earlier time when psychology was not distinguished from philosophy (Lundin, 1979).

However, as with those who identify themselves as humanistic psychologists, existential psychologists are deeply concerned with individuals and the conditions of each unique human life. The detachment that seems so essential to experimental psychologists is unacceptable to existential psychologists. The difference can easily be seen in the titles of two influential books written by the leading existential psychologists: Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl (1946/1992) and Man’s Search for Himself by Rollo May (1953). Existential psychology differs significantly from humanistic psychology, however, in focusing on present existence and the fear, anguish, and sorrow that are so often associated with the circumstances of our lives (Lundin, 1979).

Understanding the Philosophy of Existentialism

The roots of existentialism as a philosophy began with the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855). Kierkegaard was intensely interested in man’s relationship with God and its ultimate impossibility. Man is finite and individual, whereas God is infinite and absolute, so the two can never truly meet. In pursuing the relationship, however, man goes through three stages or modes of existence: the aesthetic mode, the ethical mode, and the religious mode. The aesthetic mode is concerned with the here and now, and focuses primarily on pleasure and pain. Young children live primarily in this mode. The ethical mode involves making choices and wrestling with the concept of responsibility. An individual in the ethical mode must choose whether or not to live by a code or according to the rules of society. This submission to rules and codes may prove useful in terms of making life simple, but it is a dead end. In order to break out of this dead end, one must live in the religious mode by making a firm commitment to do so. While this may lead to the recognition that each of us is a unique individual, it also brings with it the realization of our total inadequacy relative to God. As a result, we experience loneliness, anxiety, fear, and dread. All of this anguish, however, allows us to know what is really true, and for Kierkegaard, truth was synonymous with faith (in God). However, as important as man’s relationship to God was for Kierkegaard, he was adamantly opposed to organized religion. Kierkegaard rejected objective, so-called “truth” in the form of religious dogma in favor of the subjective “truth” that each person “knows” within themselves. While this subjective, personal truth brings with it the responsibility that leads to anxiety, it can also elevate a person to an authentic existence (Breisach, 1962; Frost, 1942).

Another philosopher considered essential to the foundation of existentialism was the enigmatic German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900). A key element of Nietzsche’s philosophy is the will-to-power. He believed this will-to-power is the fundamental force in the universe (Alfred Adler considered it fundamental to personality development). Ironically, according to Nietzsche, the universe has no regard for humanity. Natural forces (such as disaster and disease) destroy people, life is extremely difficult, and even those who struggle on attempting to realize their will eventually succumb to death. There is no hope to be found in an afterlife, since Nietzsche is famous for declaring that God is dead. Neither is there much hope within society for many people. Nietzsche believed that inequality was the natural state of humanity, so he considered slavery to be perfectly understandable and he felt that women (who are physically weaker than men) should never expect the same rights as men. Nonetheless, Nietzsche saw a great future for humanity, in the belief, indeed the faith, that we would create a superman (or superwoman, as the case may be). It is the creation of the superman that gives purpose to existence. Although the concept of the superman helped to fuel Nazi views on creating a German master race, it also made its way into American comic books as the great hero Superman (Fritzsche, 2007; Frost, 1942; Jaspers, 1965). In perhaps Nietzsche’s most famous work, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, the would-be prophet Zarathustra encouraged people to seek a better future for humanity. “I will teach you about the superman. Man is something that should be overcome. What have you done to overcome him?” (pg. 81, Nietzsche, quoted in Fritzsche, 2007)

The German existentialist Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) and Karl Jaspers (1883-1969) focused on human existence itself and our role in the world. In a sense, Heidegger trivialized the nature of God, equating God with little more than the greatest being in the world, but a being nonetheless (just as humans are). Jaspers was not an atheist, but still his existential theory focused on the human journey toward a freedom that has meaning only when it reveals itself in union with God (Breisach, 1962; Lescoe, 1974). Heidegger considered individuals as beings who are all connected in Being, thus distinguishing between mere beings (including other animals) and the nature of truth or Being. Only humans are capable of understanding this connection between all beings, and Heidegger referred to this discovery as Dasein (“being here,” or existence). On one level, Dasein is common to all creatures, but the possibility of being aware of one’s connection to Being is uniquely human. For those who ask the big questions, Dasein can become authentic existence. This experience comes in the fullness of life, but only if one adopts the mode of existence known as being-in-the-world. Heidegger insisted that Dasein and being-in-the-world are equal. Being-in-the-world is an odd concept, however, since Heidegger believed that Being can only arise from nothingness, and so we ourselves arise as being-thrown-into-this-world. Having been thrown into this mysterious world we wish to make it our own, but our desire for connection with Being leads to anxiety. This anxiety cannot be overcome, because we are aware that we will die. Surprisingly, however, Heidegger considers death to be something positive. It is only because we are going to die that some of us strive to experience life fully. If we can accept that death will come, and nothing will follow, we can be true to ourselves and live an authentic life (Breisach, 1962; Lundin, 1979).

Finally we come to the French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980). Sartre was an extraordinary author and one of the most important philosophers of the twentieth century. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1964, but chose to reject it. More importantly for us, however, is the fact that he carried existential philosophy directly into psychology, with books such as The Transcendence of the Ego (Sartre, 1937/1957) and a section entitled “Existential Psychoanalysis” in his extraordinary work Being and Nothingness (Sartre, 1943). Whereas Kierkegaard believed that man could never truly be one with God, and Heidegger trivialized God, Sartre simply stated that God does not exist. But this is not inconsequential:

The Existentialist, on the contrary, thinks it very distressing that God does not exist, because all possibility of finding values in a heaven of ideas disappears along with Him; there can no longer be an a priori Good, since there is no infinite and perfect consciousness to think it. (pg. 459; Sartre, 1947/1996).

If one looks at the title of Sartre’s most famous philosophical work, Being and Nothingness (Sartre, 1943), you might get the impression that Sartre followed in the footsteps of Heidegger. However, Sartre did not agree with Heidegger (see Sartre, 1943). Sartre divided the world into en-soi (the in-itself) and pour-soi (the for-itself). Pour-soi can be defined as conscious beings, of which there is only one kind: human beings. Everything else is en-soi, things (including non-human animals) that are silent and dead, and from which come no meaning, they only are (Breisach, 1962). For Sartre, there is no mystery, no Being, tying all of creation together. Man’s consciousness is not a connection to God that can be realized, it is simply a unique characteristic of the human species. The nothingness to which Sartre refers is a shell around the pour-soi, the individual, which separates it from the en-soi. People who try to deny living authentically, those who try to deny the responsibility that comes with being conscious and settle into being nothing more than en-soi will have a shattering experience and be totally destroyed (since there is no Being, as described by Heidegger, beyond the shell surrounding the pour-soi; Breisach, 1962). This establishes critical ethical implications for the individual, since their life will be what they make of it, and nothing more.

Unfortunately, many people do reject their unique consciousness and desire to be en-soi, just letting life happen around them. As the en-soi closes in around them, they begin to experience nausea, forlornness, anxiety, and despair. Herein lays the need for existential psychoanalysis:

Existential psychoanalysis is going to reveal to man the real goal of his pursuit, which is being as a synthetic fusion of the in-itself with the for-itself; existential psychoanalysis is going to acquaint man with his passion…Many men, in fact, know that the goal of their pursuit is being; and … they refrain from appropriating things for their own sake and try to realize the symbolic appropriations of their being-in-itself…existential psychoanalysis…must reveal to the moral agent that he is the being by whom values exist. It is then that his freedom will become conscious of itself… (pg. 797; Sartre, 1943)

Sartre proposed that individuals become conscious, and through that consciousness create the world itself, but also that we are “condemned to despair” and “doomed to failure” when we realize that all human activities are merely equivalent. This philosophical approach leads into Sartre’s criticism of the psychology of his time. Sartre believed that psychologists, and even most philosophers, stopped short of really understanding people:

For most philosophers the ego is an “inhabitant” of consciousness…Others – psychologists for the most part – claim to discover its material presence, as the center of desires and acts, in each moment of our psychic life. We should like to show here that the ego is neither formally nor materially in consciousness: it is outside, in the world. It is a being of the world, like the ego of another. (pg. 31; Sartre, 1937/1957)

So, Sartre believed that an existential psychoanalysis was needed to go beyond the limits of Freudian psychoanalysis. It is not enough, according to Sartre, to stop at describing mere patterns of desires and tendencies (Sartre, 1943). In critiquing the psychoanalytic biography of a famous author named Flaubert, Sartre asked very meaningful questions about this individual’s life: Why did Flaubert become a writer instead of a painter? Why did he come to feel exalted and self-important instead of gloomy? Why did his writing emphasize violence, or amorous adventures, etc.? Sartre’s point is a common criticism of Freudian psychoanalytic theory. If most any result can come from an individual’s experiences, then what does psychoanalysis really tell us about anyone? Sartre proposed a deeper form of psychoanalysis.

Placing Existential Psychology in Context: Height Psychology Goes Deeper Than Depth Psychology

The two theorists highlighted in this chapter were truly extraordinary individuals. Both Viktor Frankl (who coined the term “height psychology”) and Rollo May were well immersed in existential thought and its application to psychology when they faced seemingly certain death. For Frankl, who was imprisoned in the Nazi concentration camps, death was expected. For May, who was confined to a sanitarium with tuberculosis, death was a very real possibility (and indeed many died there). But Frankl and May were intelligent, observant, and thoughtful men. They watched as many died, while some lived, and they sought answers that might explain who was destined for each group. Both men observed that for those who resigned themselves to death, death came soon. But for those who chose to live, they had a real chance to survive despite the terrible conditions in which they existed.

Frankl and May also shared their training in traditional psychoanalysis, and both had studied with Alfred Adler, at least in part. However, they found the so-called depth psychology as lacking, since it did not address the true potential for humans to rise above their conditions. In this regard, existential psychologists have typically been viewed as belonging within the humanistic psychology camp. However, both Frankl and May considered humanistic psychology to also be lacking in that it neglected the true potential for humans to make bad choices and to harm both themselves and others. So for existential psychologists, the center of their focus is on the immediate existence of the individual and in the context of their relationship to others. It is this seeming paradox, and the drive to resolve it, that provides the motivation and energy for life.

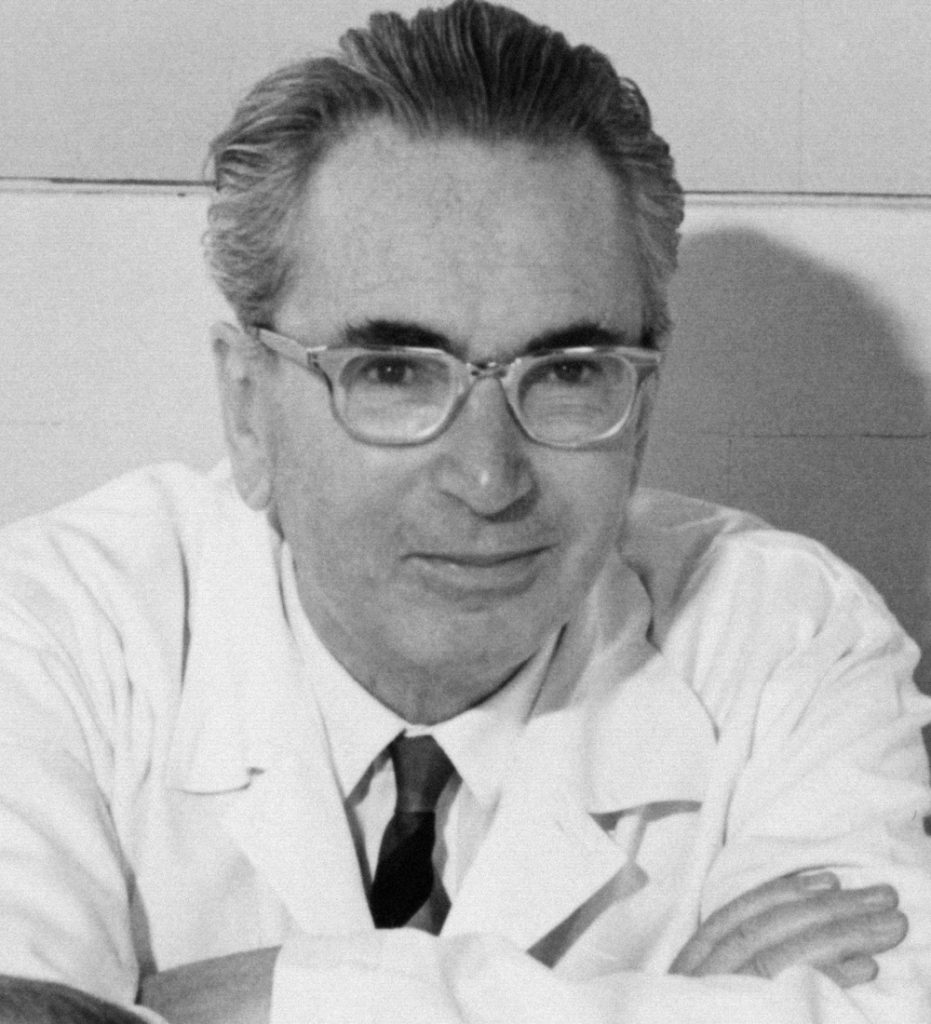

A Brief Biography of Viktor Frankl

Viktor Frankl (1905-1997) was truly an extraordinary man. His first paper was submitted for publication by Sigmund Freud; his second paper was published at the urging of Alfred Adler. Gordon Allport was instrumental in getting Frankl’s book, Man’s Search for Meaning (Frankl, 1946/1992), published in English, a book that went on to be recognized by the Library of Congress as one of the ten most influential books in America. He lectured around the world, and received some thirty honorary doctoral degrees in addition to the medical degree and the Ph.D. he had earned as a student. He was invited to a private audience with Pope Paul VI, even though Frankl was Jewish. All of this was accomplished in spite of, and partly because of, the fact that he spent several years in Nazi concentration camps during World War II, camps where his parents, brother, wife, and millions of other Jews died.

Viktor Frankl was born in Vienna, Austria on March 26, 1905. Although his father had been forced to drop out of medical school for financial reasons, Gabriel Frankl held a series of positions with the Austrian government, working primarily with the department of child protection and youth welfare. He instilled in his son the importance of being intensely rational and having a firm sense of social justice, and Frankl became something of a perfectionist. Frankl described his mother Elsa as a kindhearted and deeply pious woman, but during his childhood, she often described him as a pest, and she even changed the words of Frankl’s favorite childhood lullaby to include calling him a pest. This may have been due to the fact that Frankl was often asking questions, so much so that a family friend nicknamed him “The Thinker” (Frankl, 1995/2000). From his mother, Frankl inherited a deep emotionality. One aspect of this emotionality involved a deep attachment to his childhood home, and he often felt homesick as his responsibilities kept him away, and those responsibilities began at an early age (Frankl, 1995/2000; Pattakos, 2004).

Even in high school, Frankl was developing a keen interest in existential philosophy and psychology. At the age of 16 he delivered a public lecture “On the Meaning of Life,” and at 18 he wrote his graduation essay “On the Psychology of Philosophical Thought.” Throughout his high school years he maintained a correspondence with Sigmund Freud (letters that were later destroyed by the Gestapo when Frankl was deported to his first concentration camp). When Frankl was just 19, Freud submitted one of Frankl’s papers for publication in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis, afterward hoping that Frankl would agree and give his belated consent. Despite having impressed Freud, Frankl himself was already impressed by Alfred Adler. Frankl became active in Adler’s individual psychology group, and as he began medical school, he was urged by Adler to publish a paper in the International Journal of Individual Psychology. It is hard to imagine that many people could have come into the favor of both Freud and Adler by such a young age, even before having begun medical school or a career in psychiatry. Despite Frankl’s young age and somewhat limited experience, the paper published by Adler was dealing with difficult material, specifically the “border area that lies between psychotherapy and philosophy, with special attention to the problems of meanings and values in psychology” (Frankl, 1995/2000). Eventually, however, Frankl fell out of favor with Adler. Frankl had been impressed with two men, Allers and Schwarz, whose views were at odds with Adler. On the evening when Allers and Schwarz announced to the society that they could not agree with Adler, Adler challenged Frankl and a friend to speak up. Frankl chose to do so, and he defended Allers and Schwarz, believing that a middle ground could be found. Adler never spoke to Frankl again, even when Frankl said hello in the local coffee shop. For a few months, Adler had other people suggest to Frankl that he should quit the society. When Frankl did not, he was expelled by Adler (Frankl, 1995/2000; Pattakos, 2004).

Frankl proceeded to develop his own practice and his own school of psychotherapy, known as logotherapy (the therapy of meaning, as in finding meaning in one’s life). As early as 1929, Frankl had begun to recognize three possible ways to find meaning in life: a deed we do or a work we create; a meaningful human encounter, particularly one involving love; and choosing one’s attitude in the face of unavoidable suffering. Logotherapy eventually became known as the third school of Viennese psychotherapy, after Freud’s psychoanalysis and Adler’s individual psychology. During the 1930s, Frankl did much of his work with suicidal patients and teenagers. He had extensive talks with Wilhelm Reich in Berlin, who was also involved in youth counseling by that time. As the 1930s came to an end, and Austria had been taken over by the Nazis, Frankl sought a visa to emigrate to the United States, which was eventually granted. However, Frankl’s parents could not get a visa, so he chose to remain in Austria with them. He also began work on his first book, eventually published in English under the title, The Doctor and the Soul (Frankl, 1946/1986), which provided the foundation for logotherapy. He fell in love with Tilly Grosser, and they were married in 1941, the last legal Jewish marriage in Vienna under the Nazis.

Shortly thereafter, the realities of Nazi Germany overcame what little privilege Frankl had enjoyed as a doctor at a major hospital. Since it was illegal for Jews to have children, Tilly Frankl was forced to abort their first child. Frankl later dedicated The Unheard Cry for Meaning “To Harry or Marion an unborn child” (Frankl, 1978). Then the entire Frankl family, except for his sister who had gone to Australia, was deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp (the same camp from which Anna Freud cared for orphans after the war). As they marched into the camp with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of other prisoners, his father tried to calm those who panicked by saying again and again: “Be of good cheer, for God is near.” Frankl’s parents, his only brother, and his wife Tilly died in the concentration camps. Most tragically, Frankl believed that his wife died after the war, but before the liberating Allied forces could care for all of the many, many suffering people (Frankl, 1995/2000).

When Frankl was deported, he tried to hide and save his only copy of The Doctor and the Soul by sewing it into the lining of his coat. However, he was forced to trade his good coat for an old one, and the manuscript was lost. While imprisoned, he managed to obtain a few scraps of paper on which to make notes. Those notes later helped him to recreate his book, and that goal gave such meaning to his life that he considered it an important factor in his will to survive the horrors of the concentration camps. It would be difficult to adequately describe the conditions of the concentration camps, or how they affected the minds of those imprisoned, especially since the effects were quite varied. Frankl describes those conditions in Man’s Search for Meaning. The book is rather short, but its contents are deep beyond comprehension. Frankl himself, however, might take exception to referring to his book as “deep.” Depth psychology was a term used for psychodynamically-oriented psychology. In 1938, Frankl coined the term “height psychology” in order to supplement, but not replace, depth psychology (Frankl, 1978).

After the war, Frankl’s life was nothing less than amazing. He returned to his home city of Vienna, married Eleonore Katharina, née Schwindt, and raised a daughter named Gabriele. He lectured around the world, received many honors, wrote numerous books, all while continuing to practice psychiatry and teach at the University of Vienna, Harvard, and elsewhere. He had a great interest in humor and in cartooning. Throughout his life, Frankl steadfastly refused to acknowledge the validity of collective guilt toward the German people. When asked repeatedly how he could return to Vienna, after all that happened to him and his family, Frankl replied:

…I answered with a counter-question: “Who did what to me?” There had been a Catholic baroness who risked her life by hiding my cousin for years in her apartment. There had been a Socialist attorney (Bruno Pitterman, later vice chancellor of Austria), who knew me only casually and for whom I had never done anything; and it was he who smuggled some food to me whenever he could. For what reason, then, should I turn my back on Vienna? (pp. 101-102; Frankl, 1995/2000)

Viktor Frankl died peacefully on September 2, 1997. He was 92 years old. During his life, his work influenced many people, from the ordinary to the famous and influential.

Supplemental Materials

Viktor Frankl Biography: A Search for Meaning

This video [16:03] provides a comprehensive biography of the life of Viktor Frankl.

Source: https://youtu.be/JlQRny6bUlE

Existentialism: Crash Course Philosophy #16

This video [8:53] explores essentialism and its response: existentialism. The video discusses Jean-Paul Sartre and his ideas about how to find meaning in a meaningless world.

Source: https://youtu.be/YaDvRdLMkHs

This video [4:53] provides a brief overview of existential psychology and how knowledge of our own mortality may play a role in shaping behaviors and societies.

Source: https://youtu.be/wrWsUaFo-Xo

References

Text: Kelland, M. (2017). Personality Theory. OER Commons. Retrieved October 28, 2019, from https://www.oercommons.org/authoring/22859-personality-theory. Licensed under CC-BY-4.0.

Biographics. (2017, December 15). Viktor Frankl biography: A search for meaning. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/JlQRny6bUlE. Standard YouTube License.

CrashCourse. (2016, June 6). Existentialism: Crash course philosophy #16. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/YaDvRdLMkHs. Standard YouTube License.

PsychExamReview. (2017, September 28). Existential psychology (Intro psych tutorial #143). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/wrWsUaFo-Xo. Standard YouTube License.