Did Emperor Constantine Choose the Books of the Bible at the Council of Nicaea?

How a bizarre medieval tale about a miracle on a communion table evolved into a cultural myth and made its way into the modern mind

I rarely read reviews of anything I write, but I made an exception when a colleague sent me a link to an online review of one of my books. Someone was apparently disappointed with a history of the Bible that I had produced. The reviewer slapped the book with a two-star rating on a five-star scale and entitled her review “Not Much Historical Information.”

What caught my attention in the review wasn’t the fact that this individual disliked what I wrote. A lot of people can’t stand certain books that I’ve written, including my own children and nearly everyone in the churches in which I grew up. Some days, when I’m reviewing what I’ve written, I completely agree with their assessments. What interested me was what this reviewer thought I’d failed to cover between the covers of this particular book.

How Can You Talk about the Invention of the Electric Light Bulb and Never Mention Elvis Presley?

“My Bible study class wanted to learn more about how the Bible came to be compiled,” she wrote. “We ordered this in hopes to gain more information on the Council of Nicaea — which books were and were not chosen and why.” At this point, the reviewer — who was, I’m certain, well-intended and sincere in her disappointment — launched into a critique of the book’s failure to describe in detail how the leaders of the Church chose the books of the Bible at the Council of Nicaea. At the culmination of her review, she declared in apparent despair, “One of my Bible study members remarked, ‘How can he talk about how the Bible came to be and not mention the Council of Nicaea?’ My point exactly.”

The Council of Nicaea was a gathering of church leaders that took place in the year 325 A.D., about eighty miles south of the metropolis known today as Istanbul, Turkey. If this council had made any decisions whatsoever about which texts ended up in the Bible, the reviewer’s concerns would have made perfect sense. The problem is, however, that the Council of Nicaea had nothing to do with any aspect of how the Bible was brought together.

Asking “How can he talk about how the Bible came to be and not mention the Council of Nicaea?” is like asking, “How can you talk about the invention of the electric light bulb and not mention Elvis Presley?” The Council of Nicaea had every bit as much to do with the formation of the Bible as Elvis had to do with the creation of the electric light bulb. Elvis may have benefited from the light bulb, but he had nothing to do with its invention.

The church leaders who made the journey to Nicaea in the fourth century traveled there to discuss what the first-century apostles had taught about the nature of Jesus. Over the space of three months, the council composed a creed and discussed at least twenty issues, including whether pastors could be married and whether or not the apostles had thought Jesus was fully divine (their answer was “yes” to both of these questions). And yet, as far as anyone can tell from the historical evidence, nothing related to the books of the Bible was discussed, decided, or declared at the Council of Nicaea.

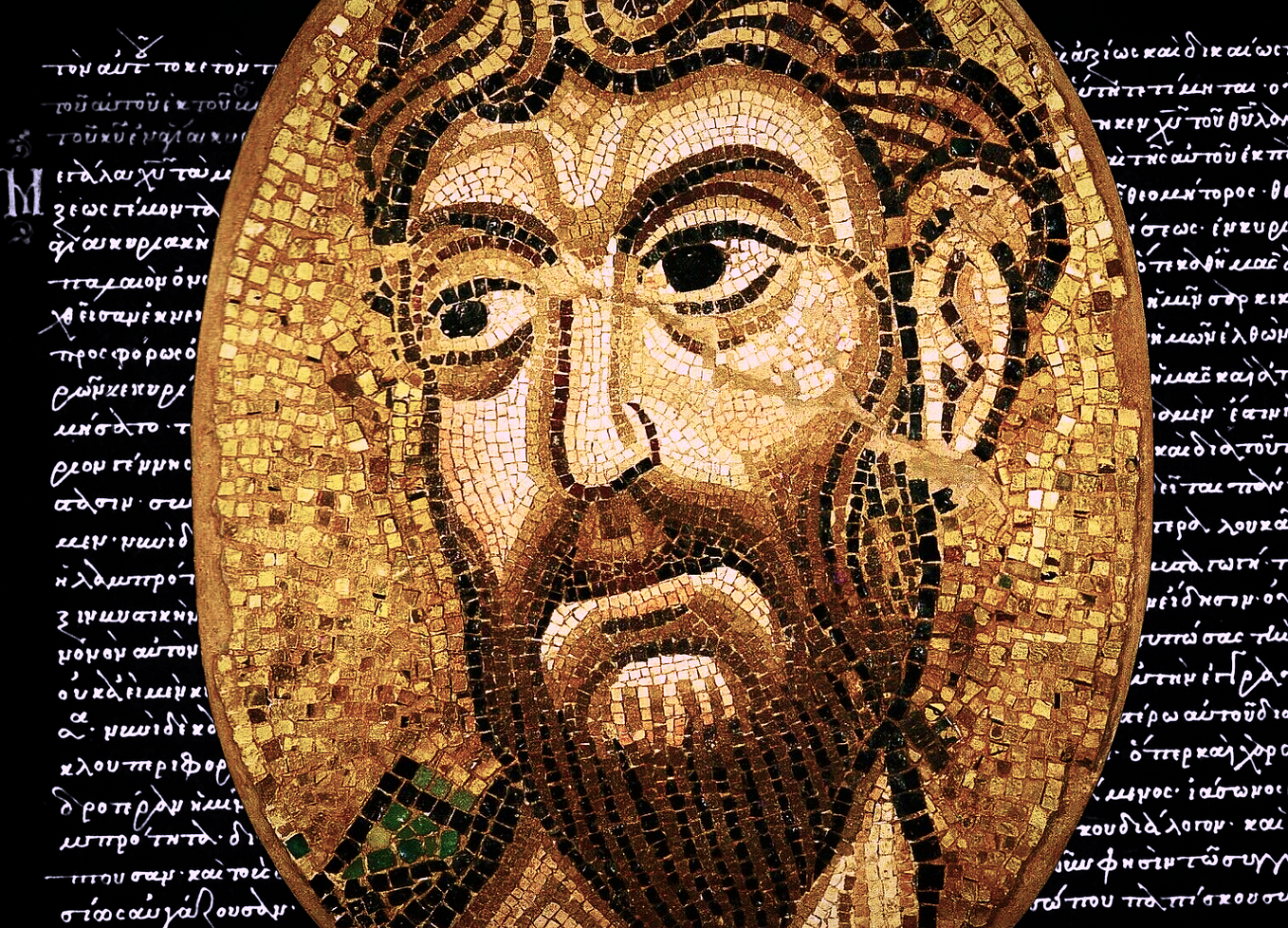

How a Medieval Myth Made Its Way into the Modern Mind

Why, then, are so many people convinced that the Council of Nicaea had something to do with which books ended up in the Bible?

It seems that this mistruth may be traceable to a myth that emerged in the Middle Ages.

According to an anonymous document from the ninth century A.D., church leaders at the Council of Nicaea piled all the books that were candidates for inclusion in the Bible on a communion table and prayed. As they prayed, all the spurious texts slipped through the table and crashed to the floor. The Bible was formed from the books that stayed on top of the table. If this really happened, it would greatly simplify the question of how certain books ended up in the Bible. (Also, if such a trial by ordeal really worked, I would be tempted to try it whenever two or more of my children give me contradictory reports about who did what. Each time my children’s stories conflicted with one another, I would simply seat the four of them in a row on the coffee table, pray until the less-truthful children hit the floor, and then give cookies to everyone who stayed on top of the table.)

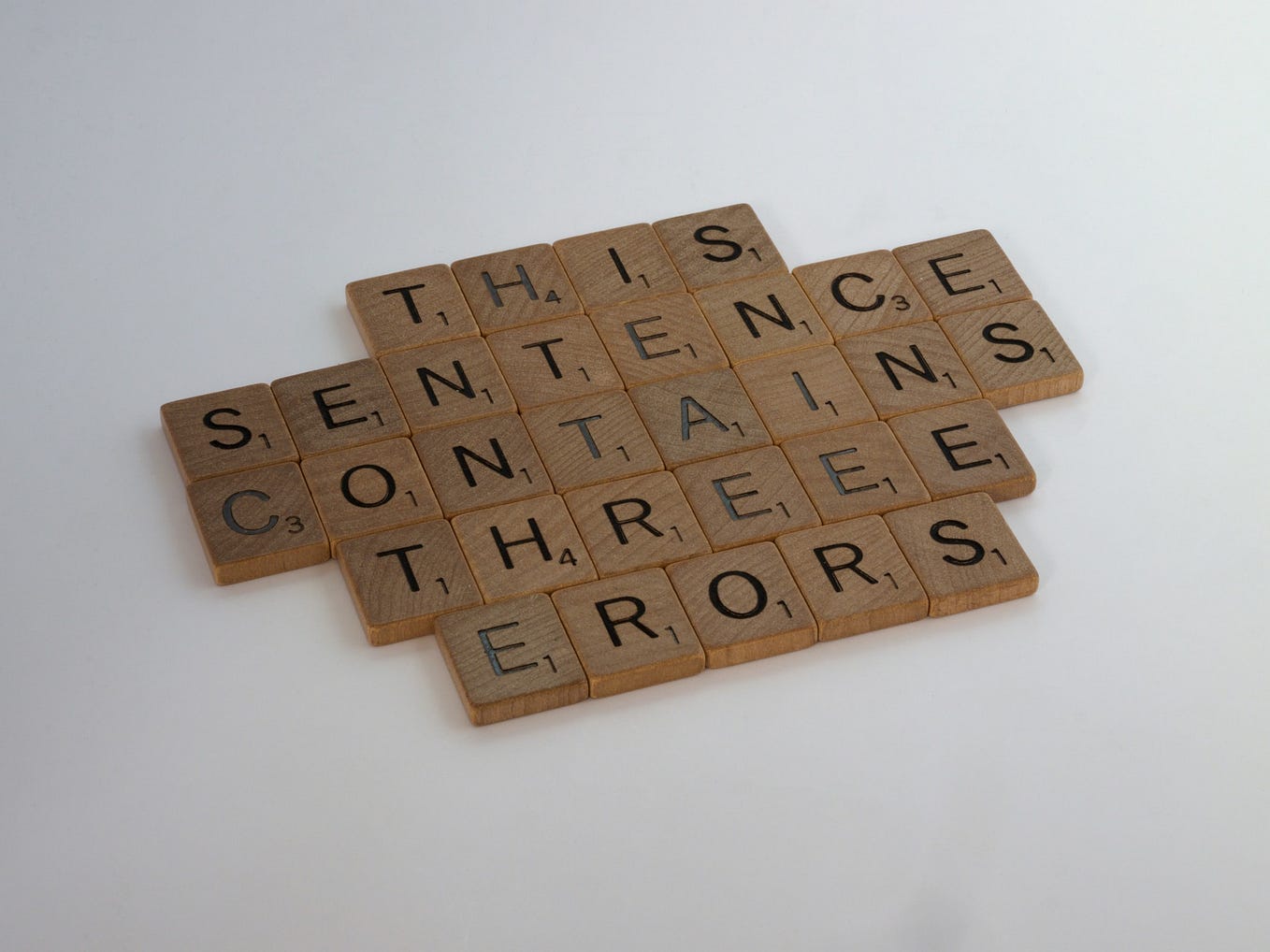

Unfortunately for the question of which texts belong in the Bible (as well as for my capacity to discern which ones of my children are telling the truth), there is no reliable evidence that any such event ever took place at Nicaea or anywhere else. This seems like the sort of bizarre occurrence that people would talk about after the council was over, yet no one who attended the Council of Nicaea ever mentioned any event of this sort. The earliest description of these alleged discussions shows up in a single document copied more than six centuries after the final session of the council. As such, no modern scholar has ever taken seriously this account of the formation of the Bible. Simply put, the table of contents in your Bible was not formed from the content that stayed on top of the table at the Council of Nicaea.

An eighteenth-century philosopher named Voltaire popularized the myth of this literary ordeal when he satirized it in his philosophical dictionary. From that point forward, links between the Council of Nicaea and which books ended up in the Bible have continued to pop up in popular descriptions of the formation of the Bible.

In 2005, Dan Brown connected the Council of Nicaea to the creation of the Bible in his bestselling novel The Da Vinci Code, but Brown also added a twist that he had picked up from some twentieth-century conspiracy theories. According to The Da Vinci Code, it was not the leaders of the Church but Constantine the emperor who collated and edited the books of the Bible at the Council of Nicaea. And so, a medieval myth wormed its way into the modern imagination through a satirical philosopher, a handful of conspiracy theorists, and a bestselling novelist.