The Life of Elisabeth of Austria, Queen Consort of France

As daughter of Emperor Maximilian II and Maria of Spain, she was a born royal. As wife of Charles IX of France, her life was steeped with tragedy and turmoil.

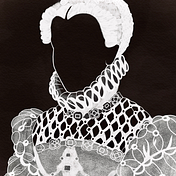

As perhaps the most attractive member of the Habsburg dynasties of Spain and Austria that ever lived, Elisabeth of Austria was born in 1554, the second daughter to Maria and Maximilian, the Imperial couple of the Holy Roman Empire. In true fashion of the Habsburg family tree looking more like an imperial wreath, Elisabeth’s parents were first cousins. Her mother was the daughter of Emperor Charles V, and her father Maximilian II the son of that Emperor’s brother Emperor Ferdinand I.

As perhaps the most attractive member of the Habsburg dynasties of Spain and Austria that ever lived, Elisabeth of Austria was born in 1554, the second daughter to Maria and Maximilian, the Imperial couple of the Holy Roman Empire. In true fashion of the Habsburg family tree looking more like an imperial wreath, Elisabeth’s parents were first cousins. Her mother was the daughter of Emperor Charles V, and her father Maximilian II the son of that Emperor’s brother Emperor Ferdinand I.

Yet Elisabeth, as well as her elder sister Anna, looked rather more like pretty women with the faintest resemblance to the characteristic Habsburg traits of a strong jaw and enlarged lips — particularly the bottom lip. This is most likely due to the fact that both princesses took after their father, who in turn took after his own mother, Anna of Bohemia and Hungary. This grandmother Anna wasn’t a member of the Habsburg dynasty, and therefore she injected some much-needed ‘clean blood’ into the family line.

Childhood

Both princesses were marked out for greatness, being members of the powerful imperial dynasty that would supply Holy Roman Emperors (of lands roughly equivalent to present-day Germany) until at last the inbreeding faded away with the death of the Spanish Habsburg branch of the family. And Anna, elder sister that she was, was immediately chosen for the second time a member of the Austrian branch married the Spanish branch. Anna and Elisabeth’s mother Maria had been the first, and thus it was decided that Anna would marry King Philip II of Spain’s son Don Carlos.

Don Carlos, however, died before this came to pass, though before this happened Philip II had intentionally delayed nuptials because he began to recognise his son was too unstable for wedlock. After Don Carlos’s death, Philip II decided that he would offer himself up to the task, considering he was now also without a male heir. Anna, who had been born in Spain during her parents’ regency period there, returned to her country of origin. Elisabeth, who was almost five years younger than her sister, still had a few more years to wait before her own wedding.

By all accounts, Maximilian II doted on his daughters. It was said that when his eldest child Anna was sick, he postponed a meeting of the Estates of Hungary. Elisabeth resembled him even more closely than her sister, having inherited her father’s looks and his character. She was as intelligent as he was, and even let curiosity get the better of her and joined her brothers in some of their special education. She was, as were her siblings, also brought up as a faithful Catholic, showing great piousness and caring for the poor and innocent throughout her life.

She was fluent in German, Spanish, Latin, and Italian, though she had some trouble learning French. It is, therefore, no wonder that she felt a little lonely at the French court, though her sister-in-law Marguerite was a notable exception to this. The two princesses took to one another almost immediately, and the bond between them would only strengthen over the years and last until Elisabeth’s early death.

Marriage to King Charles IX

When she became queen of France as Charles IX’s consort, she raised eyebrows at the fact that people did not take their Catholicism as seriously as she had been taught to do. It was said that she attended Mass twice a day, whereas some courtiers in France only did so a few times a week — or, as can be guessed from other contemporary behaviours, only attending Mass duly on Sundays. She had evidently not inherited her father’s tolerance for other ways of worship within Christianity, being rather more in that regard a reflection of her maternal grandfather Emperor Charles V.

She was young when she was betrothed to Charles IX of France, who had succeeded his elder brother Francis II at a young age. The ambassador that saw her was delighted with the way she appeared before him and was said to have exclaimed that this was indeed the queen of France. Yet, it would be several more years until Elisabeth was married off to the young king. When at last this occurred, Elisabeth first met her sister-in-law Marguerite of Valois, as well as her brother-in-law (and future king of France) Henri (III). While they tended to her, Charles IX had dressed up as an ordinary citizen and stood among the crowd, watching his new bride.

He was immediately enthusiastic about the match, undoubtedly due to Elisabeth’s attractive appearance and her agreeable personality. Though as was the case with several of her son’s wives, Queen Mother Catherine de Medici was less impressed with the young Austrian princess. Noteworthy also is the fact that Charles IX’s mistress, whom he kept even after his marriage and who later bore him a son, said of Elisabeth, ‘The German girl doesn’t scare me.’ Yet Charles IX and Catherine both recognised that Elisabeth’s innocence and naivety would render it wise to shelter her from the flamboyance and loose morals of the French court, and so Elisabeth never had a full taste of just how bad it was to her sensibilities.

An interesting detail, considering the period in which Elisabeth lived, is that she was so taken with her husband that she wasn’t afraid to kiss him in public, to the amusement of many ladies at the French court. Although, it is noteworthy to point out that Elisabeth was likely a lot more chaste than many of those who made fun of her for her behaviour. For Elisabeth, her marriage was certainly a love match, though Charles’s eyes would continue to wander throughout their union. He was, however, devoted to her in the sense that he liked her and sought to make her feel as comfortable as possible.

There was but one controversy that Elisabeth was involved in during her time as queen of France. Due to her deep sense of Catholicism, she refused the Huguenot (Protestant) leader Gaspard II de Coligny, the Admiral of France, permission to kiss her hand as he came to pay his respects to the royal family. De Coligny was a close friend and adviser to Elisabeth’s husband Charles IX, and he was reportedly devastated at the admiral’s death during the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572. Even Elisabeth, while personally opposed to the way in which the Huguenots went about their religion, was distraught at the event. At the time of its occurrence, she was pregnant with her only child, Marie Elisabeth.

Widowhood

Charles IX suffered from general poor health throughout his life, possibly stemming from genetic syphilis inherited from his maternal grandfather Lorenzo II de Medici. A little while before the birth of his only legitimate child, Marie Elisabeth of Valois, in 1572, his condition worsened. Possibly aggravated by the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre a few months before Marie Elisabeth’s birth, Charles became increasingly ill and mentally unstable.

He would exclaim his regret over what had happened, ask God to forgive him for his role in the events that saw thousands of French Protestants (Huguenots) murdered in the streets, and on one occasion even berated his own mother. According to him, Catherine de’ Medici was to blame, even going as far as to call her ‘the cause of it all’. Catherine, ever the stern and vigorous (bordering on cruel at times) Queen Mother of France, said her son was a lunatic.

It is noteworthy that of Catherine de Medici’s five sons, four lived to a reasonable age. Three of those four would become kings of France, and in some sort of cruel twist of fate, those exact three would be the ones suffering mental instabilities. Henri III, the younger brother of Charles IX who succeeded him as king of France, had good health overall, even inviting jealousy from Charles as a result of his excellent physique and energy. Yet, for all the contempt with which Charles could regard Henri, when Henri became king he was as appalled as Elisabeth of Austria was at the suggestion that they should marry one another.

When Charles IX neared his end, his bouts of madness increased severely. Throughout his ordeal, Elisabeth stayed loyally at her husband’s side, sharing his suffering until, at last, his body gave way. It was said that the queen wept tears ‘so tender and so secret’ at his bedside as he passed. She had loved Charles more than he had loved her, though his care for her well being has to be noted. Both had been a tad disappointed at the birth of their daughter, but they had also delighted in that a child was born to them in the first place. Marie Elisabeth would, throughout her short five years on this earth, learn her Valois (French) and Habsburg (Austrian) heritage off the top of her head, and would proudly tell everyone that she belonged to both great houses.

She also was purportedly a delight to others at court, being a well-behaved and sweetly child who carried herself with dignity befitting a princess of France. When she died at such a tender age as she did, the whole court mourned her deeply. She had been Catherine de Medici’s first and only Valois grandchild — Marie Elisabeth’s death would, in light of her great-grandmother Claude of France who had married her great-grandfather King Francis I, seriously implement succession. Despite the fact that women could not become queens of France in their own right, her great-grandmother Claude had been the daughter of the previous king (Louis XII) while her marriage to that king’s relative Francis I ensured the succession stayed indisputable.

Henri III and his sister-in-law had a good relationship, and Henri would take it upon himself to provide good care for his brother’s legitimate daughter Marie Elisabeth, as well as provide for his illegitimate son by a mistress and his widow Elisabeth of Austria. When Elisabeth’s father, Emperor Maximilian II, asked her to return to Austria, she duly obliged him as well. While she was away, her daughter Marie Elisabeth died. She’d last seen her mother when she was almost three years old. Some time before the death of her daughter, Elisabeth of Austria had also lost her beloved father Maximilian II.

With her brother Rudolf II becoming the next Holy Roman Emperor, Elisabeth was asked by her uncle (her mother Maria’s brother) to marry him after her elder sister (her uncle’s fourth wife) had passed away. To this, Elisabeth was reported to have said, ‘The queens of France do not remarry’. It was a famous phrase said by queen consort Blanche of Navarre, and it settled the matter on her part. Elisabeth would remain Charles IX’s widow for the rest of her life, and Philip II of Spain was left to try his last bit of luck with Elisabeth’s youngest sister, who also rejected his offer. (Or rather second youngest, the actual youngest had died aged eleven in the same year as Anna.) Thus, her elder sister Anna was Philip II’s last wife, and the mother of the son that would succeed him after death.

Elisabeth never lived to see that come to pass. She lived her final years dressed in mourning, and when her former sister-in-law Marguerite was ostracised from the royal family, Elisabeth maintained correspondence with her and made half of her French funds due to her as a king’s widow available to Marguerite. She also founded a convent in Austria, as well as restoring a chapel in Prague, and she devoted the remainder of her life to piety, health care, and relief of the poor. She also provided a gentle haven of support for impoverished noblewomen. While still in France, she had founded a Jesuit college in Bourges as well.

In 1592, Elisabeth became a victim of pleurisy, dying in January. In her will, she donated money for the poor and the sick but made sure to also make funds available for prayers to be said for her late husband Charles IX. The works of literature and religious books she owned went to her brother Emperor Rudolf II, and her wedding ring went to her brother Archduke Ernest. While still alive, she had sent her sister-in-law Marguerite two works written by herself, though unfortunately they are now lost to time. When she died, her mother Maria was reported to have said, ‘The best of us is dead.’ Elisabeth was only thirty-seven when she passed away.

Elisabeth was originally buried under a simple and modest marble slab in the church of the convent she’d founded, though during the 18th century her monastery was closed and the then-emperor Joseph II, brother of the famous Marie Antoinette who was like Elisabeth a queen consort of France, had her remains transferred to a crypt beneath St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. Vienna, incidentally, was the city of Elisabeth’s birth, and the cathedral she lies buried beneath was the site of the wedding of her grandfather Ferdinand I and Anna of Bohemia and Hungary. In the same year as Elisabeth’s reburial, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart married his wife there too.