Alexandra Feodorovna (Charlotte of Prussia)

| Alexandra Feodorovna | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Franz Krüger, c. 1836 | |||||

| Empress consort of Russia | |||||

| Tenure | 1 December 1825 – 2 March 1855 | ||||

| Coronation | 3 September 1826 | ||||

| Born | Princess Charlotte of Prussia 13 July 1798 Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia, Holy Roman Empire | ||||

| Died | 1 November 1860 (aged 62) Alexander Palace, Tsarskoye Selo, Russian Empire | ||||

| Burial | Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

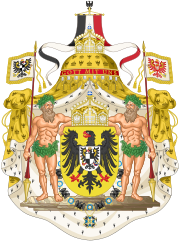

| House | Hohenzollern | ||||

| Father | Frederick William III of Prussia | ||||

| Mother | Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz | ||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodox previously Calvinism | ||||

| Prussian Royalty |

| House of Hohenzollern |

|---|

|

| Frederick William III |

|

Alexandra Feodorovna (Russian: Алекса́ндра Фёдоровна, IPA: [ɐlʲɪˈksandrə ˈfjɵdərəvnə]), born Princess Charlotte of Prussia (13 July 1798 – 1 November 1860), was Empress of Russia as the wife of Emperor Nicholas I (r. 1825–1855).

Princess of Prussia[edit]

Empress Alexandra Feodorovna was born as Princess Friederike Luise Charlotte Wilhelmine of Prussia, at the Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin on 13 July [O.S. 1 July] 1798.[1] She was the eldest surviving daughter and fourth child of Frederick William III, King of Prussia, and Duchess Louise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, and a sister of Frederick William IV and of William I, German Emperor. She was known as Charlotte, a name popular in the Prussian royal family,[1] and nicknamed Lottchen by her family.[2]

The princess's childhood was marked by the Napoleonic Wars and she was raised under difficult financial conditions.[3] Her father was a kind, religious man but a weak and indecisive ruler who, following military defeats in 1806, lost half of his kingdom. Charlotte's mother, admired for her beauty, intellect, and charm, was considered more decisive than her husband.[1] When the Prussians were defeated at the battle of Jena, Louise fled to Königsberg, taking her children with her, Charlotte then being eight years old. In East Prussia, they were given protection by Tsar Alexander I. "My daughter Charlotte is reserved and concentrated, but like her father, her seemingly cold appearance conceals the beating of her hot compassionate heart", wrote Queen Louise about her daughter.[4] On 27 October 1806, Berlin fell under Napoleon's control and Charlotte grew up in war-torn Memel, Prussia. In December 1809, Queen Louise finally returned to Berlin with her children, but after a few months, became ill and died of typhus at the age of 34, shortly after Charlotte's twelfth birthday.[3] As the eldest daughter, Charlotte was now the most senior lady at the court and had to undertake her mother's duties.[citation needed] For the rest of her life, Charlotte treasured her mother's memory.[5]

Marriage[edit]

In February 1814, Grand Duke Nicholas Pavlovich, future Tsar of Russia, and his brother Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich, visited Berlin.[4][6] Arrangements were made between the two dynasties for Nicholas to marry Charlotte, then fifteen years old, to strengthen the alliance between Russia and Prussia.[7]

Nicholas was only second in line to the throne, as the heir was his brother Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich who, like Tsar Alexander I, was childless. On a second visit the following year, Nicholas fell in love with the then-seventeen-year-old Princess Charlotte. Nicholas was tall and handsome with classical features.[6] The feeling was mutual, "I like him and am sure of being happy with him". She wrote to her brother, "What we have in common is our inner life; let the world do as it pleases, in our hearts we have a world of our own". Hand-in-hand, they wandered over the Potsdam countryside, and attended the Berlin Court Opera. By the end of his visit, in October 1816, Nicholas and Charlotte were engaged.[8] They were third cousins as great-great-grandchildren of Frederick William I of Prussia.

On 9 June 1817 (O.S.) Princess Charlotte came to Russia with her brother William.[9] After arriving in St. Petersburg she converted to Russian Orthodoxy, and took the Russian name "Alexandra Feodorovna".[10] On her nineteenth birthday, 13 July [O.S. 1 July] 1817, she and Nicholas were married in the Grand Church of the Winter Palace.[8] "I felt myself very, very happy when our hands joined", she would later write about her wedding. "With complete confidence and trust, I gave my life into the hands of my Nicholas, and he never once betrayed it".[11]

Grand Duchess[edit]

At first, Alexandra Feodorovna had problems adapting to the Russian court, the change of religion affected her and she was overwhelmed by her new surroundings. She gained the favor of her mother-in-law, Maria Feodorovna, but did not get along well with the Empress Elizabeth Alexeievna, consort of her brother-in-law. "I was very weak, very pale and (they claimed) very interesting-looking", she recalled later.[12]

Pregnant with her first child, Alexandra traveled to Moscow where, on 29 April [O.S. 17 April] 1818, she gave birth to her first son, the future Tsar Alexander II.[12] The next year, 18 August [O.S. 6 August] 1819 in Krasnoye Selo, she had a daughter, Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna. That summer, Tsar Alexander I announced privately to Nicholas and Alexandra his intention of eventually abdicating during his lifetime and that Nicholas would succeed him since their brother Constantine intended to marry morganatically.[13] In 1820 Alexandra delivered a stillborn daughter, which brought on a deep depression. Her doctors advised a holiday, and in the autumn of 1820 Nicholas took her to see her family in Berlin, where they remained until the summer of 1821, returning again in the summer of 1824. They did not come back to St. Petersburg until March 1825 when Tsar Alexander I required their presence in Russia.

Alexandra Feodorovna spent her first years in Russia trying to learn the language and customs of her adopted country under the tutelage of the poet Vasily Zhukovsky, whom she characterized as being "too much of a poet to be a good tutor". The Imperial family spoke German and wrote their letters in French, which was widely spoken at the Russian court, and as a consequence, Alexandra never completely mastered the Russian language.[14]

Alexandra Feodorovna wrote in her memoirs of her first years in Russia, "We both were truly happy only when we found ourselves alone in our apartments, with me sitting on his knees while he was loving and tender". Nicholas nicknamed his wife "Mouffy".[15] For eight years, during the reign of Tsar Alexander I, the couple lived quietly. Tsar Alexander I had no surviving children and his heir, Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich, renounced his succession rights in 1822, making Nicholas heir to the throne.

In 1825 the Tsar gave Alexandra the Peterhof Palace, where she and Nicholas lived. It would remain her favorite summer residence.[16]

Personality[edit]

Alexandra was tall, thin, had a small head, and a pronounced brow.[18][19] She had an air of regal majesty. Her quick, light walk was graceful. She was frail, often in poor health. Her voice was hoarse, but she spoke rapidly and with decision.[20]

Alexandra Feodorovna was an avid reader and enjoyed music. Her favorite Russian writer was Lermontov.[21] She was kind and liked privacy and simplicity. She dressed elegantly, with a decided preference for light colors, and collected beautiful jewels.[18] Alexandra loved dancing and was particularly skillful at the mazurka, enjoying court balls until dawn.[22] Neither arrogant nor frivolous, Alexandra was not without intelligence and had an excellent memory; her reading was quite extensive; her judgment of men sure, slightly ironical.[23] However, she took no active interest in politics and fulfilled the role of being an empress consort, rather than being active in the public sphere.[5] She loved her family very dearly and even developed facial tics whilst fearing the Decembrist Uprising and its plans to kill her family. The facial tics were a trait that ran in the royal German-Russian-British family in many branches.

Empress of Russia[edit]

Alexandra Feodorovna became Empress consort upon her husband's accession as Tsar Nicholas I in December 1825 during a turbulent period marked by the bloody repression of the Decembrist revolt. She and her husband were consecrated and crowned at the Assumption Cathedral in the Kremlin on 3 September 1826.

Alexandra enjoyed her husband's confidence in affairs of state, but she had no interest in politics other than her personal attachment to Prussia, her native country. She was the obedient and admiring supporter of her husband's views.[18]

As empress, Alexandra Feodorovna had no interest in charity work. Her chief interests were in family affairs, balls and jewels.[18]

By 1832 Nicholas and Alexandra had seven children whom they raised with care. In 1837, when much of the Winter Palace was destroyed by fire, Nicholas reportedly told an aide-de-camp, "Let everything else burn up, only just save for me the small case of letters in my study which my wife wrote to me when she was my betrothed".[24]

Reportedly, after more than twenty-five years of fidelity, Nicholas took a mistress, Varvara Nelidova, one of Alexandra's ladies-in-waiting, after the doctors had forbidden the Empress from sexual activity due to her poor health and recurring heart-attacks. In actuality, Nicholas has at least three known illegitimate children born prior to 1842. Nicholas continued to seek refuge from the cares of state in Alexandra's company. "Happiness, joy, and repose – that is what I seek and find in my old Mouffy". he once wrote.[15] In 1845, Nicholas wept when court doctors urged the Empress to visit Palermo for several months due to poor health. "Leave me my wife",[15] he begged her physicians, and when he learned that she had no choice, he made plans to join her briefly. Nelidova went with them, and though Alexandra was jealous in the beginning, she soon came to accept the affair and remained on good terms with her husband's mistress.

Alexandra Feodorovna was always frail and in poor health. At forty, she looked far older than her years, becoming increasingly thin. For a long time, she suffered from a nervous twitching that became a convulsive shaking of her head. In 1837, she chose a resort in the Crimea for a new residence. There, Nicholas ordered that the Palace of Oreanda be built for her. She was only able to visit the palace once however; the Crimean War began in 1852. Towards the end of 1854, Alexandra Feodorovna fell ill and came close to death,[25] though she managed to recover. In 1855, Tsar Nicholas I contracted influenza, and he died on 6/18 February.

Dowager Empress and remaining years[edit]

Alexandra Feodorovna survived her husband by five years. She retired to the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo, and remained on good terms with her late husband's mistress Varvara Nelidova, whom she appointed as her personal reader.[26]

The Dowager Empress's health became more and more fragile with the years. Unable to spend the harsh winters in Russia, she was forced to make long sojourns abroad in Switzerland, Nice and Rome. She wrote in September 1859, "I am homesick for my country and I reproached myself for costing so much money at a time when Russia has need of every ruble. But I cough and my sick lungs cannot go without a southern climate".[27]

After returning from a trip abroad in July 1860, she did not cease to be ill. In the autumn of 1860, her doctors told her that she would not live through the winter if she did not travel once more to the south. Knowing the danger, she preferred to stay in St. Petersburg so that she might die on Russian soil. The night before her death, she was heard to say, "Niki, I am coming to you."[28] She died in her sleep at the age of sixty-two on 1 November 1860 at the Alexander Palace in Tsarskoe Selo.

Honours[edit]

- Kingdom of Prussia: Dame of the Order of Louise, 1st Division[29]

- Kingdom of Portugal: Dame of the Order of Queen Saint Isabel, 31 May 1850[30]

- Russian Empire: Grand Cross of St. Catherine, 13 January 1809[31]

- Kingdom of Poland: Dame of the White Eagle, 1829[32]

- Kingdom of Spain: Dame of the Order of Queen Maria Luisa, 14 May 1826[33]

Issue[edit]

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor Alexander II | 29 April 1818 | 13 March 1881 | married 1841, Princess Marie of Hesse; had issue |

| Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna | 18 August 1819 | 21 February 1876 | married 1839, Maximilian de Beauharnais, 3rd Duke of Leuchtenberg; had issue |

| Stillborn Daughter | 1820 | 1820 | |

| Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna | 11 September 1822 | 30 October 1892 | married 1846, Charles, King of Württemberg; had no issue |

| Grand Duchess Alexandra Nikolaevna | 24 June 1825 | 10 August 1844 | married 1844, Prince Frederick William of Hesse-Kassel; had issue (died in infancy) |

| Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich | 21 September 1827 | 25 January 1892 | married 1848, Princess Alexandra of Saxe-Altenburg; had issue |

| Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich | 8 August 1831 | 25 April 1891 | married 1856, Duchess Alexandra of Oldenburg; had issue |

| Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich | 25 October 1832 | 18 December 1909 | married 1857, Princess Cecilie of Baden; had issue |

Ancestry[edit]

| Ancestors of Alexandra Feodorovna (Charlotte of Prussia) |

|---|

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Barkovets & Vernovava, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, p. 8

- ^ Barkovets & Vernovava, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, p. 12

- ^ a b Barkovets & Vernovava, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, p. 15

- ^ a b Barkovets & Vernovava, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, p. 18

- ^ a b Grunwald, Tsar Nicholas I, p. 138

- ^ a b Soroka & Ruud, Becoming a Romanov , p. 32

- ^

Soroka, Marina; Ruud, Charles A. (2015). Becoming a Romanov. Grand Duchess Elena of Russia and her World (1807–1873). London: Routledge (published 2016). p. 32. ISBN 9781317175872. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

Passing through Berlin in 1814, Nicholas met the fifteen-year-old Prussian princess Charlotte that his mother and brother had picked for him as a bride [...].

- ^ a b Montefiore, The Romanovs , p. 328

- ^ Lincoln, Nicholas I Emperor and Autocrat of all the Russias, p. 66

- ^ See Feodorovna as a Romanov patronymic

- ^ Lincoln, The Romanovs, p. 414

- ^ a b Montefiore, The Romanovs , p. 329

- ^ Montefiore, The Romanovs , p. 330

- ^ Soroka & Ruud, Becoming a Romanov , p. 33

- ^ a b c Lincoln, The Romanovs, p. 418

- ^ "4 sex scandals in the Romanov family". Russia Beyond the Headlines. 8 August 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Stack's Bowers Galleries Rare Coin and Banknote Auctioneers". Stack's Bowers. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d Grunwald, Tsar Nicholas I, p. 137

- ^ Zeepvat, Romanov Autumn, p. 8

- ^ Zeepvat, Romanov Autumn, p. 10. Impressions of Alexandra Feodorovna by Lady Bloomfield, wife of the British representative in St. Petersburg

- ^ Russian documentary "Unknown Lermontov" on YouTube, Channel one

- ^ Cowles, The Romanovs, p. 167

- ^ Tsar Nicholas I The Life of an absolute monarch: Constantin de Grunwald, p. 137 Description of Alexandra Feodorovna personality by Meyendorff

- ^ Lincoln, The Romanovs, p. 417

- ^ Lincoln, The Romanovs, p. 425

- ^ Grunwald, Tsar Nicholas I, p. 289.

- ^ Letter from Alexandra Feodorovna to Meyendorff in September 1859. Grunwald, Tsar Nicholas I, p. 289.

- ^ Tsar Nicholas I The Life of an absolute monarch: Constantin de Grunwald, p. 289 quoted from a letter from Meyerdorff to his son

- ^ Decker, ed. (1821). Handbuch über den Königlich Preußischen Hof und Staat. Berlin. p. 72.

- ^ Bragança, Jose Vicente de; Estrela, Paulo Jorge (2017). "Troca de Decorações entre os Reis de Portugal e os Imperadores da Rússia" [Exchange of Decorations between the Kings of Portugal and the Emperors of Russia]. Pro Phalaris (in Portuguese). 16: 9. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Almanach de la cour: pour l'année ... 1817. l'Académie Imp. des Sciences. 1817. p. 70.

- ^ Kawalerowie i statuty Orderu Orła Białego 1705–2008 (2008), p. 289

- ^ "Real orden de Damas Nobles de la Reina Maria Luisa". Guía de forasteros en Madrid para el año de 1835 (in Spanish). En la Imprenta Nacional. 1835. p. 84.

Bibliography[edit]

- Barkovets, Olga and Vernova, Nina. Empress Alexandra Fiodorovna, Peterhof Stage Museum Preserve, Abris Art Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-5-88810-089-9.

- Cowles, Virginia. The Romanovs. Harper & Ross, 1971. ISBN 978-0-06-010908-0.

- Grunwald, Constantin de. Tsar Nicholas I the Life of An Absolute Monarch, Alcuin Press, ASIN B000I824DU.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. The Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias, Anchor, ISBN 0-385-27908-6.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. Nicholas I, Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias , Northern Illinois University Press, ISBN 0-87580-548-5.

- Montefiore, Simon Sebag. The Romanovs: 1613–1918. Deckle Edge, 2016. ISBN 978-0-307-26652-1.

- Soroka, Marina and Ruud, Charles A. Becoming a Romanov: Grand Duchess Elena of Russia and her World (1807–1873). Routledge, 2016. ISBN 978-1472457011.

- Zeepvat, Charlotte. Romanov Autumn: stories from the last century of Imperial Russia. Sutton Publishing, 2000. ISBN 9780750923378.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Alexandra Feodorovna (Charlotte of Prussia) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alexandra Feodorovna (Charlotte of Prussia) at Wikimedia Commons

- 1798 births

- 1860 deaths

- 19th-century women from the Russian Empire

- Duchesses of Holstein-Gottorp

- House of Hohenzollern

- Empresses consort of Russia

- Russian grand duchesses by marriage

- House of Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov

- Burials at Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral, Saint Petersburg

- Prussian princesses

- People from Berlin

- Dames of the Order of Saint Isabel

- Converts to Eastern Orthodoxy from Protestantism

- Daughters of kings

- Mothers of Russian emperors

- Women who experienced pregnancy loss

- Children of Frederick William III of Prussia

- Recipients of the Order of Saint Catherine

![Nicholas I; "Family Ruble" (1836) depicting the Tsar on the obverse and his family (seen here) on the reverse: Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna (center) surrounded by Alexander II as Tsarevich, Maria, Olga, Nicholas, Michael, Konstantin, and Alexandra[17]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/95/Russia_1836_1%C2%BD_Ruble.jpg/445px-Russia_1836_1%C2%BD_Ruble.jpg)