The Conservative party is Britain’s oldest and most successful political party. It has been the party of the land but also the party of the city; the party of little England and the party of empire; the party of protectionism and the party of the free market; the nasty party and the party of gay marriage; the party of Europe and the party of Brexit.

The list of its many mutations is a long one. But will the election of 2019 be the final act in reshaping the Conservative party as an English nationalist Brexit party? The pro-European strand that used to dominate the party has lost the civil war, and many of them are stepping down as MPs. Some have joined other parties. After the 2019 election there will be very few pro-European one-nation Conservatives left in the cabinet or in the parliamentary party, and many fewer women.

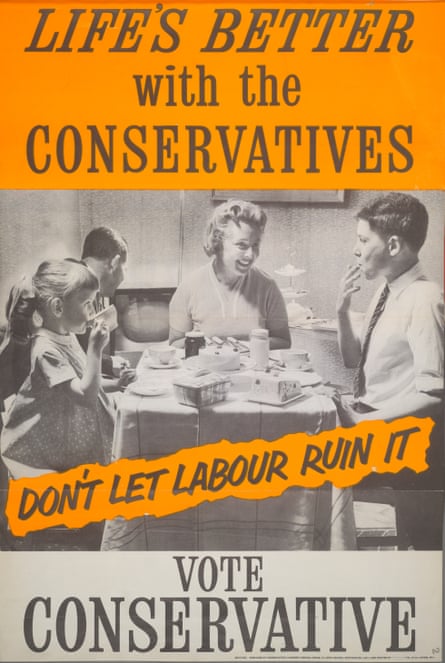

Conservatives dreaded the coming of universal suffrage and often fought against it. But in the 101 years since democracy was conceded the Conservatives have governed either alone or in coalition for two-thirds of them. To do that they have always had to draw much of their support from working-class voters.

Opponents have often wondered why the party has been so successful, in marked contrast to many other parties of the European centre-right. How has this party of property and privilege won so many elections?

Part of the answer lies in the ability of the party to reinvent itself, not to allow itself to get stuck in a ditch, always to be pragmatic and flexible. This has meant giving priority to statecraft and the pursuit of power rather than to ideology. As Trollope remarked about the 19th-century Tory party (he might have been writing about Boris Johnson): “No reform, no innovation … no revolution stinks so foully in the nostrils of an English Tory as to be absolutely irreconcilable to him. When taken in the refreshing waters of office any such pill can be swallowed.”

The classic Tory one-nation formula for government was set out by Disraeli when he said at Crystal Palace in 1872 that the three great objects of the Conservative party were to maintain the institutions of the country, to uphold the empire of England, and to elevate the condition of the people. How best to do this and build an electoral coalition sufficient to keep the Conservatives in government has always preoccupied Conservative leaders.

Now Boris Johnson has the election he wanted, he cannot afford to repeat the experience of 2017 when the Conservatives threw away their poll lead and lost their majority. Johnson needs a decisive victory to secure his leadership and crush his opponents. He dreams of governing for a decade, but this means gaining a majority for the Conservatives in excess of 50 seats. The last time the Conservatives won such a majority was in 1987, the third of Margaret Thatcher’s emphatic wins. Since 2010 the Conservatives have fought three elections, but only won an outright majority once, in 2015, and then a small one. Johnson wants to win big, and is happy taking risks and creating chaos, reshaping the Conservative party and British politics as he does so.

Johnson’s aim in this election of persuading Leave voters in northern working-class Labour seats to vote Conservative is not a new problem, even if the context created by Brexit is new. It has been what the Conservatives have always had to do. The dominant party of the 20th century was built around the pillars of union, empire, the rule of law, property and welfare. Conservatives were traditionally the party of the establishment, the crown, the aristocracy, the armed services and the police, the law, the church, the public schools, Oxford and Cambridge. They supported the empire and the union, protectionism against free trade, the gradual improvement of welfare services, and state intervention when necessary to protect citizens from hardship.

This tradition of pragmatic one-nation Conservatism was associated with Baldwin and Chamberlain in the 1930s, and then with Churchill, Eden and Macmillan in the 1950s. Edward Heath tried to continue it, but his government suffered a spectacular shipwreck and in the ensuing chaos Margaret Thatcher seized the leadership in 1975. She was responsible for another hugely significant reinvention of the Conservatives as the party of the free market, ending its interventionist and collectivist Chamberlainite tradition.

Thatcher’s legacy has been mixed for the Conservative party. She transformed its electoral and governing fortunes, allowing the Conservatives to win four elections and rule for 18 years. She broke the Labour postwar settlement that most Conservatives had come to accept, and many of its institutional bases, and set the UK political economy on a new path.

But the way she governed ultimately undermined many of the pillars that had supported Conservatism for so long, and paved the way for Labour’s longest-ever period in government, under Tony Blair. Her social background and her gender made Thatcher an outsider in the party, and even when prime minister she still thought of herself as an outsider fighting against the government and the establishment. This populist (and very un-Conservative) pose of being anti-establishment and for the people against the “elites” is one which Brexiters, including Johnson, have tried to copy, not very convincingly. It is hard to pose as an outsider when you have been educated at Eton.

In forging her new electoral coalition Thatcher lost an older one. The Conservative and Unionist party used to be able to claim that it represented all parts of the country. It won a majority of the seats and more than 50% of the vote in Scotland in 1955. It had a significant presence in all the big industrial cities, and for a long time dominated the politics of Birmingham and Liverpool. But all that has gone. Conservative support collapsed in Scotland (in 1997 the party failed to win a single seat) and also in northern cities. Thatcher bequeathed a party which had become predominantly an English party, its vote disproportionately concentrated in the south and south-east.

At the same time the party stopped being a mass-membership organisation. Those members that remain are disproportionately elderly, white and middle-class, unrepresentative either of Conservative voters or of the wider electorate, and are not being replaced by the recruitment of sufficient younger voters. At the beginning of 2019 official membership had dropped to about 120,000. This figure rose to 180,000 just before the party leadership election held last July, due largely, according to the Leave.EU co-founder Arron Banks, to the enrolment of Brexit party members, anxious to make sure a Leaver was elected.

The small size of the membership makes the party vulnerable to such entryism. When the Conservatives did have a mass membership, the members had no role in choosing the leader, something they only acquired in 2001. There are now many constituencies where there are hardly any Conservative members at all.

Since Thatcher was ousted, members have often been out of step with the party leadership, particularly on Europe. Under John Major two-thirds of the parliamentary party were pro-Europe, one third anti-Europe. In the constituencies it was the other way round. Iain Duncan Smith defeated Kenneth Clarke for the leadership in 2001 because of Clarke’s pro-European views. Boris Johnson always calculated that, as long as he could get to the membership stage of the leadership ballot, the anti-EU credentials he had honed over many years would carry him to victory. The membership has also had an increasing hand in deciding the shape of the parliamentary party by selecting anti-EU candidates.

This was one front in the civil war that has raged in the party over Europe for six decades, but which became particularly virulent in the 1990s at the time of the passage of the Maastricht treaty (founding the EU), and again under David Cameron and Theresa May.

This great schism, which now has on one side John Major, Michael Heseltine, Kenneth Clarke, Amber Rudd and Philip Hammond, and on the other Norman Tebbit, Iain Duncan Smith, John Redwood, Jacob Rees-Mogg and Priti Patel, has become unbridgeable. When he was prime minister, Major withdrew the whip from nine of the Maastricht rebels because they were making his task of governing impossible, but later relented.

Theresa May never did the same for the European Research Group rebels who refused to pass her withdrawal agreement, because of her unwillingness to split her party. Boris Johnson chose differently. In expelling 21 MPs, including two former chancellors, in September, Johnson signalled that he was happy for a formal split to take place and that only those in favour of a hard Brexit were welcome in the party.

Europe is the third great major schism in the history of the Conservative party over Britain’s place in the world. The first was in 1846, when Robert Peel repealed the Corn Laws with the support of opposition MPs. Two-thirds of his own MPs voted against him. The Conservative party lost the battle on free trade and did not form a majority government for almost 30 years.

A second great schism took place at the start of the 20th century over free trade and tariff reform. The Conservatives became the party of tariff reform, seeking to transform the far-flung British empire into a cohesive economic bloc to rival the continental empires of Germany and the United States. Conservative MPs who did not support reform were purged by their constituencies. Winston Churchill crossed the floor of the house and joined the Liberals. By 1910 there were very few supporters of free trade and liberal imperialism left in the Conservative party.

In the 1960s, with the end of empire approaching, the Conservative party pivoted to become the party of Europe. Harold Macmillan saw the pooling of sovereignty in Europe and the economic and political cooperation it made possible as the new framework that would give Britain influence, security and prosperity.

But the decision was always contested, and the opposition never entirely went away, even after Britain successfully signed the Treaty of Rome and joined the community in 1973, and after the 1975 referendum confirmed that decision with a two-to-one majority. Under Thatcher the leadership became divided over the desirability of further integration. Thatcher herself was the architect of one of the most far-reaching acts of integration, the single market, but she balked at the further stages of integration that were planned, especially the idea of a social Europe.

This ignited the civil war which is only now nearing its end. In the course of it the Conservative party has been transformed. As Duncan Smith said last week: “The Tory party is now the Brexit party.” There is no room for Remainers in its ranks. Long vilified by the Conservative press as traitors and wreckers, it is time for them to depart. Daily Telegraph columnists have been repeatedly calling for a purge, and the exodus is gathering pace.

Johnson won the referendum and then the leadership by siding firmly with the Brexiters in the party, and has reshaped the cabinet and the parliamentary party accordingly. The party risks shedding a large part of its base among moderate Conservative Remain voters, and is seeking to replace them with Labour working-class Leave voters. Johnson’s strategy is all about England. It treats the union as dispensable. The Conservative recovery in Remain-voting Scotland under Ruth Davidson is going into reverse, and Davidson has departed.

The new withdrawal agreement with the EU has been achieved by betraying the Conservatives’ DUP allies in Northern Ireland. In 1912 the Conservatives became the Conservative and Unionist party. It does not seem very appropriate any longer. Perhaps it is time for a new name: the Conservative and Brexit party.

Andrew Gamble is professor of politics at Sheffield University. His books include The Free Economy and The Strong State – the Politics of Thatcherism