Art In Conversation

Christo with Sabine Mirlesse

“We use very sturdy materials, but the fabric is always in motion. That is the incredible pleasure—extraordinary. The fabric can translate the wind. You can see the wind.”

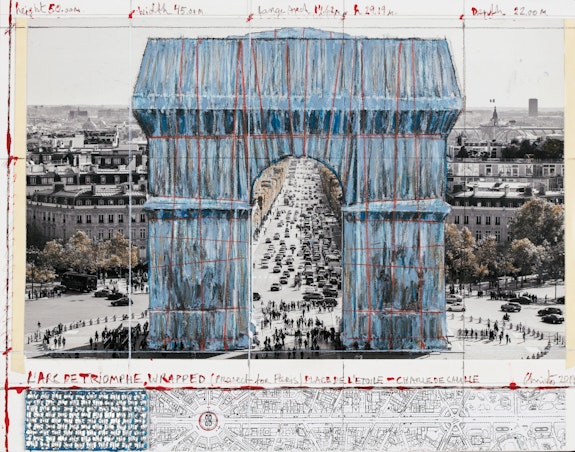

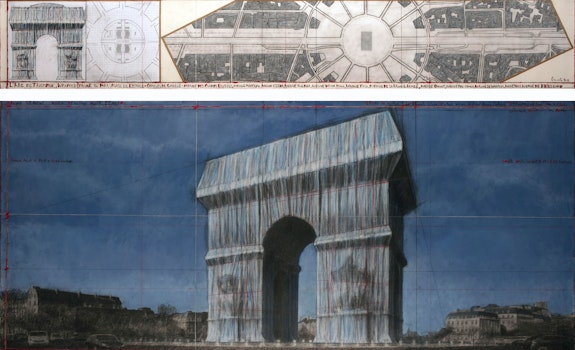

It was March 25, 2020. Christo was in “lockdown” in New York City and I found myself in “confinement” in Paris. I called landline to landline, trying to assure our connection. What I couldn’t have known was that this would be one of the artist’s last interviews. At the time, his exhibition opening had been postponed at the Pompidou because of COVID–19. Christo’s Arc de Triomphe project was still scheduled to open in the fall of 2020. It occurred to me then that the project might be postponed as well.

Weeks later I would learn of his death through a news announcement on my mobile—the strange, removed way many of us have learned of someone’s departure by now. Looking at a screen, reading, blinking and re-reading a statement, quietly and alone. A strange feeling of melancholy, shock, and gratitude sank in as soundbites of his lively voice, his strong accent, speaking declaratively into the phone, echoed through my mind.

On the occasion of Christo’s L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped at last being realized, I have revisited this conversation. It is presented here, edited for clarity and concision.

Sabine Mirlesse (Rail): So how are you? It’s a very strange situation we find ourselves in at the moment…

Christo: A world event! I’m in my studio. Working. It stopped everything, this “invisible enemy.” And of course anything can happen. The thing I never thought I’d live to see! There have been diseases like this in recent years but nothing so ferocious. I don’t really want to talk about sickness, but this is all because we are living in a much different world than before the Cold War ended. We’ve cut relations with the previous world we knew. Now everyone is traveling all the time. It wasn’t like this before the Berlin Wall fell. But you won’t remember that, you’re too young.

Rail: I was a child when the Berlin Wall came down, yes. A lot has changed just in my own lifetime, although it doesn’t compare to the changes you’ve witnessed.

Christo: This now is an enormous blessing actually, because I never have time in my studio—that is, in the past—the good old times. All the works of art we sell to pay for the installations are made by my own hand. I do not have assistants. Never. I was always involved with the preparations of the project. Now I have plenty of time to make the drawings, because there is something unusual about this wrapping of the Arc de Triomphe. It came together quite suddenly. The proposal dates back to 1962 of course, but suddenly it became possible to have the permission. I have barely one year and a half to study and prepare all of this, and to make the works to sell to make the wrapping itself. We had 10 years for the Pont Neuf. We had 25 years for the Reichstag because it was refused three times. We had 26 years waiting for the Gates as well in Central Park while it was refused and refused.

Rail: All of these years of waiting to realize each proposal. Can we talk about patience? Each project as you said takes a long time to realize if it gets the permission at all. Yet you persist over decades in certain cases and—

Christo: It is NOT patience! Jeanne–Claude always said passion! Patience is a very banal thing. Some projects stay in our hearts; some we simply lose interest in. Each project has its own story and timing.

Rail: Can we talk about the ephemeral nature of your work?

Christo: Ephemeral. I don’t like the word ephemeral, not in relation to my work. The exhibitions are temporary.

Rail: Temporary.

Christo: Ephemeral suggests something unstable. Not solid. Each of our projects are built to last. Even if they are there just for three weekends. They are built to stay forever. We cannot get permission for something to stay forever in public space. But in order to secure our permissions, they are built as though they will stay forever. Of course, there would need to be maintenance in that case and they’d need to be taken care of. But they are not ephemeral. I’ve always liked the comparison to the nomadic tribes; they build their tents, their houses, they move to the desert, but they are built very solidly because they must withstand the wind and the natural forces. They are not ephemeral shelters.

Rail: Temporary, but sturdy.

Christo: The primary material of our work is cloth—because it is very much like the tents of a nomadic tribe. They choose a location and build very solid houses. They can withstand the wind of the Sahara and of the Gobi. The cloth is the last material that is added to protect the place. That’s why our projects are more than just wrappings—that would be very simplistic! The Gates were not wrappings, The Umbrellas were not wrappings! Valley Curtain was not just wrapping. Running Fence was not just wrapping. The cloth is, yes, the principal material in our projects, but there are cables and all kinds of things. They are temporary and they are built and realized very quickly.

I come from a communist country. I decided to do something that is completely useless. Much like a painter in their studio with a white canvas. Nobody asks the painter why there is blue or black or red on his canvas. He just has the urgency to do that. So you should see the work as irrational total freedom! No justification. Now, because they are about freedom, nobody can buy them and nobody can own them. Nobody can charge tickets for this project, nobody can commercialize these projects. It’s very important that this is clear. That is why the work is unique. It can never happen again. Only one time. This is why we’ve realized 23 projects, and meanwhile have tried to get permission for 47 projects. All this to say they are not commissions.

Rail: Right—

Christo: This is freedom! The work cannot be possessed or commercialized. We go to great lengths. For example, when we were doing the Reichstag project in the middle of Berlin, we not only rented the Reichstag, but half a kilometer around the Reichstag to ensure that no company could use the space commercially during the time of the project. We even went to the superior court of Germany to stop them and succeeded. When we did The Gates, we paid three million dollars in rent to the city of New York so that nobody could film Hollywood movies or whatever in Central Park during that time. The marathon run was allowed but no commercial venture. It is all about freedom because I was living in a Soviet Bloc country, and I never believed I would get out of there. I escaped alone to do art. Simply art. My art. I feel incredible pleasure to do art.

Rail: This pandemic is a time where people do not feel free, and they do feel their own temporary-ness—their own mortality even. Your work is meant to be seen when people have the freedom to go out and enjoy it together, to leave their homes, to feel safe in public space, and in proximity to one another. You do it for the sheer pleasure you take in it, in the name of “joy” and “beauty” as you’ve said many times in television interviews, and freedom as you underline it now. Right now the whole world is in lockdown for the first time in history. A Christo work would be impossible under these circumstances. In preparing this interview it was a bit inevitable that I found myself contemplating what art can show us about freedom and public space.

Christo: I’m scared to death. I have the great chance to be alone and housed in this industrial building. I have my administrative assistant, Lorenza Giovanelli, here with me—she has her flat—there are only two of us. Lorenza is the only one equipped with a mask and gloves and everything. She goes out to get the food. We order some too. We try to be completely isolated. It’s a very science-fiction-like situation. I hope to survive, but I am not sure.

Rail: Christo! I hope that too.

Christo: Normally these projects are paid for by the works of art that I do in my studio. I have no works or material to sell for the Arc de Triomphe. I do not make drawings of projects that are being realized already. They are always done before. They often reflect the evolution of the project aesthetically, engineering-wise and so forth. We always need to do a large-scale model. The way the project will look is never decided in my studio, you see. I need a lot of time to do drawings and to make sketches and models to sell in a very short time. This is why to be isolated now, cut off from everything, gives me time to make the drawings. I love to have some fresh air, but now I’m in the studio non-stop.

Rail: A silver lining. Something useful to come from this otherwise anxious situation.

Christo: Yes! But we don’t know anything though about the future. We don’t know if the world will be closed like that for months and months. There will be no project if that’s the case or it will have to be pushed to the following year for example. The entire world is on standby. This is a terrible sickness you know, so many people my age are dying, you know.

Rail: Yes. I know. It’s awful.

Christo: What’s important to tell you is that many of these projects can be built without me.

Rail: Christo, let’s hope it doesn’t come to that.

Christo: Yes, but some projects I need to be present for—like the Wrapped Coast in Australia, or the trees in Switzerland. But this project already knows how to be built.

Rail: How did you choose the color?

Christo: The color is chosen in order to be in harmony with the great French flag. A thick blue fiber is woven into the fabric.

Rail: So it will be blue?

Christo: Very blue underneath. Yes. It’s an industrial textile, very heavy. Almost like a carpet. The fabric is woven in a criss-cross fashion with a special metallic quality achieved by a technique developed by a German company that pulverizes real aluminium and places it over the fabric. Because the fabric is woven, and the fiber is round, in the folds, you can see the blue beaming from underneath. Then there is this silver, and red. Again, it is not a solid blue, it's coming from underneath the silver, and very reflective. Sort of beaming.

Rail: Like a mirror?

Christo: Not like a mirror. More like metal. The contrast between light and shadow is very intense. And about the cloth, this Arc de Triomphe will not be a sculpture, it moves like crazy! We needed to do wind tunnel tests. The arch was built on a hill. You would never believe the wind crossing through the arches! All the time! Massive winds. It will be like a living object! Not a piece of normal architecture either. It will be moving all the time. Imagine, we are using twice as much fabric as the surface of the building itself. Think of the folds and the connecting points, the way the fabric hangs down. In some ways, we are actually enlarging the Arc de Triomphe a little bit, if you see what I’m saying. We are extending the dimensions in order to lay the fabric smoothly.

The Arc de Triomphe was a very important symbol when it was built in the 19th century. A symbol of relations between France and Germany and the rest of Europe during those tumultuous years. There is already a story about fabric being used at the Arc de Triomphe, in fact. The biggest gathering in front of the Arc de Triomphe was for the funeral of Victor Hugo. Over the Arc de Triomphe, they placed a veil of black fabric, or rather over a portion of it. You can find it online I’m sure. By the way there were also some incredible photographs made of the Nazi occupation at the Arc as well. There is really so much material regarding the history of France. I also had, by chance, a chambre de bonne overlooking the Arc de Triomphe. The Arc de Triomphe is so much in the mind of the French for the last 200 years. Every interpretation is legitimate. Not only for the Arc but for all of our projects. I cannot really spend my time collecting interpretations. It’s pointless to argue because people think what they think. You know, there was this French magazine that recently didn’t understand why I wrapped the Reichstag.

Rail: Go on…

Christo: They couldn’t fathom it—because I am not German, that I don’t speak the language, that I have nothing to do with Germany. But you know, I escaped during the Cold War. Each project is very biographical. I was stateless with no nationality. I refused my Bulgarian nationality for 17 years. I had a temporary visa in France. In the 1970s, there was at every moment the threat of the end of the world by the atomic bomb. You’re too young to know, but we were living in a very different world than today. The world was divided into East and West. All this was coming from the calamity of World War II.

Germany, which was the loser, was occupied by four Allied Forces. There were the Soviets, the British, the Americans, and the French. The capital of Germany was in the Soviet territory. But Berlin was divided in four different sections. Each winner of the war had a section of Berlin and they controlled it. Of course the Reichstag was two thirds in the section of the British, and one third in the section of the Soviets. The only place East and West met in Berlin, the only physical space, in my opinion, where the Soviet Bloc met the west, was the Reichstag. Eastern side of the Reichstag was the Soviet military sector. This is why I decided to wrap the Reichstag. Because I escaped from that terrible time in Bulgaria. Soviet country. If it wasn’t like that I would have had no reason to do the Reichstag.

Rail: It all makes perfect sense. Where East and West collide.

Christo: I’m trying to explain to you that each of these projects—there is a reason to do them. They don’t just happen like that. Some projects are urban, and others are rural. Some projects are designed for a specific place. Like The Gates in Central Park. Some pieces we need to find the places for that project. Here’s a humorous story I can tell you: in 1975 we wanted to wrap the monument of Christopher Columbus who came to America from Barcelona. We started to work on the permissions. (It was still the Cold War mind you.) After two years, the mayor of Barcelona was assassinated. Then in 1981 there was another mayor, but this time he fell sick. Finally there was a third mayor, Pasquaal Maragall, the one who brought the Olympics games to Barcelona, and he sent us a telegram in 1982 or ’83: Dear Christo and Jeanne-Claude, please come to Barcelona, I’ll give you the permission to wrap the monument for Christopher Columbus. And we replied, We don’t wanna do it anymore! My point is that each project has its own story and timing…

Rail: On that note maybe you can tell me about the story behind the Arc de Triomphe?

Christo: You know the story of it.

Rail: Of course, but I don’t know your story, Christo. There’s always a personal reason why. I’d like to know more about it. And how does it feel to be returning to Paris? So many years after living here, doing one of your first projects on Rue Visconti and then the Pont Neuf?

Christo: Of course it’s something I never believed would ever happen. That is the first point. This project’s first study was from 1962. I did several editions—multiple editions that we sold to pay for other projects even. I did a very elaborate collage edition even with fabric somewhere in the late ’80s because we considered that the Arc de Triomphe would never happen. Much like wrapping the trees on the Champs-Élysées. It was always put aside as something that would never be finished.

I’m telling you frankly, it’s weird how things happened suddenly! If it hadn’t been for that moment when Bernard Blistène, upon walking out of the Pompidou Center to go to a restaurant about two years ago, turned to me and said, “Normally when artists have a big exhibition at the museum we ask them to do something in the open around the institution.” And I turned to him and said, “Bernard, I will never do anything here! The only thing I would ever do is wrap the Arc de Triomphe!” But when I said it I didn’t ever think it would really happen.

Rail: And now its happening, or will happen in the fall if it isn’t delayed. Thanks to that conversation with Bernard. How about we take a moment to talk about water as a recurring theme in your work?

Christo: Very good question! Many people look at our projects and see water in them. The Wrapped Coast in Australia, the Running Fence in California. …Water, the fluidity of the water in contrast to the solidity of the land is present in many of our projects. There is a dynamic there. You know during the Floating Piers, some philosopher, I don’t remember who, said that there is an attraction—that we are drawn to them because we human beings are made up of 75 percent water— an enormous amount in ourselves.

Rail: So you’re saying it has to do with energy?

Christo: Well I think there is an instinctual pleasure to relate to water. I cannot explain that. It is very visible in our project thoughts, and it is not just water, but where earth and water meet. The coastline, the islands, the feet of the Pont Neuf are in the water. You know the first proposal to wrap a bridge in Paris after the Rue Visconti piece was not the Pont Neuf, actually, it was the Pont Alexandre III. It was the early 1970s. We abandoned that proposal very fast because there would be no feet of the bridge in the water in fact.

Energy is in the dynamic of the materials and their capacity to translate it. We use very sturdy materials, but the fabric is always in motion. That is the incredible pleasure—extraordinary. The fabric can translate the wind. You can see the wind. When the fabric was installed on the Running Fence and the Valley Curtain, you could see the wind. The wind is invisible. It was seen in the incredible dynamics of the fabric. The Wrapped Trees we did in Switzerland in 1999 too.

Rail: A way of making visible things that aren’t? What about permissions?

Christo: I do works of art in public space. I do not do commissions. I studied architecture, that's why I am keen to it. I have many architect friends. But I love this—how to put it—well … these two distinct periods of each of our projects. The software period and the hardware period. The software period is when the work doesn’t exist. It exists only in the mind of the people who try to help us get permission, and in the minds of people who try to stop us from getting permission.

During that time, the project develops its identity. I would be foolish to tell you that I know what the Reichstag project would look like at the start, started in ’72, 25 years before it came to be. I learned what the Pont Neuf was in the process of getting the permission. Getting the permission is the most important part of the project. It is the energy and soul of the work. I absolutely refuse to do any commission.

Rail: Understanding through the process of the making, trial and error, yes! But this official permission—it’s so specific to your work—and the way it develops through the description you plant in the minds of others that evolves on its own.

Christo: The work is revealed to us. It is rich in humanity. It is engaged. Nobody thinks of the painting of a painter before the painting is painted. Same goes for the sculpture. All our projects are discussed before they exist because they are not normal works of art. They are also architecture and urban planning.

Rail: You do get pleasure as well from the peculiarity of people arguing about an artwork that does not yet exist, no?

Christo: It’s not a pleasure. It’s just a reality. There is angst and dynamics. I remember going to art shows with Jeanne-Claude; when we went to the openings we’d always notice how nice and pleasant and civilized things were—good weather, drinks. How calm! In our stories there is a real story though. Something more.

Rail: More of an expedition rather than an exhibition perhaps?

Christo: Expedition, yes. We go through that process. But there are real things that are not cinema and not theater. Real things. Real sadness when the project is refused. Also, you don’t hire people just like that and it works. Often, you hire the wrong people and then you need to fire the wrong people. It is 100 different things.

Rail: Now I know you’ve said all interpretations are legitimate, but what about the notion of soft barriers? Whether it’s a fence or curtain or a covering…

Christo: They are not soft barriers. They are only physical interferences in the space. They are like a skin. They are not barriers. There are many senses to it. It is a disturbance in the space, Jeanne-Claude used to say, and then suddenly everyday life needs to be adjusted, to pay attention. Like walking on fabric, and then you suddenly sense something different. There are many new sensations. It’s very directly related to physical activity with how you move your body, and how you exist.

Rail: A heightening of your awareness of your body in a landscape or cityscape?

Christo: Yes.

Rail: Looking back—I know you don’t like to reflect on the past too much—

Christo: No, and I don’t like to do retrospectives. I like to do new things. I have enormous pleasure from the challenges of new projects. I cannot take my time to think about what I should have done before, this will happen after I am dead.

Rail: So then you would have nothing to tell your young Christo-self, arriving in Paris from Geneva all those decades ago, from Bulgaria, as your actual, older, Christo-self, knowing now everything you know about your life?

Christo: I cannot tell him anything. What I will say is that I had some luck when young. I was a student in the art academy and was so suffocated there by the Soviet regime. I am glad, and it was a miracle that I had the circumstances, historically, to escape. Earlier or later it probably couldn’t have happened. I escaped alone, you know. No cousins, no family, nothing.

Rail: And still, today, you would never go back to Bulgaria? Not to make work or even to visit?

Christo: I will never go back to Bulgaria. Never! I can explain to you why: all the projects are done in countries that buy my work. My first personal exhibition was in 1961 in Germany. Since that early stage, I had a large number of German collectors and institutions who wanted to buy my work. This extends as well into Belgium and Switzerland. I also had Italians buying my work. My biggest collectors are still in the United States. All the projects are contingent on whether or not the people there are interested in my works of art. This is very natural, dialectically. Marxism. Things have their natural relation with the people interested in my work.

We came to America that way. We had luck. I never studied French. I never studied English. I had no money to go to school. I was just making money to survive. I was barely selling my early works in Paris. I was so poor, I could only speak very bad French. One very good day, there were some American collectors coming to Paris in the summertime and, well, I met someone who was able to speak French, and who became very interested in my work. His name was Leo Castelli.

Rail: That is some very good luck.

Christo: Yes. And when we did Rue Visconti in Paris in 1962, Leo was also there. In 1963 Jeanne-Claude wrote to Leo that we’d like to come to America. Leo organized a room for us at the Chelsea Hotel where I made my storefront sculpture. Of course if all this had not happened I would not be in America today.

Rail: It’s just about luck?

Christo: Well, you make your own luck as well. I came here on a tourist visa for three months and then for three years lived as an illegal refugee. An illegal alien. We were living in an industrial space where you weren’t allowed to be renting for personal use. There were many steps.

Rail: Your comment about making your own luck prompts me to ask you about what you actually believe in, if anything? Destiny? Do you consider yourself a spiritual person?

Christo: Of course. I passed the border. I had a lot of fear. But also I always think I was too young to understand what would have happened. I think it was all historical circumstances. It happened. Never to be repeated again. And now I believe in my work. I am not religious. I believe in my art. Art for me is everything.