William Tuke

William Tuke and Philippe Pinel are generally credited with revolutionizing the care of the insane in England and France, respectively. These men substituted compassionate care for patients (at the York Retreat and the Bicêtre) for the typical imprisonment and harsh punishment the insane received before that time. But . . .

Before either of these men were even born, the Religious Society of Friends in Philadelphia were concerned about the sick and insane living in the new continent of America. Around 1709, they expressed this concern in one of their monthly meetings, and took steps to establish the Pennsylvania Hospital for both these groups in 1751, and later the Friends’ Asylum for the Relief of Persons Deprived of the Use of Their Reason solely for the insane in 1813. The asylum (which actually began to receive patients in 1817) had as one of its stated goals, to be a place where “the insane might see that they were regarded as men and brethren.” The York Retreat predated the Friends’ Asylum by a few years, but the idea for the American asylum had come much earlier and was probably delayed for many reasons, possibly including the political unrest going on in the colonies.

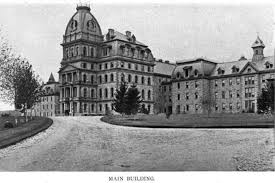

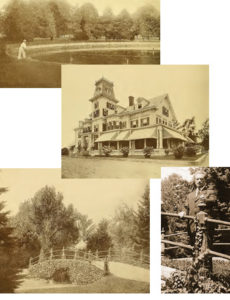

Friends’ Asylum for the Insane

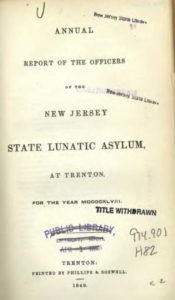

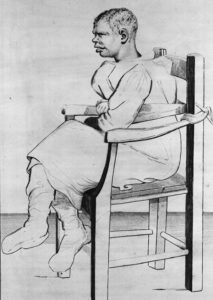

When the asylum first opened, it was only for fellow Friends, but in 1834 the religious affiliation was dropped and the institution opened its doors to all patients. From its beginning, all efforts were directed toward helping patients without resorting to restraints or cruelty. The annual report from 1853 states that “a chain was never used for the confinement of a patient.” The founders also wrote into the rules the injunction: “Come what may, the law of kindness must at all times prevail.”

Friends’ Asylum History

The Asylum was a far cry from the conditions Dorothea Dix met in Little Compton, Rhode Island (see last post), which were barbaric to the point of torture.