Shakespeare: The Animated Tales

Last updated| Shakespeare: The Animated Tales | |

|---|---|

UK DVD Box-Set | |

| Also known as |

|

| Genre | Comedy, Tragedy, History |

| Created by | Christopher Grace |

| Developed by | Leon Garfield |

| Written by | William Shakespeare |

| Creative director | Dave Edwards |

| Country of origin | United Kingdom Russia |

| Original language | English |

| No. of series | 2 |

| No. of episodes | 12 |

| Production | |

| Executive producers |

|

| Producer | Renat Zinnurov |

| Production companies | |

| Original release | |

| Network | |

| Release | 9 November 1992 – 14 December 1994 |

Shakespeare: The Animated Tales (also known as The Animated Shakespeare) is a series of twelve half-hour animated television adaptations of the plays of William Shakespeare, originally broadcast on BBC2 and S4C between 1992 and 1994.

Contents

- Development

- Creation

- Publicity

- Legacy

- Series one

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- The Tempest

- Macbeth

- Romeo and Juliet

- Hamlet

- Twelfth Night

- Series two

- Richard III

- The Taming of the Shrew

- As You Like It

- Julius Caesar

- The Winter's Tale

- Othello

- See also

- References

- External links

The series was commissioned by the Welsh language channel S4C. Production was co-ordinated by the Dave Edwards Studio in Cardiff, although the shows were animated in Moscow by Soyuzmultfilm, using a variety of animation techniques. The scripts for each episode were written by Leon Garfield, who produced heavily truncated versions of each play. The academic consultant for the series was Professor Stanley Wells. The dialogue was recorded at the facilities of BBC Wales in Cardiff.

The show was both a commercial and a critical success. The first series episode "Hamlet" won two awards for "Outstanding Individual Achievement in Animation" (one for the animators and one for the designers and director) at the 1993 Emmys, and a Gold Award at the 1993 New York Festival. The second-season episode "The Winter's Tale" also won the "Outstanding Individual Achievement in Animation" at the 1996 Emmys. The episodes continue to be used in schools as teaching aids, especially when introducing children to Shakespeare for the first time. However, the series has been critiqued for the large number of scenes cut to make the episodes shorter in length. [1]

In the United States, the series aired on HBO and featured live-action introductions by Robin Williams. [2]

Development

Creation

The series was conceived in 1989 by Christopher Grace, head of animation at S4C. Grace had previously worked with Soyuzmultfilm on an animated version of the Welsh folktale cycle, the Mabinogion , and he turned to them again for the Shakespeare project, feeling "if we were going to animate Shakespeare in a thirty-minute format, then we had to go to a country that we knew creatively and artistically could actually deliver. And in my view, frankly, there was only one country that could do it in the style that we wanted, that came at it from a different angle, a country to whom Shakespeare is as important as it is to our own." [3] Grace was also very keen to avoid creating anything Disney-esque; "Disney has conditioned a mass audience to expect sentimentality; big, gooey-eyed creatures with long lashes, and winsome, simpering female characters. This style went with enormous flair and verve and comic panache; but a lot of it was kitsch." [4]

The series was constructed by recording the scripts before any animation had been done. Actors were hired to recite abbreviated versions of the plays written by Leon Garfield, who had written a series of prose adaptations of Shakespeare's plays for children in 1985, Shakespeare Stories. According to Garfield, editing the plays down to thirty minutes whilst maintaining original Shakespearean dialogue was not easy; "lines that are selected have to carry the weight of narrative, and that's not always easy. It frequently meant using half a line, and then skipping perhaps twenty lines, and then finding something that would sustain the rhythm but at the same time carry on the story. The most difficult by far were the comedies. In the tragedies, you have a very strong story going straight through, sustained by the protagonist. In the comedies, the structure is much more complex." [3] Garfield compared the task of trying to rewrite the plays as half-hour pieces as akin to "painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel on a postage stamp." [5] To maintain narrative integrity, Garfield added non-Shakespearean voice-over narration to each episode, which would usually introduce the episode and then fill in any plot points skipped over by the dialogue. [6] The use of a narrator was also employed by Charles Lamb and Mary Lamb in their own prose versions of Shakespeare's plays for children, Tales from Shakespeare , published in 1807, to which Garfield's work is often compared. [7] However, fidelity to the original texts was paramount in the minds of the creators as the episodes sought "to educate their audience into an appreciation and love of Shakespeare, out of a conviction of Shakespeare as a cultural artifact available to all, not restricted to a narrowly defined form of performance. Screened in dozens of countries, The Animated Tales is Shakespeare as cultural educational television available to all." [8]

The dialogue was recorded at the sound studios of BBC Wales in Cardiff. During the recording, Garfield himself was present, as was literary advisor, Stanley Wells, as well as the Russian directors. All gave input to the actors during the recording sessions. The animators then took the voice recordings back to Moscow and began to animate them. [3] At this stage, the project was overseen by Dave Edwards, who co-ordinated the Moscow animation with S4C. Edwards' job was to keep one eye on the creative aspects of the productions and one eye on the financial and practical aspects. This didn't make him especially popular with some of the directors, but his role was an essential one if the series was to be completed on time and under budget. According to Elizabeth Babakhina, executive producer of the series in Moscow, the strict rules brought into play by Edwards actually helped the directors; "Maybe at long last our directors will learn that you can't break deadlines. In the past, directors thought "If I make a good film, people will forgive me anything." Now they've begun to understand that they won't necessarily be forgiven even if they make a great film. It has to be a great film, and be on time." [3]

Publicity

There was considerable media publicity prior to the initial broadcast of the first season, with the then Prince Charles commenting "I welcome this pioneering project which will bring Shakespeare's great wisdom, insight and all-encompassing view of mankind to many millions from all parts of the globe, who have never been in his company before." [9] An article in the Radio Times wrote "as a result of pre-sales alone, tens of millions of people are guaranteed to see it and Shakespeare is guaranteed for his best year since the First Folio was published in 1623." [10] One commentator who was distinctly unimpressed with the adaptations, however, was scholar and lecturer Terence Hawkes who wrote of the episodes, "they will be of no use. They are packages of stories based on the Shakespearean plots, which themselves were not original. So they aren't going to provide much insight into Shakespeare." [11]

The second season aired two years after the first, and received considerably less media attention. [12]

Legacy

A major part of the project was the educational aspect of the series, especially the notion of introducing children to Shakespeare for the first time. The series was made available to schools along with a printed copy of the script for each episode, complete with illustrations based on, but not verbatim copies of, the Russian animation. The printed scripts were slightly longer than Garfield's final filmed versions, but remained heavily truncated. [4] Each text also came with a study guide for teachers. [13] The Animated Tales have gone on to become "one of the most widely used didactic tools in British primary and secondary schools." [14]

In 1996, the producers created a follow-up series, Testament: The Bible in Animation . [15]

In 2000, Christopher Grace launched the Shakespeare Schools Festival (SSF) using Leon Garfield's twelve abridged scripts. The festival takes place annually, with hundreds of school children performing half-hour shows in professional theatres across the UK. [16]

Series one

A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Directed and designed by Robert Saakiants

- Originally aired: 9 November 1992

- Animation type: Cel animation

- Menna Trussler as Narrator

- Daniel Massey as Oberon

- Suzanne Bertish as Titania

- Anthony Jackson as Puck

- Abigail McKern as Hermia

- Kathryn Pogson as Helena

- Charles Millham as Demetrius

- Kim Wall as Lysander

- Bernard Hill as Bottom

- Peter Postlethwaite as Quince

- Anna Linstrum as Fairy

- Lorraine Cole as Fairy

The Tempest

- Directed by Stanislav Sokolov

- Designed by Elena Livanova

- Originally aired: 16 November 1992

- Animation type: Stop motion puppet animation

- Martin Jarvis as Narrator

- Timothy West as Prospero

- Alun Armstrong as Caliban

- Ella Mood as Ariel

- Katy Behean as Miranda

- Jonathan Tafler as Ferdinand

- John Moffatt as Alonzo

- James Greene as Gonzalo

- Sion Probert as Sebastian

- Peter Guinness as Antonio

- Stephen Thorne as Stephano

- Ric Jerrom as Trinculo

Macbeth

- Directed by Nikolai Serebryakov

- Designed by Vladimir Morozov and Ildar Urmanche

- Originally aired: 23 November 1992

- Animation type: Cel animation

- Alec McCowen as Narrator

- Brian Cox as Macbeth

- Zoë Wanamaker as Lady Macbeth

- Laurence Payne as Duncan

- Patrick Brennan as Banquo

- Clive Merrison as Macduff

- Mary Wimbush as Witch

- Val Lorraine as Witch

- Emma Gregory as Witch

- Richard Pearce as Donalbain

- David Acton as Malcolm

- John Baddeley as Lennox

Romeo and Juliet

- Directed by Efim Gamburg

- Designed by Igor Makarov

- Originally aired: 30 November 1992

- Animation type: Cel animation

- Felicity Kendal as Narrator

- Linus Roache as Romeo

- Clare Holman as Juliet

- Jonathan Cullen as Benvolio

- Greg Hicks as Mercutio

- Brenda Bruce as Nurse

- Garard Green as Friar Laurence

- Brendan Charleson as Tybalt

- Charles Kay as Capulet

- Maggie Steed as Lady Capulet

Hamlet

- Directed by Natalya Orlova

- Designed by Peter Kotov and Natalia Demidova

- Originally aired: 7 December 1992

- Animation type: Paint on glass

- Michael Kitchen as Narrator

- Nicholas Farrell as Hamlet

- John Shrapnel as Claudius and The Ghost

- Susan Fleetwood as Gertrude

- Tilda Swinton as Ophelia

- John Warner as Polonius

- Dorien Thomas as Horatio

- Andrew Wincott as Laertes

Twelfth Night

- Directed by Maria Muat

- Designed by Ksenia Prytkova

- Originally aired: 14 December 1992

- Animation type: Stop motion puppet animation

- Rosemary Leach as Narrator

- Fiona Shaw as Viola

- Roger Allam as Duke Orsino

- Suzanne Burden as Olivia

- Gerald James as Malvolio

- William Rushton as Toby Belch

- Stephen Tompkinson as Sir Andrew

- Alice Arnold as Maria

- Stefan Bednarczyk as Feste

- Hugh Grant as Sebastian

Series two

Richard III

- Directed by Natalya Orlova

- Designed by Peter Kotov

- Originally aired: 2 November 1994

- Animation type: Paint on glass

- Antony Sher as Richard

- Alec McCowen as Narrator

- Eleanor Bron as Duchess of York

- Tom Wilkinson as Buckingham

- James Grout as Catesby/Ely

- Sorcha Cusack as Queen Elizabeth

- Suzanne Burden as Anne

- Stephen Thorne as Hastings/Cardinal

- Michael Maloney as Clarence/Norfolk

- Spike Hood as Prince Edward

- Hywel Nelson as Duke of York

- Patrick Brennan as Richmond/2nd Murderer

- Philip Bond as Tyrrel

- Brendan Charleson as 1st Murderer/Messenger

The Taming of the Shrew

- Directed by Aida Ziablikova

- Designed by Olga Titova

- Originally aired: 9 November 1994

- Animation type: Stop motion puppet animation

- Amanda Root as Kate

- Nigel Le Vaillant as Petruchio

- Malcolm Storry as Sly/Nathaniel

- Manon Edwards as Bianca

- John Warner as Gremio/Servant/Tailor

- Gerald James as Baptista

- Lawmary Champion as Hostess/Widow

- Hilton McRae as Hortensio/Peter

- Richard Pearce as Lucentio

- Big Mick as Narrator

As You Like It

- Directed by Alexei Karayev

- Designed by Valentin Olshvang

- Originally aired: 16 November 1994

- Animation type: Paint on glass (using watercolors) [17]

- Sylvestra Le Touzel as Rosalind

- Maria Miles as Celia/Audrey

- John McAndrew as Orlando

- Peter Gunn as Touchstone/Messenger

- David Holt as Silvius/Hymen

- Nathaniel Parker as Jacques/Oliver

- Stefan Bernarczyk as Amiens/Lord

- Christopher Benjamin as Duke Frederick/Corin

- Garard Green as Duke Senior/Adam

- Eiry Thomas as Phoebe

- David Burke as Narrator

Julius Caesar

- Directed by Yuri Kulakov

- Designed by Galina Melko and Victor Chuguyevsky

- Originally aired: 30 November 1994

- Animation type: Cel animation

- Joss Ackland as Caesar

- Frances Tomelty as Calphurnia

- David Robb as Brutus

- Hugh Quarshie as Cassius

- Jim Carter as Mark Antony

- Judith Sharp as Portia

- Peter Woodthorpe as Casca

- Andrew Wincott as Narrator/Octavius

- Dillwyn Owen as Soothsayer/Trebonius

- Tony Leader as Cinna/Decius

- John Miers as Lucius

The Winter's Tale

- Directed by Stanislav Sokolov

- Designed by Helena Livanova

- Originally aired: 7 December 1994

- Animation type: Stop motion puppet animation

- Anton Lesser as Leontes

- Jenny Agutter as Hermione

- Sally Dexter as Paulina

- Michael Kitchen as Polixenes

- Adrienne O'Sullivan as Perdita

- Stephen Tompkinson as Autolycus

- Philip Voss as Shepherd/Judge

- Simon Harris as Shepherd's Son/Servant

- Jonathan Tafler as Camillo

- Timothy Bateson as Antigonus

- Jonathan Firth as Florizel

- Spike Hood as Shepherd's Young Son

- Hywel Nelson as Mamillius

- Roger Allam as Narrator

Othello

- Directed and designed by Nikolai Serebryakov

- Originally aired: 14 December 1994

- Animation type: Cel animation

- Colin McFarlane as Othello

- Gerard McSorley as Iago

- Philip Franks as Cassio

- Sian Thomas as Desdemona

- Dinah Stabb as Emilia/Bianca

- Terry Dauncey as Brabantio

- Ivor Roberts as Duke/Lodovico

- Simon Ludders as Roderigo

- Philip Bond as Narrator

See also

- An Age of Kings (1960)

- The Spread of the Eagle (1963)

- The Wars of the Roses (1963; 1965)

- BBC Television Shakespeare (1978–1985)

- ShakespeaRe-Told (2005)

- The Hollow Crown (2012; 2016)

Related Research Articles

Animation is a filmmaking technique by which still images are manipulated to create moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent celluloid sheets (cels) to be photographed and exhibited on film. Animation has been recognized as an artistic medium, specifically within the entertainment industry. Many animations are computer animations made with computer-generated imagery (CGI). Stop motion animation, in particular claymation, has continued to exist alongside these other forms.

While the history of animation began much earlier, this article is concerned with the development of the medium after the emergence of celluloid film in 1888, as produced for theatrical screenings, television and (non-interactive) home entertainment.

The Goofy Gophers are animated cartoon characters in Warner Bros.' Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series of cartoons. The gophers are small and brown with tan bellies and buck teeth. They both have British accents. Unnamed in the theatrical cartoons, they were given the names Mac and Tosh in the 1960s TV show The Bugs Bunny Show. The names are a pun on the surname "Macintosh". They are characterized by an abnormally high level of politeness.

Claymation, sometimes called clay animation or plasticine animation, is one of many forms of stop-motion animation. Each animated piece, either character or background, is "deformable"—made of a malleable substance, usually plasticine clay.

Traditional animation is an animation technique in which each frame is drawn by hand. The technique was the dominant form of animation in cinema until the end of the 20th century, when there was a shift to computer animation in the industry, specifically 3D computer animation.

Cel shading or toon shading is a type of non-photorealistic rendering designed to make 3-D computer graphics appear to be flat by using less shading color instead of a shade gradient or tints and shades. A cel shader is often used to mimic the style of a comic book or cartoon and/or give the render a characteristic paper-like texture. There are similar techniques that can make an image look like a sketch, an oil painting or an ink painting. The name comes from cels, clear sheets of acetate which were painted on for use in traditional 2D animation.

The history of Russian animation is the visual art form produced by Russian animation makers. As most of Russia's production of animation for cinema and television were created during Soviet times, it may also be referred to some extent as the history of Soviet animation. It remains a nearly unexplored field in film theory and history outside Russia.

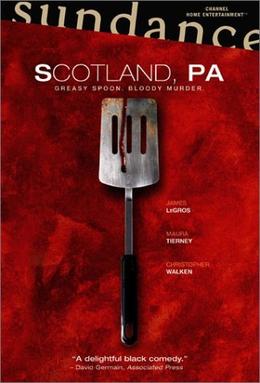

Scotland, PA is a 2001 American black comedy crime film written and directed by Billy Morrissette as a modernized retelling of Macbeth. The film stars James LeGros, Maura Tierney, and Christopher Walken. The Shakespearean tragedy, originally set in Dunsinane Castle in 11th-century Scotland, is reworked into a dark comedy set in 1975, centered on "Duncan's Cafe", a fast-food restaurant in the small town of Scotland, Pennsylvania. The film was shot in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Stanislav Mihaylovich Sokolov is a Russian stop-motion animation director. He graduated from VGIK in 1971 and has since then worked with Studios Soyuzmultfilm, DEFA, Christmasfilms and S4C. He was awarded a number of prizes for his films, most notably an Emmy in 1992 for his contribution to The Animated Shakespeare series. Sokolov is teaching at VGIK, where he is Professor for Animation and Computer Graphics.

Clay painting animation is a form of clay animation, which is one of the many kinds of stop motion animation. It blurs the distinction between clay animation, cel animation and cutout animation.

Richard Loncraine is a British film and television director.

Testament: The Bible in Animation is a 1996 Welsh-Russian Christian animated series that was produced by and shown on Sianel 4 Cymru (S4C). It was also shown on the BBC. It featured animated versions of stories from the Bible, each story using its own unique style of animation, including stop-motion animation. It ran for one series of nine episodes in the United Kingdom and won one Emmy, with three nominations, in the United States. It includes the song "Adiemus" as its intro.

Storybook World is an animated anthology series released on VHS. The show was produced by A.J Shalleck under Fox Lorber and distributed by Kids Klassics. Each episode is an animated retelling of classic children's stories narrated by Fred Newman.

Little Women, also known as Little Women's Four Sisters or From "Little Women Story": Little Women's Four Sisters, is a 1981 Japanese animated television series adaptation of Louisa May Alcott's 1868-69 two-volume novel Little Women. The series is directed by Kazuya Miyazaki and produced by Toei Animation for the Kokusai Eiga-sha company.

Over fifty films of William Shakespeare's Hamlet have been made since 1900. Seven post-war Hamlet films have had a theatrical release: Laurence Olivier's Hamlet of 1948; Grigori Kozintsev's 1964 Russian adaptation; a film of the John Gielgud-directed 1964 Broadway production, Richard Burton's Hamlet, which played limited engagements that same year; Tony Richardson's 1969 version featuring Nicol Williamson as Hamlet and Anthony Hopkins as Claudius; Franco Zeffirelli's 1990 version starring Mel Gibson; Kenneth Branagh's full-text 1996 version; and Michael Almereyda's 2000 modernisation, starring Ethan Hawke.

Calon is the trading name of Mount Stuart Media Ltd., a British animation television production company based in Cardiff, the capital of Wales, which primarily produced animation series in Welsh for S4C. The company was formerly known as Siriol Animation and Siriol Productions.

King Lear is a 1953 live television adaptation of the Shakespeare play staged by Peter Brook and starring Orson Welles. Preserved on kinescope, it aired October 18, 1953, as part of the CBS television series Omnibus, hosted by Alistair Cooke. The cast includes Micheál Mac Liammóir and Alan Badel.

There have been numerous on screen adaptations of Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew. The best known cinematic adaptations are Sam Taylor's 1929 The Taming of the Shrew and Franco Zeffirelli's 1967 The Taming of the Shrew, both of which starred the most famous celebrity couples of their era; Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks in 1929 and Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in 1967. On television, perhaps the most significant adaptation is the 1980 BBC Television Shakespeare version, directed by Jonathan Miller and starring John Cleese and Sarah Badel.

References

- ↑ Semenza, Gregory M. Colón (17 July 2008). "Teens, Shakespeare, and the Dumbing Down Cliché: The Case of The Animated Tales". Shakespeare Bulletin. 26 (2): 37–68. doi:10.1353/shb.0.0006. ISSN 1931-1427. S2CID 191466217.

- ↑ Erickson, Hal (2005). Television Cartoon Shows: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, 1949 Through 2003 (2nd ed.). McFarland & Co. pp. 730–731. ISBN 978-1476665993.

- 1 2 3 4 Animating Shakespeare (DVD Documentary). Wales: BBC Wales. 1992.

- 1 2 Osborne, Laurie E. (1997). "Poetry in Motion: Animating Shakespeare". In Boose, Lynda E.; Burt, Richard (eds.). Shakespeare, The Movie: Popularizing the Plays on Film, TV and Video . London: Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-0415165853.

- ↑ Waite, Teresa (9 November 1992). "Tempest and others the size of a teapot". The New York Times . p. C16.

- ↑ Osborne, Laurie E. (1997). "Poetry in Motion: Animating Shakespeare". In Boose, Lynda E.; Burt, Richard (eds.). Shakespeare, The Movie: Popularizing the Plays on Film, TV and Video . London: Routledge. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0415165853.

- ↑ Pennacchia, Maddalena (2013). "Shakespeare for Beginners: The Animated Tales from Shakespeare and the Case Study of "Julius Caesar"". In Müller, Anja (ed.). Adapting Canonical Texts in Children's Literature. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-1472578884.

- ↑ Holland, Peter (2007). "Shakespeare abbreviated". In Shaughnessy, Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare and Popular Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0521605809.

- ↑ Quoted in Osborne, Laurie E. (1997). "Poetry in Motion: Animating Shakespeare". In Boose, Lynda E.; Burt, Richard (eds.). Shakespeare, The Movie: Popularizing the Plays on Film, TV and Video . London: Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 978-0415165853.

- ↑ "Macbeth Moscow Style". Radio Times . 7 November 1992. p. 29.

- ↑ Quoted in Osborne, Laurie E. (2003). "Mixing Media and Animating Shakespeare". In Burt, Richard; Boose, Lynda E. (eds.). Shakespeare, The Movie II: Popularizing the Plays on Film, TV, Video, and DVD. London: Routledge. p. 144. ISBN 978-0415282994.

- ↑ Osborne, Laurie E. (2003). "Mixing Media and Animating Shakespeare". In Burt, Richard; Boose, Lynda E. (eds.). Shakespeare, The Movie II: Popularizing the Plays on Film, TV, Video, and DVD. London: Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 978-0415282994.

- ↑ Osborne, Laurie E. (1997). "Poetry in Motion: Animating Shakespeare". In Boose, Lynda E.; Burt, Richard (eds.). Shakespeare, The Movie: Popularizing the Plays on Film, TV and Video . London: Routledge. p. 109. ISBN 978-0415165853.

- ↑ Pennacchia, Maddalena (2013). "Shakespeare for Beginners: The Animated Tales from Shakespeare and the Case Study of "Julius Caesar"". In Müller, Anja (ed.). Adapting Canonical Texts in Children's Literature. London: Bloomsbury. p. 60. ISBN 978-1472578884.

- ↑ Erickson, Hal (2005). Television Cartoon Shows: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, 1949 Through 2003 (2nd ed.). McFarland & Co. p. 842. ISBN 978-1476665993.

- ↑ Pennacchia, Maddalena (2013). "Shakespeare for Beginners: The Animated Tales from Shakespeare and the Case Study of "Julius Caesar"". In Müller, Anja (ed.). Adapting Canonical Texts in Children's Literature. London: Bloomsbury. p. 67. ISBN 978-1472578884.

- ↑ Osborne, Laurie E. (2003). "Mixing Media and Animating Shakespeare". In Burt, Richard; Boose, Lynda E. (eds.). Shakespeare, The Movie II: Popularizing the Plays on Film, TV, Video, and DVD. London: Routledge. p. 148. ISBN 978-0415282994.

External links

Text is available under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.